Click here to view the technical report, added on Friday, October 31, 2025.

The well-being of Black boys and men is vital to the economic and health outcomes of Black families and the communities where they live, therefore it’s important across communities in the United States. When Black boys have the opportunity to experience a normal childhood, with supportive family connections and communities, and positive engagement with the economy, they become Black men who can mentor younger generations, build important social networks, and provide both emotional and financial support to their families and communities.

Yet, narratives dating back hundreds of years seek to undermine this perfectly normal set of expectations for Black boys and men. Throughout American history, Black boys and men have been uniquely characterized using derogatory and degrading language. Black boys and men are negatively portrayed as brutes, thugs, drug dealers, criminals, absentee fathers, and uneducated, to name a few portrayals and narratives seen in media, popular culture, politics, and social commentary. When positive examples do appear, the success of Black boys and men is often framed as miraculous, portraying them as exceptional individuals who overcame the traps of poverty, transcended the challenges of growing up in a single-parent household, or built an exceptional character, stellar aptitude, and tenacious grit.

The frequent repetition of Black boys and men as societal failures seeps into policy preferences, proposals, and discourse, and such negative narratives permeate the design and implementation of programs, services, and policies.

These narratives influence access to resources that can spur social and economic mobility and health resources that can improve quality of life. In response, the Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative team undertook a two-year partnership with multiple local communities to redefine this narrative and to have Black boys and men define what it means to experience well-being. Research has shown that positive narratives of Black boys and men enhance strategies to navigate discriminatory experiences and promote resilience. Many interventions that include mentoring, supportive networks, and addressing social needs will improve well-being and health outcomes. Our goal was to have Black boys and men lead the definition of well-being and determine how public policies and other approaches can be leveraged to promote wellness in Black life.

The Brookings Institution partnered with four community organizations for a multi-year project to explore the question: What is well-being for Black boys and men?

The most important strategy of this project was to work directly with communities as we explored definitions of well-being for Black boys and men. To do this, the Brookings team worked with community organizations to convene multiple community conversations in three locations: Little Rock, Arkansas; Baltimore, Maryland; and Montgomery County, Maryland. As a result, an initial part of the engagement process was establishing partnerships with four local organizations to enhance outreach, recruitment, and facilitation efforts. The organizational partners included:

- The Urban League of the State of Arkansas and Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arkansas (BBBSCA), who served as local partners in Little Rock, Arkansas

- Montgomery County Collaboration Council (MCCC), in Montgomery County, Maryland.

- Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP), in conjunction with the Haywood Burns Institute, in Baltimore, Maryland

Working with community partners, the WIBL project adopted three goals:

- Elevate the experiences of communities of color that contribute to the vibrancy of their communities, state, regions, and the country

- Ensure that communities of focus have shared ownership of the project across all phases and continue efforts to support the well-being of Black boys and men after the project ends

- Inform public policy discussions and decision-making processes at the local, state, and national levels about how to invest in the well-being of Black boys and men in communities across the U.S.

The multiple conversations across these three locations were facilitated by our community partners. For more information on our methodology, please see the technical report.

Community at the Urban League of the State of Arkansas. Credit: Joseph Crew

Community at Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arkansas. Credit: Corrigan Revels

Community at Montgomery County Collaboration Council for Children, Youth, and Families. Credit: Naaman Brown

Community at Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs in Baltimore, MD. Credit: Naaman Brown

When we asked our community partners about a lesson learned or insights they learned from how they engaged with their respective communities on this project, one partner attributed their success to: “Years of relationship and never over asking, show and prove.” Following the “show and prove” approach, we want to “show” how Black men conceive of the concepts of well-being and illustrate examples of how to enhance well-being through programs and policies. We use the term “dimensions” of well-being as a way to organize the major themes discussed below.

Throughout this report, we examine both the role of narrative change and the structural challenges shaping the well-being of Black boys and men. The findings below highlight how participants describe the lives they aspire to, the circumstances they seek to remedy or change, and the futures they hope to create for Black boys. Addressing structural barriers begins with communities taking stock of current realities and envisioning how different conditions can influence life trajectories while fostering more positive opportunities for younger generations.

Well-being as thriving and health promoting

Participants noted that the WIBL project provided an open space for Black men to build community and share their authentic selves in ways that supported their well-being. These spaces offered opportunities to articulate what thriving and growth mean to them and to envision the futures they want to create.

… feeling a sense of belonging and [that] I'm supposed to be here, like this is where I'm supposed to be right now. And I feel really well about being here tonight. And this is going to improve my wellness and my well-being.

Montgomery County, Maryland

I think making sure we have human connection. As Black men, my diagnosis, self-included, I think we are some of the loneliest, most isolated people in the world, even in this space. I think we're already ahead of a lot of people, but you can have a conversation for years and it'll take you years to get to anything of substance. And so, I feel like if you're in a cave alone, then they physically get sick because we need human connection. And so, I think wellness, for me, is human connection, and for Black men it's particularly important.

Montgonery County, Maryland

Individual well-being

Well-being was defined at the individual level by how participants understood their authentic identity, sense of place, and purpose in life. Their reflections shaped a narrative that recognized life would not always be perfect or easy. Yet, with skills, access to resources, support from others, faith, good health, and perseverance, they believed it was possible to meet basic needs and achieve success.

I believe defining well-being is just being [in] a place in life where you can live in your truth and not have to be really worried or concerned about just being you.

Little Rock, Arkansas

… purpose, being purpose-driven. There was a point in time in my life where I was waking up with no purpose, and comparing it to the time I'm living, waking up with a purpose, is completely different.

Montgomery County, Maryland

And so, happiness is definitely a goal in life. We all want to have happiness, and that's a part of well-being, or maybe a result of it.

Baltimore, Maryland

Family well-being

Across the conversations, many participants emphasized family as central to their identity, a foundation of support, and a core network sustaining Black boys and men. Adult participants noted that as they begin to build families of their own, they want to ensure their loved ones also experience well-being. Some also reflected on difficult family dynamics in childhood or adulthood, noting how those experiences shape their sense of wellness and inform the decisions they make to counter such challenges.

They saw other family members, the same uncles that raised me now raised them, so they have a support team. I intentionally put them around [my kids] to see what I saw [and] get what I got, so they can see what made me. And then also developed them to be better than me. Yes, this was my whole goal.

Little Rock, Arkansas

I think one part of what well-being is having a good support system in addition to everything else everyone's just saying.

Montgomery County, Maryland

This is a picture of mom and dad, and they were my foundation. And what my dad went through then...they called them Negroes back then in World War II. The struggles that they had, I draw strength from them every day.

