The world appears under siege from dark forces of violence, xenophobia, corruption, and conflict. The latest reporting from watchdogs like Freedom House, Transparency International and Human Rights Watch remind us that recent trends are negative; democracy is in recession; and progress toward peace, development, and human rights is waning.

Some proclaim a crisis in confidence among leading democracies as they wrestle with economic downturns, persistent inequality, growing migration demands, and political stalemate. One need only look to the catastrophe unfolding in the Middle East to conclude that we have entered a new, more dangerous period that threatens fundamental precepts of the international liberal order constructed over the last 70 years.

Rising tides?

But is it really so dire? Strong currents of change that have taken shape since the early 1990s are pulling toward more optimistic scenarios:

- the number of people living in systems that give them a voice in electoral democracies has doubled since 1989 to over four billion,

- one billion people have risen out of poverty,

- the death rate for children under five has been cut in half,

- more people are living longer and healthier lives,

- millions more girls and boys are enrolled in school,

- deaths from conflict in the developing world have fallen by 75 percent,

- average incomes have nearly doubled, and

- food production has increased by half.

The Sustainable Development Goals approved by world leaders last September set forth a list of ambitious but achievable targets designed to build on these successes, and climate change is finally getting the collective attention and action it deserves. The international machinery to address human rights violations has never been more responsive to the growing demands for monitoring and accountability of abuses.

Despite these more positive features of the international liberal order, its fate has never felt more precarious.

Despite these more positive features of the international liberal order, its fate has never felt more precarious. Various geopolitical and economic factors—aggressive moves by China and Russia to stifle dissent and disrupt international norms as they cope with economic downshifts, as well as the spreading instability and conflict in the Arab world—exacerbate fears that we may be reaching a tipping point in which our collective efforts to build a more peaceful, democratic, and prosperous world will be replaced by a much more divisive and chaotic situation.

New kids on the global power bloc

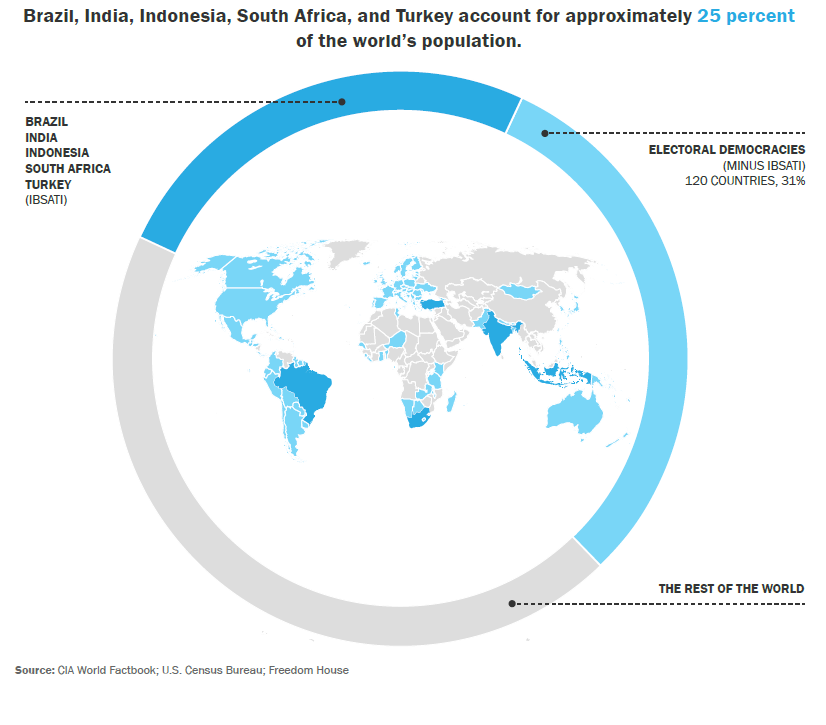

In this sea of uncertainty stand five rising democracies: India, Brazil, South Africa, Turkey, and Indonesia. Their fortunes will likely play a decisive role in the world’s ability to sustain and strengthen the international liberal order.

