1:00 pm EDT - 2:30 pm EDT

Past Event

1:00 pm - 2:30 pm EDT

Washington, DC

On Wednesday May 21, the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World at the Brookings Institution hosted a book launch for Michael Cook’s recently published Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective. After outlining the argument of the book, Cook discussed some key issues with Michael Doran and responded to questions from the audience. What follows summarizes the main points considered in the discussion.

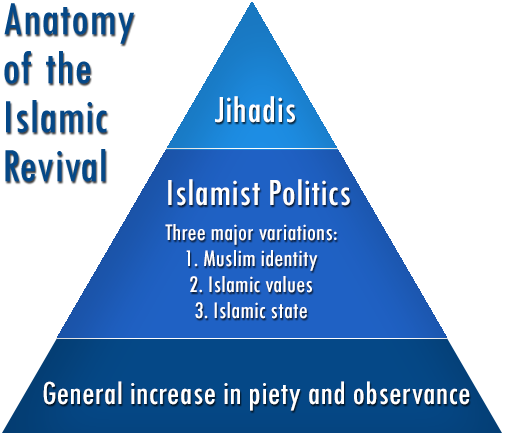

The starting-point of the book is the fact that Islam is more salient in modern politics than any other major religion. While each element within the Islamic revival of the last few decades—the rise in piety and observance, the politics of Muslim identity, the politics of Muslim values, the politics of the Muslim state, and the legitimation of violence as a religious duty—can be paralleled in some other religion, the fact is that the combination is unique to the Islamic case.

Why should Islam be so politically salient? In a world in which the West is the outlier at one end of the spectrum, why should it be the Islamic world that is the outlier at the other end?

The book is a sustained attempt to answer this question by looking successively at the capacity of Islam to shape political identity, its ability to provide its adherents with values that are attractive in modern political contexts, and the readiness with which it can be restated in a fundamentalist vein.

With regard to identity, Cook argued that Islam provides its adherents with an identity that is at least potentially political: it was closely associated with membership of a polity during the rise of Islam, and this association can readily be invoked in modern times. He contrasted this with the way Hindu identity politics are wrong-footed by the absence from the tradition of a concept of Hindu identity, and by the way the caste system renders much of the population indifferent or hostile to political appeals to such an identity.

With regard to values, he stressed the fact that some of the values associated with the early Islamic polity play very well in the modern world—the relative egalitarianism that marks early Islamic society, for example, and its rejection of despotism and patrimonialism. These are values that resonate in the modern world in a way that the hierarchic social values and exclusively monarchic political values of the Hindu tradition do not.

With regard to fundamentalism, he emphasized the way in which going back to the roots of the tradition can highlight values that are in tune with those of modern times—more so than the values of the later Islamic tradition, or those enshrined in the earliest texts of other religions.

Cook made it clear that he was not saying that Muslims are constrained by their tradition to construct their politics out of their religion; indeed much of the politics of the modern Muslim world has been conducted under the aegis of non-religious values, variously liberal, leftist, fascist, and above all nationalist. Nor was he saying that a commitment to construct one’s political values out of one’s religion commits one to any specific kind of Islamist politics: Islamism comes in very different flavors. What he was saying is that the Muslim heritage provides its adherents with options for constructing their politics that followers of other religions may not have.

Suzanne Maloney

February 24, 2026

Ithiel Batumike, Fred Bauma, Jason Stearns

November 4, 2025

Sharan Grewal

April 2, 2025