The Hamilton Project’s mission is advancing opportunity, prosperity, and growth. Promoting a strong and innovative education sector is at the core of this mission. Access to high-quality education enables Americans to gain the knowledge and skills needed to achieve in the classroom and succeed in the workforce. Yet, the education system has fallen short of providing high-quality educational opportunities to all students and so the goals of the education sector are not being met. Within the United States there is stagnating student achievement on standardized test scores and slow growth in degree attainment as well as large gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged students on measures of student achievement and degree attainment.

In the past 25 years the idea of charter schools as a means for public education system innovation has emerged from a wide variety of sources. In 1988 the president of the American Federation of Teachers, Albert Shanker, spoke in support of a mechanism that would give teachers the ability to submit a proposal to create a new publicly funded school that was free of certain regulatory constraints in order to try innovative approaches to teaching and test their impacts. In 1990 the Brookings Institution published John Chubb and Terry Moe’s Politics, Markets, and America’s Schools. This book recommended rebuilding the American education system based on principles of market competition and deregulation, and suggested that, through parental choice and school autonomy, student achievement would improve.

Beginning in the 1990s with Minnesota, states started to pass laws to allow the establishment of publicly funded charter schools. In general, charter schools receive public funding the way traditional public schools do, but operate independently of local school boards or superintendents. Charter schools have used this autonomy in a variety of ways to structure their schools and classrooms innovatively. As Roland Fryer discusses in a Hamilton Project policy proposal, such practices include changing human resource practices, making instruction data driven, developing intensive tutoring programs, increasing the amount of time spent in the classroom, and setting high expectations.1 The second leg of charter school policy is the market hypothesis: providing access to charter schools will improve education through competition. The result of competition may be that all schools—charter and regular public schools alike—will improve because they face an increased threat of losing enrollment if they do not perform adequately. For charter schools to encourage school choice and competition, students must have reasonable access to them.

