Publicly funded preschool is very popular. Nearly all Democratic presidential candidates endorse it, and 87% of voters (across political parties) support improving preschool quality and access.

Preschool’s popularity generally is well deserved. Decades of evidence show that children who attend preschool are more prepared for kindergarten than children who do not. But there have long been questions about how long the benefits of preschool last–questions that date back to the first major public investment in preschool in the United States, Head Start, in the 1960s. The overall pattern in older research is that preschool nonattenders tend to catch up to attenders in their language, literacy, and mathematics test scores in the early elementary grades (i.e., by around third grade), sometimes partially and sometimes fully. But in studies examining long-run effects, preschool participants tend to outperform nonparticipants on a wide range of behavioral, health, and educational outcomes into adulthood. Evidence from modern-day, scaled-up programs so far largely mirrors the elementary school patterns in the older studies, though a group of experts recently concluded that such evidence “is sparse, precluding broad conclusions.” Long-run evidence is not yet available for modern-day, large-scale programs.

Both older and more recent studies have given us a hint about the catch-up effect: The quality of what happens after preschool in the early elementary school years seems to matter. The preschool boost is more likely to last if children transition into early elementary schools that are higher quality and more poised to build on their stronger skills. For example, the boost from an intervention in Chicago Head Start classrooms lasted through kindergarten only if children entered higher-performing elementary schools. Similarly, the boost from Tennessee pre-K lasted only if children had access to higher-quality K-3 experiences, as defined by teacher quality ratings and schools’ contribution to improving child test scores.

As preschool programs expand nationally, understanding the catch-up effect has taken on practical importance. We need to pinpoint under what conditions the benefits of large-scale public preschool programs last so that we can design elementary schools to build on the gains in preschool.

New research from Boston

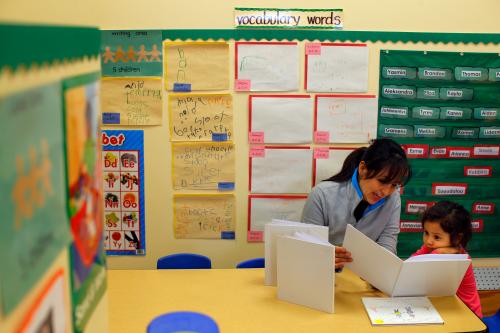

In a set of recent studies, our research team used data from the Boston Public Schools (BPS) to understand whether the boost that children get from their Boston prekindergarten program lasts through third grade, and under what conditions. Prior studies have demonstrated that the Boston program strongly boosts children’s school readiness and that the program has strong instructional quality. Importantly, Boston invested in proven curricula and coaching for teachers–the model most supported by current evidence for improving preschool quality, especially teachers’ instructional quality, at scale.

To estimate impacts of the program through third grade, we relied on lotteries for over-subscribed Boston prekindergarten sites between 2007 and 2011. In other words, for some schools, more families applied to prekindergarten than the school had space for, so seats were awarded to applicants using a lottery. These lotteries were essentially coin flips determining which students got into the most popular programs. This lottery sample comprised 25% of the children (3,182 in total) whose families applied for a seat in the program across the district. The lotteries were highly concentrated in a subset of schools–about 75% of lottery sample children competed for just a quarter of the schools with prekindergarten programs in the district. Overall, our sample was more advantaged than the full Boston prekindergarten student population. And almost all of our control group (88%) went to other preschool programs, an unusual comparison group in preschool studies. (In contrast, about 34%-50% of the comparison groups in recent preschool studies in Tulsa, Tennessee, and the national Head Start Impact Study attended other preschool programs.)

We found that our more-advantaged lottery sample did just as well in kindergarten through third grade whether they enrolled in Boston prekindergarten or not, in terms of special education placement, grade retention, and third-grade test scores. In other words, we did not see statistically significant effects of enrolling in Boston prekindergarten in later grades for the lottery sample. Underscoring that our sample was relatively advantaged, whether they attended Boston prekindergarten or not, lottery sample children scored substantially higher on third-grade standardized tests than the average BPS third grader (between 35%-53% of a standard deviation higher).

Relevant to designing elementary schools, we found that one factor does matter in whether the preschool boost lasts: the quality of the child’s elementary school. Gains from Boston prekindergarten persisted if kids applied to and won a seat in a high-quality elementary school, as defined by the school’s third-grade test scores, even when their counterparts (children who lost the lottery) enrolled in similar schools in kindergarten. Other school-quality proxies–including demand for the school, the percentage of kindergarten peers who went to the Boston prekindergarten program, and school climate–were not consistent predictors of a lasting boost.

Importantly, as is standard in this kind of study, we examined whether the lottery findings generalized to all kids who applied for/attended the program (i.e., to the 75% of appliers who did not compete in a lottery). For the full sample of children who applied to the program, enrolling in the program was associated with benefits on all outcomes we examined, with lower rates of grade retention in K-2 and special education placement in K-3, and slightly higher third-grade reading and math scores (4% of a standard deviation). But this work is correlational, and we can’t say the program caused these benefits. These analyses simply raise the issue that the lottery findings may not generalize to all students.

Implications for policy and practice

Despite the limitations of our work (e.g., a more advantaged lottery sample that may not generalize to all students), our study adds to an emerging story across the country. To realize the full potential of attending a high-quality prekindergarten program, we have to take a hard look at what happens after prekindergarten. Boston was worried enough that the prekindergarten boost wouldn’t last that it began designing and rolling out its own aligned preschool-through-second-grade curriculum in 2013. They couldn’t just purchase a curriculum shown to build on prekindergarten gains because there are no proven prekindergarten-through-third-grade curriculum models in the United States. Currently, we are conducting a large-scale study–joint across MDRC, the University of Michigan, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and BPS–that will examine whether Boston’s aligned curriculum sustains the prekindergarten boost for all students. Our results for Boston in its pre-aligned days underscore the importance of efforts to develop and test such models.

Our study also has two implications not commonly discussed in pre-K proposals. The first is that public pre-K may draw more advantaged families into urban public school systems and keep them–a potential advantage given extensive evidence on the benefits of economically integrated schools. Children who won the lottery and enrolled in Boston prekindergarten were 34 percentage points more likely to stay enrolled in BPS from kindergarten through third grade than children who lost the lottery and did not enroll in Boston prekindergarten. The second is that many disadvantaged families are not enrolling in public preschool programs. About half of entering Boston kindergarteners did not apply to the prekindergarten program as four-year-olds. Of these, about 20% attended no preschool program at all. These children were much more likely to come from low-income families and speak a non-English home language–exactly the children shown to benefit the most from public preschool programs. Nationally, enrollment rates in universal programs in the four states that offer them and in Washington, D.C., hover between 60% and 88%. As localities work toward achieving kindergarten readiness for all students, offering public pre-K is not enough. We need to find ways to help the most disadvantaged families enroll in these programs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).