While teacher staffing and perceived shortages has become a hot button issue, less attention has been dedicated to another consequential staffing challenge in U.S. schools: school counselors. Despite the importance of school counselors, counselor staffing often lags optimal levels to adequately support student needs. School counselors often manage large caseloads of students, especially at schools that serve predominantly low-income and Black students, while taking on a wider range of responsibilities than “guidance” counselors of the past. The COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated the ever-expanding duties of school counselors, as they play a key role supporting students through pandemic-related trauma.

In this post, we review the state of school counselor staffing, evidence on counselor staffing on student outcomes, and the implementation of policies aimed at reducing counselor caseloads. We close by considering who school counselors are–and the implications for student outcomes.

Research shows counselors positively affect student outcomes

A growing consensus points to consistent positive impacts of school counseling programs, and specifically the positive impacts of increasing counselor staffing, on elementary-aged children’s behavioral and academic outcomes. A nascent body of work also finds positive effects of school counselors on secondary student outcomes. One study found that when states mandate that schools hire an additional high school counselor, the share of students going to a four-year college increases by 10 percentage points. Other research, leveraging the quasi-random assignment of students to counselors based on last name, finds that being assigned to a higher value-add school counselor increases the likelihood of students graduating high school and enrolling in college by about two percentage points, with larger effects for low-achieving and low-income students. A recent analysis by the Department of Education mirrors these studies, finding students who met with their school counselor in high school were much more likely to apply for and receive financial aid, with an especially strong relationship for students whose parents did not attend college.

The landscape of state school counselor staffing policies

Despite a growing research consensus that counselors matter, we still know comparatively little about the distribution of counseling across schools and students, and what policies drive students’ access to quality counselors. To examine the national high school counselor landscape, we leverage the 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection and data from the American School Counselor Association (ACSA) on state counselor staffing policies to outline the landscape of counselor policies in theory and in practice.