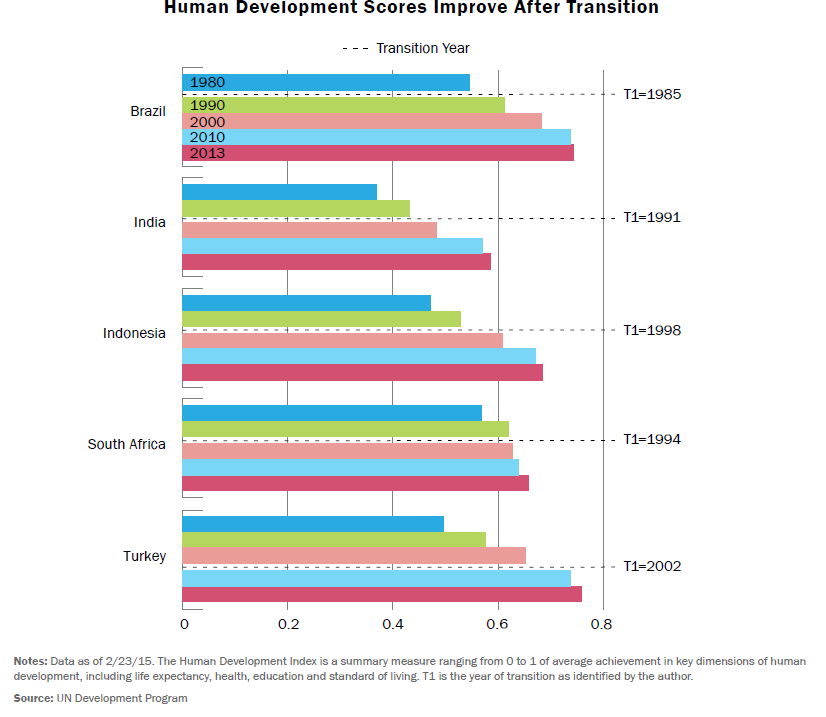

The good news is that each of these diverse countries—which collectively represent 25 percent of the world’s population—has emerged from painful periods of dictatorship, apartheid, and colonialism to embark on a path toward more open societies, improved human development, and more widespread prosperity. Their average GDP growth rates over the past 30 years have been consistently above the global average and until 2014 regularly outperformed China on a per capita basis. Since their respective transitions to more liberal and competitive systems of political and economic governance, they have made major strides in securing political rights and civil liberties. They’ve also reduced debt and controlled inflation, and made significant improvements in key dimensions of human development (defined as a long and healthy life, access to knowledge, and a decent standard of living). Life expectancy improved, poverty rates dropped, literacy grew, and infant and maternal mortality fell significantly. Most importantly, they achieved these outcomes in tandem with democratization, underscoring the virtuous circle of political and economic liberalization and offering a positive antidote to the restrictive model of China’s state-dominant development.

On the negative side, it is increasingly clear that all five countries have a long way to go to secure democratic stability for their growing populations. Recent indicators are indeed worrisome, particularly in Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, where significant backsliding in freedom of the media and Internet and reconciliation with the minority Kurdish population are well documented. The entrenched power of the African National Congress in South Africa is breeding corruption and popular frustration with dashed expectations. A twin political and economic crisis in Brazil is raising serious doubts that its fractious political system can keep the country on course. And Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reluctance to keep his Hinduvta supporters in check and govern on behalf of all Indians is complicating the country’s otherwise resilient economy.

Overall, compared with other democracies, these five are neither shining stars nor declining laggards. A sustained deterioration of their otherwise positive trajectories, however, would send a very bad signal about the ability of liberal democracies to deliver tangible benefits for their citizens.

A sustained deterioration of their otherwise positive trajectories, however, would send a very bad signal about the ability of liberal democracies to deliver tangible benefits for their citizens.