Baltimore, Maryland

Community

The meaning and impact of well-being for Black boys and men are deeply shaped by their immediate communities. In many cases, community itself becomes an extension of family—encompassing the people and organizations that provide resources, safety, support, and the freedom to be vulnerable.

I feel like what defines that well-being is collectively getting together ... to reach back, like it was said before, and bring up our young Black men into a world that they can profit, they can benefit, and they can strive and survive in.

Little Rock, Arkansas

So, well-being, it's like knowing that there's people who want well for you too, and being around those people, regardless of what, where, what you're doing, where you're coming from, how much you got.

Little Rock, Arkansas

So, wellness, to me, is community. It really is. I keep seeking out people and just seeking out that communal living, because every time I have that, I feel safe, I feel well. I don't know how to describe it any better ... I know when I'm not well because I'm not around people who can encourage me. When I'm well, I'm with community.

Montgomery County, Maryland

Resources

Participants emphasized the need for resources—and the redistribution of resources—as part of an ongoing strategy to enhance the well-being of Black boys and men. They acknowledged that while many resources already exist within their communities to strengthen social and health outcomes, these often require tailoring to meet current needs and interests. Participants also highlighted the potential to leverage resources to create new programs and services that support education, workforce development, and family dynamics across the life course. In these conversations, resources were frequently described as tools to help “fix” broken structures and systems.

We don't have a short list of challenges, and you can't fix everything with the same tool. So, some actual people need not just financial resources, but actually things to address problems that have gone on for generations and just have never been addressed so they [are] being passed down in a real way.

Little Rock, Arkansas

We also got to dabble into what seemed like the well-being part of that, which is like building a foundation within your house, making sure that the things are being done appropriately in your house, whether you are financially stable, to do great things, or just financially stable to survive, but to make sure that your household is right.

Little Rock, Arkansas

It's a stressful thing, but it's a well-being feeling of knowing that right now I don't really got to check my account. I remember not knowing if I got that in the account.

Montgomery County, Maryland

Safe and supportive spaces and people

Community partners and participants helped ensure this project created a safe space for conversation, emotional expression, healing, therapeutic moments, disagreement, and community building. Participants noted that these kinds of spaces are ones they would like to access more regularly, even beyond the life of the project.

I feel like a big part of that was my foundation, and it started at the house. I just had a solid foundation starting from home. So now it's wherever I do go, no matter the company, or if its faith, at church, at my internship, or just on campus, I'm just able to be safe and free and vulnerable to myself that even if my external conditions don't allow for that, I'm good, because I'm me.

Little Rock, Arkansas

Boys and Girls Club [and other] after school activities, they provide a different environment. Like one of the gentlemen were saying back here, about football practice. They provide a different environment than the neighborhood that most Black boys and men are growing up in.

Baltimore, Maryland

… going to college and then joining a fraternity. But those are two very elite, elitist type [of] experiences. And only 6% of the world is college educated, so you see what I'm saying. So, like how realistic is that? Why does he have to wait until he gets to college to find community amongst other Black men?

Baltimore, Maryland

The church is a gathering space, a way for us to get all on the same page, for us to get the energy we need to get through the week.

Montgomery County, Maryland

I think fraternities serve a really, really effective role in our respective communities. Brotherhood, fellowshipping, service to the communities, giving back, fundraising, every last one of the Divine Nine northern non-Greek organizations.

Montgomery County, Maryland

I would say, HBCUs.

Montgomery County, Maryland

Creating a narrative change

The views, perspectives, and stereotypes shaping the identities of Black boys and men have often been harmful. Participants sought to offer alternative narratives that portray Black boys and men as complex, emotional, and responsible, rather than reducing them to one-dimensional caricatures. They also noted that certain social circumstances, such as incarceration, have influenced perceptions of Black manhood and are often treated as mundane, normal, or even “cool.” Participants described these narratives as detrimental to the long-term health and well-being of Black boys and men and emphasized the need to challenge and minimize them.

Whatever state you're in, Black man, that's who you are. So, we always get caught up in the community, trying to compartmentalize what we should be and what we should look like, how we should think. I'm sorry. There is no true mode for what a Black man is other than a Black man. That's it. Each one has a different mode. We have a whole lot of similarities. We have a lot of stuff in common, a lot. We have the same struggles. But, to just try to put us in a box with the hashtag of Black boy joy, because then what happens when you have the white man joy, the white woman joy, then it diminishes what that is. But you can never diminish what a Black man did just by him being exactly who he is.

Little Rock, Arkansas

Our success stories, our storytelling is [missing]. We got to do better job in telling our story … There's value in the story. There's value in people who look like you hearing a story about a person that is very similar to them, whether it be their background or their everyday life.

Little Rock, Arkansas

So, one of the stereotypes I was thinking about was how, from the outside, we take initiative to be 'too cool to do something.' This is a stereotype that leads us to not take care of ourselves.

Montgomery County, Maryland

And I found that through my voice, Black boys [and] Black men need to know how to talk. You can't fight your way out of it; you need to talk. And that's your saving grace. You make an ally.

Montgomery County, Maryland

Some of the things that you … might want to think about … is how does he feel about his life? How is he feeling in it? Not just what these are sort of on paper, what he looks like, what is his life satisfaction? What is it? And then you can eventually get to these ... What are these aspirations?... So, I think what I'm hearing from some of the conversation is , right now, this person does exist in Baltimore, but there's limited access to this for a lot of people. So, we'll eventually get to the point in this world where all these are the typical headlines about Black men, right?

Baltimore, Maryland

Mental and emotional well-being

Health was one of the most common ways participants discussed well-being. Their reflections suggested that well-being should be approached holistically, integrating multiple identities and dimensions of health. Participants noted that Black boys and men often deny themselves opportunities to explore their whole selves and that external influences frequently limit their understanding of what well-being can be.

I definitely think that's something we need to change. We don't need to change that our children are emotional. We need to change that people are looking at our men in this way. What is the problem with our men being emotional? We have the right to be that, and I think our men should have the right to be that as well. At the end of the day, they need just as much support as we do, especially this day and age, especially given that our Black men go through things that other men don't. They should be able to come to us as their mothers, fathers, sisters, cousins, everything, and be able to express it the same way we did. So no, I get that. I understand that. I'm just saying we should change that, like as a community, we should be trying to change that.

Baltimore, Maryland

Many of the solutions generated across community sites focused on improving the physical and mental health of Black boys and men. Participants recognized that when Black boys and men are healthy, they are better able to thrive. When facing health challenges, they emphasized the importance of seeking help, relying on friends and family networks for support, and having accessible resources. Conversations also highlighted recommendations for programs, services, trainings, and policies that support well-being across the life course and reflect the diverse roles and identities of Black boys and men. Examples included support for residential and non-residential fathers, as well as mentorship or apprenticeship programs offering vocational training. Other strategies included:

- Create and support safe spaces for Black boys and men to talk, network, share experiences, and exchange resources, with particular attention to those who are most vulnerable.

