Americans are bound to hear a lot about the urban/rural divide in the coming months as the 2016 general election heats up. A new report from the Pew Research Center describes growing Democratic domination of big cities, at the same time that Republican voters are becoming more concentrated in rural communities. Thus, the Washington Post frames Hillary Clinton’s recent visit to Western Pennsylvania and Ohio as stumping on “Trump terrain,” while Ron Brownstein notes that Trump heads a party “that has been almost completely routed from urban America,” and must thus rack up huge vote margins in rural areas to stay competitive.

Notwithstanding these political divisions, a close look at the data shows that urban and rural America are not as distant, economically or geographically, as the rhetoric may suggest.

The U.S. Census Bureau provides the most detailed definitions of urban and rural territory in the United States. The Bureau classifies more densely developed areas as urban, and identifies large clusters of urban territory (with populations exceeding 50,000) as “urbanized areas.” Urbanized areas, in turn, form the basis for identifying metropolitan areas, which approximate regional labor markets, and are the geography upon which researchers at the Metropolitan Policy Program focus most frequently (as our name indicates). The Census Bureau classifies areas not meeting these urban density thresholds as rural.

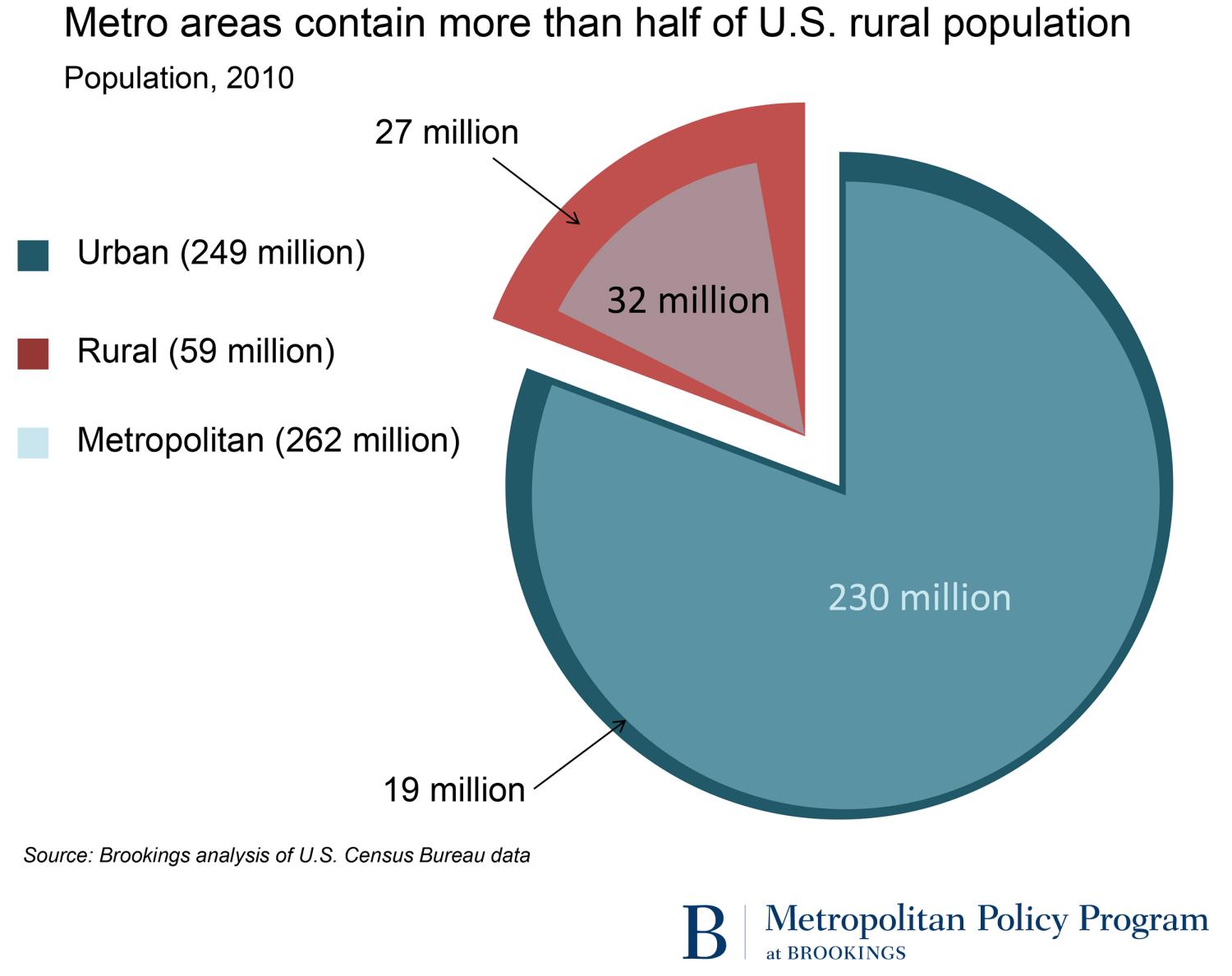

It turns out that a majority of rural Americans actually reside within metropolitan areas. Nearly 54 percent of people living in areas classified by the Census Bureau as rural also live in a county that is part of one of the nation’s 383 metropolitan areas. These 32 million residents of rural communities are thus part of wider labor markets that cluster around one or more cities, and most of them likely live within a reasonable commuting distance of those cities.

