President Obama has called for higher taxes on capital gains, to generate revenue to help middle and lower-income families. Is there also a social mobility case for action?

Ending the “Step Up” Unfairness

One specific proposal has gained a lot of attention: closing a loophole in our laws concerning inheritance. Currently, any capital gains accrued over a person’s lifetime are not taxed when the person dies, because the value of the assets is “stepped up” at death, creating a new basis for one’s heirs. Say your billionaire father bought a tract of land in 1950 for $200,000. Now he passes away and the land is worth $3,000,000. You inherit the land. The “stepped up basis” rule means that—if you sell the land—you pay capital gains tax on any appreciation above $3,000,000, not on appreciation above the original value, $200,000. So if you sell the land immediately, you will pay no capital gains tax. Without this loophole, you’d pay a 23.8% capital gains tax on the $2,800,000 in appreciation; the government would get $666,400, and you’d leave with $2,333,600.

The President exempted closely-held family farms and businesses along with any appreciation in the value of one’s principal residence, to ensure that the proposal targets only the truly wealthy. The rule means a lot of lost revenue: in 2012, the OMB estimated that “stepped-up basis” would cost the government $400 billion over 5 years.

Piketty and the Social Mobility Case

The Washington Post’s Matt O’Brien aptly sees the proposal as evidence of “Obama’s Piketty moment.” Given Republican opposition, the chances for the proposal are vanishingly small. But there is a good case for it beyond sensible fiscal policy: the nation’s limited social mobility and increasing concentrations of both income and wealth.

The fear of Piketty and others is that rising income inequality over the last four decades will eventually lead to greater wealth inequality as the “haves” are able to sock away larger amounts of savings, while the “have-nots” increasingly struggle to do so. With greater concentrations of wealth will come bigger inheritances, as the richest Americans pass on fortunes to their children. Intergenerational social mobility could decline, as inherited wealth grows in importance relative to self-made wealth.

Three Reasons to Be Afraid on Wealth Inequality

Are the Piketty fears justified? Three warning signs suggest they might be:

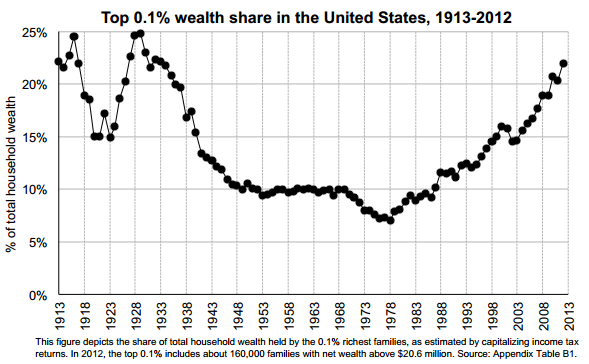

- Wealth concentration. The share of total wealth owned by the top 0.1 percent increased from 7 percent in late 1970 to 22 percent in 2012, according to a new paper by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman:

Source: Saez and Zucman, “Weath Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” NBER Working Paper, 2014. - Inheritance Matters. An estimated 35 to 45 percent of wealth is inherited rather than self-made, according to Kopczuk’s review of the literature.

- Inheritance Could Hurt Mobility, especially when combined with the other advantages that wealthy parents provide their children (such as more engaged parenting, better schooling, help with paying for college or investing in a home, and all kinds of social capital or useful connections). As Richard Reeves argues, wealth could help to create a “glass floor”, below which children in privileged families cannot fall.

Tax Estates, Invest in Opportunity

An obvious way to reduce intergenerational transfers of wealth is to increase taxes on inheritances. Currently, inherited wealth can be passed tax-free to a surviving spouse, and then on to one’s children unless the estate is larger than $5,430,000. (Above this amount, estates are taxed at 40 percent.)

Because the exemption is so generous, less than 1 percent of all estates are ever subject to the tax, and even non-exempt people leave large amounts of money to their children. With the retirement of the baby boomers beginning, trillions of dollars hang in the balance. The President’s proposal to tax capital gains at death, although administratively complicated because of the need to keep track of the initial basis, would help to whittle some of these bequests down to size.

Republicans have been intent on eliminating the estate tax entirely and succeeded in lowering it during the 2000s. The top rate fell from 55% in 2001 to 35% in 2012. The top rate rose to 40% as part of the “fiscal cliff” deal. But the exemption jumped from $675,000 in 2001 to $5,430,000 in 2015. Growing concerns about social mobility on both sides of the aisle make the issue of inherited wealth a topic that should be on the agenda.

Downton Abbey? No Thanks.

Republicans, in particular, have been eloquent about the ability of each generation, with only modest help from their parents or the larger society, to make it on their own. And as the Gates family has argued, the very wealthy should be willing to repay society for the many benefits they have derived from being born in the U.S. Yes, hard work and risk-taking often lie behind large fortunes, but they also reflect the luck of the draw and should not be allowed to create a Downton Abbey society in our midst.

Commentary

Wealth, Inheritance and Social Mobility

January 30, 2015