When the 117th Congress convened on Jan. 3, 2021, President Donald Trump—who, along with other members of his administration, had been the subject of significant fact-finding efforts by the House of Representatives over the previous two years—had just weeks left in his term. Before he left office, however, the U.S. Capitol saw its worst acts of violence since the War of 1812 during the insurrection that disrupted the counting of the Electoral College votes on Jan. 6. The House of Representatives responded by impeaching him for his role in inciting the attack on Jan. 13, marking the first time a president was impeached twice.

Much of the focus of congressional oversight activity in the early weeks and months of the 117th Congress, then, continued to focus on the now former president. Indeed, as we demonstrate below, January 6th remained a major emphasis of oversight efforts throughout 2021 and 2022.

But the transition of power at the start of 2021 from divided to unified party control in Washington stood to matter for congressional oversight of the executive branch for reasons beyond the emergence of a new, historically important event meriting significant congressional attention. One of the major findings of previous work on congressional oversight is that partisan dynamics matter. Work on congressional inquiries between 1898 and 2014 finds that when the president is of one party and the House majority is of the other, committees investigated the executive branch more aggressively.1 Other research on investigations of “executive misbehavior” similarly concludes that they are more likely under divided government.2 Interviews with individuals involved in the contemporary oversight process also reflect this pattern of more aggressive inquiry when Congress and the White House are controlled by different parties; as a staffer on the Senate Judiciary Committee described it, “‘you’re going to have more oversight hearings…if the opposing party is in the White House and it’s going to be on a different set of subjects.’”3

Other work demonstrates how these partisan dynamics interact with the resource capacity of congressional committees—especially in terms of staff levels. Oversight, whether it is in the form of hearings, letters, or other work, does not happen on its own; it requires resources and expertise. Committees that lack this capacity are unable to oversee the executive branch effectively, even when they might be motivated to do so by partisan concerns. While, on the whole, a chamber that is controlled by the opposite party from the president does more hearings on average, this effect of divided government gets washed out when a committee has low staffing levels.4

Much has been made of the idea that oversight, especially in the form of hearings, has become increasingly focused on creating “gotcha” moments for the individuals involved.5 Evidence does suggest that members who are more extreme ideologically are more likely to engage in oversight,6 and that members today are more likely to criticize a president of the opposite party during hearings than in the past.7 But confrontational hearings can play an important role in framing issues and garnering attention to them,8 and attract higher attendance on the part of members.9

More generally, as control over the legislative agenda in Congress has been centralized in the hands of party leaders, committees have responded by exercising more of their policy influence through oversight. The number of non-legislative hearings held by committees, for example, has remained relatively constant since the 1980s, but these sessions represent an increasing share of committee activity; committees, in other words, appear to be re-allocating their energy to tasks that are more likely to pay policy dividends. Importantly, these non-legislative activities can be beneficial to committees and their members, as they give legislators a chance to devote attention and effort that are related to whatever their personal goals for congressional service are.10

This existing research motivates several different questions about oversight in the contemporary Congress. With a party switch in the White House between the 116th and 117th Congresses, did we see a shift in how the House—controlled by Democrats throughout—examined activities by the executive branch? Do we see the influence of party priorities carrying over into oversight choices from the agendas set for consideration of bills? How does the Senate’s responsibility for advice and consent of nominations affect the amount of effort its committees exert on oversight? Below, we explore these and other topics using four years of data on oversight activity in the House of Representatives along with two years of data on analogous efforts in the Senate.

To track whether and how the House Democratic majority exercised oversight authority over the Trump administration, we launched the Brookings House Oversight Tracker in 2019 using two indicators of oversight activity: hearings held by House committees and subcommittees, and publicly released letters sent by those panels.11 We collected information on every hearing and on every publicly available letter, including the topic and the committee or committees involved; for letters, we recorded the recipient or recipients, and for hearings, we noted the witnesses and their affiliations. Using this information, we then categorized each letter or hearing along two dimensions. First, did the letter or hearing constitute an effort to oversee the activities of the executive branch? And second, what was the primary policy focus of the letter or hearing? (For more details on how we collected and coded information, please see the Appendix.)

