There are issues with housing and other kinds of stuff, but our tourism economy is one of the primary drivers of economic development and it’s homegrown development. We have small business owners who are building their families and growing their lives here. But it’s been so long and such a hard fight, and then all of a sudden it feels like this is gonna kick the legs out from the stool from everything that’s already here.

Tucker United member

When a permit application for a proposed power plant heralded the possibility of a large data center being located near the towns of Davis and Thomas in West Virginia, local leaders and residents were taken by surprise and are determined to protect the creative economy and natural beauty of their place. In this episode, host Tony Pipa revisits Tucker County to capture the story of a community at the intersection of national technology policy and local control.

Featuring:

- Nikki Forrester, Co-publisher and designer, Highland Outdoors

- Heather Hannah, Musician

- Dan Parks, Publisher, Country Roads News

- Walt Ranalli, Co-Owner, Siranni’s Pizza Cafe, Davis, West Virginia

- Alan Tomson, Mayor, City of Davis, West Virginia

- Kimberly Joy Trathan, Founder, Gradient; former city recorder, Thomas, West Virginia

Want to learn more? See Tony’s interview with Brookings Senior Fellow Nicol Turner Lee on the global race for AI, local impacts and trade-offs, and community oversight.

Listen below to Nikki Forrester reading her editor’s note in “Highland Outdoors” (Fall 2025).

Additional notes:

- The song heard at the start and near the end of this episode is “Faultlines,” written and performed by Heather Hannah.

- The recording of Senator Randy Smith occurred at Tucker County Senior Center, Parsons, WV, and is courtesy of Country Roads News.

- The poster-making and tree-decorating event audio comes from an event in downtown Thomas on November 16.

- The archival recording about the CCC comes from a West Virginia Public Television documentary featuring archival material from the National Archives and Records Administration.

Transcript

[music]

PIPA: There’s always something to see — and hear — at The Purple Fiddle. The music venue is an institution here in Thomas, West Virginia. There’s an act on stage every weekend of the year, and my visit last month was no exception.

[music]

PIPA: During my very first season of Reimagine Rural in 2023, I came here to chart the journey of Thomas and Davis, its sister town situated a few miles down the road. After the loss of the region’s coal and timber industries, a new economy emerged here based in the arts and outdoor recreation. The Purple Fiddle was a catalyst in that renewal, helping attract new residents to the region who played an important role in revitalizing these downtowns with studios, galleries, restaurants, and shops.

[music]

Back then, the local leaders and business owners I talked to felt as if they, and others before them, had made enormous progress in bringing the downtowns back to life. And what concerned them most was protecting what made the area distinct and exceptional. Everyone was also talking about the construction of the last stretch of a 150-mile highway expansion project, first started more than 50 years ago.

That buildout had made getting to parts of West Virginia much easier. But a pending decision on where to locate a remaining portion of the four-lane road had become controversial, because the state had it set to cut right between Thomas and Davis. Here’s Kimberly Joy Trathan, who was on the Thomas town council at the time, and Walt Ranalli, a former mayor of Thomas who co-owns a beloved local restaurant in Davis.

[2:02]

TRATHEN: We’re so close, and our communities overlap in such ways. Like, is it going to divide the communities or is it going to like, you know, is it gonna become so easy for people to come here that we might not have the ability to sustainably deal with it? I think that’s a little bit more my concern of just like, are we gonna get overrun?

RANALLI: That road can be a magnificent, it has been a magnificent help to this region, to business in this region, and to the development of this region, but it can also be the detriment of x.

PIPA: Two and a half years later, that decision is still unresolved. But a new issue has cropped up in the meantime and eclipsed all the chatter about that highway — a proposed industrial development that reflects what’s happening across much of rural America: a big power plant that would serve what appears to be a data center, to be located right here in Tucker County.

Why are proposals for data centers showing up in rural places? Well, the major technology companies in the U.S. are in a race amongst themselves and countries such as China to develop artificial intelligence. The AI revolution needs lots of computing power. That means warehouses full of cutting edge computers. And those places need large amounts of land, water, and power — which you can often find in abundance in rural America.

For local rural leaders and residents interested in economic development, a data center can look like an opportunity. For others, it can look like a scourge.

HANNAH: You can find a data center about anywhere that you want to find a data center, pretty much. There’s nothing really special about that. But there is something incredibly special about the fact that the headwaters of the Potomac are right here. This is where rivers come from. There’s so much here to protect.

[music]

PIPA: I’m Tony Pipa, a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution, and your host for the Reimagine Rural podcast, where I capture the stories of rural places across America that are aiming to thrive amid economic and social change.

As we near the close of this third season of the podcast, I’ve decided to check back in with some of the towns I’ve already profiled, to learn how things have gone since I visited last. After all, communities are dynamic places, and change is rarely a linear process.

Thomas and Davis sit about 170 miles west of Washington, D.C. Thomas was a coal town, home to what was once one of the largest coal companies in the world. Davis had a thriving timber industry. And the railroad connected West Virginia to the world.

After Blackwater Falls State Park was established in 1937, members of the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal work relief program, helped to plant thousands of seedlings there. Fires had razed forests in West Virginia, and soil erosion was rampant during the Great Depression.

[5:23]

ARCHIVAL: “Mountainous West Virginia is a land of valuable natural resources and pleasant scenic beauty. Into West Virginia’s mountains within the last few years has gone a new force, the Civilian Conservation Corps, to make this recreation resource available to all people.