- Enhance financial literacy through programs, workshops, and other opportunities that prepare Black boys and men for financial stability.

- Strengthen workforce development to support not only job preparation but also long-term career building. Sustained engagement and preparation can promote social mobility, increase representation across economic sectors, and enhance communities’ readiness for shifts in career-based industries.

- Expand education, training, and apprenticeship programs that facilitate career entry and transitions, especially in response to shifts from manufacturing to technology-based industries. For example, shifts from manufacturing to more technology-based industries can be an area of focus for some development programs.

- Provide life-stage and life-course mentoring to help Black boys and men navigate unique experiences, opportunities, and challenges across their journeys, while supporting their families and communities.

- Build the capacity of youth-serving programs and services to address racial, gender, and sexual identities.

- Identify and prepare community members who are passionate about working with Black boys and men so they can recognize emerging needs and connect participants to resources, services, and programs.

- Increase diverse representation in schools (e.g., teachers, principals) and among policymakers and other community leaders.

The reflections discussed above help illuminate well-being for Black boys and men across the many dimensions that matter to them. First, participants emphasized the importance of conditions that support family and community well-being, including access to resources, safe spaces, and opportunities for fellowship. Second, they highlighted individual well-being, focusing on robust health and access to resources that support physical, financial, and mental health. Finally, participants observed that Black males face the unique and unjust burden of combatting centuries of racism, which manifests in experiences such as social isolation, mental health stress, and broader well-being outcomes.

Below, we discuss ways to operationalize the recommendations emerging from these community conversations. The central theme centers on increasing resources for Black boys and men to build community in safe, dedicated spaces. Partnerships among Black boys and men, community-based organizations, researchers, and policymakers are key to bringing these recommendations to life.

The goal of the Wellness in Black Life project was to collaborate with community members to generate definitions of what well-being means for Black boys and men and to outline public policy agendas and other strategies that can support their well-being. The results of this collaborative effort highlight multiple opportunities for Black boys and men to inform and lead policies that are meaningful for them and their communities. Building on the insights offered by participants, the Brookings Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative team identifies several key opportunities:

First, municipal, state, and federal leaders interested in supporting the vibrancy of Black communities would benefit from working directly with Black boys and men to define policy priorities, strategies, and implementation processes.

Second, political and policy leaders should view the themes generated in this project as benchmarks for evaluating the effectiveness of their efforts to support Black boys and men. The indicators and survey tool developed through this project can serve as a starting point for such assessments.

Third, there is a significant opportunity to scale engagement with Black boys and men in articulating what it means to experience well-being and the policies that can support it. Using the collaborative recruitment, convening, and feedback methods central to the Wellness in Black Life project can facilitate this engagement. As participants emphasized, bringing Black boys and men together in safe spaces to focus on their well-being and the well-being of their communities is valuable in itself.

Fourth, policymakers who are representative of these communities are more likely to champion policies that support Black boys and men. Collaborations among organizations focused on training public policy leaders can help create a policymaking framework responsive to the needs and aspirations of these communities.

Finally, funders of public policy and community well-being research can have a significant impact by prioritizing community-based research that focuses on the assets of communities of color. Leveraging these assets to generate programmatic and policy enhancements can create sustainable improvements in social, health, and well-being outcomes.

Perhaps the most important lesson of this collaboration is that engaging Black boys and men in ways that intentionally center their experiences and wisdom is itself an act of narrative change—one that produces lasting positive effects on social health and well-being.

-

Technical report

This report outlines the community-engagement process conducted by the Brookings Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative (RPII) in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for the Wellness in Black Life Project (WIBL). WIBL is a community-based project focused on building definitions of well-being for Black boys and men by Black boys and men across three communities: Little Rock, Arkansas; Montgomery County, Maryland; and Baltimore, Maryland. We describe how these cities were selected below. Each partner organization in these sites held a deep commitment to building community connections to enhance and promote well-being.

The RPII team worked directly with local communities to learn how Black men want to define, discuss, and assess well-being for Black boys and men and how it will impact Black communities. This report documents the methods used to convene community members, summarizes our community-engagement process and feedback received, and highlights how this input will shape the initiative moving forward. The social risks many Black men and boys face despite pathways to social and upward mobility have many consequences throughout their life-course. These are well noted in the literature. Engaging Black men and boys by partnering with community-based organizations may not only strengthen social ties but also reimagine opportunity structures and well-being protective factors that can be sustained and replicated in other cities across the United States.

This technical report accompanies our main findings report highlighting key definitions of well-being generated by Black men in our study sites. Important insights from this study suggest:

- Promoting support initiatives to enhance well-being for Black boys and men can come from many different individuals, such as family, friends, religious leaders, teachers, mentors, and coaches. These individuals exist in many different organizations and can deepen and expand support structures and resources.

- Black boys and men need safe spaces for discussions about individual, family, and community well-being.

- Black boys and men want to guide narrative-building and counter existing narratives about them that have led to historical policymaking practices that are part of the root causes of their social inequalities.

- Convening Black men to discuss strategies for community change will require sustained efforts and connections with community-based partners and should include advocacy strategies to promote policy change.

- Institutionalizing community-engagement with Black boys and men requires committed partners, collective access to resources, and influencing policies to increase the quality of life, longevity of life, and well-being.

Project background

Across the vast body of scientific literature, numerous reports, statistical analyses, and philanthropic efforts have drawn attention to the wide range of challenges facing Black boys and men. Yet few of these initiatives have been led by community-based organizations or shaped by the voices of Black boys and men themselves. Too often, global conversations, well-being measures, and policy outcomes overlook communities of color—particularly Black boys and men—creating a troubling information gap for public health research and policymaking. There is more we can do to strengthen emerging programs and policy recommendations that address the unique barriers Black boys and men face, while leveraging the assets within their social networks. Advancing these efforts requires the leadership and guidance of Black boys.

Our work and this report aim to advance the growing body of literature on best practices for engaging Black men in social science research. Across disciplines, studies have consistently shown that communities of color are less likely to participate in research, particularly in projects that use clinical or experimental designs. The cultural, historical, and social factors underlying Black communities’ and Black men’s reluctance to participate are deeply rooted in centuries of unethical practices by researchers, clinicians, universities, hospitals, and museums.