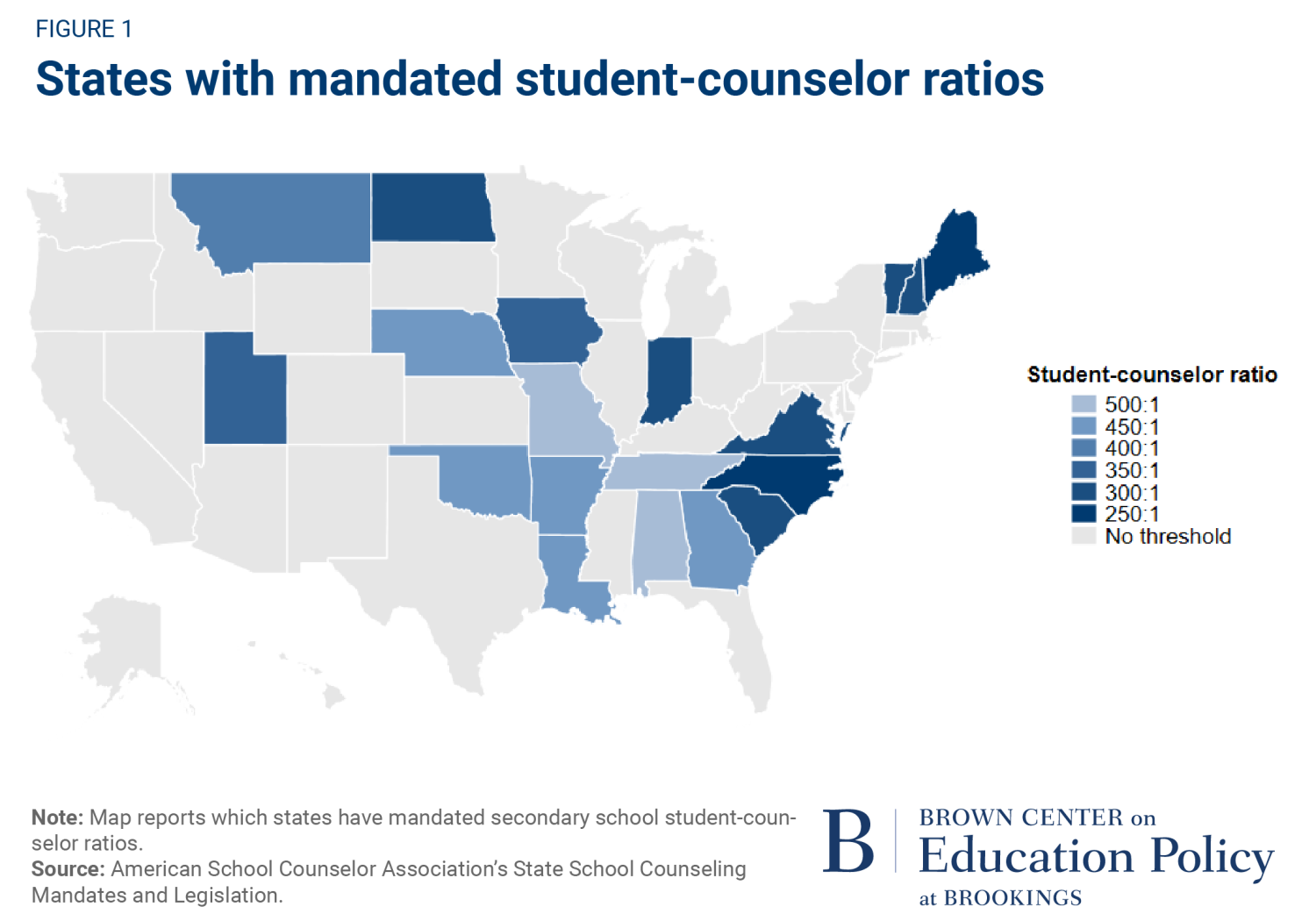

There are several state policies that target counselor access. According to data from the American School Counselor Association, 23 states mandate school counseling in elementary schools while 30 states mandate counseling for secondary school students. Another 19 states target a specific student-to-counselor ratio–for example, Oklahoma mandates that schools employ one counselor for every 450 secondary school students. As illustrated in Figure 1, the prevalence of these policies varies by region. States in the South are more likely to have policies mandating school counselor staffing, though schools in the Northeast tend to mandate the smallest ratios. The modal ratio is a 300:1 ratio, though states set target counselor caseloads from 250 students to 500 students per counselor.

