Last week, we wrote that we thought President-elect Donald Trump would be hard-pressed to deliver on his promises to “bring back” large numbers of America’s lost manufacturing jobs, even if he does renegotiate the nation’s trade deals. The reason: Manufacturing work is increasingly carried out by robots, rather than people.

The problem for Trump and blue-collar workers is that when manufacturing returns to the states (and several trends favor that), the associated job-creation will not be what it once was. Nor will the difference be just a minor effect – it’s going to be major.

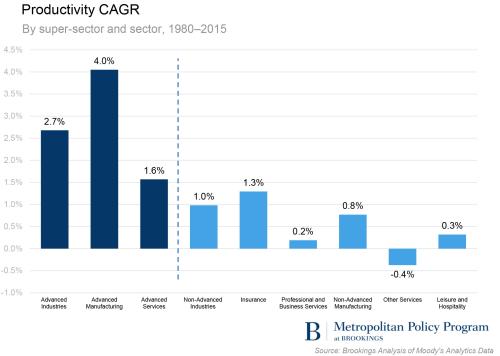

Which is why we want to add this telling chart to the discussion about the future of manufacturing jobs. Take a look at this single, stark graph depicting the 35-year-history of U.S. manufacturing efficiency:

Here you can see in the two line plots that the inflation-adjusted output of the manufacturing sector is as high as it has ever been, while employment declined by more than 6 million jobs over 35 years. Viewed positively, the diverging output and employment lines represent a success: They reflect solid increases in U.S. manufacturing productivity. But now look at the declining series of gray bars. These bars report the steadily declining number of workers required to generate each $1 million of manufacturing output during the time period, given the sharply increased productivity of the sector.

And the story is dramatic: In 1980, it took 25 jobs to generate $1 million in manufacturing output in the U.S. Today, it takes just 6.5 jobs to generate that amount—and that’s after five more stable years of little change.

The Trump administration will need to “bring back” a huge amount of manufacturing activity in the next few years if it is going to meaningfully address the plight of displaced production workers with new manufacturing jobs. How much of a manufacturing renaissance would be needed to repair the breach? Since 1980, the nation has lost some 6.4 million manufacturing jobs—more than one-third of the sector’s employment base. Restoring just half of those jobs in the next four years would require, factoring in current manufacturing efficiency and job sparseness, a massive 26 percent surge in manufacturing output. To put that in perspective, this additional needed output would be equivalent to about 100 Tesla “gigfactories.” (And in fact, Tesla only plans to hire 6,500 people to produce an anticipated $100 billion in output over two decades, meaning its highly-automated operation will require just 1.3 jobs to generate $1 million output annually!).

Note also, for a further comparison, that President Obama only managed to generate half a million manufacturing jobs in his first term—a performance that benefited from an $80 billion auto-industry bailout and post-recession global trade boom.

In short, President-elect Trump’s promise to address the plight of displaced manufacturing workers through reshoring is not as straightforward an answer as it seems. By all means, the nation should demand fair trade and aggressively employ the anti-dumping provisions in existing trade pacts to rebalance the playing field. By all means, the nation should address the disrupted careers, depressed wages, and sense of marginalization of the nation’s dislocated production workers. And by all means the nation should bolster its critical manufacturing sector. But to hang frustrated workers’ hopes of relief on large-scale hiring in an increasingly automated, hyper-efficient manufacturing sector appears to be severely misdirected. It would be far better to focus on preparing workers for the rise of the robots than to promise them jobs that will be done by machines.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why Trump’s factory job promises won’t pan out—in one chart

November 21, 2016