Engagement methods and process

The research project used multiple methods. The Brookings team began with a literature review and found that Black boys and men were largely absent from the interdisciplinary literature on “well-being.” Instead, most studies and programs focused on violence prevention, high school dropout rates, sexually transmitted infection prevention, and prostate cancer. The concept of well-being for Black boys and men remains underexplored and deserves the same level of attention and investment—through an asset-based framework aimed at improving their social and health outcomes.

The initiative was carried out over a three-year period from September 2022 to August 2025. The project unfolded in three overlapping phases.

Phase 1: The initial phase of the project focused on literature reviews, developing research design, securing Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, and selecting the local partner organizations.

Phase 2: This phase centered partnership exploration and formation by identifying community-based organizations that develop and provide programs and services to Black boys and men. We also formed an Advisory Board to collectively establish research priorities. We selected four community research partners in three geographic areas: Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arkansas and the Urban League of the State of Arkansas (Little Rock, Arkansas); Montgomery County Collaboration Council for Children, Youth and Families (Montgomery County, Maryland); and the Haywood Burns Institute and Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (Baltimore, Maryland).

Phase 3: We launched community convenings in each geographic area with the community research partners leading recruitment and convening efforts. During the community convenings held as part of the second phase, we documented discussions around well-being. These convenings took place from October 2024 to March 2025. At the conclusion of the community convenings, we delved into data analysis—facilitating feedback sessions with local communities and drafting and revising research reports to disseminate.

The project timeline was intentionally flexible to accommodate partnership building, occasionally adjusted to meet community needs and times to meet; meeting days and times were selected by community partners in response to local events and emerging opportunities for deeper engagement.

The objectives of the community-engagement process were to gather shared definitions around well-being, with a particular focus on Black boys and men. Black boys and men shared their experiences and expressions about well-being and identified the roles policy and community leaders play in shaping their well-being. The convenings aimed to collaboratively identify and develop strategies and solutions to enhance the state of well-being of Black boys and men, by discussing how policies and programs can be shaped by these strategies and identifying resources needed to support them.

The literature reviews from Phase 1 guided us to consider counties and cities with a mix of social challenges and assets. These assets in one study were framed as opportunities for social mobility as a result of less poverty, higher life expectancy for Black men, and a higher percentage of elderly civilian veterans. The literature review allowed us to learn more about well-being research studies and programs and facilitated our selection of community partners. Lessons learned from this phase guided our search for organizations working directly with Black boys and men to provide care, support, and mentoring. We collected information from nonprofits and other community-based organizations in cities and metropolitan areas such as Little Rock, Arkansas; St. Louis, Missouri; Atlanta, Georgia; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles, California; Detroit, Michigan; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Baltimore, Maryland. This information provided insight into how different organizations approached addressing the needs of Black boys and men and how their organizational structures may be leveraged as partners for this project. After selecting a sample of organizations, we conducted stakeholder interviews to learn more about their work and to introduce the project’s goals. Many organizations noted their limited capacity to facilitate the project’s activities.

The Brookings team partnered with four local organizations who agreed to facilitate community conversations within their geographic area with Black boys and men. To facilitate the recruitment of participants, the Brookings team worked with its community partners to develop promotional and marketing materials to depict well-being in Black communities by using images of Black boys and men. The partner organizations handled the direct participant recruitment process and used similar but personalized outreach strategies to target and recruit participants to ensure a diverse, committed, and representative group of participants for community-driven conversations. Outreach efforts included posting social media messages, mailing direct personalized correspondence, distributing flyers, partnering with local clubs and initiatives, utilizing professional networks, and reaching out to community and civic leaders.

The organizations recruited Black men, 18 and older, who both lived and worked in the area they served. Collaborating organization did not recruit minors, citing several barriers to recruitment and the need for repeated engagement with minors and their parents or legal guardians. Protocols were revised to ensure questions during community conversations prompted participants to reflect on different life stages and consider how the discussion topics might influence Black boys.Others interested in advancing the health, well-being, and social mobility of Black boys and men were also invited to participate. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with IRB guidelines.

Community convenings

All four partner organizations utilized a network-sampling strategy to recruit participants for community-driven conversations. Similarly, three of these programs, Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arkansas (BBBSCA), Montgomery County Collaboration Council for Children, Youth and Families (MCCC) and Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP), took broad approaches to the recruitment process, drafting social media posts, emails, and flyers to draw in attendees. Notably, the Urban League intentionally avoided the use of social media for the recruitment process to create a consistent and private space where participants could engage without distraction or outside pressure. Consistently, across all the organizations, personalization and community outreach proved to be the most effective means of gathering attendees. This approach was leveraged across a multitude of community-centric directives including, but not limited to, direct personalized correspondence, partnering with local clubs and initiatives, utilizing professional networks, and reaching out to community leaders.

While each organization invited Black men age 18 and older to participate, the conversations were not limited to these individuals. They also welcomed anyone interested in advancing the health, well-being, and social mobility of Black boys and men. In particular, MCCC and the Urban League expanded their geographic reach and age range to gather insights from participants across generations on the meaning of well-being for Black boys and men. They also invited people from diverse social groups and professional backgrounds to ensure a wide range of perspectives and experiences were represented.

Each organization facilitated four discussion sessions, except Johns Hopkins, which hosted a two-day hackathon or design-a-thon, approaches that draw on the nominal group process and Delphi strategies. The conversations took place from October 2024 through March 2025. Each session lasted about 90 minutes and included between 10 and 40 participants from the local community. All participants completed a demographic questionnaire, which allowed us to describe the population; a copy of the survey is included in the Appendix. Data were collected and analyzed using Qualtrics XM software. Each partner organization selected facilitators, typically local community members, to lead the discussions. The community conversations followed a semi-structured format based on an initial set of open-ended questions developed by the Brookings team. Facilitators were encouraged to tailor these questions to their community’s specific context, fostering relevant and inclusive discussions.

Each community conversation focused on a different theme:

- Community Conversation 1: Community building to identify definitions and reflections about well-being.

- Community Conversation 2: Examples and expressions of well-being for Black boys and men.

- Community Conversation 3: Identifying community leaders who are able to influence well-being for Black boys and men.

- Community Conversation 4: Discuss solutions and collaborations to enhance well-being for Black boys and men.

Recruitment and retention strategies

The community conversations took place in Little Rock from October to December 2024, in Baltimore on Jan. 31 and Feb. 1, 2025, and in Montgomery County from December 2024 through March 2025. To support attendance and participant retention, the four host organizations implemented engagement strategies before, during, and after the events. BBBSCA was the only facilitator to send regular email reminders about upcoming sessions, but all four hosts provided meals and refreshments for participants. Additional incentives included gift cards, attendance payments, and, in the case of the Urban League of the State of Arkansas, practical raffle prizes. To foster a sense of belonging and mutual respect, the hosts also sent follow-up emails thanking participants for their time and input, along with forms that allowed them to share additional comments they were unable to voice during the discussions.