“Since the Conservation Corps went into the parks, much has been done. Roads, bridges, cabins, lodges, and dams have been constructed, and precaution has been taken to see that natural beauty is not spoiled.”

PIPA: The coal and timber industries began a steady decline in the years to come, and after a hundred years in operation, the railroad quit running in the early ‘80s. As we learned in our earlier episode, the change to the art and outdoor recreation scene began to take shape in the late ‘90s.

To understand some of the local people’s reaction of the proposed power plant here, it’s worth taking a little time to understand the place.

[6:23]

HANNAH: I was born in the coal fields and spent the first 20 years of my life there. Southern West Virginia informed who I am, and Tucker County equipped me with the ability to express that.

PIPA: That’s Heather Hannah.

HANNAH: I’m a mother. I’m a mountaineer. I’m a musician. A maker. And it has been such a wild gift to get to spend the last 20 years of my life here in Thomas.

PIPA: Heather describes Thomas as the rare place that affords visitors the opportunity and space to explore some of life’s big questions. Someplace authentic, where you can get a little closer to your higher self, in a way that doesn’t wear off when the vacation’s over.

[7:21]

HANNAH: We want our time to mean something. And that means moving your life into alignment, even if it’s just for a weekend. Because now you know how it sounds. Now you know how it feels. Now you know what it looks like.

PIPA: And for residents? They have become the anchors in transforming these downtowns — many of them artists who display their work in shops and galleries that line the main street. Poets. Musicians.

[music: “Faultlines” by Heather Hannah]

HANNAH: There’s room. There’s room for the wheel of inspiration into expression to turn. There’s support here. There’s support for ideas. There’s cooperation. That’s part of what has made Thomas so successful.

PIPA: And what else is so distinctive about this place is the combination of that creativity with the nature that surrounds it. This is Nikki Forrester, a science writer and ecology and evolutionary biologist, who, with her husband, runs a quarterly magazine devoted to outdoor recreation in West Virginia.

[8:37]

FORRESTER: I mean, the biggest draw for me has always been the proximity to just getting outside. Like, I love the forest here. I love the red spruce forest. It’s such a unique place in really the whole country. There’s not many other high elevation valleys like Canaan Valley, and there aren’t many places that I’ve found that are quite like West Virginia.

And so being able to just leave from my door and go for a bike ride or a hike, and spend time in the woods, and see the stars at night, and the quiet just really speaks to me, and I feel like has been a huge reason why I fell in love with this place and why I want to stay here for the rest of my life.

It’s just such a special place to me.

PIPA: This part of West Virginia is one of the most visited destinations in the entire state. It draws leaf-peepers from across the eastern United States every fall, cross-country and downhill skiers in the winter. One of my favorite views is at Blackwater Falls State Park — facing away from the water, actually. The way the sunlight breaks through the trees alongside the staircase trail built right into the side of the mountain — it’s just stunning.

That beauty, and the ready access to the outdoors, is what drew journalist Dan Parks here from Washington, D.C. — first to visit, and finally to stay.

[10:04]

PARKS: I’ve been coming here for about 20 years. It was already in transition from an extraction-based economy, timber and coal, to a tourism-based economy. And that’s why I started coming out here, frankly, was to camp, and hike, and bike, and ski. It’s moving even more in that direction in terms of the dependence on the tourism-based industry.

PIPA: Tourism is the main economic driver here now, but that hasn’t been without controversy. It’s created a new version of the absentee landownership prominent in West Virginia: residents from out-of-town or nearby states buying second homes, edging out locals and driving up prices. The short-term rental market exploded in recent years, even prompting some leaders in Tucker County to try to put a cap on Airbnbs and VRBOs.

The service industry has grown to meet the influx of tourists, but those jobs don’t always pay well. We talked to people here who juggle multiple jobs at once. The coffee shop in Thomas acknowledged as much when they raised prices earlier this year, explaining the importance of paying their employees a living wage.

And while data centers generally don’t create many permanent jobs, they can stimulate a workforce while the construction is underway — and that can be an attractive prospect for some people.

[11:26]

PARKS: There seems to be a lot of suspicions sometimes between folks who have been here for generations and those who have moved here recently or just visit here. And there’s a feeling sometimes that the people who are coming here just to visit or who have second homes here really just don’t care about the people who have lived here for generations and who have worked in areas other than tourism.

And there’s a feeling that the people who like to bike and ski and do those sorts of things really don’t have much sympathy for those who are struggling to make a living here, who grew up with other industries, who might not want to work at the ski hill, who might not want to be a restaurant server. And that there’s a lack of interest in the kinds of economic development that would help out those folks.

PIPA: Dan started a Substack called “Country Roads News” about two years ago that focuses on hyperlocal, hard news: city council, county commission, utility issues — stories with broad appeal.

[12:31]

PARKS: So it’s a mix of locals who live here and tourists who visit here regularly. We get about a million tourists a year in this area.

[music]

And the stories that I cover, I really try to hit that sweet spot, in terms of appealing to both audiences.

PIPA: Earlier this year, a local environmentalist spotted a legal notice in a local paper — something vague, a permit request. The company, Fundamental Data, was seeking an air quality permit from the state of West Virginia for a 1,500-megawatt power plant near Thomas and Davis.

