Over the past decade, “nudging” has gone from novel concept to standard practice across many higher education institutions. What can we say about whether–and when–nudging works and should be deployed to improve student outcomes?

What is a nudge?

“Nudging” refers to a wide set of interventions that guide, rather than mandate, individuals to act in a certain way. Generally, nudging encourages actions that will benefit individuals (such as increasing retirement investing) or benefit society at no meaningful cost to individuals (such as increasing blood donations). Importantly, nudges always provide an individual the chance not to do an encouraged action. Brightly colored arrows painted on the ground leading commuters to take the stairs instead of the escalator constitutes a nudge–shutting off the escalator does not. “Nudging” encompasses many design choices, such as changing the default (e.g., changing the default loan amount offered to community college students) or providing an anchor (e.g., noting how much most students borrow). In many cases, the question is not whether to nudge but how–what default loan to offer students or what order to list schools in a school choice brochure.

A common nudge strategy in education has been to send targeted information to students and families–about how to enroll in early childhood programs, encouraging school attendance, and supporting college attendance. These interventions have expanded in recent years, with numerous randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of nudging approaches. The field has now reached a point of maturity where we can consider what works in nudging and what open questions remain to be explored.

When should nudges be used?

While nudges can be effective strategies to change behavior, they are not appropriate for all policy goals. The following questions are essential for considering whether to deploy a nudge intervention:

- Is there an intention–action gap? Do we believe that individuals want to (or could be persuaded to want to) pursue the nudged activity? If yes, this is a good candidate for nudging.

- Is the barrier to completion structural? If yes, nudging may not be enough to overcome these structural challenges. Consider a student who wants to attend class regularly but has persistent transportation issues. A nudge campaign could encourage the student to review the bus schedule and make a plan to arrive to class on time–but only if a sufficient transit system exists to take students from their home to campus. Nudges have limited effectiveness in these cases.

- Is the source of inaction clearly identified? If yes, customize nudges to students’ specific needs and reasons for inaction. Students who don’t know about a task need different messages than students who know about a task but don’t know how to complete it.

Do informational nudges work?

Informational nudges have dominated behavioral science applications focused on college access and success, with a deep literature base examining how different strategies affect college attainment. The college transition is a challenging time when informational nudges can be particularly effective, as students adapt to life without parental or school-based support and structure for managing tasks. Once in college, students must learn to juggle the new demands of academics and administrative requirements, often alongside work and family responsibilities, and delivering key information in a timely way can help connect students to resources or meet important deadlines. Students can receive these informational nudge campaigns across all media platforms–but in recent years, text-based outreach has become a common communication medium, starting as standard SMS messages and evolving into more complex messaging systems integrating images and smart response logic.

While many of these text-based informational nudges show promising effects in local implementation, efforts to replicate and scale to larger populations often have yielded disappointing results. This phenomenon is hardly limited to nudge efforts. Nevertheless, we consider here what we can learn from variation in the success of these efforts at scale. Take, for example, the case of refiling the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). Some 15-20% of Pell grant-eligible students don’t re-submit the FAFSA. This is a clear intention-action gap where nudges can be effective–students should want to maintain their federal aid but face barriers to completing the form. Researchers successfully partnered with a non-profit to send informational nudges about FAFSA resubmission to college freshmen; as a result, community college freshmen were 14 percentage points more likely to remain continuously enrolled into their sophomore year. In this intervention, students who received these messages had worked with the non-profit when they were high school students. Students actively engaged with the messaging and only 5% of students opted out from messaging.

Researchers tested scaling up this strategy with a national sample of about 10,000 college students who received similar informational nudges about FAFSA re-filing, though sent from a non-profit with whom they had no prior relationship. Unlike the experiment where students were familiar with the advisors sending nudges, about 25% of students opted out from messaging in the national campaign, and it had no overall effect on FAFSA filing (though some students filed earlier), federal financial aid receipt, or college persistence. Other efforts to scale up FAFSA reminders to high school students, like sending messages on behalf of the Common Application, similarly had no effect on aid receipt or college enrollment. The authors of both studies reason that local implementation may be an essential feature of informational nudge campaigns. Students may not take up guidance or respond to information from sources they do not know and trust.

How are successful nudges designed?