CCP took a different approach to attendance and retention. Rather than hosting four separate sessions, the team consolidated its community conversations into a two-day hackathon, providing breakfast and lunch as well as travel reimbursements. Similarly, to strengthen community engagement, MCCC held its sessions at various locations across the county and ensured they were accessible by public transportation. Overall, BBBSCA, the Urban League, CCP, and MCCC thoughtfully addressed the needs of their communities through their attendance and retention strategies, creating welcoming environments where community members felt encouraged to share their perspectives.

In their approaches to retention, all four organizations incentivized attendance by providing meals and some form of monetary compensation. CCP offered both lunch and dinner during its sessions, along with $100 payments to participants. MCCC and BBBSCA provided gift cards, while the Urban League distributed raffle prizes. Additionally, CCP and MCCC took steps to ensure that transportation did not present a barrier to attendance. MCCC intentionally selected venues that were easily accessible by public transportation and offered convenient parking, while CCP provided transportation vouchers and parking reimbursements for its workshop site. Collectively, these incentives underscored each organization’s commitment to accessibility and participant convenience.

To maintain engagement with participants, the organizations used a combination of email correspondence and in-person meetings. BBBSCA sent frequent reminders, providing regular emails about upcoming sessions and emphasizing the value of each participant’s contributions. After each session, they followed up with thank-you emails. Similarly, MCCC conducted systematic follow-ups through emails and Q&A forms that allowed participants to share additional questions or insights after the conversations, and it also established a group text chat for ongoing communication. CCP and the Urban League continued engagement through follow-up meetings, which gave participants the opportunity to revisit previous discussions and raise new questions. CCP also provided additional compensation for participation in these sessions. Across all four organizations, these efforts fostered a sense of community and created welcoming environments that encouraged continued participation.

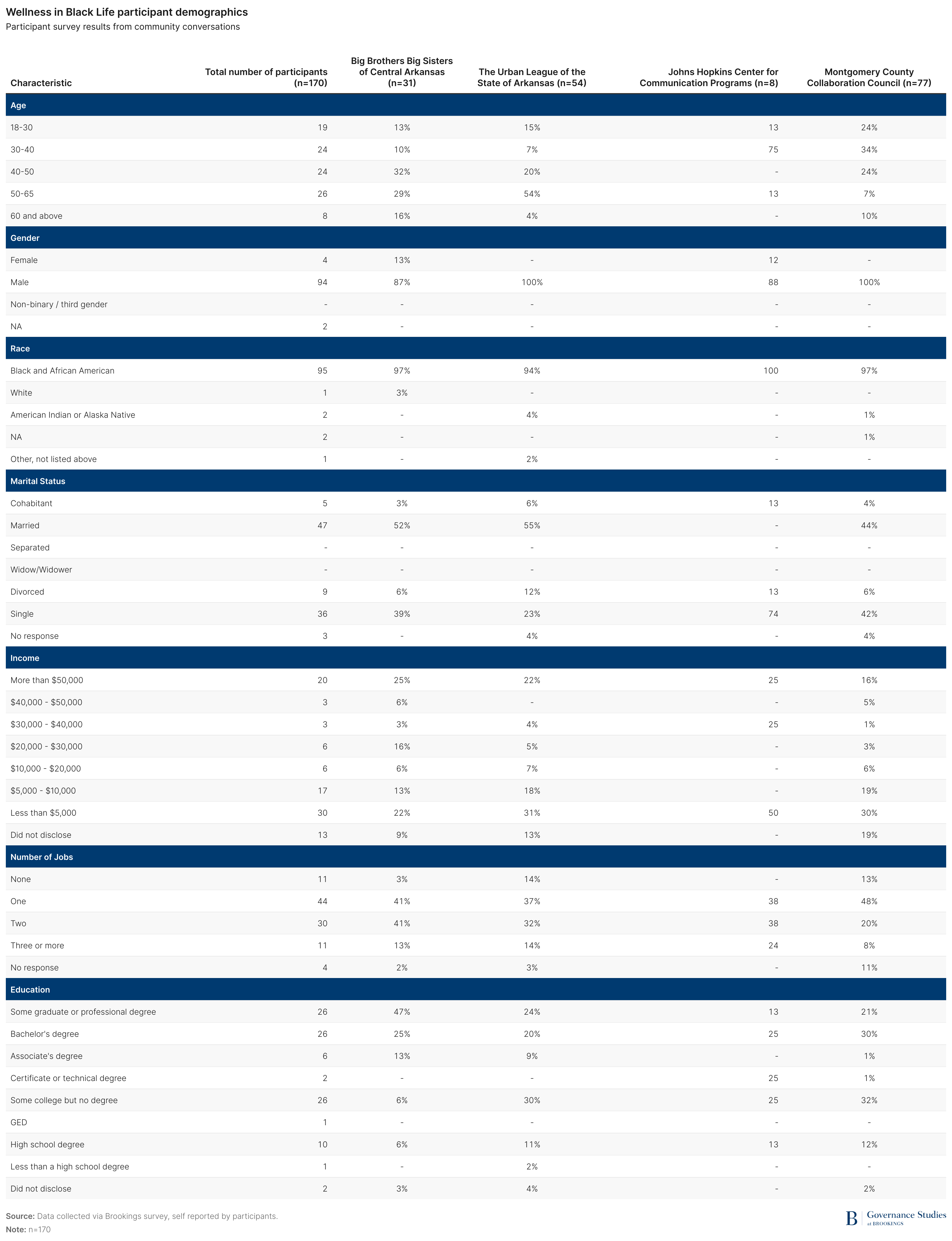

Click here to view the full table in a new tab.

Lessons learned from the community-engagement process

Social science and clinical research often face challenges with participant retention. In Little Rock, inconsistent attendance and scheduling conflicts led the Urban League of the State of Arkansas and BBBSCA to adjust their approach to facilitating community conversations across the four convenings. These adjustments included serving meals at the start of each event, sending reminder emails, and arranging convenient parking. Looking ahead, both organizations agreed to explore alternative logistics, such as hosting sessions earlier in the day or on weekends, to improve participant retention.

CCP experienced delays in IRB approval, which shortened its recruitment timeline. However, underscoring the importance of community partnerships, the team leveraged its connections in Baltimore City and its community engagement specialist to quickly spread the word. Similarly, BBBSCA noted challenges in recruitment and emphasized the value of strengthening community partnerships for future efforts, particularly by collaborating with Black universities and churches that have established and trusted social networks.