[13:08]

PARKS: There was a lot of speculation initially about the purpose of that power plant and the people who applied for that permit weren’t saying why they wanted to build such a large power plant. In subsequent hearings and venues, it’s become clear that the purpose of that would likely to be to power some kind of a data center complex.

There’s no indication that this power would be used to help the communities of Davis or Thomas in terms of providing electricity for them. Local officials were unaware this was happening until the permit application was filed. So the purpose really seems to be for something else.

And we don’t know if that would be for artificial intelligence or Bitcoin mining. We just don’t know. Right now, all we know is that there’s an entity incorporated in Delaware, where it’s almost impossible to learn about who might really be behind this project, that wants to build a large power plant very close to the towns of Davis and Thomas.

[14:00]

TOMSON: I was sitting in this office in late March and I received a phone call from a conservation group. They asked me if I knew about the proposed power plant. And I said no. I had not heard of it at all.

PIPA: This is Alan Tomson, a retired career Army officer and now the mayor of Davis.

TOMSON: So that started the questioning. And then when I was asked about it and I didn’t know about it, I called the mayor of the City of Thomas and asked if he knew about it, and he said he also hadn’t heard anything. Then I called the president of the county commission and asked the same question. He said he had not heard of it. And I called the executive director for the economic development authority, and he had also not heard of it.

So nobody in the local area, had any indication that there was a power plant being thought of and that an air quality permit was submitted. So we were all kind of blindsided by that initiative starting to take form.

PIPA: Dan broke the story on his news site.

[15:05]

PARKS: That went off like a bomb in the community. People were shellshocked by it.

TOMSON: In early April, I convened a town hall meeting. And it was probably the largest attended town hall meeting in the history of Davis. We used the Fire Hall, which had a capacity of 300 people. We were standing room only. And we had a video conference set up, which maxed out at a hundred people. So over 400 people attended that town hall meeting where we started to lay out the facts as we could discern them from a heavily redacted air quality permit.

Davis has a population of about a thousand people. So we had a a considerable showing from people in Davis, but it was also attended by people that live in Canaan Valley and also the City of Thomas because at that point, everybody wanted to know what the heck was going on.

PIPA: Kimberly Joy Trathan, the local artist and gallery owner who had served on Thomas city council until just recently, was shaken.

[16:08]

TRATHAN: I heard first about it back in March from a friend who made a passing comment, something about how, what’s this place gonna be like when the data center moves in? And I was like, What data center? Sometimes you hear a lot of things in small towns, you think it’s a rumor, you know, somebody heard something and it turned into something bigger. So it had just really been sprung on everyone around the same time. So it was deeply disturbing, still is deeply disturbing.

PIPA: Walt Ranalli thought he’d seen it all by now. He opened Sirianni’s Pizza in the late 1980s, just before the local extractive economy crashed, and was the mayor of Thomas in the 1990s. I first interviewed him in 2022, and we got to catch up again on my recent visit.

[16:58]

RANALLI: Wait a minute, what are y’all doing? Again you’re just, you know, using us like a colonial state. I’m going, we were all sort of shocked that they proposed it right between the two towns, and I can see them proposing it here, but right there? It could be out 93, that’s 15 miles of wilderness, which I’d hate to see, but I mean, they should have been, they weren’t planning or thinking, you know, there can’t be some kind of mega industrial site right there between us.

FORRESTER: And there was just this upwelling of concern from people who lived in Davis and Thomas and Tucker County about what is this project?

PIPA: Science writer Nikki Forrester again.

FORRESTER: How is it gonna impact us? Who is this company? Why don’t we know anything about it? And at that meeting, my friend stood up and said, Hey, if we really want to do something about this, we’re gonna have to get organized.

PIPA: The group that came to be known as Tucker United formed the next day. Nikki is also their communications director.

[17:58]

FORRESTER: I think we have about 400 people on our mailing list now. So I’d say as the days go by, we’re just doing our best to keep moving forward, fighting this proposal, and then also thinking longer term about economic development in Tucker County and just growing a broad coalition so that everyone here has a voice and a say and can be heard and represented when it comes to shaping the future of what Tucker County’s going to look like.

PIPA: So let’s get into some specifics here. The power plant, as outlined in the permit request, is set to operate primarily on natural gas. It doesn’t appear it will be connected to the electric grid — meaning what it is powering must be close by.

[18:46]

PARKS: So the use would have to be on site presumably to some sort of a user that would be in close proximity to the facility. It’s important for data centers to have an uninterrupted power supply. It can cause all kinds of problems for them if power is interrupted for even a second. So this particular power plant would operate primarily on natural gas, but it would also have a backup fuel source of diesel to run in the event that there’s some sort of an interruption in the natural gas supply.