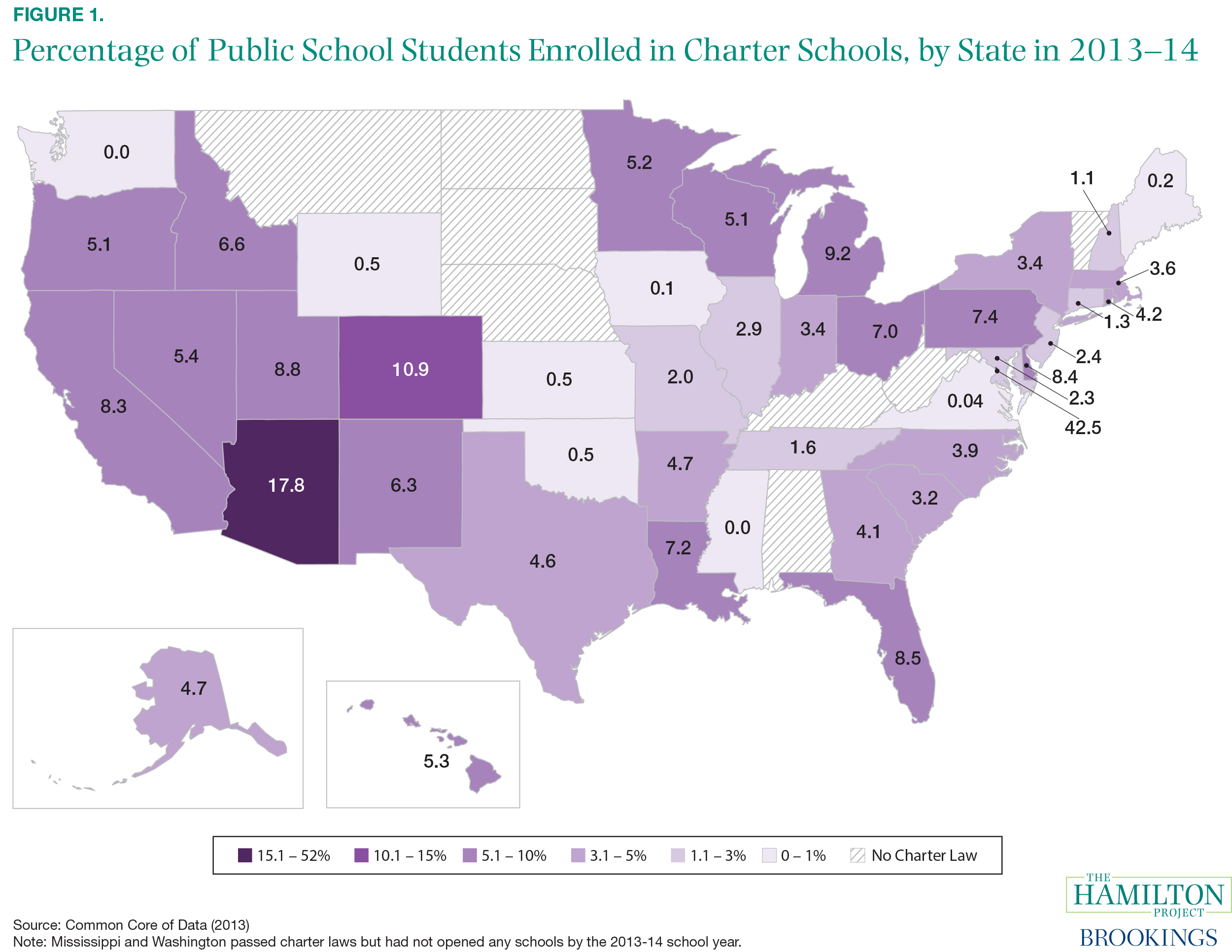

As of the 2014-15 school year, 42 states and the District of Columbia had passed charter laws and 6,648 charter schools were operating nationwide.2 In 2013–14, 5 percent of public school students nationwide attended a charter school, which is more than double the share 10 years earlier.3 As shown in figure 1, there is wide variation in charter school enrollment across states. Arizona has the highest share among states with nearly 18 percent of its public school students enrolled in charter schools.4 Several states, including Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Virginia, and Wyoming, have charter schools, but less than 1 percent of students attend them.

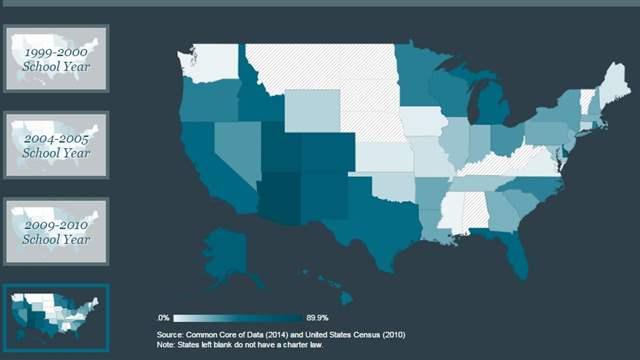

In this economic analysis, we look at access to charter schools at a market level to measure the share of students who live close enough to a charter school as to have the choice to attend a charter school or not. Nationwide, 32.4 percent of students in states have local access to a charter school—defined as living in the same zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) as a charter school.5 This analysis documents that access to charter schools has grown over the past two decades and access to charter schools differs dramatically across states. While the vast majority of states—41 in all—have at least one charter school, states and localities vary widely in the extent to which students have access to charter schools and thus school choice. An accompanying interactive state map breaks out access by year and race/ethnicity.

1 Fryer’s research is based on urban charter schools. There are also charter school policies and practices adapted to students who live in suburban and rural areas, such as deploying online education to make up for distance from school facilities. There are also charter schools that are organized to serve particular students, such as teen mothers or ex-offenders.

2 Including 231 virtual charter schools, the total is 6,879 charter schools. We exclude virtual charter schools from the access portion of our analysis due to our focus on geographic location and lack of classification for virtual schools prior to the 2013-14 schoolyear in the Common Core of Data. On March 19, 2015, Alabama passed its first charter law.

3 The Common Core of Data includes enrollment data only through school year 2013–14, but provides other relevant school data through 2014–15. As a result, in this analysis the enrollment graphs (figures 1 and 4) are for 2013-14, while the most recent school year for the access graphs (figures 2 and 3) is 2014–15.

4 The District of Columbia has 43 percent of students enrolled in charter schools, but is not a state.

5 This access measure does not address whether there are enrollment slots available in the charter school. There is no systematic information available on seats available or whether charter schools are operating at capacity.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).