Six months into the Biden administration, amid the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and increasing violence on the ground there, the U.S.-Pakistan relationship stands in uneasy limbo. Pakistan has indicated repeatedly that it wants the relationship to be defined more broadly than with regard to Afghanistan — especially based on “geo-economics,” its favored current catch-all for trade, investment, and connectivity — and has insisted that it doesn’t want failures in Afghanistan to be blamed on Pakistan. At the same time the U.S. has made it clear that it expects Pakistan to “do more” on Afghanistan in terms of pushing the Taliban toward a peace agreement with the Afghan government. Pakistan responds that it has exhausted its leverage over the Taliban. The result is a relationship with the Biden administration that has been defined by Pakistan’s western neighbor, as has been the case for U.S.-Pakistan relations for much of the last 40 years. And the situation in Afghanistan may define the future of the relationship as well.

What Pakistan wants

Pakistan’s official stance is that it would prefer a peaceful outcome in Afghanistan, some sort of a power-sharing arrangement reached after an intra-Afghan peace deal. Many are skeptical of this given Pakistan’s support of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in the 1990s, and the sanctuary the group later found in Pakistan. But Pakistan argues that a protracted civil war in Afghanistan would be disastrous for it, on three dimensions: First, insecurity from Afghanistan would spill over into Pakistan. Second, Pakistan fears that this would set up space for the resurgence of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a group responsible for killing tens of thousands of Pakistani civilians and attacking the country’s army, security forces, and politicians. Third, this would increase the amount of refugee flows to Pakistan (which has hosted millions of Afghan refugees since the 1990s, including 3 million at present), which it can’t afford. These are well-founded fears.

Pakistan is less clear about what a Taliban military victory would mean for it, but discusses it in the same vein as the possibility of civil war in Afghanistan. The implication, presumably, is that the road to a comprehensive Taliban military victory would be violent, setting up many of the same concerns identified above. As part of the Extended “Troika” on Peaceful Settlement in Afghanistan — which also includes the U.S., China, and Russia — Pakistan has signed a statement saying a Taliban emirate would be unacceptable to it.

What Pakistan doesn’t discuss openly is this central tension: Pakistan has long treated the Afghan Taliban as friends — preferring them to Pashtun nationalists (which it viewed as threatening, fearing that they would mobilize Pashtuns on the Pakistani side of the border as well) and to the current Afghan government (which it sees as friendly with India) — while the Afghan Taliban’s friend and ideological twin, the TTP, has posed an existential threat to Pakistan and killed tens of thousands of Pakistanis. This tension is clearly making Pakistan nervous. Pakistan routed the TTP in military operations starting in 2014, but many of them sought refuge across the border in Afghanistan, and have been regrouping since last year. The Afghan Taliban’s potential rise in Afghanistan will almost certainly embolden the TTP, and threatens to engulf Pakistan in the kind of violence it experienced between 2007 and 2015. There’s some speculation that Pakistan could work out a deal with the Afghan Taliban to constrain the TTP, but even if it comes to pass, there is a real question of how effective it would be.

This tension is not apparent to Pakistan’s public. You’ll see Pakistanis being supportive of the Afghan Taliban and against the TTP, because the Pakistani state has obfuscated the connections between the two groups. The only time top officials have admitted to these recently is behind closed doors, when the army chief and the head of the military intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) called the Afghan Taliban and the TTP “two faces of the same coin.”

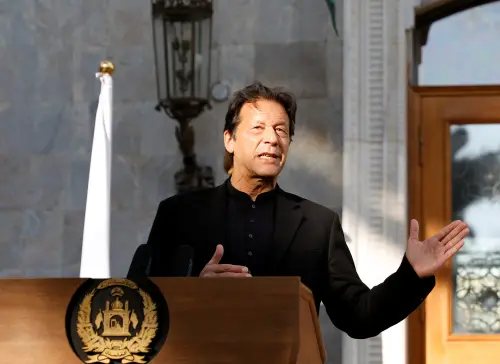

Amid the increased violence in Afghanistan, with fingers being pointed at Pakistan’s relationship with Taliban, Pakistan has been trying to distance itself from the group. Prime Minister Imran Khan recently said that Pakistan doesn’t speak for the Taliban, nor is it responsible for it. Pakistan argues that a “rushed” U.S. withdrawal before peace talks has set the stage for the current situation. Khan has said that the Taliban’s battlefield victories render moot any leverage Pakistan could have over it. He’s even disingenuously argued that the Taliban are hiding among Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

Yet the world remains skeptical, amid reports of purported Taliban fighters being treated across the border in Pakistan, and statements such as those made by its interior minister, who recently said that the Taliban’s families live in Pakistan.