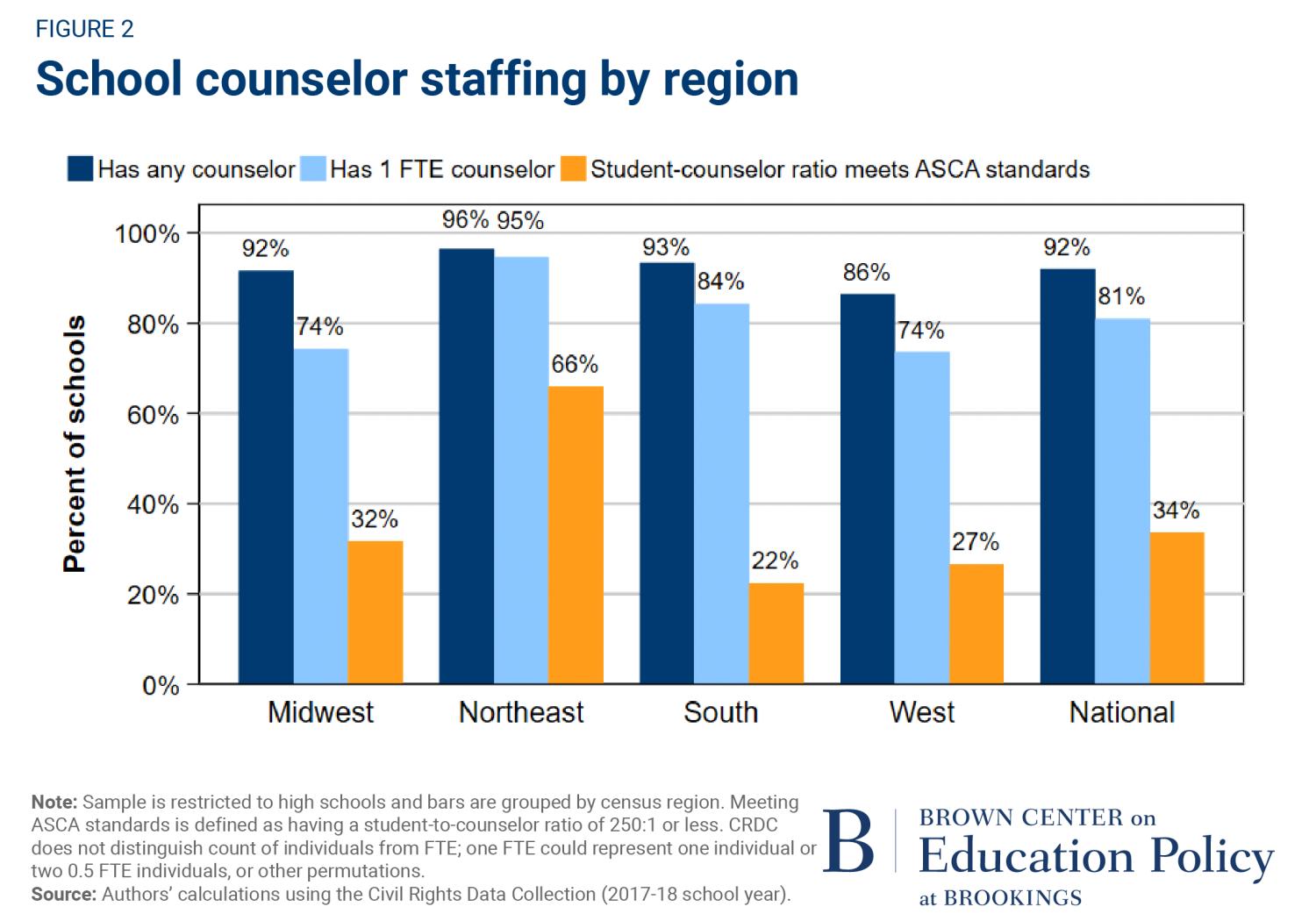

We then examined how these policies–and the regional patterns observed in state policies–relate to actual counseling rates. First, as displayed in Figure 2, we observe that across the nation, nearly all high schools have at least some counseling available. Overall, 92% of high schools in our sample have some counseling. We also observed substantial regional variation. Fewer schools have a full-time counselor (or full-time equivalent), ranging from 86% of high schools in the West to 96% of schools in the Northeast. Far fewer schools meet the ASCA recommendation of a 250:1 student-counselor ratio–while 66% of high schools in the Northeast maintain a 250:1 or lower student-counselor ratio, only 22% of schools in the South, 27% of schools in the West, and 32% of schools in the Midwest meet or exceed the ASCA standard. Across regions, the average secondary school student-counselor ratio is substantially higher than the ASCA standard (approximately 320:1).

