Russian President Vladimir Putin has seemingly weathered an extraordinary challenge to his leadership after his one-time protégé and leader of the Wagner mercenary group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, agreed to call off his armed uprising against the Russian military establishment. But how this crisis will impact Putin’s standing at home – and whether he will face subsequent challenges to his rule – remain open questions. The risks for Beijing are high, too, given Chinese President Xi Jinping’s investment in relations with Putin, as well as uncertainty surrounding Russia’s trajectory, the war in Ukraine, and the broader strategic environment in China’s backyard.

What’s at stake for China?

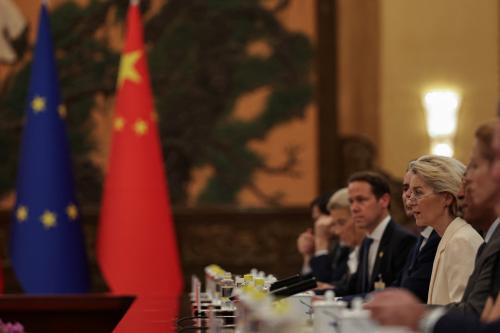

Under Xi’s rule, Beijing has invested heavily in its relationship with Moscow. It has looked to the latter as its chief partner in counterbalancing against the United States and its allies and weakening what both states see as a “Western-centric” global order. Xi and Putin have close personal ties, having met dozens of times over the last decade and directly overseen the inking of their countries’ so-called “no limits” partnership.

Beijing’s first-order concerns likely revolve around the potential for domestic upheaval in Russia, with which it shares a more than 2,600-mile border, to spill over into China or to destabilize its immediate neighborhood. And just as American officials have been closely tracking Russia’s nuclear posture since the crisis, Chinese leaders are also likely anxious about the risk of loose Russian nukes and the threat this would pose to China’s security.

The Wagner rebellion has likely raised questions about whether China’s strategic alignment with a weakened Russia may turn out to be a net burden rather than a plus to China’s interests.

Beyond immediate security concerns, there is undoubtedly deep apprehension in Beijing about how this crisis will impact Russia’s trajectory, already beleaguered by its war of aggression in Ukraine and extensive international sanctions. Over the last year and half, China has taken a deep hit to its global image and its relations with Western states by choosing to double down on its relationship with Moscow. The Wagner rebellion has likely raised questions about whether China’s strategic alignment with a weakened Russia may turn out to be a net burden rather than a plus to China’s interests. Xi is also likely having second thoughts about his personal association with Putin and watching closely to see how the Russian leader fares in the coming weeks and months.

How has Beijing responded thus far?

Beijing has remained relatively quiet about the rapid developments inside Russia. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Rudenko traveled to Beijing on Sunday to meet with Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang and Deputy Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) simply described the meetings as exchanges on “China-Russian relations” and “international and regional issues of concern.” The MFA subsequently released a two-sentence statement describing what it termed the “Wagner Group Incident” as Russia’s “internal affair” and expressed Chinese support for “Russia in maintaining national stability and achieving development and prosperity.”

Will Beijing help shore up Putin’s grip on power?

Beijing has refrained from openly criticizing Prigozhin or expressing direct support for Putin. It will be interesting to see whether Xi breaks his silence to personally express support for Putin in the coming days or weeks, perhaps through a phone call or some other exchange. But neither the Chinese government nor Xi are likely to wade too deeply (at least publicly) into Russian political developments, for at least two reasons. First, Beijing will not want to alienate any Russian factions and potential successors to Putin in the case of the latter’s demise. And second, it will seek to publicly position China as state that doesn’t “interfere” in other’s internal politics, notwithstanding its actual track record on this claim.

While Beijing has no desire to see Putin’s downfall or Russian internal disarray, it is also unlikely to take extreme steps to help the Kremlin in ways that could directly undermine China’s own national interests, just as it has avoided major sanctions by largely refraining from providing direct lethal assistance to Russia as it battles Ukraine. If civil conflict remerges and deepens in Russia following this weekend’s episode, the Chinese government is likely to keep in close touch with the Kremlin, to insist that China-Russia ties remain unchanged and to continue trading with Moscow to the extent possible.

But China is unlikely to offer more significant forms of support, such as sending Chinese forces to assist Putin (or to imagine an egotistical leader like Putin seeking direct Chinese protection, for that matter). In the case of Putin’s imminent downfall, perhaps Beijing will – at most – offer the Russian leader the option to live in exile in China just as it took in deposed Cambodian King Norodom Sihanouk in 1970. Although again, it’s hard to imagine that Putin would want to live under Beijing’s shadow.

How might these developments impact Beijing’s position on the Ukraine war?

While Beijing has leaned in favor of Moscow over the course of the war, it has warned against nuclear escalation, expressed concern for the impact of the war on civilians and called for the cessation of hostilities. Xi could use this moment to privately nudge Putin to cut his losses and scale back his ambitions on Ukraine. Whether Putin will heed his advice is another matter, however.

What reverberations will the Russian crisis have inside China?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s worst nightmare is facing an event like the one that transpired in Russia this past weekend. The Wagner uprising has likely reinforced the CCP’s fixation on exercising absolute control and zero-tolerance for any potential challengers to its authority, whether a flamboyant party official like Bo Xilai, a Chinese “princeling” who was on track to the highest levels of leadership but is now serving life in jail for corruption; a highflying tech company or influential business leader like Jack Ma; a religious, ethnic, or student group; or even an individual whose words and actions may cast doubt on the CCP’s legitimacy and spark a movement against the central government. The CCP’s leadership will further reinforce the need for the Party to maintain absolute command over the state, the People’s Liberation Army, and all other sectors, and for Xi to be at the “core” of this apparatus.

Putin’s crisis should also give Xi greater pause in launching a military campaign against Taiwan, lest he faces similar challenges to his rule overseeing an operation that will most certainly result in the loss of Chinese lives and treasure. As such, Beijing, as well as Xi’s fervent hope, will be that Putin emerges even stronger from this weekend’s crisis – and that the Kremlin’s predicament does not set a precedent for the CCP’s own fate.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What’s at stake for China in the Wagner rebellion?

June 27, 2023