It is worth noting the MCCC concerns regarding personnel demographics. The race, gender, and ethnicity of both the conversation facilitators and the RPII project team raised questions about participants’ comfort in sharing their unique and often vulnerable experiences as Black men. While the RPII team addressed these concerns, MCCC’s feedback underscores the importance of community-led initiatives in creating safe and trusting spaces for participants.

Observations and implications

Highlighting the importance of fostering respectful and inclusive environments to promote meaningful dialogue, both the Urban League of the State of Arkansas and BBBSCA maintained consistent communication with participants, provided high-quality meals, and offered practical raffle prizes to show appreciation for participants’ time and insights. Looking ahead, the Urban League plans to deepen future conversations by sharing discussion questions in advance, teaching participants how policy affects their daily lives, and explaining how they can engage with local governments. These efforts aim not only to strengthen civic education and participation but also to build community members’ confidence in working with local officials to advance policies that support the well-being of Black boys and men.

CCP and MCCC highlighted the importance of leveraging long-standing relationships to engage multiple social networks effectively and build trust and credibility with community members. Emphasizing the ongoing value of these relationships, MCCC maintained open lines of communication with participants through its “show and prove” approach, consistently delivering results and following up on participants’ concerns and feedback. As Brookings and the host organizations remain committed to incorporating a range of lived experiences, reliable and transparent communication has proven to be a foundation for successful community engagement.

Final reflections

The social risks that Black boys and men face across the life course present unique challenges for identifying strategies to improve both the quality and longevity of a healthy life. Findings from this project emphasize sources of support that buffer Black boys and men against negative structural risk factors. Many of these supports, as discussed by participants, come from interpersonal supports—such as family and friends—and organizational resources, including faith-based institutions, organized sports leagues, and mentoring programs. These supports are shaped by broader structural and social factors and influence how Black men define well-being and envision improvements at different life stages. Participants explored how they want to lead efforts to enhance the quality and longevity of life for Black boys and men, seeking to create structures and processes that explain why some adolescent males develop positive identities and socially responsible behaviors while others do not.

Collaborating with the Urban League of the State of Arkansas and BBBSCA in Little Rock, MCCC in Montgomery County, and the Haywood Burns Institute and CCP in Baltimore played an essential role in recruiting participants for the Wellness in Black Life Project conversations. These organizations had already built strong relationships and trust within their communities, enabling them to tailor outreach and engagement strategies to the unique needs, values, and cultural contexts of each community. This approach fostered a supportive and inclusive environment where participants felt comfortable sharing personal experiences, offering insights, and being vulnerable without fear of judgment. Most importantly, partnering with local organizations promoted community ownership of the project and ensured that the work reflected the perspectives and needs of Black boys and men in these communities.

Appendix

Demographic survey

What organization are you speaking with today?

- The Urban League of the State of Arkansas

- Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Arkansas

- Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs

- Montgomery County Collaboration Council

Q1. What is your year of birth?

Q2. What is your race and/or ethnic identity? Select all that apply.

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Black or African American

- Hispanic or Latino

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- White

- Other, not listed above

Q3. Tell us your preferred gender identity.

- Male

- Female

- Non-binary / third gender

- Prefer not to say

Q4. What city and state were you born?

Q5. What is your current neighborhood zip code?

Q6. What is the name of the county of your primary residence?

Q7. What is the racial composition of your current neighborhood?

0%

10%

30%

50%

70%

100%

White

Black or African American

American Indian or Alaska Native

Asian

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

Middle Eastern or North African

Hispanic or Latino

Other

End of Block: Default Question Block

Start of Block: Tell us about your household

Q8. How long have you been living in your current residence?

- less than 1 year

- less than 5 years

- 5 – 10 years

- 10 – 15 years

- 15 – 20 years

- 20 – 25 years

- 25 – 30 years

- 30 – 35 years

- 35 – 40 years

- more than 40 years

Q9. Please describe your housing situation.

- Apartment

- Condo

- Townhouse

- House

- Other

Q10. How many people, including yourself, live full-time in your household? (Enter a number for adults and children)

Q11. How many people, including all adults and children, live full-time in your household? (Please include yourself and select/enter a number)

Please Enter a Number for Each Category

Spouse/Partner

Child/Children

Other family members

Friends

Roommates

Other

End of Block: Tell us about your household

Start of Block: Tell us about your marital and living arrangements

Q12. What is your current marital status?

- Cohabitant

- Married

- Separated

- Widow/Widower

- Divorced

- Single

End of Block: Tell us about your marital and living arrangements

Start of Block: Education

Q13. Tell us about your current education status

- Not a student

- Full-time student

- Part-time student

- Other

Q14. What is your highest degree of educational attainment?

- Less than a high school degree

- High school degree

- GED

- Some college but no degree

- Certificate or technical degree

- Associate degree

- Bachelor’s degree

- Some graduate or professional degree

Q15. If you have completed some college or some education after high school or GED how did you finance your education? (select all that apply)

- My own savings

- Savings and contributions from others

- Work study (including federal work study)

- Loans

- Scholarships

- Others

End of Block: Education

Start of Block: Tell us about your employment and earnings

Q16. What best describes your current employment situation?

- Self-employed, full-time for pay (includes independent contract work)

- Self-employed, part-time for pay (includes independent contract work)

- Work full-time for pay

- Work part-time for pay

- Unemployed, looking for work

- Unemployed, not looking for work

- Disabled, not able to work

- Stay at home parent or spouse

- Full-time caregiver for a family member

Q17. How many total jobs do you currently have?

- None

- One

- Two

- Three or more

Q18. In what sector are you working (for your primary job)?

- Private sector

- Government sector

- Self-employed

- Non-profit sector

- Unpaid family sector

Q19. Please tell us what benefits are associated with your current job (primary job)?

- Health

- Dental

- Vision

- Disability

- Retirement

- Paid sick leave

- Paid vacation

- Flexible work schedule

- Family leave

- Childcare

- Education

- Disability pay/disability insurance

- Other

- None

Q20. On average, how many hours do you work per week?

- None

- 10 or less

- > 10 to 20

- > 20 to 40

- > 40

Q21. Do you have a consistent work schedule every week?

- No

- Yes

Q22. Which category best describes your monthly income?

- less than $5,000

- $5,000 – $10,000

- $10,000 – $20,000

- $20,000 – $30,000

- $30,000 – $40,000

- $40,000 – $50,000

- More than $50,000

- I prefer not to say

Q23. Thinking about your main job how are you paid?

- Salaried

- Hourly

- Other

Q24. Thinking about the next month, how concerned are you that you and your family might experience difficulties with each of the following?