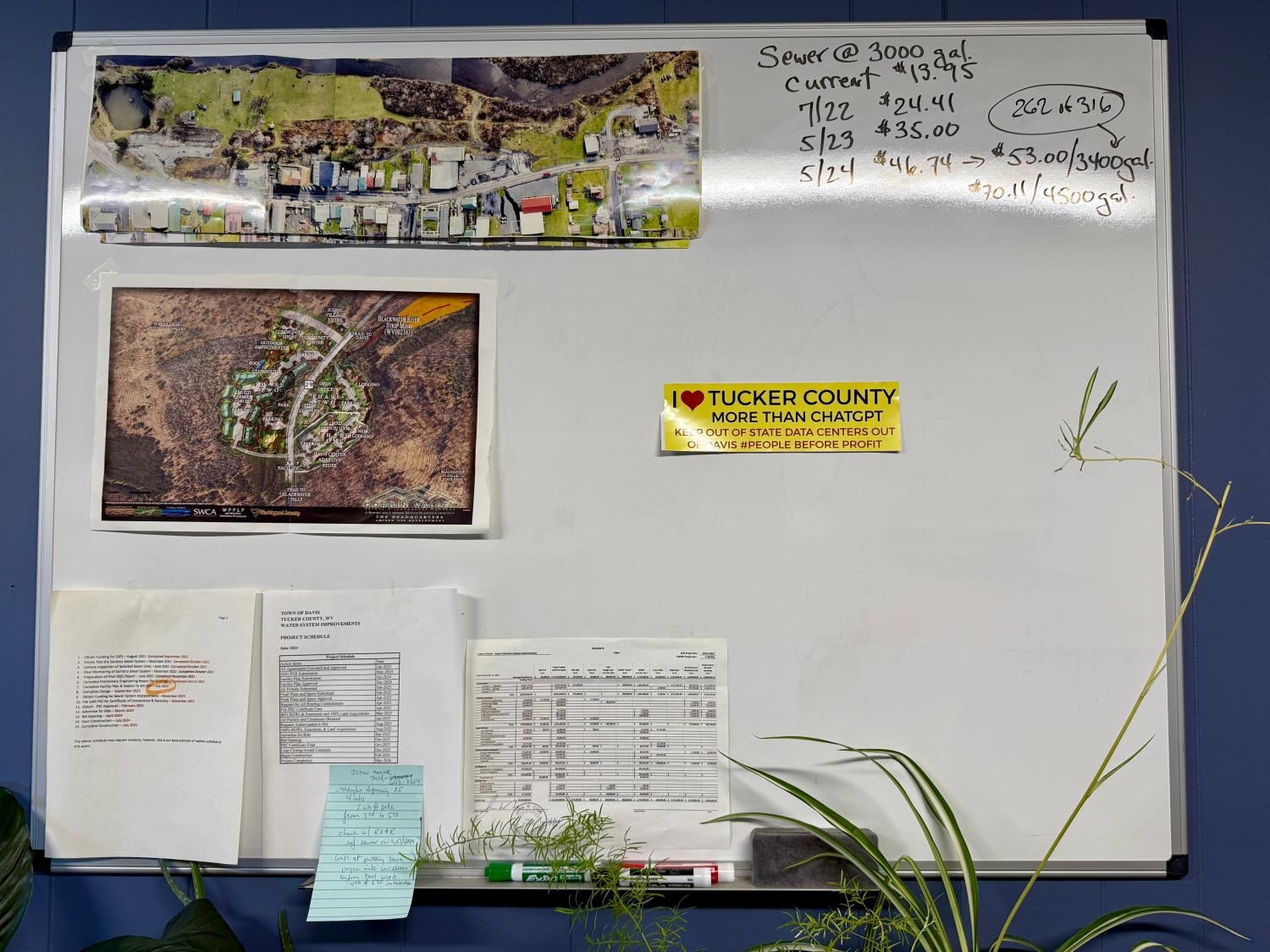

TOMSON: The other thing that we learned was that it would also store 30 million gallons of diesel fuel as a backup source. So we were very concerned with toxic emissions. And the proposed location, which is less than a mile from houses in Davis, and less than a mile from an elementary, middle school in the City of Thomas, that gave people big concern.

