Talk of the Arab Spring has turned, in some quarters, to talk of an Arab Winter. The latest cause for pessimism has been the results of the first of three rounds of Egyptian parliamentary elections, where the Muslim Brotherhood and a Salafist political party garnered, respectively, roughly 49% and 20% of the available seats, making it likely they will dominate the next parliament.

As I wrote in the chapter “Democratization 101” in The Arab Awakening: America and the Transformation of the Middle East, we know from experience elsewhere in the world that democratic transitions are long and complicated processes. Toppling a dictatorship is in many respects the easy part; building a new democratic state in its place is a much more complicated affair. Egypt’s transition comes with no guarantees that it will lead, in the end, to democracy. There are bound to be setbacks and surprises along the way. Regime insiders and non-democratic groups will look for opportunities to try to co-opt the revolution for their own purposes.

We also always knew that the Muslim Brotherhood would perform well in these elections. The Brotherhood and the Salafis have long been better organized and better resourced than their liberal counterparts, in part because the Mubarak government found it more difficult to crack down on religious groups. It is one of the reasons that successive U.S. administrations at times hesitated in pushing too hard for democracy. Success in democratic politics often boils down to organization—how many voters can you get to the polls—and here the Islamists had a significant head start.

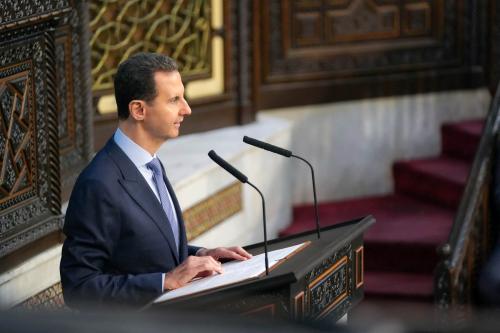

Before giving in to pessimism, it is important to recall all that has changed over the past year. Last November, Hosni Mubarak’s regime was conducting parliamentary elections that were as fraudulent as they come, in which his New Democratic Party secured 209 of the 211 seats in parliament; this year’s have been remarkably free and fair by comparison, even if we may not like the results. Now Mubarak is on trial and his NDP has been consigned to the dustbin of history. Elsewhere, Tunisians have sent former president Ben Ali into exile and held successful elections of their own; Libyans have dispensed with Muammar Qaddafi; Yemenis seem finally to be edging Ali Abdullah Saleh from power; and Syria’s Bashar Assad is internationally isolated and on the defensive. In the one region of the world that seemed immune to the democratic winds of change—the Arab world—that change is now sweeping through at a breathtaking pace.

In The Arab Awakening, I discuss the uncertainties associated with democratic transitions but argue that the best guarantor of success over the long-term will be the emergence of a political constituency for democracy. Well-designed laws and institutions are important, but they will only work as intended if the public is prepared to defend them. Politicians need to know that their own citizens will make them pay a price should they deviate from the new rules of the game.

In this regard, right before Egyptians went to the polls, a drama of great import played out in Tahrir Square. Angered by the military’s killing of scores of protestors, more than a hundred thousand Egyptians flooded back into the square demanding that the military speed the transition to civilian rule. In response, the interim government resigned and the military moved up the date for presidential elections and the transfer of governing authority to civilians.

These developments were quickly overshadowed by the liberals’ poor showing in the elections. If Egypt’s new generation of youth could not win the ultimate test of elections, what use were they? Indeed, much of the Egyptian public has tired of the protestors, as perhaps have we. What seemed so remarkable a year ago—ordinary Arabs taking to the streets to demand their rights—now seems commonplace. Many Egyptians have had enough of protestors littering their streets, just as we’ve grown indifferent to the scenes of protests flooding our television screens every night. We’re not just weary but wary — concerned that mass protests will degenerate into chaos or mob rule.

But at a time when political institutions are weak or unformed, continued public demonstrations of citizens’ desire for democracy remain vital. The elections may be determining who will serve in the next parliament, but the demonstrators in the streets are shaping how much power that parliament will actually wield.

Three forces now seem to be vying to determine Egypt’s future: 1) the military, which seems intent above all on protecting its own privileges; 2) the Islamists, who are likely to emerge as a governing bloc, but remain conflicted internally over their commitment to democracy and the role that religion should play in public life; and 3) the youth of Tahrir Square. Despite liberals’ poor showing at the polls, the latter still have a critical role to play, ensuring one form of tyranny does not simply replace another. Until democratic institutions fully take root in Egypt, their help will continue to be needed to ensure that the military moves forward with the promised transition to democracy, the new parliament plays by the democratic rules of the game, and minority rights are respected.

An empowered and engaged citizenry remains critical to preserving the fruits of this Arab Spring.

Commentary

The Long Spring Ahead

December 8, 2011