David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, asked “What’s the smartest response from Congress and the president to the uncomfortable fact that today’s projections about future budget trends are surely going to be off?” He was introducing the subject of a recent Hutchins Center event and set of papers designed to help answer that question. In one of the papers, Alan Auerbach—a professor of economics and law at the University of California, Berkeley—argues that the appropriate response to fiscal uncertainty is to take more action now as a precautionary measure against the possibility of worse-than-expected outcomes. He explained during the event that “if the future is uncertain, there is a case for saving, as a form of self-insurance.”

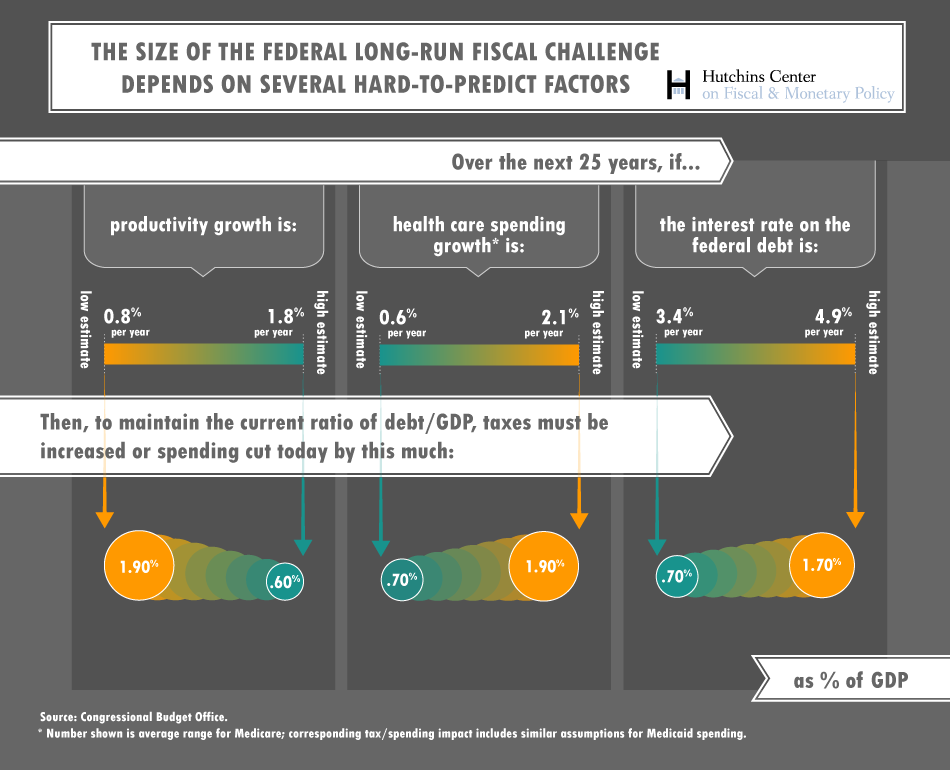

The graphic below reflects the difficulty of predicting the fiscal future by isolating three major sources of fiscal uncertainty over the next 25 years: the rate of productivity growth, the rate of health care spending growth, and the interest rate on the federal debt, and showing the actions we would have to take today to keep the current ratio of debt to GDP for both high and low outcomes of those three factors.

“Whether these factors move in a favorable or unfavorable direction,” Auerbach writes, “will determine the nature and extent of the fiscal response needed for stabilizing the national debt as a share of GDP.” For example, if all three factors move in a favorable direction (i.e., high productivity growth, low health care spending growth, low estimate of interest rate on the federal debt), then, Auerbach notes, no federal response is needed today to stabilize national debt as a share of GDP. However, if productivity growth is at the low estimate, then taxes must be increased or spending cut today by 1.9 percent to maintain the current debt-to-GDP ratio. Auerbach argues that the government should cut spending and/or raise taxes sufficiently to reduce deficits to acceptable levels—and then should do more belt-tightening to compensate for uncertainty.

Auerbach proposes three ways to more effectively convey this uncertainty: requiring the Congressional Budget Office (CB) to include in its forecasts a quantitative assessment of the degree of uncertainty; subjecting the government to a “stress test” to gauge its ability to respond if unfavorable circumstances arise; and the use of automatic adjustments to provide budget stability and risk-sharing across generations.

“What is clear,” Auerbach argues, “is that hoping for a better future does not constitute an appropriate policy response to uncertainty, and waiting until the size of the problem is known is waiting too long.”

Visit the event’s page to get video, transcripts, and presentations from admirers and critics of the Auerbach approach, as well as two other working papers that were discussed and presentations by the director of the CBO and his British counterpart.

- “In Good Times and Bad: Designing Legislation That Responds to Fiscal Uncertainty” by David Kamin (pdf)

- “The Economics and Politics of Long-term Budget Projects” by Henry Aaron (pdf)

Also, see Nobel Laureate Peter Diamond’s response to Auerbach’s paper (pdf), and David Wessel’s summary review of the event.

Commentary

CHART: The Sources of Fiscal Uncertainty

December 22, 2014