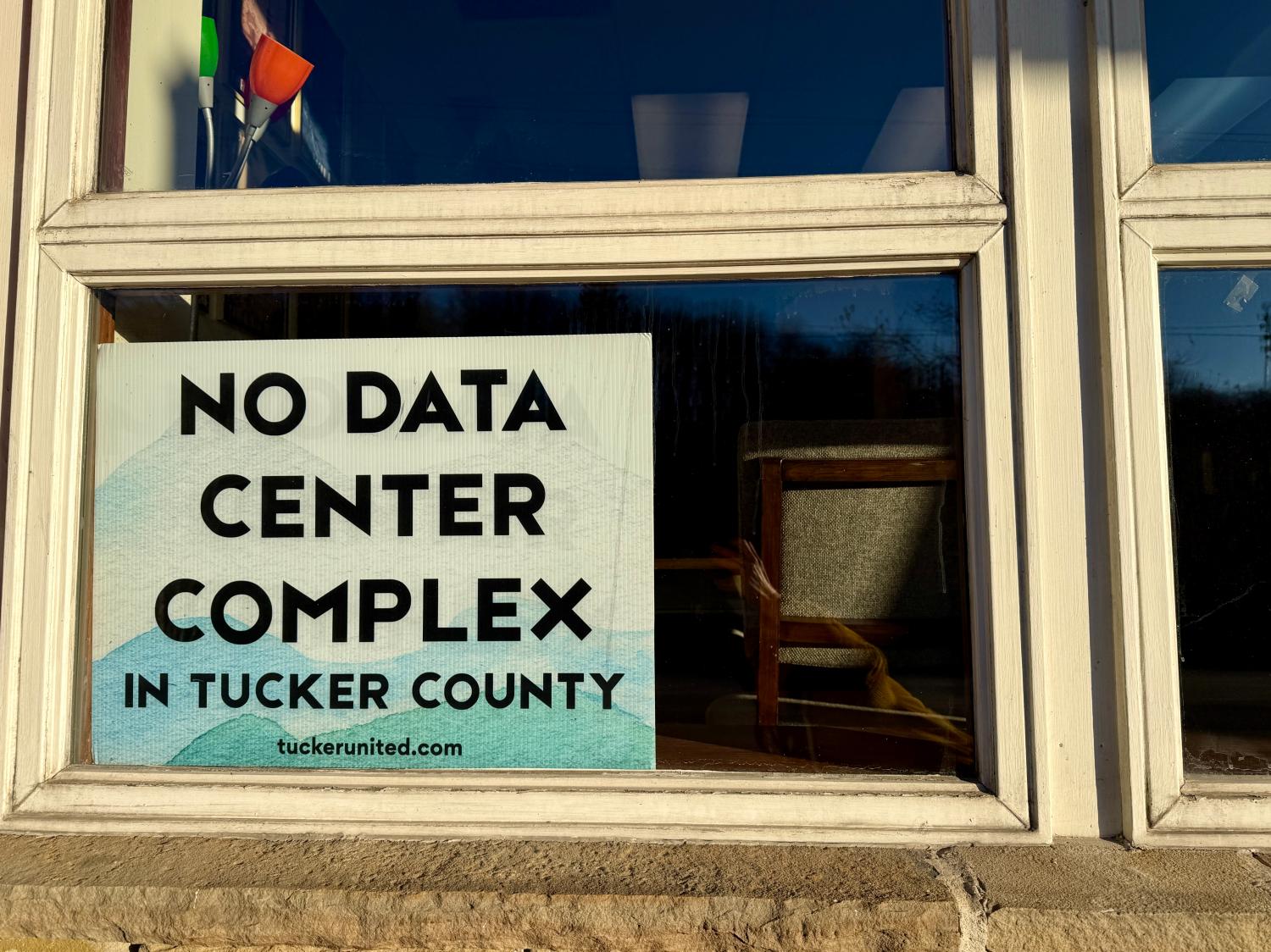

PIPA: That concern was apparent before Mayor Tomson and I even sat down. Across Davis and Thomas, I saw many “No Data Center in Tucker County” signs in windows, storefronts, and on cars.

[19:55]

TOMSON: So between the size of the power plants and the land that they’re talking about having available, it could be 50, it could be a hundred data centers. Which then gave me greater concern about water consumption because data centers are huge users and consumers of water.

And we’ve suffered a drought for the last two summers. We’ve had to go to our secondary water source, which is the Blackwater River. But if the data centers start drawing water out of the aquifer,

[music]

I’m concerned that it’s gonna affect the source water for the creek that we’re using right now and the Blackwater River, which are all co-located in this area. And that gives me, like I said, great concern.

PIPA: Fundamental Data, based in Purcellville, Virginia, is the company that submitted the application for an air quality permit to build the power plant.

Nikki Forrester has talked to Casey Chapman, a Fundamental Data representative, about Tucker United’s concerns and invited him to come down and speak to the group, but Chapman has been cautious about speaking publicly about the project and hasn’t taken her up on the offer yet.

Given the fierce competition in the market, and the large amounts of investment at play, data center proposals are often marked by reticence from developers to reveal lots of detail in the planning stage. This is the rationale Fundamental Data gave for keeping the redactions in the public posting of its application.

In a filing with the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, the company also acknowledged the significant public interest in the project and “committed to engaging constructively with local stakeholders.”

Similar to how many national policymakers and industry leaders talk about data centers, it also characterized the project as a “strategic investment in national and economic security.”

In a statement to The Wall Street Journal earlier this year, the company said the project could span 10,000 acres across parts of Tucker and a neighboring county and will, quote, “be among the largest data center campuses in the world.”

Casey Chapman declined to discuss the project on the record for this episode.

[22:11]

TOMSON: I think they have come to visit the area a couple of times with regards to the power plant. But it’s been under the radar. Nobody knew that they were here at the time. I have spoken with Casey Chapman. He has a West Virginia lineage in his family. He said he came to use the Canaan Valley area for recreation, hunting, and fishing as he was growing up. So he’s well aware of the area.

But they didn’t have any conversation when this this power plant idea was being conceived, and they didn’t take into consideration any of the local concerns. And they discount those. They say that the reaction to air quality and toxic emissions is an overreaction, and that the water won’t be impacted because their plan is to draw water for the data centers from the abandoned mines, which are filled with acid water.

And my concern is that if you drain the abandoned mines of of water, they’re just gonna fill up again with water that’s coming from the aquifer. So regardless of whether you’re directly tapping wells into the aquifer or you’re taking water from the abandoned mines, you’re gonna affect the water supply of the area.

[23:30]

PIPA: There’s no public information on Fundamental Data’s track record in developing a power plant of this size, raising questions about whether it would do the development itself or sell the rights to permits that it secures. That uncertainty is just another thing that gives local residents pause.

It’s important to recognize that not everyone is against the project as it’s proposed, and others would consider it if it were relocated to a different site. While the president of the county commission, Mike Rosenau, did not respond to our offer to discuss the project, he and the other county commissioners have publicly pointed to the growth in the tax base that would accompany the project, providing much needed revenue for a budget that’s become very tight to pay for emergency services, the courthouse, the animal shelter, and more. Balancing the trade-offs of such a large-scale industrial project is a continual challenge in rural development.