In assigning congressional activity to these categories, we drew extensively on prior research on both oversight and policy dynamics in Congress. In the case of the former, we devised a two-tiered “keyword and key witness” approach to determining what was and was not oversight.12 In addition, we required that the target of the inquiry be the federal government, rather than a state government, a private company, or other actor.13

To classify oversight activity by policy area, we utilized a coding scheme developed by the Policy Agendas Project.14 Because the Project applies these same issue codes to other content—such as presidential speeches, media content, and party platforms—we can compare the amount of attention paid to a given issue via executive branch oversight to the focus placed on it via other means. To make our analysis most useful for non-academic audiences, we chose to collapse the Policy Agendas Project’s topic areas into 10 general policy areas.15

When Democrats took control of the Senate after the 2020 elections, we expanded our data collection efforts to include the upper chamber, using a similar data gathering approach. Collecting information on the Senate allows us to explore questions about whether two chambers in which the same party holds a majority approach oversight of an executive branch also controlled by their party similarly or differently.

Oversight in the 117th Congress

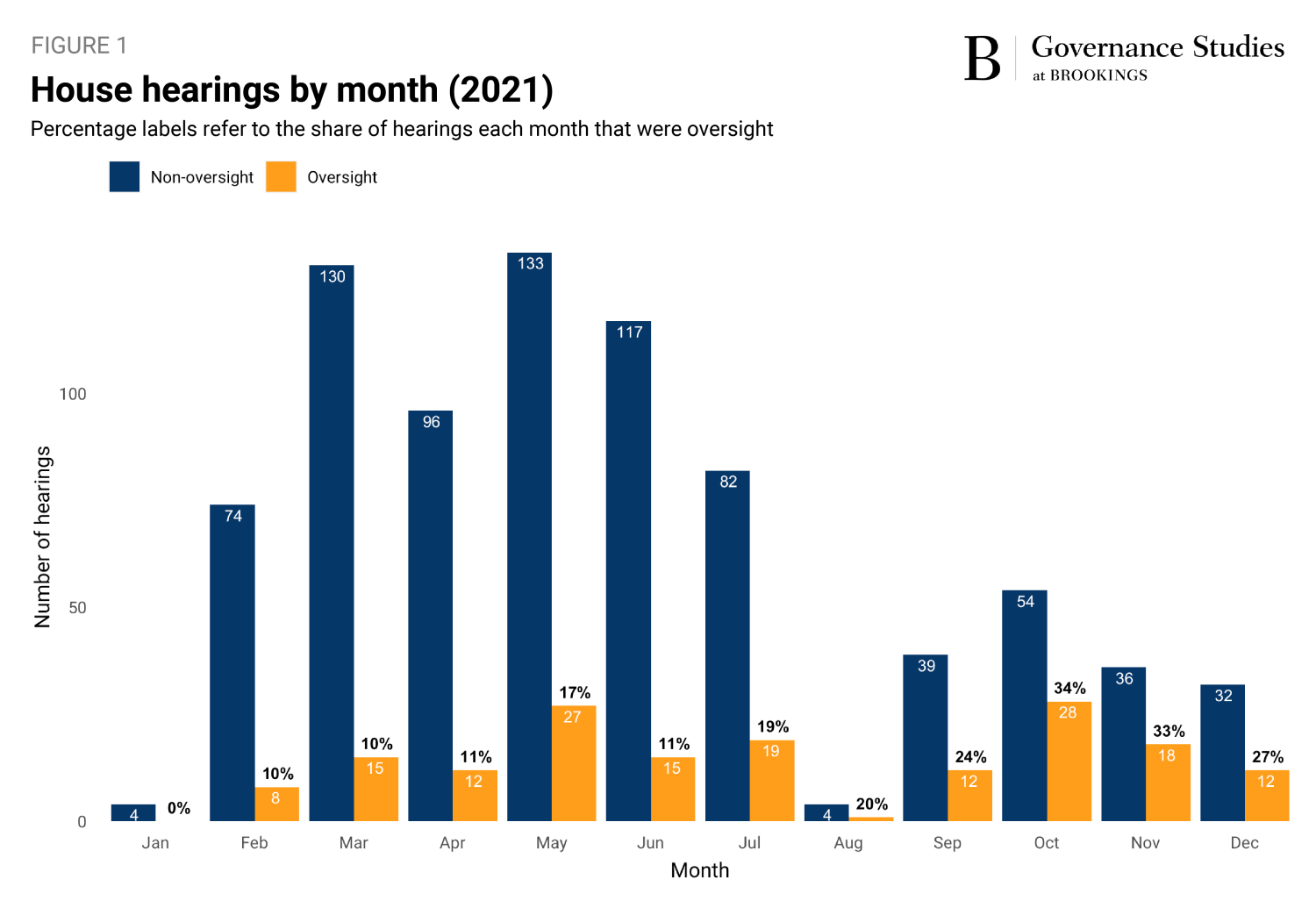

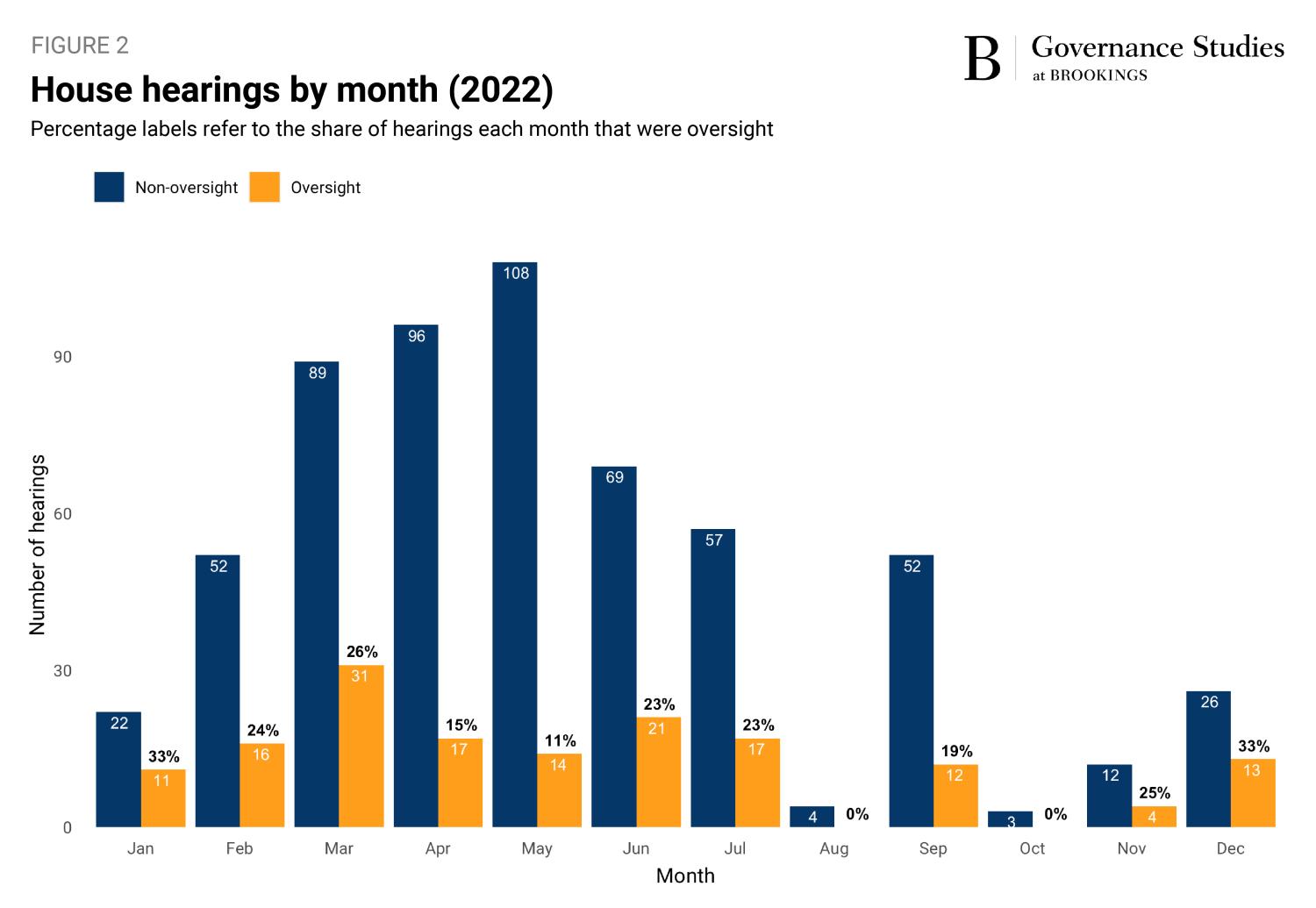

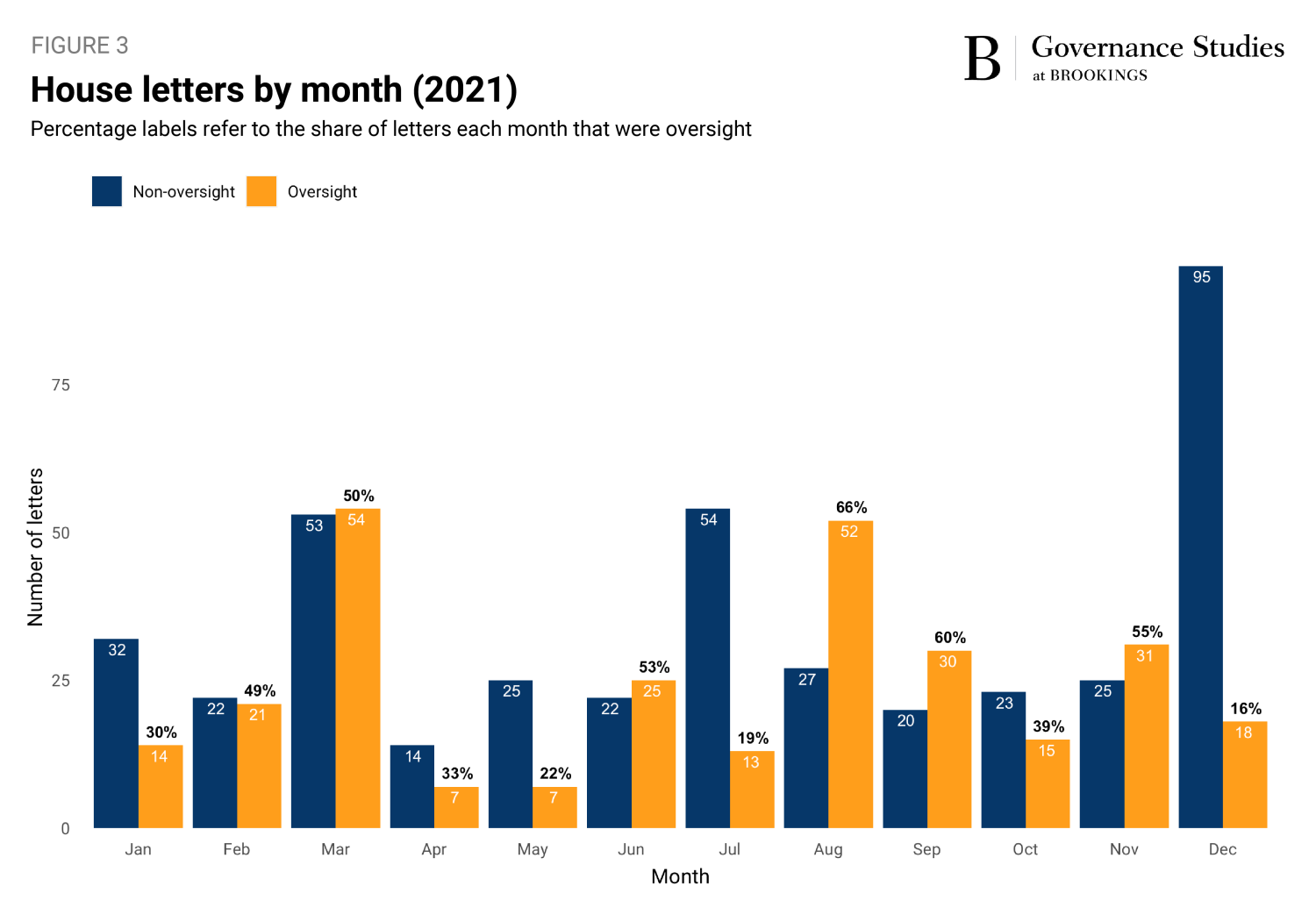

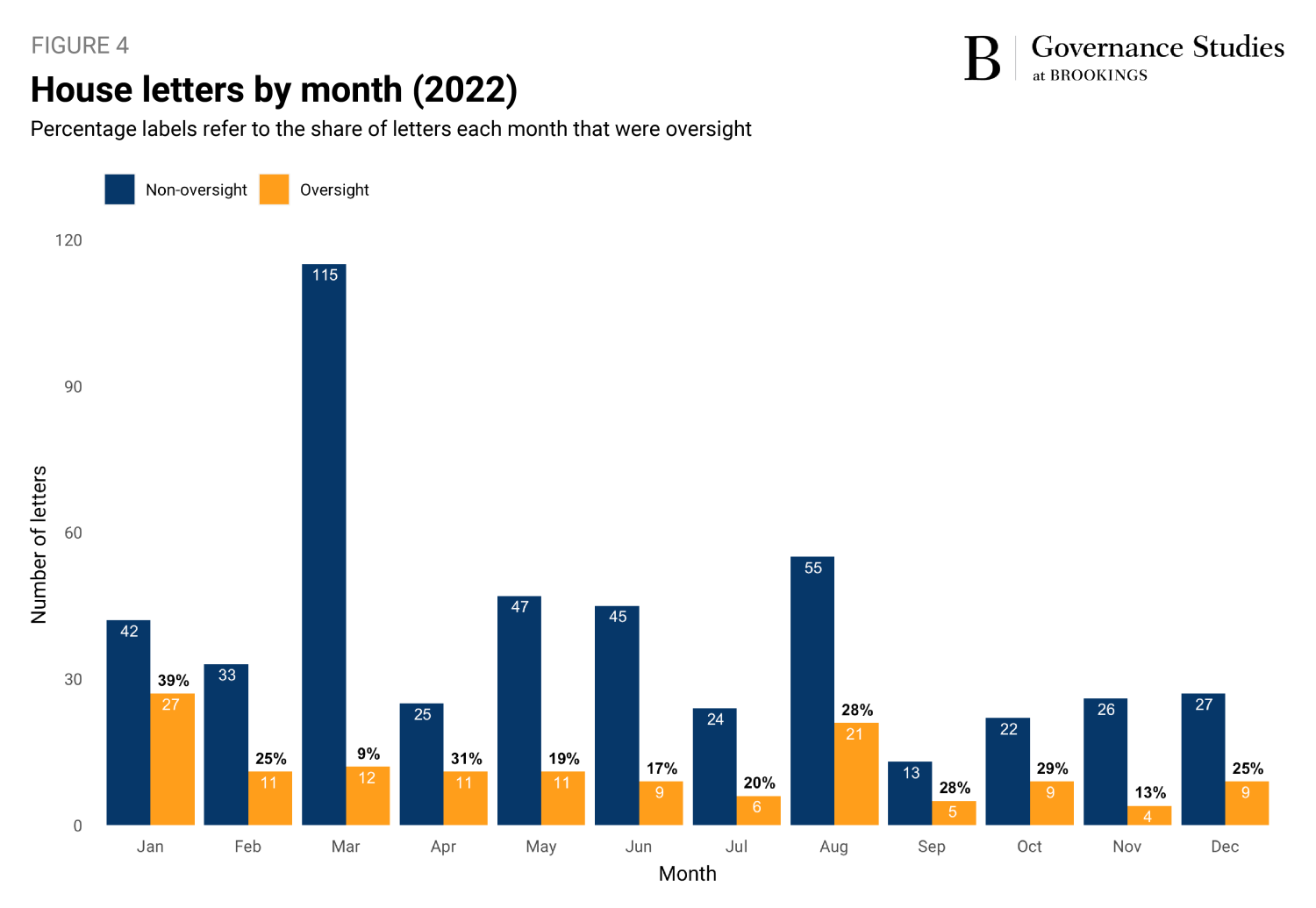

We begin our examination of oversight activity in the 117th Congress by examining how committees allocated their time across executive branch oversight versus other tasks (such as legislative hearings and non-executive branch oversight), in both the House and the Senate. The blue bars depict non-oversight activities, while the orange bars represent oversight hearings and letters.

In the 117th Congress, 19% of House hearings involved oversight of the executive branch. The first half of 2021 began relatively slowly, with only 10% of hearings per month on average being oversight. This slow start may be in part because the 117th Congress marked Democrats’ first trifecta (unified control of all of the House of Representatives, Senate, and presidency) since the 111th Congress, and attention was shifted towards legislating away from executive oversight. The pace began to pick up in July 2021, and the share of hearings that were executive branch oversight continued to remain high through the end of the 117th Congress, only dipping below 20% in six out of the 18 months. Three months in the 117th Congress saw no executive branch oversight hearings—January 2021, August 2022, and October 2022. The lack of oversight hearings in January 2021 again may be explained by the presence of other priorities in the earliest weeks of a congressional session, and in both August and October 2022 the House was on a month-long recess.

In comparison, 32% of letters sent by House committees in the 117th Congress involved executive branch oversight. The share of letters sent by committees that concerned oversight of the executive branch remained relatively high throughout the first session, only dipping below 30% in three months of the year (May, July, and December). At its peak in August 2021, the share of letters that involved executive branch oversight was 66%. In the second session, there was a notable decline in the share of letters that concerned executive branch oversight, with only two months of the year (January and April) seeing more than 30% of their letters involving executive branch oversight.