Join the club

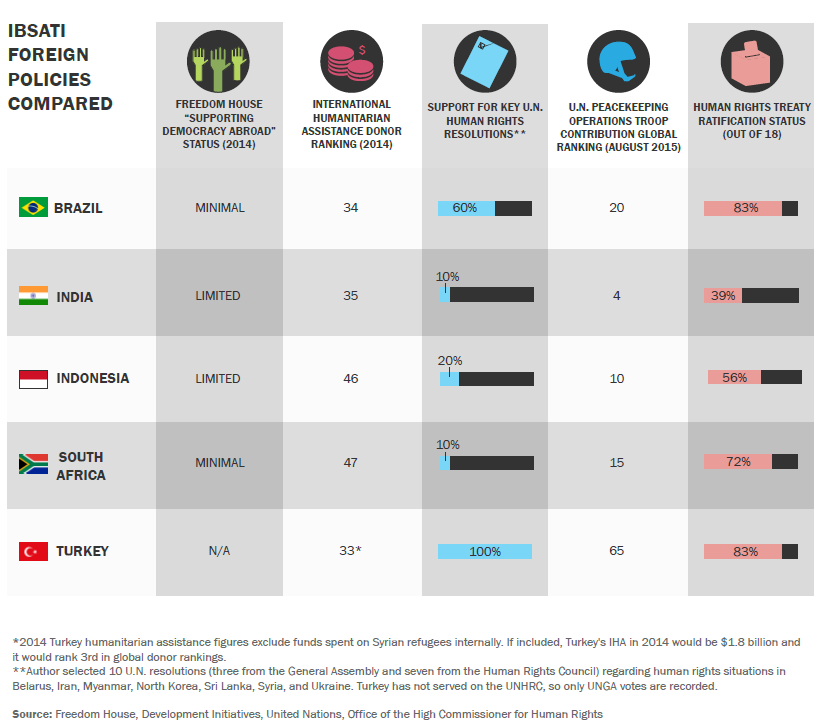

Even more worrisome, perhaps, is the unwillingness of these five countries to step up on the global stage to the responsibilities that come with their growing legitimacy as liberal democracies. Although they’ve increased contributions to international peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance, their foreign policies largely remain stuck in old-fashioned concepts of noninterference in other states’ concerns, or swing unpredictably between interest-based strategic autonomy and an erratic concern for democratic progress and human rights around the world. Determined to be friends to all and enemies of none, they choose to sit on the sidelines in the face of obvious threats to the international liberal order.

Determined to be friends to all and enemies of none, they choose to sit on the sidelines in the face of obvious threats to the international liberal order.

Long memories of external support for anti-democratic forces in their own countries and more recent experiences with heavy-handed interventions in places like Libya and Iraq position them against the West when it comes to collective action to defend international peace and security. The concept that expansion of democracy and human rights around the world will lead to better security and development outcomes—which undergirds the marriage of interests and values that drives much of the West’s foreign policy agenda—is largely missing from their thinking. And stakeholders from parliaments, think tanks, the media, and NGOs are only beginning to catch up to their governments’ mixed records. The result is a widening gap between these countries’ status as liberal democracies and their behavior as responsible global leaders.

If we are to sustain the positive trends toward more open societies and greater international cooperation against threats to our common humanity, we will need to find new ways to consolidate and modernize the global consensus behind universal norms. For starters, established democracies need to practice at home what they preach abroad. They also need to revisit their tendency to intervene first and ask permission later and instead pursue diplomatic approaches that include rising democracies in meaningful ways.

Emerging powers should reconcile their embrace of democratic norms at home with a more robust approach to support political reforms abroad. A concerted effort should be undertaken by all democracies to find common ground on priorities like civil society freedoms, economic and social rights, quality education for women and girls, anti-corruption and freedom of information, and the Internet. The United States should use its current presidency of the Community of Democracies to build such a consensus among both old and new democracies. If these steps are taken, the fate of the international liberal order will stand a much better chance of coming out of its current crisis even stronger.

Ted will be discussing the findings from his new book tomorrow at the second Brookings Book Club, register to attend here. Ted also discussed the book on the latest episode of the Brookings Cafeteria podcast. Finally, we also have an interactive slideshow showing trends in these five emerging democracies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is the international liberal order dying? These five countries will decide

February 17, 2016