The implementation of counselor staffing policies

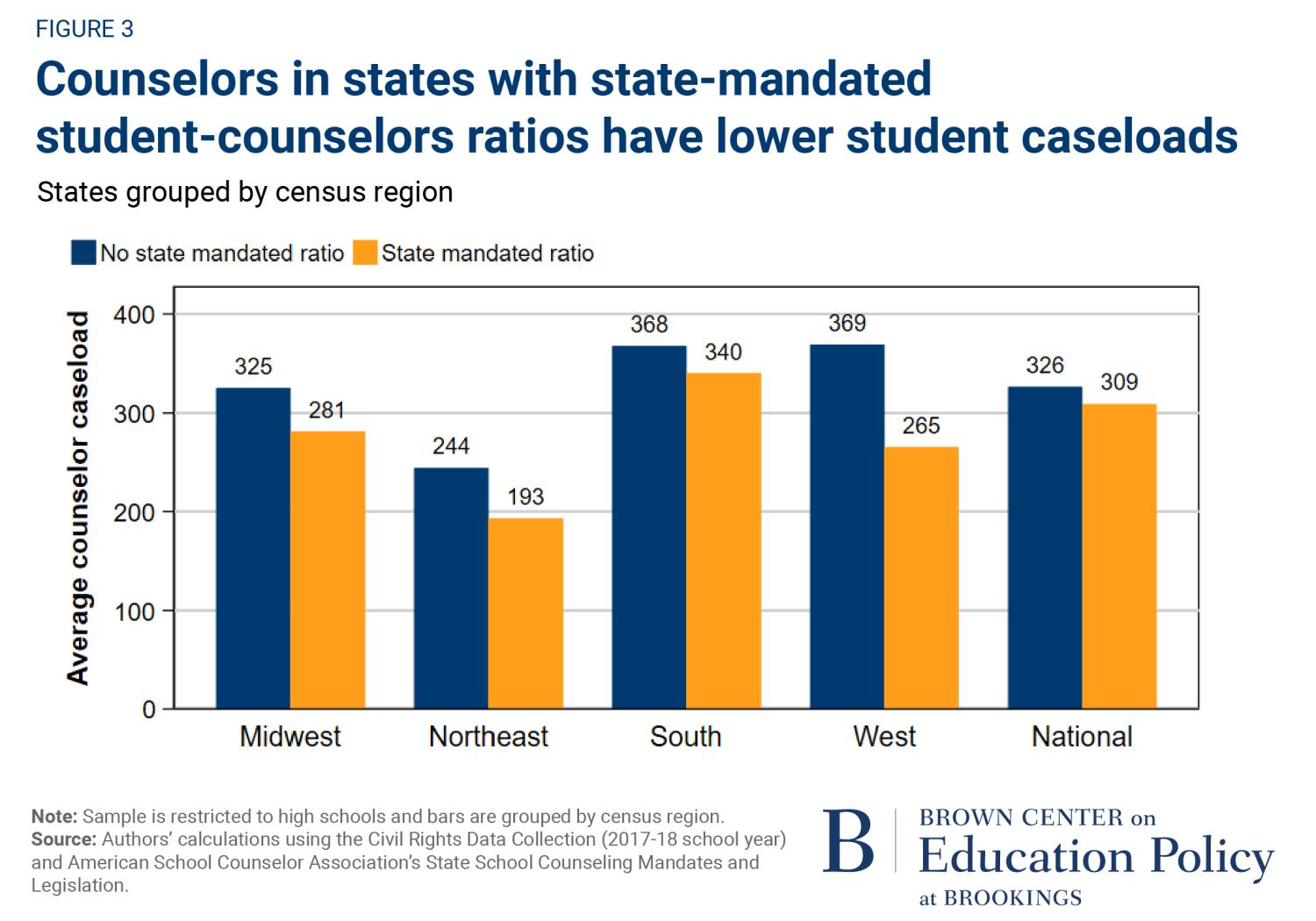

It is one thing for a state to mandate a certain student-counselor ratio, but how do those policies relate to counseling levels? In Figure 3, we show that high schools in states with mandatory counselor-student ratio policies have significantly lower student-counselor ratios than states within the region without mandated ratio policies in place. For example, in the West, counselors in states that mandate a student-counselor ratio have an average of 100 fewer students in their caseload.

School counselors in practice: Counselor workload and demographics

Even if schools comply with state policies, how they do so likely matters, too. Here, we use a rich publicly available dataset of Oklahoma school staffing data merged with CRDC data to examine counselor characteristics. Only 67% of counselors in the state work full time in one school. Other counselors either split their time across multiple schools or across multiple jobs; we find 10% of counselors are also teachers, and 22% of all counselors are assigned to multiple schools (often to both a high school and middle school or high school and elementary school in the district). In some severely understaffed rural schools in Oklahoma, counselors report taking on multiple jobs, including even superintendent and cafeteria worker. Even if schools meet a state FTE requirement, they may do so by piecing together time from existing staff, potentially spreading school support staff too thin to sufficiently serve all students.

