Reducing the U.S. budget deficit takes center stage as Congress reconvenes and two outside commissions develop recommendations for action. Brookings experts Bill Frenzel, Isabel Sawhill, William Galston, William Gale, Jonathan Rauch and Henry Aaron analyze the challenges and tradeoffs, and offer their own advice on this crucial issue.

Three Cheers for Bowles and Simpson

Bill Frenzel, Guest Scholar, Economic Studies

The fiscal disorder of the U.S. government has long been a matter of public knowledge. Unfortunately, it has been viewed as a long-term problem. Policymakers, and their constituents, have notoriously short horizons.

Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) had been the only person to produce a possible solution in his now famous “Road Map.” It attracted plenty of criticism but, until now, no other prominent person or group has developed an alternative plan.

On Thursday, Nov. 10, another well-detailed plan was announced. Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, revealed their Chairmen’s Mark, the first complete alternative to Ryan’s road map. Whether the full commission will approve that plan, or one like it, is not yet known.

Meanwhile, the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Domenici-Rivlin Commission is working on a plan similar to Bowles-Simpson and will report this month. Suddenly the budget world will be awash in comprehensive plans to reduce deficits and stabilize the debt.

Policymakers may squirm, but they can no longer escape the fact that prompt action requiring universal sacrifice is necessary. The Bowles-Simpson plan starkly illustrates that formerly-sacred cows will have to be slaughtered in wholesale quantities.

Small adjustments won’t do the job. All categories of spending, and revenues, will be included in the sacrifice. Defense spending will not be immune, nor will entitlements, nor tax expenditures, nor other revenues. There will be sharp debate and negotiation about how much gets done to whom, but the problem is so big that nearly everyone will pay a part of the price.

Three cheers for Bowles and Simpson! They are showing America what needs to be done. They, the earlier pioneer, Ryan, and those to follow—like Rivlin and Domenici—deserve some special “Hero of the Republic” Award. Instead, like all bearers of unhappy news, they will get heaps of scorn and abuse.

However, we have good reason to follow their wise counsel. If we don’t, America may not quite become Greece, but it is likely to lose control of its own destiny.

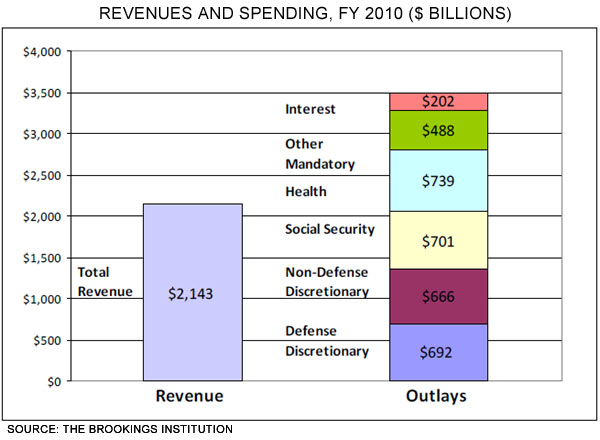

<not-mobile message=”** To view the chart, please visit brookings-edu-2023.go-vip.net on your desktop **”>The figure below breaks down the $3.5 trillion federal budget into its main categories. The chart is adapted from “The Future Is Now: A Balanced Plan to Stabilize Public Debt and Promote Economic Growth,” a paper by William Galston and Maya MacGuineas.

</not-mobile>

</not-mobile>

Bowles-Simpson Leads the Way to Reducing the Deficit

Isabel V. Sawhill, Senior Fellow and Director, Budgeting for National Priorities

The co-chairs of the president’s fiscal commission have put forward a strong and interesting set of proposals (pdf) to reduce an absolutely frightening accumulation of debt over the next decade and beyond. The plan includes many positive elements, in my view: a focus on “cutting but investing” in education, infrastructure and research; a sensitivity to raising revenues and cutting benefits in a way that protects the less advantaged and asks the wealthy to sacrifice more; a willingness to tackle many sacred cows from agricultural subsidies to the mortgage interest deduction; and a bold proposal to radically simplify the tax system by eliminating or limiting deductions and other special preferences.

Achieving the goals the chairmen support will be difficult, however, without further attention to rapidly growing health care costs, and their ideas here are a bit sketchy. I believe we will eventually have to adopt a defined contribution plan for health care in which individuals receive a fixed subsidy for health insurance, based on their income and their health status. I am also skeptical that it will be possible to reduce spending and revenues to 21 percent of GDP given the aging of the population.