Not at all worried

Not too worried

Somewhat worried

Very worried

Having enough to eat

Being able to work as many hours as you want

Being able to pay your rent or mortgage

Being able to pay your gas, oil, or electricity bills

Being able to pay your debts

Being able to pay for medical costs

End of Block: Tell us about your employment and earnings

The Brookings Institution Wellness in Black Life Indicator Survey

If republishing survey results:

This survey originally appeared as part of the final report of the Wellness in Black Life project by The Brookings Institution. It is republished here with Brookings’ permission.

If redoing the survey with a different sample:

This survey and its methodology have been developed by the Brookings Institution as part of the Wellness in Black Life project. They are being repurposed here with Brookings’ permission.

Q1. This project’s focus is on advancing the well-being of the Black community here in [Insert city name]. In your own words, how would you define “well-being,” what words come to mind that help define this for you? [Open Ended]

Q2. Which of the following are the most important to you when you think about the well-being of the African American community / your community?

- Affordable housing

- Quality schools

- Jobs that pay affordable wages

- Access to healthy and affordable food

- Low crime rate

Q3. Which community do you currently live in?

[These were the locations for this study. If replicating this survey please insert your own locations.]

- Little Rock, AR

- Montgomery County, MD

- Baltimore, MD

Q4. What are the most important issues that you want local officials to address that you think can help improve the well-being of Black men and Black boys? Select up to three.

- Affordable housing

- Affordable childcare

- Reducing homelessness

- Impacts from climate change (wildfires, droughts, and flooding etc.)

- Universal, highspeed, affordable internet

- Clean up pollutants and environmental threats

- Rising cost of living

- Reducing government spending

- Police reform

- Supporting K-12 education

- Improving and expanding public transportation

- Creating jobs with better wages

- Health care costs

- More funding for community-based organizations

- Address crime / make our community safer

- Providing services for mental health and substance abuse

- Something else

Q5. What do you think are the three biggest problems or challenges facing Black men and Black boys’ well-being?

- Car break-ins and robberies

- Home break-ins and robberies

- Child abuse

- Disorderly conduct / public intoxication / noise

- Domestic violence

- Discrimination against Black men and Black boys

- Drunk driving / driving under the influence (i.e., alcohol or drugs)

- Drug abuse (e.g., manufacture, sale, or use of illegal / prescription drugs)

- Fraud / identity theft

- Gang activity

- Gun violence

- Hate crimes

- Homelessness

- Homicide

- Mugging

- Physical assault

- Prostitution

- School safety (e.g., bullying, fighting, or weapons)

- Sexual assault / rape (adult)

- Traffic issues /residential speeding

- Underage drinking

- Vandalism / graffiti

Q6. Which of the following are most important to you to make your community safe and vibrant? Select all that apply. [RANDOMIZE]

- Access to safe and clean public parks and spaces

- Affordable housing

- Quality schools

- Jobs that pay affordable wages

- Access to healthy and affordable food

- High quality transportation infrastructure / public transportation

- Low crime rate

Q7. Overall, how would you rate your community as a place for Black men and Black boys to live?

Excellent …………………………………………………………………. 1

Very good ……………………………………………………………….. 2

Good ………………………………………………………………………. 3

Fair ………………………………………………………………………… 4

Poor ……………………………………………………………………….. 5

Q8. How much influence do you think Black men and Black boys have on the decisions made to advance the well-being of the community?

- Too much influence

- The right amount of influence

- Not enough influence

- Don’t know

Do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

Q9. If I work with other Black males, we can make our community a safer place to live and work.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Q10. If I work with other members of my community, we can work together to advance the well-being of Black men and Black boys.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Q11. How concerned are you that you might have to move away from your community because housing and / or rent prices are getting too expensive?

- Very concerned

- Somewhat concerned

- Not that concerned

- Not at all concerned

Q12. How much do you worry about crime and safety where you live?

- A great deal

- Some

- Not very much

- Not at all

Q13. Compared to one year ago, do you feel safer or less safe living in your community now?

- Felt safer living in [insert location here] LAST year

- About the same

- Feel safer living in [insert location here] NOW

Q14. Please indicate if the following should be a high priority or low priority for Black men and Black boys in your community?

- Addressing police brutality

- Reducing mass incarceration

- Opposing same-sex marriage

- Raising the minimum wage

- Restricting access to abortions

- Addressing climate change

- Addressing domestic violence / sexual violence

- Reducing the number of liquor stores in the [racial group] community

- Stopping voter suppression

- Reducing crime

- Increasing funding for public schools

- Supporting immigrant rights

Very Low Priority …………………………………………………….. 1

Low Priority …………………………………………………………….. 2

High Priority ……………………………………………………………. 3

Very High Priority ……………………………………………………. 4

Q15. Where you live, which of the following HEALTH SERVICES, if any, do you want to see more of (make more widely available) for Black men and Black boys? Select all that apply. [RANDOMIZE]

- Basic medical care

- Mental health care

- Addiction / substance abuse services

- Specialty care, like dentists

- Holistic medical care like acupuncture

- Vocational education

- Access to youth programs (resident and non-resident)

- Fatherhood programs and services

- None of these

Q16. Which of the following EMPLOYMENT SERVICES, if any do you want to see more of (make more widely available) where you live for Black men and Black boys to access? Select all that apply.

- Obtaining a GED

- Job search assistance / training

- Keeping current or maintaining job skills

- Vocational training

- None of these

Q17. Which of the following FAMILY / CHILDREN’S SERVICES, if any, do you want to see more of (make more widely available) where you live for Black men and Black boys to access? Select all that apply.

- More preschool options

- More K-12 school options

- More after-school activities

- More community programs for children when schools are closed

- More summertime programs

- More child care / daycare options

- More athletic programs for boys

- More STEM programs

- None of these

Q18. Over the past year, would you say that the economic well-being of Black men in this country has, overall, gotten better or worse as a result of the Trump administration’s policies?

- A lot better

- Somewhat better

- Same / no change

- Somewhat worse

- A lot worse

Q19. Given the current political climate, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the prospects of Black boys achieving upward mobility in this country?

- Optimistic that Black boys will achieve upward mobility

- Pessimistic that Black boys will achieve upward mobility

Q20. Have you noticed more Black men in your community having to do any of the following to manage their financial situation during the past year SPECIFICALLY because of price increases and rising costs of living? Select all that apply.

- Borrowed money from friends or family

- Applied for a loan from a bank or credit union

- Borrowed money from a payday or title loan company with a high-interest rate

- Used up all or most of their savings to help pay for their family’s expenses

- Skipped a monthly car, rent, or mortgage payment

- Postponed or cut back on health-related expenses

- Postponed or quit education / career-related expenses

- Moved or changed my housing situation

- Postponed or cut back on family or children’s activities

- Relied on food banks / pantries and / or cut back on meals to manage cost of food

- Spent less time with their children / family on entertainment

- Cut back or withdrew their child from child care due to costs

- Quit their job or reduced hours because they could not afford child care

- None of these

Do Black men and boys have access to each of the following where you live?

