On the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s War on Poverty, leading Republicans have been taking to the speaking circuit calling for new solutions.

“I would give us a failing grade,” Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), chairman of the House Budget Committee, told NBC News at an event last week. “It has failed. We should’ve done better than this. We can do better than this.”

Speaking at Brookings this week at a summit on social mobility, Ryan said federal antipoverty programs take a “haphazard, Whack-a-Mole approach… because the federal government created different programs to solve different problems at different times.” He continued, “There is little to no coordination among them.”

Ryan, who’s been traveling to low-income neighborhoods across the country for the past year to talk to local leaders, called for a more streamlined approach that allows for leadership from community members and the poor themselves. “Washington does not have all the answers,” Ryan told the crowd at Brookings. “Only the people in the community can solve the problems facing their community.”

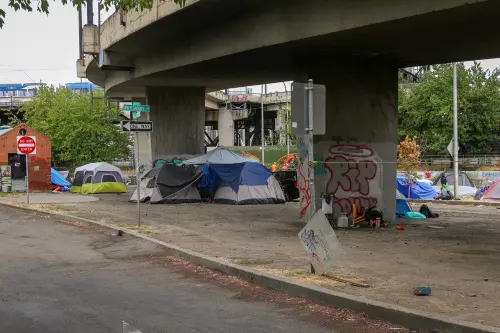

On his travels, Ryan may have seen that the landscape of poverty has changed a great deal since President Johnson was in office. For one thing, it has moved increasingly into the suburbs outside of cities like Milwaukee and Madison, not far from Ryan’s Wisconsin hometown of Janesville. More poor people now call the suburbs home than cities.

Yet federal programs designed to fight poverty two generations ago have not kept pace. Many suburbs have yet to build the civic infrastructure that cities have to help low-income families. Poverty in the suburbs often spreads across a larger geographic area than in cities, covering multiple jurisdictions that aren’t accustomed to working together. Federal antipoverty funding doesn’t do much to help spread necessary infrastructure, and presents obstacles to collaboration among providers and local governments.

Ryan’s remarks focused primarily on how people-based programs—like Medicaid, food stamps, and child care subsidies—could be blended to enhance coordination and remove work disincentives associated with program phase-outs. But that logic applies at least equally to place-based programs, such as those for affordable housing development, community health care, and low-income schools. Instead of giving small amounts of money to many fragmented on-the-ground actors, we can stretch limited federal investment further by encouraging greater collaboration and integrated problem solving at the state and metropolitan levels.

Ryan warned against policymakers who “sit in our think tanks in Washington and say, ‘Oh we’ve got the answer. It’s this program. It’s money here and money there.’” That being said, he might be pleased to read some of the case studies on our website and in Confronting Suburban Poverty in America. “Let’s talk to the people who are actually fighting poverty successfully,” Ryan told Brian Williams, “and see what we can do to support people there.”

We’ve talked to local leaders around the country, and it’s clear that we should invest more in organizations that are able to confront both urban and suburban poverty at scale. Greater Houston’s Neighborhood Centers is blending more than 30 federal government funding streams to serve clients at more than 60 sites across the region. IFF (formerly Illinois Facilities Fund) is providing crucial research and lending services to regions across the Midwest to help develop needed services like affordable and supportive housing in their communities. Those are bottom-up models worth spreading.

They are also one step ahead of Senator Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) who, in a speech last week, called for turning federal antipoverty funding over to the states in the form of a “Flex Fund”—block grants that would presumably combine all manner of people- and place-based antipoverty programs.

That’s a bridge too far. Federal programs like food stamps, Medicaid, and the EITC are effective (something that those who deem the War on Poverty a “failure” conveniently ignore) precisely because they work harder when poverty rises, something block grants don’t do. But some incremental steps in Rubio’s direction would undoubtedly help. Our proposed Metropolitan Opportunity Challenge would repurpose a fraction of existing place-based federal antipoverty funding to enable more regional solutions to poverty. The challenge would award resources to states though a competitive process, encouraging state and local governments to organize programs and delivery systems in creative ways that focus on real outcomes for people and places.

“It’s wrong for Washington to tell Tallahassee what programs are right for the people of Florida,” Rubio said. “But it’s particularly wrong for it to say that what’s right for Tallahassee is the same thing that’s right for Topeka and Sacramento and Detroit and Manhattan and every other town, city, and state in the country.”

The rise of suburban poverty adds relevance and urgency to Rubio’s and Ryan’s calls for greater local autonomy in the next War on Poverty. Far short of dismantling the federal safety net altogether, though, there are smart, bipartisan moves we can make right now that build on local successes in addressing the new landscape of poverty.

Commentary

The GOP and the Next War on Poverty

January 16, 2014