[music]

But what adds even more complexity to this particular situation is that none of the local officials here — Mayor Tomson, Mike Rosenau, or any of the county commissioners or elected municipal officials — have any authority in this particular decision.

It turns out the application for the air quality permit was filed the exact same day that legislation was proposed to give the state the authority to approve data centers and micro-grid projects, pre-empting the ability of local governments to enact or enforce any zoning or other types of local regulations — basically stripping local communities of the ability to shape any decisions about these kinds of developments.

The original legislation also had 100% of the property tax revenue associated with these projects going directly to the state.

[25:20]

PARKS: And the legislation was rewritten to direct 30% of the municipal revenue back to local governments, but most of the rest would go to state coffers. And Governor Morrissey has talked about using that revenue to help eliminate the state income tax.

PIPA: The bill, HB 2014, became law on April 30th, 2025. For Kimberly Joy Trathan, who just left her position as a local elected official, it’s hard to fathom.

TRATHAN: There is no option for the municipality or the county to put any type of regulation on anything. To take away that part and undermine that process is really disturbing, to just come in and say, we’re making it easier to greenlight these companies to come in for the sake of bringing possible jobs and money, and you get no say in it, it feels really shameful.

PIPA: As a former mayor himself, Walt Ranalli feels as if there are other options — if locals were given the chance to offer them.

[26:23]

RANALLI: The state took any kind of regulation away from local people, and now is all decided by people who are in Charleston, who everyone knows they might be good old boys when they left here, but by the time they get to Charleston, they have this little clique who makes all the decisions and the heck with the people in that community.

This is out in the middle of one of West Virginia’s most beautiful spots. It’s just not compatible. It’s not good planning. You can have ‘em both if you plan correctly. You know, move it farther out, move it somewhere else. They’re to say that that’s where the natural gas line is. Well they’re putting pipelines all across the damn country for power grids, pipelines. I mean, you can’t pipe it eight miles away and build your power station there?

PIPA: As mentioned previously, the legislation promoted by West Virginia’s governor Patrick Morrissey, was changed to give the local county 30% of the property tax revenue. But the tax is assessed at “salvage rates” that are heavily discounted. And school systems — including Tucker County’s — still get none of the property tax revenue. At least how the law stands now.

Randy Smith, the president of the West Virginia Senate, represents the district that includes Tucker County. Earlier this year, he defended his vote and characterized the fight over its location as one between outsiders and locals. He also suggested the application for an air quality permit was submitted “long before” the microgrid bill was introduced. But in early November, he held a local public hearing and surprised many in the audience by suggesting that aspects of the law needed changing.

PIPA: Senator Smith didn’t respond to our offer to discuss the legislation, but here is some audio from that meeting.

[28:09]

SEN. SMITH: “I’ll be honest with you, I had a hard time voting for it. Uh, I voted for ____, you know, because I’m Senate president if I wanted to kill it, I could have. But it’s kind of hard on your political career to kill the governor’s bill. Uh, so, you know, I met with him and the speaker the same way we met, and he gave us an assurance, anything that if we passed the bill, anything that we need to go back and visit and fix that he would do it, which we can do it anyway, whether he wants to or not we can fix.”

PIPA: Senator Smith said he didn’t catch the funding detail when he voted for the bill — that most of the new property tax revenue will be funneled to the state’s general treasury.

SEN. SMITH: “So that’s something that, that’s something that’s going be addressed this session.”

PIPA: He also recognized that local control is a big issue, and it’s one thing that members of the legislature want to address. What would that mean for the project? Hard to say. It could create some complicated legal issues if the legislation is rewritten.

The state Department of Environmental Protection has approved an air quality permit for the power plant. Tucker United filed two appeals and is now focusing most of their efforts now to get the agency to compel Fundamental Data to reveal more details about the air permit and classify the facility as a major source of emissions.

[29:36]

FORRESTER: The first was about the company’s decision to withhold a lot of information in their air permit. It’s so heavily redacted. We can’t see anything. We know the total amounts of emissions produced, but we have no idea how they calculated them.

PIPA: As I mentioned earlier, Fundamental Data has said those redactions include confidential details about the project.

FORRESTER: The second is over the decision to provide the air permit itself to this company. And so we had one hearing about that so far in which the Air Quality Board of West Virginia basically heard two motions. The first was to allow our lawyer and our legal expert to look at some of that redacted information to verify the emissions calculations.

And the second part, the company wanted to throw out three different aspects of our appeal. So we had basically contended on 17 different issues. They’ve wanted to fight three. The Air Quality Board dismissed two of them. So we still have kind of 15 things that are in play that we are fighting back on.

PIPA: Now, at this point you might be asking, what about the owner of the land where the power plant might be built? Well, that adds yet another dimension to all this. It’s a company called Western Pocahantas Properties, an affiliate of an energy company based in Texas. It’s the biggest private landowner in the county, a situation that’s typical of West Virginia and much of Appalachia: absentee land ownership that is a legacy of its extractive industries.

[31:10]

TOMSON: Normally I talk to them quite a bit on other issues, but not on this one.

