HOW WE RISE

Executive Summary

Across the U.S., economic mobility is frequently linked with geography. Some places afford poor children the opportunity to do better economically than their parents did, and other places do not. Social networks, providing access to support, information, power, and resources, are a critical and often neglected element of opportunity structures. Social capital matters for mobility.

We undertook this research project to understand and compare the social networks of groups of diverse individuals in three U.S. cities (Racine, WI; San Francisco, CA; and Washington, DC) relative to job, stable housing, and educational opportunities. These three cities were selected because of their very different economic mobility profiles: San Francisco is a high-mobility city, Washington is a city of moderate economic mobility, and Racine is a low-mobility city.

We analyzed over 30,000 interpersonal network connections across all three cities, drawing on rich data from 254 interview participants: 107 in Washington, 96 in San Francisco, and 51 in Racine. Interviews were conducted between May 15, 2020, and July 24, 2020. These networks were then evaluated for size (i.e., number of people), composition (i.e., range of connection types, such as familial or professional) and strength (i.e., the value of connection as a source of assistance). We compared social networks by demographic group, especially among race, income, and gender. In particular we assessed networks in terms of their value for access to opportunities and resources in three domains: jobs, education, and housing.

Social capital matters for mobility.

In an initial effort to understand how the network characteristics differed by demography and geography, we investigated the topic-specific network data by city and the following demographic characteristics of the participants: age, race, gender, educational attainment, individual income, and neighborhood of residence

After our initial investigation of these social networks, we determined that race and gender were the most important explanatory characteristics in Racine and Washington, and that race and individual income (either below $50,000 or $50,000 and above, annually) were most important in San Francisco.

For our final analysis, we explored how racial, gender, and income dynamics influence the formation and function of social networks—particularly those we determined to be linked to economic mobility. We identified how topic-specific and total deduplicated network size differed by participant characteristics to examine if participants had specialized networks (e.g., specific people serve topic-specific roles) or general networks (e.g., the same people are consulted for all topics). We additionally investigated the challenges that participants experienced by city and demographic characteristics to understand how challenges differ by group and interact with social mobility.

We determined that race and gender were the most important explanatory characteristics in Racine and Washington, and that race and individual income were most important in San Francisco.

Across all three cities, our main empirical findings were:

- Race is the most important and consistent differentiator of social networks.

- Across all three cities, white participants had the most racially homogenous networks relative to jobs, education, and housing. In Washington, DC, networks were fairly racially homogeneous for all groups except Latina females, and were most racially homogenous for white men in Washington (97 percent white). In Racine, whites had more racially homogeneous networks than Blacks, with white males having the most racially homogenous networks.

- Among the three cities, San Francisco stands out as having the least racially homogenous social networks, although whites in San Francisco are more likely to have the most racially homogenous social networks than are other racial groups. In San Francisco, homogeneity differed by each topic, but was lower than in Washington and Racine. Overall, whites of both income categories (both below $50,000 as well as $50,000 and above) and Asians with incomes of $50,000 and greater had more racially homogenous networks than other groups. Latinos with incomes of $50,000 and greater had less homogenous networks than other groups, though the sample size is small.

- Across all three cities, Black males tended to have small networks for jobs, education, and housing. In Washington and Racine, their networks were generally racially homogenous, consisting of a majority of network members that were also Black. Their networks did include both males and females, however. Black males tended to cite challenges related to income and job stability, and mentioned race, age, and money as factors that contribute to these challenges.

- Job, education, and housing networks were composed primarily of friends, family, and colleagues (especially in job networks). In some cases, participants named partners, advisors or mentors, service providers (e.g., social workers, nonprofit staff), or for-hire counselors or realtors as members of their networks. Friends and family typically accounted for approximately half or more of an individual’s given social network.

- Outside of family, job, education, and housing networks were primarily formed through work, education settings (college or K-12 schooling), and community activities. Since social networks can change over time, it may be important to focus on these three settings for adjusting social networks for specific groups. There were some differences in each of the cities, with participants in Washington and Racine reporting educational and work settings as the main avenues for meeting people in their networks who were not family members; in San Francisco, community activities were an especially significant source of meeting people.

- Finally, we found that social networks vary in terms of size and composition across different groups and cities. Participants in Racine had the largest total network (5.94 people) and topic-specific networks. Washington and San Francisco had the same total network size (4.99 people). Washington had the smallest job and housing networks, while San Francisco had the smallest education networks. Members of participants’ housing and education networks overlapped the least.

Below are our main empirical findings. A full methodology and further technical details are available here.

City-Specific Results

Washington, DC

We focus on race and gender as the variables of comparison for network differences in Washington, DC. There are notable differences in characteristics for individuals living in different neighborhoods by race. There are also disparities in home ownership rates and property values, worsened by policies such as restrictive zoning that have disproportionately affected communities of color and created significant wealth gaps.

