Since Kenya introduced free primary schooling in 2003, the education sector at all levels has massively expanded. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, net enrollment rates in 2015 were the highest ever—74.6 percent for early childhood development and care, 88.4 percent for primary schools, and 47.8 percent for secondary schools. Further, public and private investments to the sector have grown massively: Today, it has the highest budget of any others, accounting for over 20 percent of the national budget, and over 6 percent of gross domestic product.

Nevertheless, more than one million children from 6 to 13 years old are still not in school, making this number the eighth highest of any country in the world. Education does not reach those who are marginalized, especially the pastoralist communities, those in remote rural areas, and the urban poor: In 2014, 580,921 boys and 711,754 girls (a total of 1,292,675) were not enrolled, either because they never attended school or dropped out. Of those that enroll, only 82.8 percent complete primary school.

With respect to girls’ education, the benefits and barriers have been widely documented. The latter include negative cultural practices like female genital mutilation; child, early, and forced marriages; severe poverty that prevents parents from paying school fees; continual migration due to prolonged droughts caused by climate change; poor health and nutrition; tasks associated with family care and housework; early pregnancies; school violence; travel involving long distances to school that are often unsafe; and lack of usable girls’ toilet facilities, among others. These barriers present complex socio-economic, cultural, political, environmental, and gender challenges that especially affect the educational opportunities of the most marginalized girls.

The role of mentoring in increasing attendance and completion rates

Based on current literature, it appears that mentoring helps pupils, especially girls, to achieve equitable and quality primary education as outlined in Sustainable Development Goal 4. Although it will not remove all the barriers to girls’ education, it can tackle some problems, such as female genital mutilation, early and forced marriages, early pregnancies, school violence, managing menstruation (while in school), risky sexual behavior, substance abuse, negative attitudes towards education, and weak peer, school, and family relationships. Once children are enrolled, a strong mentorship program can also help them acquire the 21st century skills needed to succeed in school and adulthood. It can also help increase attendance and completion rates.

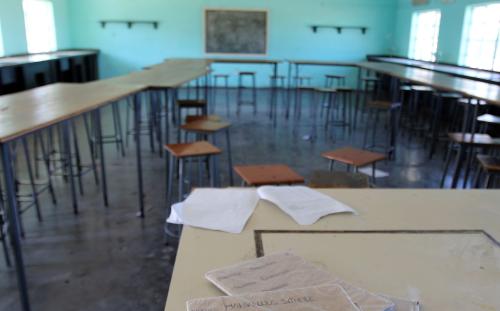

At present, a few schools have strong guidance, counseling and mentoring programs that are well structured and coordinated, and address many barriers; but, the mentoring curriculum is still poorly defined, and activities are ad hoc. Worse, most Kenyan schools do not yet have any such programs.

Thus, while at Brookings as an Echidna Global Scholar, I will evaluate a range of mentoring approaches currently being implemented in Kenya in order to determine which are the most promising in supporting the education of marginalized girls. The objectives are to (1) analyze current policies that support girls’ education, especially among pastoralist communities; (2) identify and document stakeholders’ best practices/strategies to support girls’ education; (3) propose a model girls’ mentorship program for Kenyan schools, and (4) help develop a policy and guidelines on mentorship programs. The study will include a desk review of current approaches and results, and consultations with various stakeholders.

To date, my study has focused on national data on access and retention in counties where 57 percent of the children who are not in school reside. These include Marsabit, Mandera, Tana River, Samburu, Wajir, West Pokot, Turkana, Garissa, Isiolo, Kwale, and Narok counties. Within these 11 counties, the study sampled the schools that had retention rates for both boys and girls that were higher than the national average (82.8 percent): This group totaled 68 primary schools, out of 1,799.

By selecting high-retention schools, the study sought to explore if and how mentoring programs have played a role in helping girls stay in school. If it is established that the programs are effective, it would be useful to determine the following:

- What challenges do mentoring programs address?

- What are the programs’ main components and structures?

- Does mentoring occur in school, out of school, or both?

- Who are the mentors?

- Do they volunteer or are they assigned?

Preliminary findings from my research indicate that the programs vary greatly, mainly due to the government’s lack of policies and models. The most popular include motivational talks, guidance, and counseling sessions by teachers to individual students or groups, peer-to-peer mentoring, leadership training, and spiritual guidance (schools invite religious leaders to talk to pupils). Most mentors are also teachers, but a few schools use community leaders and school alumni.

While at Brookings I will continue exploring mentoring programs in Kenya by looking at their components and structure in order to recommend policy guidelines and models that can improve education for girls from marginal communities and low-income households.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

One solution to several problems: How mentoring is changing girls’ education in Kenya

September 20, 2016