America’s coal workers and their communities are hurting. Coal consumption is declining—both at home and abroad—due to market forces and the search for clean energy, and the decline is creating ripple effects across coal-reliant economies that begin with job losses and spill over to cause a host of economic and fiscal problems.

The jobs picture has been especially bleak for coal workers over the past year, with large layoffs occurring in even the most productive coal plants. Just last month, one of America’s most productive coal plants, in Wyoming, laid off 15 percent of its workforce. In Magoffin County, Kentucky, where coal production dominates local industry, unemployment reached 21.6 percent.

In new research published at Brookings this week, I take a closer look at how declines in coal production have impacted coal workers and local economies and consider industry projections for the coming decades. I show how it would be a risky bet to rely on a rebound in the coal sector to improve coalfield economies and how federal support will be necessary to help dislocated workers, their families, and retirees. Though several policy proposals have emerged to address the concerns of coal-reliant areas, there’s a striking disconnect between the urgent needs in coal country and the level of funding currently available to meet those needs.

There are solutions, though. If designed intelligently, the most cost effective climate policy approach—taxing or otherwise putting a price on carbon—could help fund the transition in coal communities. The future of coal in the United States is unpromising, with or without a climate policy, but nearly any serious measure to control greenhouse gases will amplify existing declines.

The regulatory approach the Environmental Protection Agency is pursuing under the Clean Air Act offers no way to alleviate disproportionate burdens on coal communities. In contrast, a carbon tax could raise ample revenue to not only assist in the transition but also offset burdens on low income households across America.

Why coal consumption is on the decline

In 2015, coal production in the United States totaled 890 million short tons, 24 percent below its high of 1.172 billion short tons in 2008. Over the last year, the declines have accelerated. Total U.S. weekly coal production fell by 39 percent from early April 2015 to early April 2016. The drop was particularly acute in Appalachia, where weekly coal product fell by 43 percent in that one-year period.

A number of factors are at work in these trends: slow growth in U.S. electricity demand; competition from natural gas at historically low prices; declining exports; and state and federal environmental and clean energy policies. For a while, booming growth in China had many thinking strong exports might revive U.S. coal production, but now China’s in a slowdown and the United States faces tough competition for the remaining imports. As of the third quarter of 2015, coal exports from the United States had declined for ten quarters in a row.

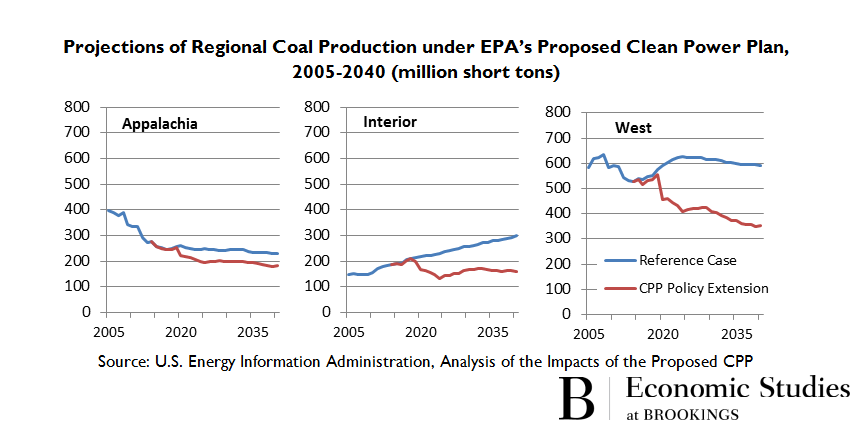

Policy changes are likely to cloud coal’s future further. The Supreme Court recently issued a stay of the implementation of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) rule, which the agency projects would reduce carbon emissions from existing fossil-fueled electric power plants by 32 percent relative to 2005 levels, or about 17 percent relative to 2012 levels. Despite the stay, however, some states are continuing their compliance planning. Whether the rule survives in its original form or not, it appears that long term planning in the electricity sector is leaning heavily away from coal.