- Among racial groups with 10 or more people in the sample, white women had the largest networks, followed by white men, Latinas, Black women, and Black men.

- Additionally, white participants were likely to have people of the same race in their job network, which may help them access individuals in professional leadership roles. Black participants were also likely to have high proportions of their networks like them in terms of race. Since people of color are underrepresented in executive positions and leadership roles, this may limit the ability of people of color with racially homogenous job networks to access individuals in professional leadership roles.

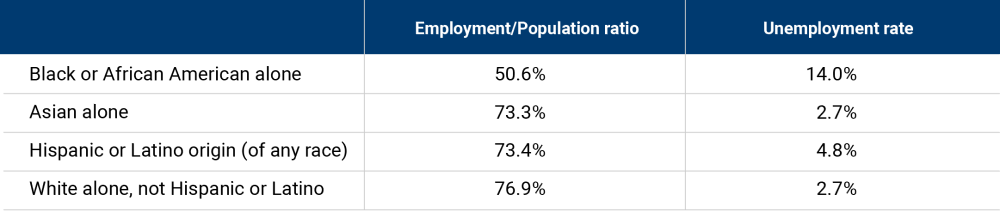

The table below shows the employment to population ratio and the unemployment rate for workers in Washington by race. The lower employment rates and higher unemployment rates among Black residents gives context to the smaller size of job networks.

Employment and Unemployment Rates in Washington, DC by race

- White respondents were more likely to meet nonfamily members in their education networks connections through college or K-12 school, highlighting the importance of school as a foundation for network building. Education networks were generally homogeneous in terms of race, especially for white participants.

In 2019, the high school graduation rate in Washington, DC, public schools was 64 percent for Black students, 57 percent for Hispanic students, and 92 percent for white and Asian students. Since school is an important foundation for network building, the low graduation rates among Black and Hispanic students indicates that the public school system is poorly serving them in terms of allowing them to build strong education networks.

- Across the sample, housing networks were relatively small. Black male participants tended to have the smallest housing networks, while white males had the largest average housing networks. Small housing networks may limit access to information about housing, such as location, safety, cost, and community features, or resources for securing new housing.

It is no surprise that housing networks differ by race; the city’s demographics have been changing over the past 50 years, and gentrification has significantly affected Washington. Approximately 36 percent of the population lives in an area where neighborhood displacement is occurring. Population centers for Black communities have become less dense within the District as an increasing number of Black residents have moved to the suburbs in Prince George’s County, MD. At the same time, population centers for other communities, such as Hispanic, Asian, and white residents, have grown inside the District.

- A large proportion of Black men and Latina women identified six different factors that contribute to their challenges: age, race, gender, being unprepared, geography, and money. In comparison, a large proportion of white women identified gender as the only factor contributing to their challenges.

San Francisco

San Francisco has a higher-than-average median income, but inequality is prevalent. The median income in San Francisco households is $112,376, almost double the national average, but income inequality as measured by the Gini index is higher than the national average. Cost of living in the city is also high. Approximately 60 percent of the population of individuals aged 25 years and older hold a postsecondary school degree. One study found that San Francisco was the most intensely gentrified city in the country from 2013 to 2017, a process that has negatively impacted racial minority and low- to moderate-income populations.

For these reasons, analysis of data from interviews with participants in San Francisco focuses on understanding differences in job, housing, and education network characteristics based on race and income.

- Job network size among respondents in San Francisco tended to be larger for those with individual incomes of $50,000 or greater than those with incomes of less than $50,000. Asian respondents tended to have larger job networks than white, Black, and Latino respondents, which may indicate better access to information or resources about jobs. Respondents with an income of $50,000 or more were more likely to meet their job network through work. This may indicate the importance of work as a setting for forming professional connections, especially in San Francisco, where college and K-12 schooling were not as common an avenue to make connections for job networks as compared to Washington.

- Respondents with incomes of $50,000 or higher tended to have larger education networks than those with incomes of less than $50,000, which highlights how access to educational resources is tied to income. Proportions of respondents in both income ranges met nonfamilial education network members through community activities, which may signal the importance of these activities in creating networks.

- Those with an individual income of $50,000 or more tended to have more members in their housing networks. Family and partners made up large proportions of respondents’ housing networks. Respondents with incomes less than $50,000 were more likely to have service providers, such as a social worker or case manager, in their housing networks. This illustrates that service providers may be beneficial in supplying housing information and resources for lower-income individuals.

- Community activities were mentioned as means through which networks in San Francisco are formed, more so than in Washington and Racine. This highlights the potential value of community resources in providing individuals with information and resources relevant to accessing job, education, and housing opportunities, especially for lower-income residents and non-Asian people of color, who tended to have smaller networks. Policy should focus on increasing the accessibility and quality of such activities, such as community networking opportunities, by sponsoring city events located in central areas that are accessible via public transit and recruiting participants across job sectors, education levels, and income groups.

