To paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of the decline of United States leadership in the world economy are greatly exaggerated. The Hamburg G-20 summit actually underscored its importance. Despite major differences between the U.S. and other world powers on headline issues of trade and climate change, the effort made by leaders of other countries to accommodate the positions of the U.S. was significant.

So what did the G-20 accomplish? To answer this, look at the various documents on which agreement was reached. There are 15 of these, dealing with topics including climate and energy, the United Nation’s Agenda 2030, a special partnership with Africa, marine litter, anti-corruption, rural youth employment, and women’s entrepreneurship. Humanitarian aid was given a financial shot-in-the-arm and, importantly, was linked directly to longer-term efforts to address underlying causes of recurrent and protracted crises.

Every G-20 summit is the culmination of a year’s worth of work-streams over a broad agenda, that together aim to bolster collective action on some of the world’s thorniest problems. In its analysis of the previous G-20 Summit, in Hangzhou, China, the University of Toronto identified 213 commitments across 19 areas made by G-20 leaders. The final compliance report made by the independent researchers suggests an average implementation success rate of 80 percent, with Canada, the European Union, Australia, Germany, and China in the lead, while Italy, Saudi Arabia, and the U.S. lagged behind. The U.S. scores were dragged down by poor compliance on fossil fuel subsidies, climate change, and e-commerce, but it scored highly on most other areas, including energy efficiency, financial sector reform, international taxation, and investment promotion.

The point is that on a far-ranging agenda, most countries contribute more in some areas than in others, and many backtrack on at least some areas. This same pattern emerged in hashing out the commitments made at Hamburg. The differences between the U.S. and others were more visible than in previous summits, but there were also significant areas where collective action could be agreed.

It is in these detailed work-streams that the impact of the G-20 is felt. While most press commentary has focused on personal dynamics between leaders—such as who sits at which table, perceived slights, and compliments and body language issues—the substantive work moves forward behind the scenes, receiving endorsement from leaders at the summit or, in some cases, breakthroughs where negotiators failed to reach agreement beforehand.

Here are some of the more prominent compromises made by leaders. Trade stands out: In an area where the risk of derailment was high, and given disagreements at the last finance ministers’ meeting, the leaders’ communique appears to have found a compromise. There is a basic reaffirmation of a rules-based, order, with the major multilateral trade institutions being name-checked. Trade defense instruments must be “legitimate.” Steel is dealt with in a separate paragraph, and follows a previously agreed upon G-20 process, not a unilateral one.

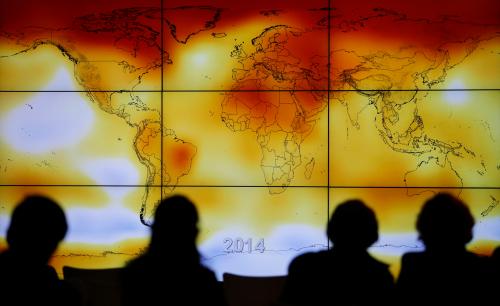

Climate change is another area where accommodation was needed. There was no effort to hide the main disagreement over the Paris Agreement and, perhaps for the first time in a G-20 communique, there was an open acknowledgement that consensus could not be found. Nevertheless, some areas of commonality emerged: “We remain collectively committed to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions… [we] support financing by multilateral development banks to promote universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and clean energy.” The end game of transforming economies and energy systems consistent with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was reaffirmed by all countries, but differences emerged as to the means of getting there. The U.S. tantalizingly announced it would cease implementation of its current Paris commitments, but committed to an approach that would lower emissions.

It would be naïve to suggest that the outcome on climate change is adequate. It is not. But there is relief that the U.S. is committing to the long-run objectives of transformation toward a low-carbon economy, and will, hopefully, continue to contribute in areas such as liquefying natural gas and energy-efficient combined cycle thermal plants where it is a global leader.

Sections on digitalization, employment and skills, financial sector resilience, the international financial architecture, international tax cooperation, international health regulations (and a commitment to eradicate polio), anti-microbial resistance, women’s empowerment, food security, water sustainability, resource efficiency, anti-corruption, and Agenda 2030 are noteworthy for their continuity with and natural evolution from prior G-20 work. New programs like the Africa Partnership suggest a much-needed focus on that continent’s problems. Together, these represent systematic steps forward to achieving the objectives of strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive growth that is now the vision for the G-20.

In reality, many of these results from the Hamburg G-20 look mundane, even boring. The G-20 Marine Litter Action Plan did not garner headlines, but might help reduce the 8 million tons of plastic that end up in our oceans each year, often leaching harmful chemicals. The G-20 during non-crisis years operates on the principle that many little steps are needed to create a critical mass for change.

The take-away: U.S. power has not diminished, but it has chosen not to exercise the leadership that comes with power at this G-20 Summit. The “boring” parts of the agenda have continued to make progress, even though they do not make for good headlines. That’s a tribute to solid bureaucratic work that continues behind the scene. The relief is that there was no effort to diminish or otherwise dilute the role or functioning of the G-20 as an institution. The U.S. came across not as a country with strong anti-multilateral views (except on a couple of headline items) but rather as a country with no substantive, positive agenda. The U.S. is still the only country with the power to take leadership in the near term, but it must move away from the distractions of no-win fights on trade and climate and get back to leading other countries in shaping solutions to global problems.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The G-20 steadily progresses

July 11, 2017