In today’s political climate, trust in institutions remains deeply fractured—and nowhere is this clearer than in the competing narratives surrounding the 2020 election and the events of January 6, 2021. Yet a survey of former members of Congress offers a revealing counterpoint: Many of those who once held elected office express views on these events that diverge sharply from those of the broader public and from current political leaders.

Between June and October 2023, the UMass Poll, in partnership with the U.S. Association of Former Members of Congress (FMC), surveyed nearly 300 former lawmakers—Democrats and Republicans alike—spanning every Congress from 1963 to 2023. Though their views were shaped by different eras, institutional roles, and ideological leanings, their responses point to a shared concern about the integrity of democratic institutions and the strain of contemporary political dynamics.

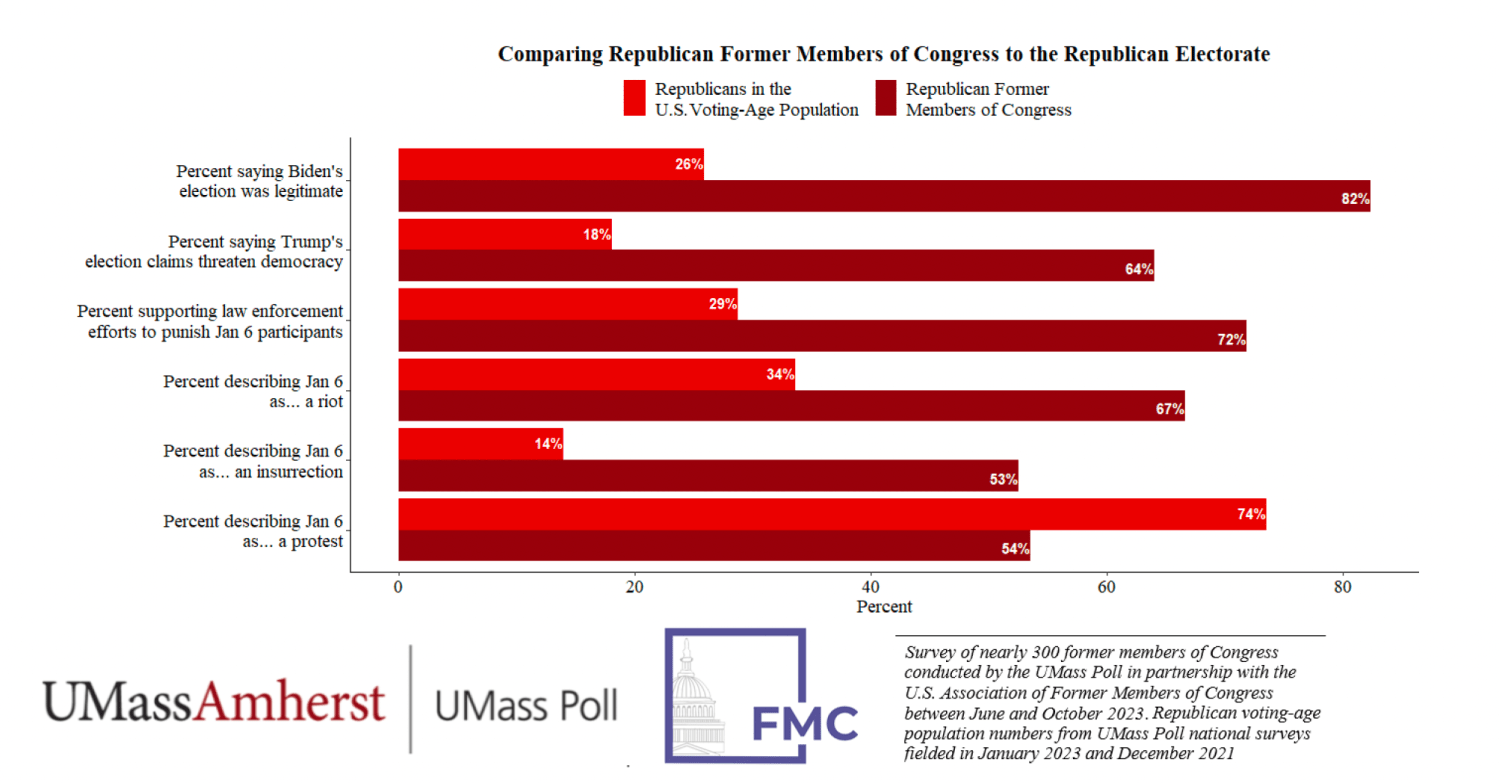

Perhaps most striking is what the survey reveals about perceptions of the 2020 presidential election. Over 80% of former Republican members of Congress said that Joe Biden’s victory was legitimate. This contrasts with roughly 25% of Republican voters who said the same in a UMass national poll. Similarly, two-thirds of former Republican lawmakers described Donald Trump’s post-election behavior as a threat to democracy—whereas fewer than 20% of Republican voters shared that view.

Figure originally appeared in the Former Members of Congress report published by FMC and UMass.