- More than 30 percent of the whole San Francisco sample identified age, money, and race as significant challenges.

Racine

Examining race in Racine is particularly important as racial disparities are stark both in the city and Wisconsin as a whole. Racine county has consistently been rated one of the worst counties in the country for Black or African-American individuals (only behind Milwaukee, WI), considering factors such as education, income, health outcomes, incarceration rates, home ownership, and unemployment levels. Racine has a long history of racial discrimination through redlining and housing inequity. Blacks and Native Americans are overrepresented in Wisconsin’s growing prison population. Black men are disproportionately affected: A 2013 study found that one in eight Black men of working age in Wisconsin are incarcerated, the highest rate in the country and about twice the national average rate. The significance of this intersection of gender and race and its effect on life situations in Racine informed our focus on these two variables in analyzing impact on network differences in the sample from the city.

- White respondents tended to have larger job networks than Black respondents. In Racine, the unemployment rate for Black residents was 11.6 percent in 2018 compared to 5.6 percent for white residents, which gives context to the difference in the size of job networks by race. White males had larger job networks than white females, but Black females had larger job networks than Black males (though only a small number of white males and Black males were included in the sample and may not be representative). Non-white participants were more likely to include advisors or mentors in their job networks.

- Many respondents across the groups had met their nonfamily job network members through work. White respondents were more likely than Black respondents to meet nonfamily network members through school.

K-12 schools and colleges are important settings for network formation, but they seem to be less accessible to people of color in Racine. For example, Blacks and Hispanics account for the largest share of suspensions and incidents that resulted in disciplinary actions. About 85 percent of Black students were involved in incidents that resulted in disciplinary action in the 2018-2019 school year, compared to 19 percent of Hispanic students and 13 percent of white students. Efforts to combat disproportionate suspension and expulsion rates include the Student Expulsion Prevention Project, which prepares private attorneys to represent students at expulsion hearings, and teacher training to increase awareness of the underlying causes of some student behaviors, including poverty, trauma, and substance abuse. Local education policy should target the reduction of racial discrimination in access to and quality of education.

- White participants tended to have larger housing networks than Black participants. More Black participants met nonfamilial housing network members as service providers, such as realtors or city employees.

- The majority of Black females identified the factors of race, money, and where they live/geography as their biggest factors that contribute to challenges; white women only identified money as a factor.

Policy Opportunities

Social networks are important conduits for economic mobility. Our work demonstrates that, in the U.S., race is an overarching force shaping social networks and the resources within these networks. Although we have studied four cities in the How We Rise series to date—Washington, DC, San Francisco, CA, and Racine, WI, in this report, as well as Charlotte, NC in a separate paper—three findings really stand out: relative to job, housing, and educational opportunities, white men tend to have the most racially homogenous networks, Black men have the least robust networks, and participants in cities with lower economic mobility appear to have the most racially homogenous social networks. San Francisco, a high-mobility city with a very small Black population, had the least racially homogenous social networks relative to jobs, education, and housing.

White men tend to have the most racially homogeneous networks, Black men have the least robust networks, and participants in cities with lower economic mobility appear to have the most racially homogeneous social networks.

In areas with low economic mobility, we have noticed that segregated residential patterns, discriminatory K-12 school climates that particularly disinvest in Black boys, and overall lower rates of employment among communities of color consistently accompany the social networks we have described.

What is be done? We do not offer a blueprint for building social capital; however, as we previously recommended in our analysis of social mobility networks in Charlotte, we do suggest some potential paths forward for these cities. Most important, three commitments must be made by each city’s civic, business, and political leaders:

- Candidly engage with the racial dynamics of the city.

- Work collaboratively across racial lines to identify who is accountable for equity goals.

- Identify and execute on policy areas where the greatest racial equity gains can be achieved in the next three to five years.

As a result of authentically acting on these commitments, a series of policy goals and approaches could emerge. The city could, for example:

- Set a goal to drive down school suspension and incarceration rates among Blacks compared to those of whites.

- Develop a racial equity plan for the city that articulates measurable, highly impactful equity goals.

- Transition away from a juvenile justice system and school suspensions.

- Support young Black and Latina mothers, measuring success by rates of maternal mortality.

- Invest heavily in a college savings account for all kindergartners in public schools and make additional payments for lower-income students over time.

Most importantly, these equity goals should be driven by those who are least advantaged. Each city’s divisions, not least in social networks, reflect choices made in the past; choices that today’s leaders and residents in each city can and should make differently, in order to create a true horizon community.

This report is part of The Brookings Institution’s How We Rise project, a larger series of research and analysis that helps to explain the dynamics of social connections and the policy solutions that intentionally focus on the social network determinants of economic mobility and equity.

The How We Rise project is part of the Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative, Brookings’s cross-program effort focused on issues of equity, racial justice, and economic mobility for low-income communities and communities of color.