Ripple effects of coal layoffs for state and local governments

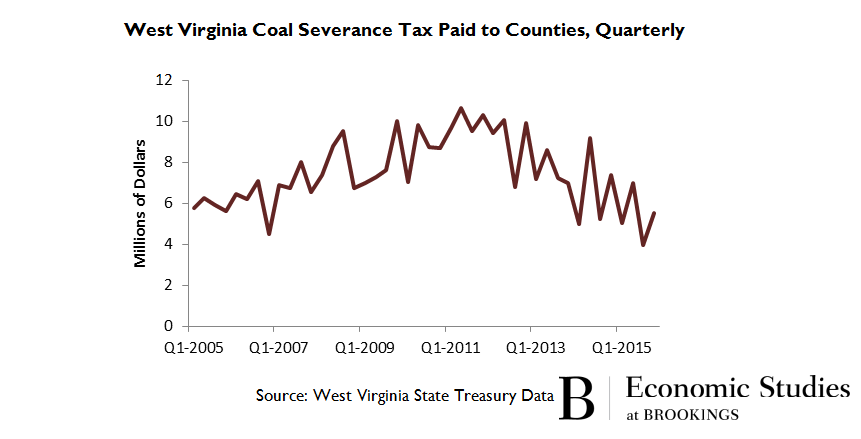

Coal-related layoffs and bankruptcies come at a steep cost for workers and their families, but they also create broader economic problems for communities. The economic activity associated with coal production, including severance tax revenues, wages, property values, mine retiree benefits, and ancillary business activities are vital to the economic health of state and local governments. West Virginia, for example, distributes 75 percent of its net state coal severance tax to coal-producing counties. The figure below shows how those transfers have eroded over the past few years and hints at the potential fiscal problems facing local governments as coal production falls.

What policymakers have done so far to help coal communities

Policymakers have recognized for some time the need to help dislocated coal workers and to protect retirees. The Obama administration has put forth several budget proposals—some funded and underway, others not—bundled as the POWER+ Plan, to support economic diversification, workforce retraining, and other activities. Various Presidential campaign pledges and draft bills have proposed assistance, but to-date Congress has not yet provided the broad support needed to address the many challenges discussed in this post. And whatever the assistance proposed by Congress or the Administration, we need a way to pay for it.

If we combine the amount needed for job training, infrastructure, and revitalization of coalfield communities with the estimated $2.3 billion needed to protect retiree benefits and resources needed to reclaim abandoned mines, a very rough estimate of the funding needed is in the tens of billions of dollars over a decade.

How a carbon tax could fund programs to revitalize coal country

Advocates for coal workers and communities would be the first to point out that, on the surface, a carbon tax would hurt an already struggling industry. In some ways, they’re right: taxing carbon would disproportionately reduce coal use relative to other fuel types. That is both because it is the most carbon-intensive fuel (with about twice the emissions per unit of energy as its fossil competitor, natural gas) and because coal has so many lower-carbon substitutes in its chief market, electricity generation, such as renewables, natural gas, and nuclear. Indeed, a carbon tax would probably depress coal consumption as much or more than any other significant climate policy approach.

But a carbon tax doesn’t need to be all bad news for the coal community. As documented in my new research, coal consumption and production is on the decline for many reasons, and is unlikely to rebound any time soon. What coalfield communities need now is to move on their transition before things get worse. To do that, they need funding, which a carbon tax is uniquely suited to provide.

An analysis from the Tax Policy Center’s Donald Marron, Eric Toder, and Lydia Austin estimates that a carbon tax that starts at $25 per ton of CO2-equivalent emissions and increases by two percent above inflation each year would produce net revenue of about $90 billion in the tax’s first complete year and about $1.2 trillion over its first decade. Just three percent of the revenue over a decade could raise $36 billion for the transition. And that revenue projection is even lower than what might be raised by a piece of legislation introduced last year by Congressman John Delaney (D-MD), which would start the tax at $30 per ton.

Thus a carbon tax can raise more than enough revenue in the first ten years to fund a generous transitional assistance package for coal workers and communities and still allow for tax reform and other objectives that could motivate a legislative deal.

A new way forward

Coal-reliant communities across America are suffering, and policymakers need solutions. Many proposals have been offered, but their scale is too small for an appropriate package of support. By replacing Clean Air Act regulations with a tax on the carbon content of fossil fuels and other greenhouse gas emissions, the U.S. could provide coal workers and communities with more-than-ample resources, while at the same time producing superior environmental and macroeconomic outcomes.

A well-designed carbon tax could be a win-win for coal communities and the environment. It’s time we give it a closer look.

Editor’s note: Morris is an unpaid advisor to Hillary for America’s Energy, Climate, and Environmental Policy Working Group. Delaney Parrish contributed to this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Coal economy workers need help—and a carbon tax could provide it

April 26, 2016