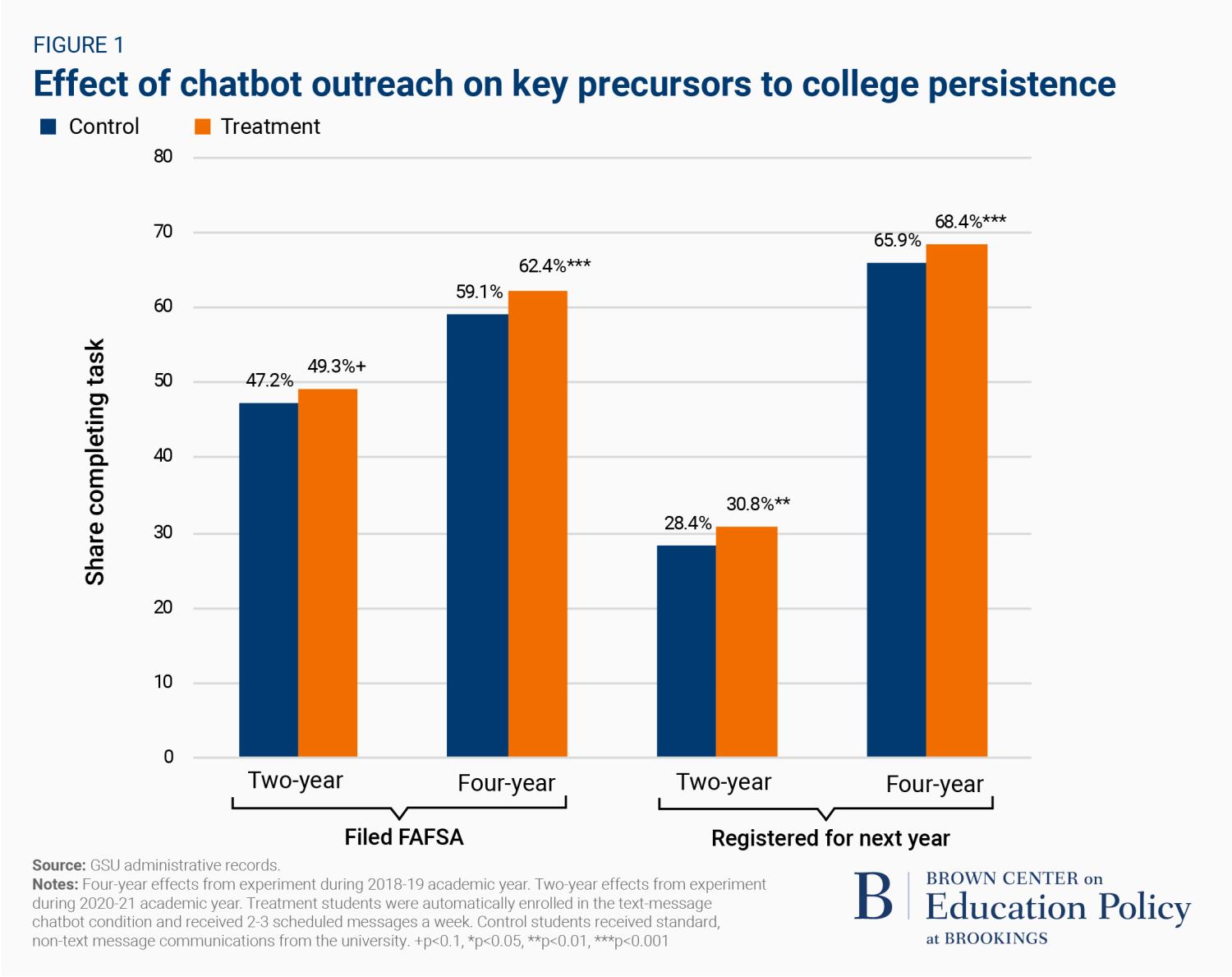

In recent joint work with colleagues Jeonghyun Lee and Hunter Gehlbach, we tested the implementation of a text message “chatbot” to support students after college enrollment at Georgia State University (GSU). The chatbot deployed a combination of text-based informational nudges, AI-powered responses to student questions, and staff intervention when the bot was unable to address a question. The chatbot was set up to answer direct questions such as “when does registration open” or to send resources in response to statements such as “I got dropped from classes because I have a balance due” (replying, for example, with a link and phone number for the financial aid office). A prior implementation of the chatbot helped reduce summer melt among students admitted to GSU by about three percentage points. In this new study, we examined whether the same communication tool could boost student persistence and retention. Importantly, we tested the chatbot with both associate degree-intending and bachelor’s degree-intending students within the GSU system to examine whether the strategy could scale across different contexts and student populations.

We found consistent positive effects on key predictors of persistence–filing the FAFSA and registering for the next term. In many instances, the chatbot encouraged students to complete these tasks earlier in the semester. This is important since filing financial aid forms earlier in the year may result in students receiving more aid (or having more time to navigate the complex FAFSA verification process).

GSU’s successful use of a chatbot to support enrolled students shares an important commonality with prior successful nudge efforts in that students were familiar with the sender–in this case, their college. Even so, not all messages affected student behavior. Mirroring best practices in nudging, the most impactful messages in the chatbot campaigns were ones that:

- Focused on acute tasks: Messages about tasks that were serious and time-sensitive, such as resolving an outstanding balance on a semester bill or addressing an academic hold, had greater impact.

- Included actionable next steps: The best-designed messages included the “what” (“looks like you have a balance hold on your account”), the consequence (“this will stop you from registering for summer & fall”), and a call to action (“You can take care of this hold through your account. For questions, email X”).

- Targeted students’ specific needs: Using administrative records, GSU targeted messages to students for whom the content was most relevant. That meant not everyone got a reminder to file the FAFSA–only students who had not yet filed their FAFSA did. This decreased the number of messages sent and increased the relevance of the messages students received.

What’s next?

Nudges offer a low-cost option to support students through proactive outreach and may be especially beneficial at institutions enrolling large shares of students most in need of additional support. However, one commonly cited concern about nudging is that they remove the sense of urgency to invest in larger-scale support systems. Nudging should never be a substitute for larger investments, such as increasing financial aid or hiring more student advisors. But nudges can still play a valuable role as a complement to these investments, informing students about and encouraging them to take advantage of additional supports.

Targeted informational nudges will likely continue to be a part of the standard student support toolkit in the coming years as higher education administrators face ongoing challenges supporting college completion for ever-evolving student populations who face confusing financial aid, matriculation, and persistence processes. Informational nudges that focus on the most acute challenges students face, target communication to students’ specific needs, provide students with engagement opportunities, and build on a foundation of trust and familiarity have the best potential to support students.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).