Firmin has been a survivor: street vendor, carpenter, and gardener. Two years ago he arrived in Abidjan from his village with the ambition to join the National Police School but was unable to do so. The story of Firmin reflects the story of hundreds of thousands of young Ivoirians who enter the domestic job market every year. Today, there are about 14 million workers in the country, but that will rise to around 22 million by 2025. The question remains whether there will be enough good-paying jobs for everyone.

Almost all Ivoirians today are employed in some way. But their main challenge is not to find a job but to find one with which they can earn a decent income. An average worker earns the equivalent of $200 per month, lower than the average in sub-Saharan Africa. The Ivorian labor market is highly segmented, with 80 percent of workers in self-employment and in household enterprises or farms, earning less than the equivalent of $120 per month. At the top end of the scale, few workers have the opportunity to earn more than $2000 per month or more, including those working in the mining and banking sectors.

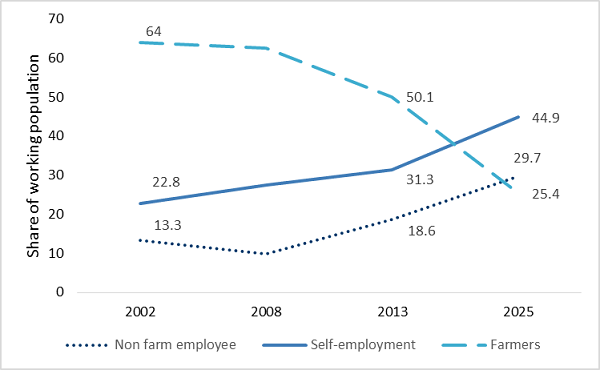

Successful emerging countries such as Malaysia and, more recently, India, have been able to provide quality jobs to their growing labor force by expanding fast and by encouraging their workers to move from low to high productive sectors. Cote d’Ivoire is following their lead. Since 2012, the country has become one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, with GDP rising by almost 50 percent in four years. Concurrently, the share of agriculture in total employment has fallen, while non-agricultural self-employment and wage employment have surged (see Figure 1). In 2025, at the current pace, agricultural employment will count for just 30 percent of total jobs, down from 64 percent in 2002 and 50 percent in 2014.

Job creation outside of the agriculture sector is good news. It should lead to higher income for most Ivoirians. Indeed, the labor income by a non-farm self-employed worker today is 60 percent higher than that of a farmer. The typical employee in a non-farm enterprise earns seven times more than an agricultural worker. Although there are big variations across individuals, such figures capture the unambiguously positive outcome of the structural transformation of the country’s labor market.

Figure 1: Ivoirians are moving out of jobs in agriculture

Source: World Bank

Yet, most new jobs will be created in self-employment and in household enterprises, with these two sectors expected to account for close to 10 million jobs by 2025. The problem is that these jobs are unlikely to provide decent incomes on a sustainable basis. Today, there are already many unsettled youths in the streets of Ivoirian cities, selling goods and services, mostly in informal or illegal trade. In spite of the rapid economic recovery, the average revenue associated with informal trade has declined by 15 percent in the last three years.

A roadmap for future job creation

So what can be done? The recently released World Bank Economic Update on Cote d’Ivoire proposes a roadmap. First, the government should provide support to the self-employed by encouraging their legitimacy or at least their recognition. As long as these workers remain illegal, it will be difficult for them to invest in their future. There is also a need to assist them financially, even if only modestly, and to facilitate their acquisition of basic competencies since few have completed post-primary education. International experiences indicate that programs integrating training (in technical and behavioral skills) and financial assistance are particularly successful, especially when they target young and female entrepreneurs.

Second, there needs to be an increase in wage employment opportunities. More hiring by formal enterprises will raise labor revenues. In that spirit, there is a need to accelerate the number of new registered enterprises since, in 2014, there were up to seven times proportionally fewer of these enterprises in Côte d’Ivoire than in Nigeria and Rwanda. Emphasis should be given to better access to external financing for small businesses and the streamlining of the business environment, including labor legislation. This effort should be accompanied by increasing technical and vocational education opportunities, because there is a strong positive correlation between a worker’s education level and the probability that they will be able to secure a wage job in an enterprise.

Third, amidst these changes, agricultural employment should not be forgotten. Indeed, if productive jobs cannot be found in rural areas, more workers will move to cities. Too many migrants will create tension in the urban labor market, which is already under pressure. In addition, an increase in agricultural labor productivity will boost the development of value chains, which are needed for creating quality jobs in Côte d’Ivoire. Increasing labor income in agriculture will require a shift from traditional to modern agriculture through further commercialization and diversification.

Implementing this triple strategy is not only important but urgent. Otherwise, Firmin and his friends will be unable to find decent jobs, raising their frustrations and the associated risks of social conflict in the country. Easier said than done, but those efforts are necessary if Côte d’Ivoire wants to fulfill its goal of becoming an emerging economy as fast as possible.

Commentary

The challenge of creating quality jobs in Côte d’Ivoire

December 17, 2015