Obviously no plan, including this one, is perfect. But critics of the proposal, from Nancy Pelosi to Grover Nordquist, are living in an “Alice in Wonderland” world in which it is assumed we can go on borrowing money from other countries indefinitely with little or no consequences for the constituencies they represent. If the critics don’t like what the chairmen have proposed, the only responsible thing to do is to suggest an alternative that accomplishes roughly the same deficit reduction goals.

Our recent political debates have been marked by a great deal of silly and irresponsible rhetoric. In this steamy environment, the commission draft is a blast of cold but refreshing air. Let’s hope there are still enough grown-ups in America who understand the need for shared sacrifice to make the country strong again. Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson deserve our thanks for leading the way.

Deficit Reduction Depends on a Bipartisan Effort

William A. Galston, Senior Fellow, Governance Studies

Within hours after Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairs of President Obama’s bipartisan fiscal commission, made their draft budget public, soon-to-be-former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi declared that, “This proposal is simply unacceptable.” She went on to insist that Social Security and Medicare are “bedrock promises” that must be inviolate.

For his part, Republican anti-tax activist Grover Norquist had this to say: “Raising taxes is what politicians do when they don’t have the guts to govern.” The organization he heads soon put out a statement: the co-chairs’ report “confirms what everyone has known—this commission is merely an excuse to raise net taxes on the American people. Support for the commission chair plan would be a violation of the Taxpayer Protection Pledge which over 235 Congressmen and 41 Senators have made to their constituents.”

So there you have it. The left says the co-chairs’ plan is a breach of faith because it deals with everything—including Social Security and Medicare. The right says the plan is a breach of faith because it deals with everything—including taxes.

Taken together, these statements perfectly represent the polarization of our politics that is driving ordinary Americans crazy. Two high-quality post-election surveys confirm that large majorities of the people want the parties and the president to work much harder toward common ground.

The co-chairs’ plan is far from perfect, of course. It’s just the beginning of what will be a long and difficult discussion. But it’s a discussion that most Americans want to proceed. In the coming weeks, we’ll learn whether the commission’s members—who include many elected officials—have the courage to continue it … and if they do, whether President Obama will have the good sense to make it his own.

A Closer Look at Three Aspects of the Bowles-Simpson Tax Proposal

William G. Gale, Senior Fellow, Economic Studies

The proposal by the Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles (pdf), the co-chairs of President Obama’s fiscal commission, is a promising start to addressing the fiscal realities faced by policymakers and the American public. The proposal takes the fiscal problem seriously and proposes real—i.e., painful—solutions. The American public may not be ready to address these issues yet, but if the commission’s job is to get serious ideas on the table, the co-chair’s proposal is a welcome and important addition.

My comments focus on three aspects of the tax proposals: changes to the structure of existing taxes; the overall revenue level; and the possibility of new taxes.

The strongest part of the tax proposals is the effort to restructure existing taxes. It has long been a mantra in the tax policy community that broadening the base is the key to tax reform. Broadening the base makes taxes simpler (fewer deductions and exemptions for taxpayers to understand and document); fairer (different forms of income and spending are treated more similarly); and more conducive to economic growth (for the same reason). Base broadening also raises a lot of revenue, which can be used to reduce the deficit and/or tax rates.

The commission offers three ways to broaden the income tax base. One is simply to remove all tax expenditures. That outcome is unlikely, but illustrates how far we could reduce rates (8, 15, and 23 percent) by eliminating subsidies. The second is the Wyden-Gregg proposal (pdf), which is the only revenue-neutral, base-broadening, rate-reducing plan in Congress right now. The third is intriguing: the co-chairs propose a tax expenditure “trigger” that would restrict tax expenditures by 15 percent—until broad-based reform is enacted. This is a very good idea because it doesn’t hold base-broadening and revenue-raising hostage to major tax reform, which has only occurred once in the past 50 years.