Q21. Safe parks and public spaces to exercise in the community

- Yes

- No

- Not sure / don’t know

Q22. Access to healthy and affordable food

- Yes

- No

- Not sure / don’t know

Q23. Health care facilities near me that provide the services I need

- Yes

- No

- Not sure / don’t know

Q24. Clean air and drinking water

- Yes

- No

- Not sure / don’t know

Q25. Reliable and high-quality public transportation

- Yes

- No

- Not sure / don’t know

Q26. To what extent (how much) does local law enforcement where you live develop relationships with community members (residents, organizations)? For example, walking around the neighborhood to get to know people who live in the community.

- Not at all

- A little

- Somewhat

- A lot

- To a great extent

Q27. How often do you believe that local law enforcement where you live treats Black men and Black boys with dignity and respect?

- Always

- Usually

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- Don’t know

Q28. Which of the following emerging careers do you think Black men and boys need training opportunities for in order to be competitive for the jobs of the future?

- Energy (clean energy jobs, solar power, etc.)

- Health care industry

- Artificial intelligence / AI

- Finance and banking

- Construction

- Science / technology / engineering

- Data science and virtual data

Q29. Which of the following actions can Black fathers and boys take to help improve their overall well-being?

- Make sure to register and vote to make their voices heard

- Invest in themselves through education and workforce / career training

- Work with others in community organizations to push for their collective goals

Facilitator Discussion Guide

Ground rules:

- There are no right or wrong answers to the questions

- We want to hear what you feel and think about (your topic) and related issues

- It’s ok to disagree with something that is said

- Be respectful of other’s opinions

- You don’t have to respond if uncomfortable

- There are no unimportant or silly ideas

- We want you to be comfortable, so feel free to get up for a drink or to visit the restroom during the discussion

This discussion will be audio recorded so that the team can have the tapes transcribed with accuracy. The audio recording will be reviewed by the team to better understand your responses. If you feel uncomfortable with the discussion, you may discontinue or refuse to be audio recorded. If you have questions, please do not hesitate to ask.

Names: Please say your name before speaking. This will make it easier for us to know what you said when we go back and listen to the recordings. Also, when referring to someone else in the group, please use the name printed on their name tag. Because we are recording, it is very important for only one person to speak at a time. So, if I cut you off to let someone else speak, please don’t think that I am being rude. I am only directing the discussion so that we can hear what both individuals have to say.

Session length – 90 minutes

Focus group – Session 1: Building rapport and understanding shared definitions around well-being

1) How would you define well-being?

- Discuss the artifact

- Create a word cloud

- Recap (after the artifact discussion)

2) What challenges, barriers, or narratives hinder or interfere with how Black men and boys define well-being?

3) What current support systems exist for Black men and boys?

- How do these systems help counter negative narratives and barriers

Focus group – Session 2: Expressions of well-being in the lives of Black men and boys

1) Icebreaker: Rose / bud / thorn of their week (open/non-specific)

2) Facilitator does reflections/recap of last conversations

For recap:

- Summarize barriers

- Summarize supports

- Review definitions, ideas, and new language for well-being

- Transition: “We’ve talked about well-being in your community. How does this apply specifically to Black boys and men?”

3) Application to Black boys and men – describe the topic for the conversation and outline the questions that follow

4) Exploring people, places, and expression

- Describe people (networks) that allow Black boys and men to feel free, vulnerable, and safe

- When are Black boys and men most likely to be heard and free to express themselves?

- Describe places or outlets that allow Black boys and men to be free, vulnerable, and safe

5) Healthy environments and quality of life

a) In what ways can these people, places, or outlets be used to help Black boys and men achieve a high-quality life?

b) What does a healthy environment for them look like?

- Probe: education, safety, joy, happiness, success, thriving (take the words in the word cloud and apply them specifically to Black boys/men)

- Idea: make another word cloud activity for the people/places questions

6) Sub-question: What other structures need to be in place to help achieve this?

7) How would you describe Black boy/men joy?

Focus group – Session 3: Well-being in the community for Black men

Icebreaker: Rose/bud/thorn of their week (or something else)

Facilitator recap

- Three word clouds – definitions, people, places

After thinking about definitions, people, places

- Question (word cloud for this – separate for boys and men): a) What/where/who are the advocates, voices to take up concerns to enhance well-being about Black boys and men?

- Probe/ follow-up: What are the accountability structures/follow through?

- What is the role of policy leaders? [For this question, make a distinction between boys and men]

Question: We’ve talked about community structures, networks, and organizations. We do recognize that there are other factors that contribute to well-being, so we want to spend a little time discussing the impact of climate, environment, and natural disasters. As we know, the climate is changing, becoming hotter and with more violent weather. Some of that can dislocate families. In addition, the need to adapt to climate change is changing the types of jobs that are available. There are more jobs that use technology. How do these ideas of weather dislocation, heat, and changes in the types of jobs available affect Black boys and men?

Question: What more needs to be done to ensure that Black boys and men in your community experience well-being? Again, we welcome all ideas and are not judging any of those ideas here.

Focus group – Session 4: Developing solutions. How collaboration is needed to accomplish the well-being of Black males in their community

Icebreaker: Rose/bud /thorn of their week

Reflection: Create word clouds.

- What’s missing from the word clouds?

- What other solutions or strategies can you suggest?

- What examples of policies or programs come to mind?

- How can programs and policies be shaped by these ideas?

Activity:

- Update the word clouds with the above responses.

- Develop a list of strategies.

- Use a Qualtrics poll: Rank your top three choices to prioritize issues, recommendations, and strategies.

After the break:

- Present the three most common themes.

- Facilitate discussion on these three focus areas.

Discussion prompts:

- What resources are needed to support these strategies?

- If we were to track and monitor progress, how should we measure it?

Focus group – Session 5: Sharing the results. Definitions we gathered (indicators and tools)

After the statement has been established, end the recording, and thank everyone.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Wellness in Black Life team extends sincere thanks to the following individuals for their contributions and support throughout this project: Gabriel R. Sanchez, Carly Bennett, Kwadwo Frimpong, Jane Kaniecki, and Sade Cole. We are also deeply grateful to our interns—Patrick Edwards, Erika Xu, Meilyn Farina, Zachary Affeldt, Calvin Bell, Treasure Evans, Kaitlyn Jung, Ella Tummel, and Karishma Luthra—for their support during this process.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).