What America wants

From America’s perspective, the main ask is for Pakistan to exercise its leverage in pushing the Taliban to reduce violence and toward an intra-Afghan peace deal. The second is the potential for counterterrorism cooperation in the post-withdrawal landscape. But a checkered past colors the relationship. For Washington, part of the reason it lost the war against the Taliban is because the Taliban found support in Pakistan, including sanctuary for the Haqqani network and the Quetta shura. That Osama bin Laden was found in Abbottabad in 2011 eroded any remaining trust from the U.S. side. Yet as matters stand, America still needs Pakistan’s help in the region, especially as it withdraws from Afghanistan. And Pakistan largely delivered on the Trump administration’s main request, to bring the Taliban to the table for talks with the United States.

There is some question of what U.S. discussions with Pakistan for counterterrorism cooperation have entailed — “bases” in Pakistan are a nonstarter in Islamabad, and a question that may not even have been asked, though it occupied the domestic conversation for a time. Yet intelligence sharing and other forms of cooperation are presumably all on the table and being discussed behind closed doors.

The sticking points from the U.S. side, however, remain: a wariness about trusting Pakistan, and a desire for Islamabad to put pressure on the Taliban. Pakistan argues the requests to “do more” from the U.S. side are never-ending.

The terms of engagement

President Joe Biden still hasn’t — somewhat inexplicably — called Prime Minister Khan. But U.S.-Pakistan engagement continues, mainly on Afghanistan. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi have spoken multiple times. U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad continues his visits to Islamabad and Rawalpindi, including one in July. Central Intelligence Agency Director Bill Burns visited Pakistan in a secret trip that was later made public. Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa has received multiple calls from officials in Washington, including from Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin. The countries’ national security advisors have met twice in person, and the ISI chief visited Washington just last week. A new quadrilateral relationship has been announced between America, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan. The U.S. has also delivered millions of doses of the Moderna vaccine to Pakistan to aid its pandemic response. Yet despite all this, there has been no movement on intra-Afghan peace talks beyond a set of inconclusive meetings in Doha in July — and the situation in Afghanistan is worsening rapidly. As it deteriorates, it appears the U.S. is in wait-and-see posture in terms of the relationship with Pakistan.

Stark choices

As for the future, it is becoming obvious that Pakistan will find it impossible to separate itself from what happens in Afghanistan. As the Taliban gains ground, fingers are pointed toward Pakistan’s relationship with the militants. Whether Pakistan likes it or not, whether this is unfair given Afghan, U.S., and Russian responsibility for bad outcomes in Afghanistan, the reality is that the world sees a Taliban advance as a product of Pakistan’s long-alleged double game. This means that there will be little to no appetite in Washington to engage with Pakistan on other matters going ahead if Afghanistan is embroiled in violence or in Taliban hands. (Pakistan’s closeness with China won’t help it either, in an era of increasing U.S. confrontation with Beijing.)

If Pakistan truly means what it says about wanting a peaceful Afghanistan, then it is time for it to exert all the effort it can to force the Taliban to cease violence and come to the table for peace. No other country’s interests would be better served — in terms of domestic security, international standing, and the relationship with America — by such an effort than Pakistan’s own. The Taliban will be recalcitrant given its newly garnered international legitimacy, beginning with the U.S.-Taliban deal and continuing with its current travels around the globe, and its recent battlefield victories. Yet Pakistan has no other choice but to put pressure on it, for its own sake, and certainly for its neighbor next door. Pakistan’s alternative — betting on the Afghan Taliban while at the same time planning to tackle a resurgent TTP at home — will be disastrous, both for itself and for Afghanistan.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

An uneasy limbo for US-Pakistan relations amidst the withdrawal from Afghanistan

August 6, 2021