I have significant concerns about the proposed revenue level—just 21 percent of GDP. Just maintaining current policies would cause non-interest spending to grow to nearly 26 percent by 2050; I question the wisdom of cutting total (interest plus non-interest) spending all the way back to 21 percent, which would require non-interest spending to be even lower. Yes, we should make significant cuts in spending—indeed, we have to—but the proposal tilts too far toward spending cuts and not enough toward revenue increases. In fact, if Congress did absolutely nothing on tax policy for the next 10 years, revenues in 2020 would be higher than if they enacted the co-chairs’ proposals. Rather than weighting the proposal toward spending cuts, a fairer and more effective solution would be to raise revenues in the 23-25 percent of GDP range.

The report is understandably silent on how to raise 2 to 4 percent of GDP in extra revenue, but this is not that difficult to do. One option is a new tax on energy (either a carbon tax, cap and trade system, or just an increase in the gasoline tax). A second option is a value added tax, which taxes consumption. VATs are work-horses of the modern tax system (my analysis of the VAT is here). Energy taxes would have the twin benefit of raising revenues as well as providing the right incentives for people and businesses to use cleaner forms of energy and help the environment.

While my preferred policy is somewhat different from the co-chairs’ report, it is worth emphasizing that the report is a very welcome addition to the debate. I would accept this plan over no plan.

The real issue is that people need to compare this plan not to the status quo but to other ways of closing the deficit. When the debate can finally turn to plan A versus plan B, rather than plan A versus the status quo, we will be having a real policy discussion. But as the first plan out of the gate, the Simpson-Bowles proposal is likely to receive a bad reaction from the public, if only because the public is not used to thinking in terms of one solution versus another. Still, Bowles and Simpson have done us all a great service by leading off the discussion.

It’s This Or Greece

Jonathan Rauch, Guest Scholar, Governance Studies

I’ll second my colleagues’ enthusiasm for the co-chairs’ mark. In the real world, plugging the budget hole is just about arithmetically impossible without a package of both tax increases and spending cuts, and the chairmen have mixed the components in a way that is probably as smart and fair as any plan can be. The question, of course, is political. Can it fly? Can anything like it fly?

Perhaps I should be alarmed that so many liberal Democrats are rushing to declare the chairmen’s draft dead before arrival. But I think the Dems know that spending is on an unsustainable course and needs to be cut. Certainly the president knows that. I think, when push comes to shove, he can round up enough Democratic votes to do a deal.

I’m more worried about the Republicans. On one level, of course, it’s a pleasant surprise that some Republicans seem willing to hold their fire against a package that includes higher revenues. But look at the intraparty dynamic that’s being set up. As Pete Wehner points out, you’ve got Sen. Jim DeMint, self-proclaimed enemy of big government, ruling out cuts to programs for seniors (Social Security; Medicare) and veterans—exactly the programs that make government big. Instead, he proposes cutting “administrative waste” (no kidding). And then, on the other hand, and appearing on the same edition of NBC’s “Meet the Press” as DeMint, you have Republican Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey, who says that everything should be on the table.

So you see what could happen here. Even if responsible Republicans want to vote for a grand bargain that includes much more in spending cuts than tax increases, they’ll have people like DeMint sniping at them from the rear. They’ll be looking at primary challenges from opponents claiming they sold out seniors and taxpayers.

To survive the crossfire from the chickenhawks in their own party, Republicans who are real fiscal hawks – -the ones who are willing to make hard, reality-based political choices instead of just bad-mouthing Big Government—are going to need political cover. Where could that come from? Not Obama and the Democrats. It will have to be the public. The fiscal reform plan needs to be big enough, bold enough, effective enough, and understandable enough to be sold to the public as the best, possibly last hope of getting out of the fiscal jam we’re in.

In other words, this can’t work like the stimulus or the health-care bill, in which reformers assume that good policy is its own justification. No, fiscal reformers need to operate from Day One on the premise that framing the debate is three-quarters of the battle. They need say, “It’s this or Greece.” And they need to be relentless in insisting that no one gets to criticize without putting forth an alternative.

A Deficit-Reduction Plan Rife With Problems

Henry Aaron, Senior Fellow, Economic Studies

The solutions to this problem will be painful and divisive. On the other hand, the plan is profoundly disappointing. Although it contains a number of proposals that budget analysts of both parties have long advocated, it sets unnecessarily strict targets that make needed political agreements needlessly difficult and it is vague where specificity is badly needed.

The above is excerpted from the Fiscal Times; read the entire piece here »

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Around the Halls: Reducing the Budget Deficit

November 12, 2010