Of these “rural metropolitans,” a little more than half (17 million) live within the confines of one of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. Many of these large metro areas have sprawled into their surrounding countryside, so that residents of once-rural communities are now part of a larger urban labor market. For example, in the Pittsburgh metro area in 2010, roughly 420,000 of the region’s 2.4 million residents lived in low-density rural communities, especially in outlying counties such as Butler and Westmoreland. Even though many residents of those rural areas may live and work within small towns, their livelihoods are supported in part by the incomes that neighbors earn by commuting into Pittsburgh and its suburban environs.

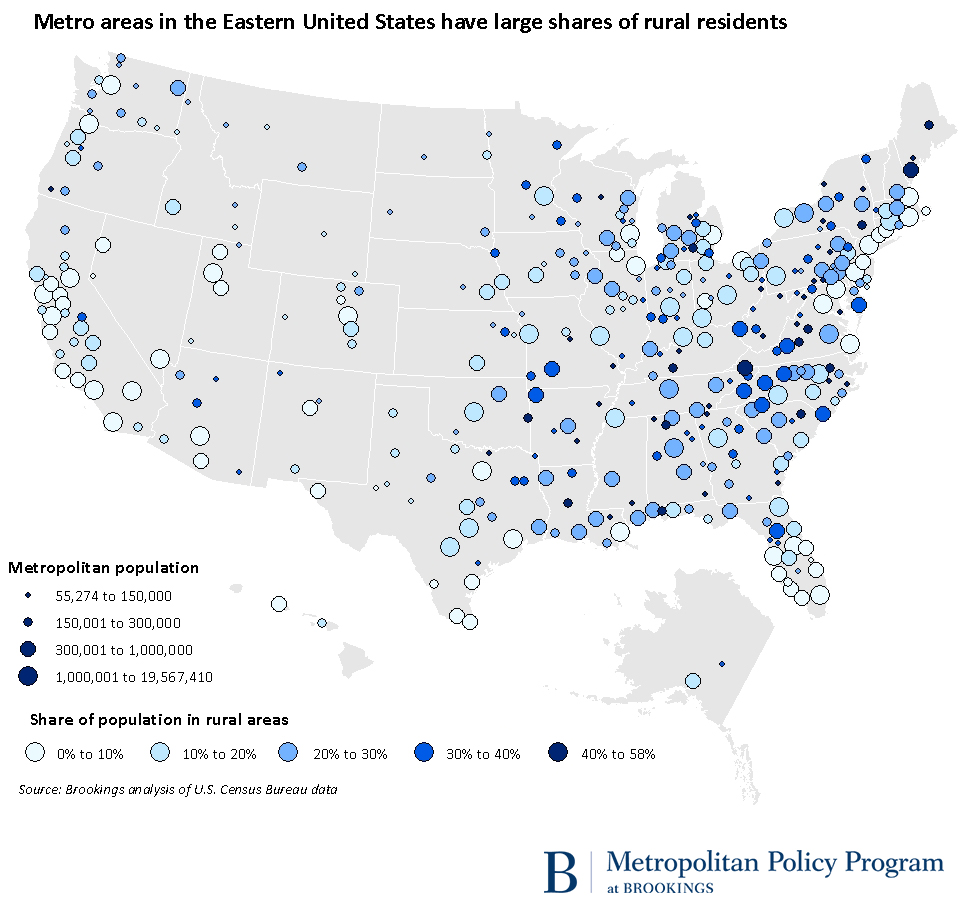

Regionally, many rural metropolitans live in either the Southeast or older industrial areas of New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Many metro areas in those regions of the country stretch across vast amounts of land where settlement is not impeded by oceans, mountains, or deserts, as it often is along the coasts and in the Western United States. Thus, three in 10 residents of the Winston-Salem, N.C., Jackson, Miss., and Knoxville, Tenn. metro areas live in rural communities. Greater Atlanta has the most rural residents (585,000) of any metropolitan area. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Miami, by contrast, environmental boundaries confine metropolitan residents to denser, urban areas.

Of course, this means that the other 46 percent of rural Americans live in small communities not particularly tethered to a city. Yet many of those communities are still interdependent with urban areas, as Brian Dabson has argued. Rural places contribute agriculture, energy, workers, natural amenities, and environmental stewardship to urban residents. Likewise, urban places provide jobs, markets, and specialized services for rural workers and businesses, while generating resources for investment back into rural communities.

In short, a metropolitan perspective suggests that rhetoric around the urban/rural divide in presidential politics obscures the economic destiny that these two camps often share.

Abigail Spector contributed research assistance for this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Political rhetoric exaggerates economic divisions between rural and urban America

August 3, 2016