PIPA: Several years ago Western Pocahontas developed plans to address a major concern we heard from folks time and again: a lack of affordable housing. The state has recommended that the company be approved for two grants from the federal Abandoned Mine Land Economic Revitalization Program. In addition to housing it would also support a community center with recreation facilities in Davis and other amenities, such as an urgent care center. And the company also recently sold land to The Nature Conservancy.

PIPA: Here again is Davis Mayor Al Tomson.

TOMSON: They’re very good stewards of their land with regards to some of the projects that they envision starting on. They are looking at building workforce housing and low income housing in the area of Davis and Thomas, which is something that we sorely need.

PIPA: And the bottom line is that there are no existing local ordinances or land-use regulations that would prevent the project from being put in the proposed location.

[music]

As County Commission President Mike Rosenau recently said, this is a transaction between a private landowner and a private developer in which local elected officials now have little say.

PIPA: As Nikki mentioned earlier, Tucker United has evolved from just being against the data center. Its members have committed themselves to thinking about economic development for the county, realizing that the controversy has surfaced hidden issues that need to be dealt with. I had lunch at the Purple Fiddle with a few of the group’s members while I was in town.

[32:58]

PIPA: And it’s easy to say. It’s easy for, for people to look and say, oh, you’re against everything. What else would you want to say to people who might, you know, have a kneejerk reaction to what y’all are doing?

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 1: There are issues with housing and other kinds of stuff, but our tourism economy is one of the primary drivers of economic development. And it’s homegrown development. We have small business owners who are, you know, building their families and growing their lives here. But it’s, it’s, it’s been so long and such a hard fight, and then all of a sudden it feels like this is gonna kick the legs out from the stool from everything that’s already here.

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 2: I mean, I think we’ve talked a lot about that, um, just internally. I mean, I think, you know, I, I, I don’t think I’ve ever been so engaged in, like, a coalition from the inside and … yeah, like, we very quickly realized like we’re not, like, our goal is not to, like, shoot down a project that we think is sketchy. The goal is we we want positive economic development here that’s sustainable.

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 1: Yeah. And I think we’re learning from other long term community movements that start around one issue that galvanizes people, but that it uncovers long-term issues that show that working together is the way of the future.

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 3: But, um, it is, it’s a challenge. It can be a challenge for people to live up here. And one of the things that I think we’ve already done as an organization, segueing off to help the community, is we have already done that. We’ve done fundraisers for the local animal shelter. We’ve done fundraisers for the local food pantry, and these things just kind of, they happen because there was a need.

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 2: You know, you can have other sides saying, oh, you’re anti this, you’re anti that. And it’s not that at all. We’re, we’re pro-Tucker County and we want to find a way that we can all work together, but, like, leverage this thing that we’ve built to be like, okay, look, yes, we have people, some people who have very little and some people who have a lot.

LUNCH PARTICIPANT 1: If the data center goes away, I don’t think Tucker United is going away.