The divergence does not stop there. When asked how best to characterize the events of January 6, 2021, former lawmakers of both parties were more likely than the general public to use terms such as “riot” or “insurrection.” Former Republican members, in particular, were substantially more likely than Republican voters to adopt these terms. Likewise, more than 70% of Republican former lawmakers supported efforts to identify and prosecute individuals involved in the attack—another sharp contrast with public polling among GOP partisans.

What explains these gaps?

One possibility is that former members—liberated from the constraints of electoral politics—feel more freedom to speak candidly. Without the pressures of reelection campaigns, party primaries, donor expectations, or media scrutiny, they may be less susceptible to the reputational and political risks that shape public discourse among sitting officials. In other words, it is possible that these former members would express different opinions if they were still in Congress, and that current Republican elected officials might voice different views if not in office. Also, while most of the Republicans in this sample describe themselves as conservative, Republican former members are undoubtedly different from current members in many ways.

Another explanation lies in their institutional vantage point. Former members have seen the inner workings of Congress. Many came of age politically in eras when compromise was still possible, bipartisan norms were stronger, and institutional guardrails were more intact. Their collective experience may leave them better positioned to assess threats to the stability of American democracy—and more attuned to long-term institutional consequences. It is impossible to definitively pin the notable differences we observe on one of these potential explanations. They are certainly not mutually exclusive, and as is often the case, multiple factors can be at play simultaneously.

But the broader lesson is not just about individual opinions. It’s about the nature of democratic accountability—and the incentives shaping political behavior today. The data may suggest a misalignment between what some political elites believe and what they publicly endorse or reject. That tension—between personal conviction and political calculus—has long existed in democratic systems. Yet in today’s hyper-polarized and media-saturated environment, the costs of deviation from dominant partisan narratives have grown significantly.

The fights between the two parties have damaged institutional rules and norms that helped Congress function reasonably well. Both parties engage in what Sarah Binder calls “rule dodging,” bending or selectively ignoring established procedures to advance partisan goals. In 2013, Senate Democrats invoked the so-called nuclear option by reinterpreting Senate Rule 22 to allow cloture (ending debate) with a simple majority vote on all judicial and executive branch nominations except for the Supreme Court. In 2017, Republicans responded by applying this standard to Supreme Court nominations. In the same year, Republicans rushed floor votes to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act through reconciliation without official scoring from the Congressional Budget Office—a procedural norm designed for transparency and deliberation.

In the House, there is a similar hardball strategy to cut out the minority. Over decades, both parties have increasingly used “closed rules” to bar all minority amendments on the floor, and even block amendments in committee markups, as Speaker Pelosi did in 2019. The Democrats pared back the motion to recommit (a 100-year tradition allowing the minority to send a bill back to committee), accusing the Republicans of abusing the House rule simply to embarrass the majority party for a vote intended to carry symbolic punch rather than modify the bill. The list goes on with highly partisan select committees setting up lopsided structures, denying minority appointees, for example, with the Benghazi Committee (2014) and the January 6 Committee (2021).

These practices undermine the very idea of collective self-governance under bipartisan rules and diminish Congress as a deliberative body that engages with the minority party. Similarly, party polarization under unified government weakens congressional oversight of the executive branch. This pattern aligns closely with the concerns expressed by former lawmakers in this survey about maintaining institutional prerogatives notwithstanding partisan loyalties. Ultimately, the tit-for-tat hardball tactics we describe incur costs of institutional capital and public legitimacy when the body is viewed as hyper-partisan.

Outside the arena, a different view of American democracy

It is important not to romanticize the past. Former members are not immune to political calculation or hindsight bias. But their collective voice in this survey adds depth to our understanding of elite opinion and raises questions about the structural conditions that shape public leadership. Why do these views become more visible only after officials leave office? And what might it take to create conditions in which political leaders feel more empowered to speak forthrightly while still serving?

There are no easy answers, but the findings suggest some potential avenues for reform. Institutional changes—such as redistricting to reduce the prevalence of safe seats, increasing turnout in primaries to broaden the electorates beyond the most intense partisans, or revisiting rules that structure the legislative process—may help recalibrate some incentives. So too could shifts in political culture that might reward institutional loyalty and elevate cross-partisan respect. To be sure, these are challenging goals with no guarantee of success.

The survey also included a range of other topics that point to shared concerns. A majority of former members, across party lines, expressed pessimism about the current state of Congress and U.S. democracy more broadly. “Dysfunctional,” “divided,” and “polarized” were among the most frequent descriptors. Over 80% believe that Congress has lost power relative to the executive branch, and 65% believe it has lost ground to the judiciary. At the same time, most respondents reported still socializing across party lines and said they would run for public office again if starting their careers today—a reminder that political polarization is not always personal.

These findings paint a picture of an institution under stress but not beyond repair. Former lawmakers bring valuable insights into how political life has changed—and what might be done to revitalize it. They offer a kind of democratic memory: a living archive of institutional knowledge and civic norms that are often obscured in the heat of present-day conflicts.

In a moment when public trust in government remains low, listening to those who once governed—especially when their views cut against prevailing political winds—can offer a clearer view of where American democracy stands, and what might be needed to strengthen it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What former lawmakers reveal about the strain on American democracy

September 24, 2025