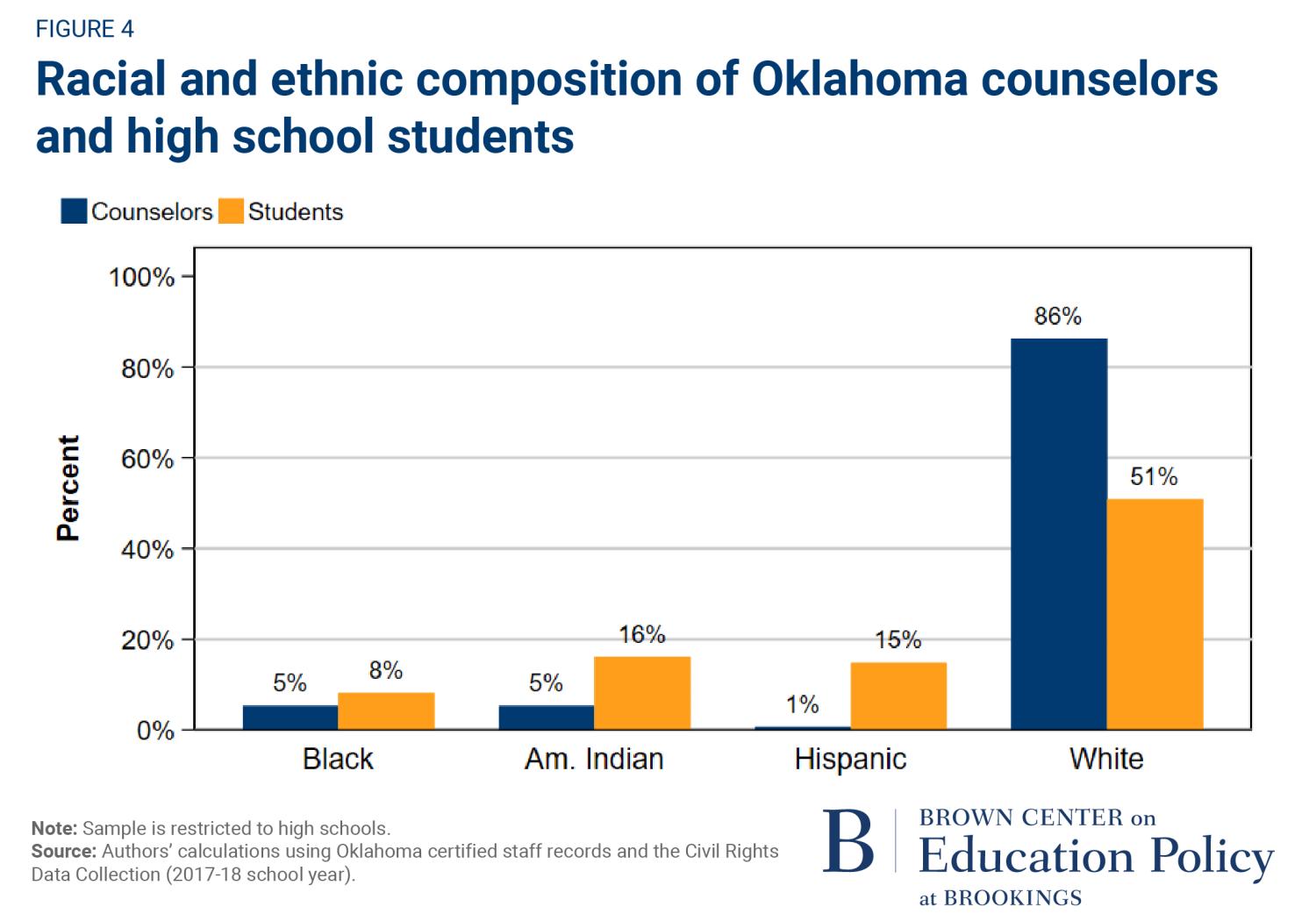

We also find large gaps between high school student and counselor race. Numerous studies in education and public management show that racial representation in positions of authority and mentorship benefit students but that teachers and principals rarely reflect the demographics of the students they serve. Here we find the same for counselors. In Figure 4 we show that on average 16% of Oklahoma high schoolers are American Indian/Native, relative to 5% of Oklahoma counselors. While about 15% of Oklahoma high school students are Hispanic, less than 1% of counselors are. Nationally, 76% of ASCA members are white compared with 51% of school-aged children, while 6% of ASCA counselors are Hispanic compared with 25% of school-aged children; while there are fewer Black counselors than students, the gap is smaller, with Black counselors comprising 11% of the profession relative to Black students representing 14% of the school-aged population.

Who counselors are and how they view their role has important implications for student outcomes. Counselors are not immune from bias found across school professionals and society, with one experiment finding counselors were less likely to recommend Black female students for advanced math courses even relative to student profiles with weaker academic and behavioral records. Another experiment found similar patterns–counselors were less likely to recommend a student with low academic preparation pursue community college if that student was identified as Black. Another analysis of school counselors in Oklahoma found counselors varied in whether they perceived their role as “school support official” or “compliance officer”–and that counselors who viewed their role as support-oriented were more likely to meet with parents and proactively inform students of scholarship eligibility.

As we show, many states implement policies targeting counselor staffing levels, and states that have made that commitment tend to have lower counselor caseloads. But adding more counselors is likely necessary but not sufficient. Investments in increased staffing should be paired with evidence-based professional development and a commitment to hiring more full-time counselors to ensure counselors have the tools and capacity necessary to support all students as they navigate high school and beyond.

Methodological notes: Civil Rights Data Collection 2017-2018 administration analyses conducted by authors using publicly available school-level files. Analysis limited to schools enrolling 9th grade students, and does not include juvenile justice facilities, magnet schools, charter schools, special-education schools, or alternative schools (total sample is 16,978 schools). State policy analyses conducted by authors using publicly available reports from the American School Counselor Association (ASCA). Oklahoma staffing analyses conducted by authors using publicly available individual-level files, merged with CRDC data (total sample is 300 schools).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).