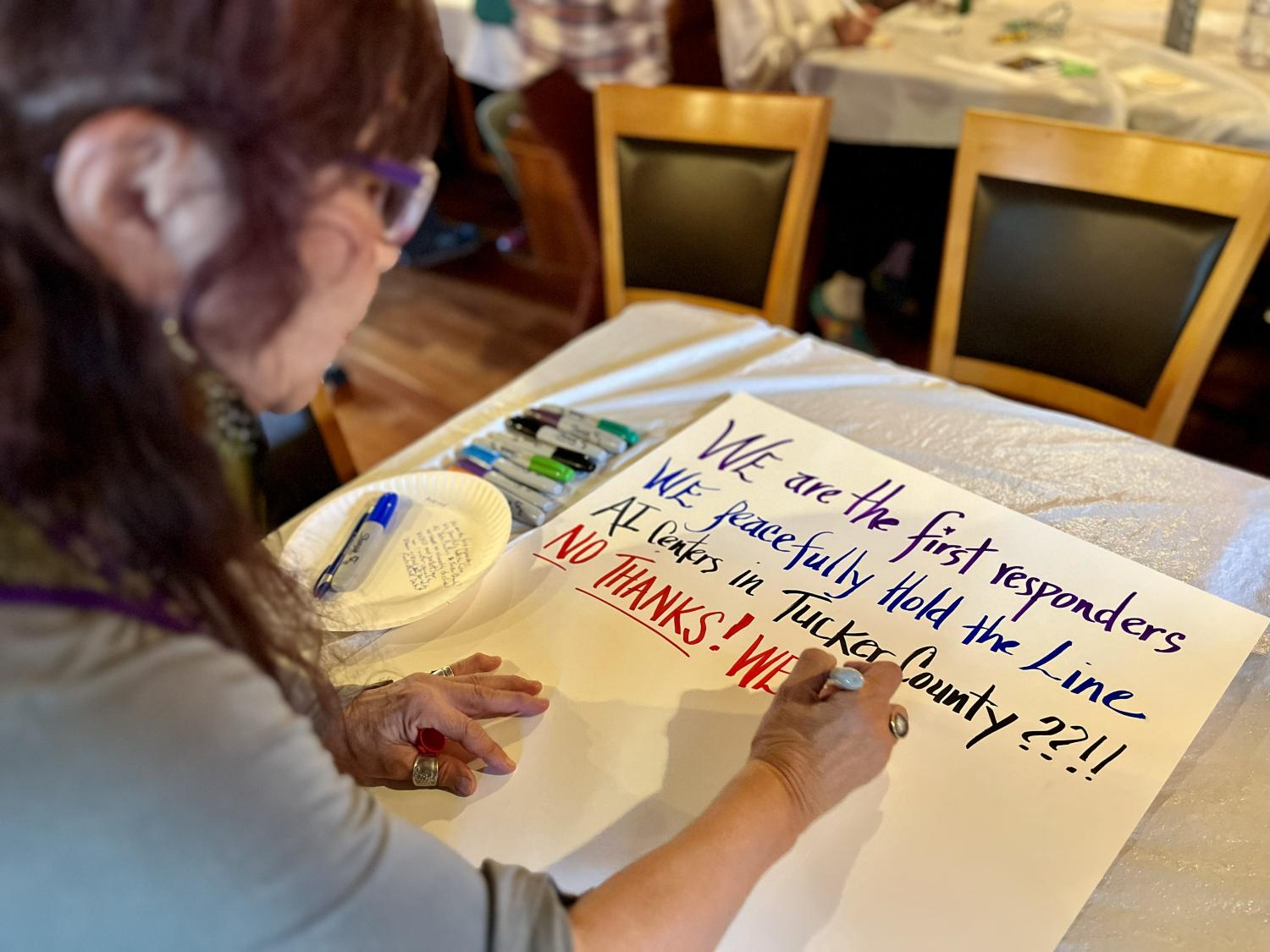

PIPA: West Virginia’s legislative session starts in January. Tucker United has been busy. In late November, the group met to make posters for their upcoming protest in Charleston.

[35:06]

SPEAKER 1: Today we’re making posters and we’re making Christmas ornaments, but the posters are for the West Virginia DEP Air Quality Board hearing that will be taking place in Charleston. And it’s, uh, important for us to have a presence to remind the DEP of their role to be protecting communities and protecting the environment. By issuing the permit, they failed in their duties. And so this hearing is fundamentally about trying to get them to do their duty. And to, if possible, rescind the permit or at least move it to, uh, a more restrictive permit.

Um, so that is why we’re making signs to remind the public that we are not gonna sit quiet while our mountains and our air and our health are in peril.

[sounds of protest in Charleston, December 3]

PIPA: Many of the people here in Tucker County are passionate about their place. Yet the fact is the technology sector is driving much of America’s economy right now. The one thing that has bipartisan support in Washington, D.C., is that we need to win the technology race globally.

[music]

There is lots of encouragement coming from the White House and other national policymakers to move quickly, and many states are eager to attract these centers.

[36:40]

HANNAH: I’m an incurable optimist.

PIPA: Heather Hannah again.

HANNAH: I have, I have a lot of hope. My life in West Virginia not only informs the flavor of what I do in terms of the music that I write, but it’s in every note. It’s in the words that I choose and why I choose them. I can only write true story songs.

PIPA: Heather sees a responsibility for artists to reflect the change coming through their community and to raise the important questions.

HANNAH: Faith is increased when there’s a witness. Then we start to question, well, why can’t it be like this always? Why can’t we always have this feeling? Why can’t we always hear birds? Why can’t we always see stars? Why do I have to give up the stars? Why do I have to let go of the sound of this river? Why can’t it? Why must that be some farfetched toast at Christmas? You start to question the ideas that have kept you entangled and separated from your joy and separated from your peace, separated from your humanity.

[music]

So we’re just gonna be here. We’re gonna be here doing this, being this, embodying this. And whatever comes, we’ll meet it with resolve and compassion and creativity and courage. Because we’re not going anywhere. This is home. This is home. We’ll find a way. We always have.

PIPA: This current situation in Thomas and Davis gets to the heart of so many dimensions of what it means to live rural, where local resources can get inextricably tied to the country’s economic growth and security; where the balance of economic development that’s supports and sustains local livelihoods can be tough to strike; and where local control can sometimes feel as if it’s being overwhelmed. Yet, also, where resilience and authenticity remain strong. Remain … home.

Thanks for listening.

[music]

To provide further policy insights based on this episode, we also publish a Q&A with an outside expert on the Brookings website. You can find the link in the show notes.

Many thanks to the team who makes this podcast possible, including Fred Dews, supervising producer; Molly Born, producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video manager; Zoe Swarzenski, senior project manager at the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings; Adam Aley and Elyse Painter, also in the Center for Sustainable Development, who provide research support and fact checking; and Junjie Ren, senior communications manager in the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings.

Also, my sincere thanks to our great promotions team in the Brookings Office of Communications and Global Economy and Development. Katie Merris designed the beautiful logo.

Finally, support for this podcast is provided by Ascendium Education Group. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication or podcast are solely those of its authors and speakers, and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or its funders. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

You can find episodes of Reimagine Rural wherever you like to get podcasts and learn more about the show on our website at Brookings dot edu slash Reimagine Rural. You will also find my work on rural policy on the Brookings website.

If you like the show, please consider giving it a five-star rating on the platform where you listen.

I’m Tony Pipa and this is Reimagine Rural.

More information:

- Listen to Reimagine Rural on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Find out more about the Brookings-AEI Commission on U.S. Rural Prosperity.

- Discover more research on Reimagining Rural Policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastWill a data center be good for Thomas and Davis in Tucker County, West Virginia?

Listen on

Reimagine Rural

December 10, 2025