Notably, almost 70% of all House oversight letters from the 117th Congress were sent during the first session, and of these, over 30% alone were from the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, hereafter referred to as the January 6th Committee. Even more notably, the January 6th Committee sent out its first publicly available letters on Aug. 25, 2021, over halfway through the first session, highlighting just how intense their oversight activity was in a short period of time. Due in part to this activity from the January 6th Committee, House committees as a whole allocated a substantially larger share of their letters (41%) to executive branch oversight than hearings (17%) in the first session. In the second session, however, attention to executive branch oversight was more similar across the two tactics (22% of letters and 21% of hearings).

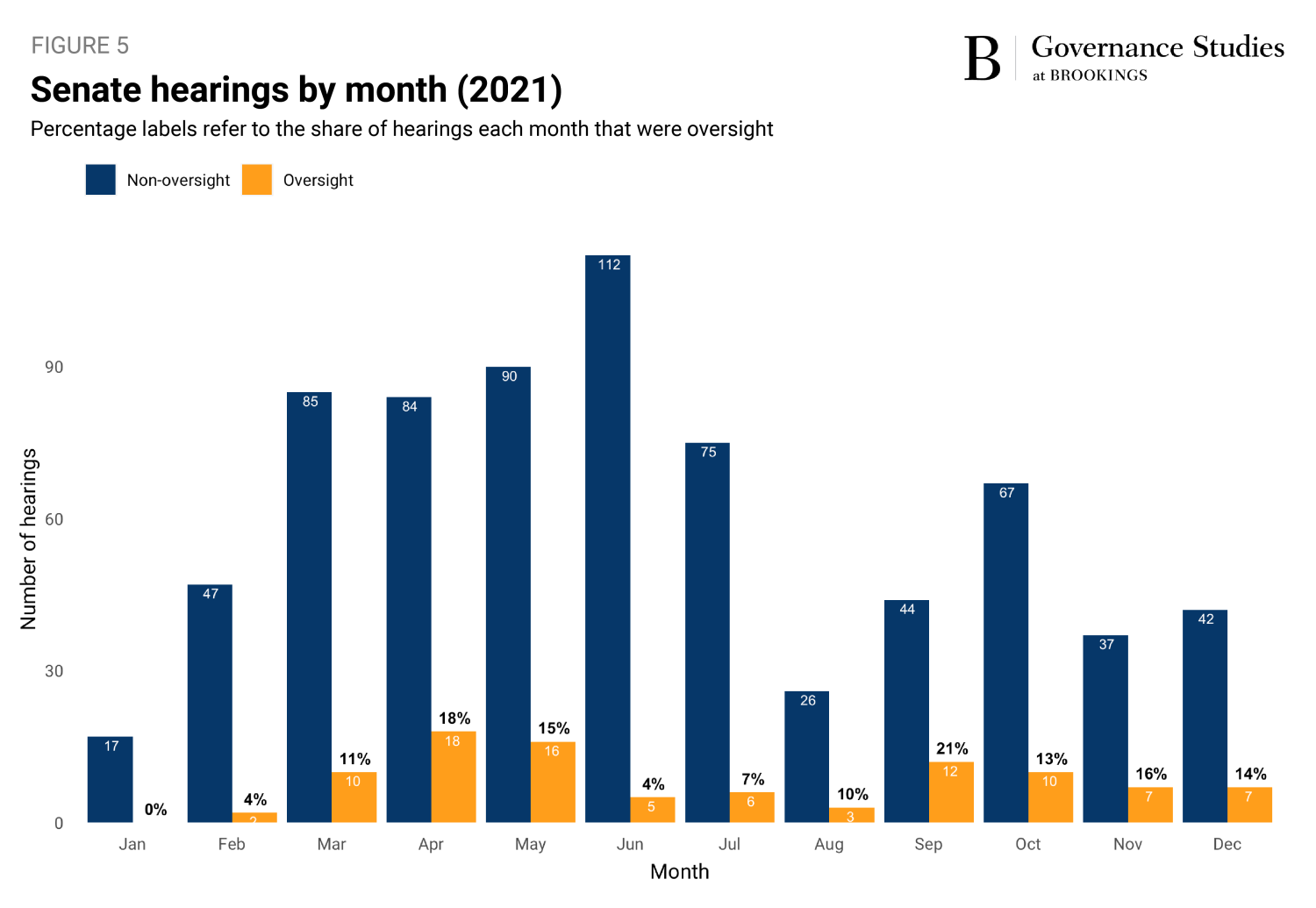

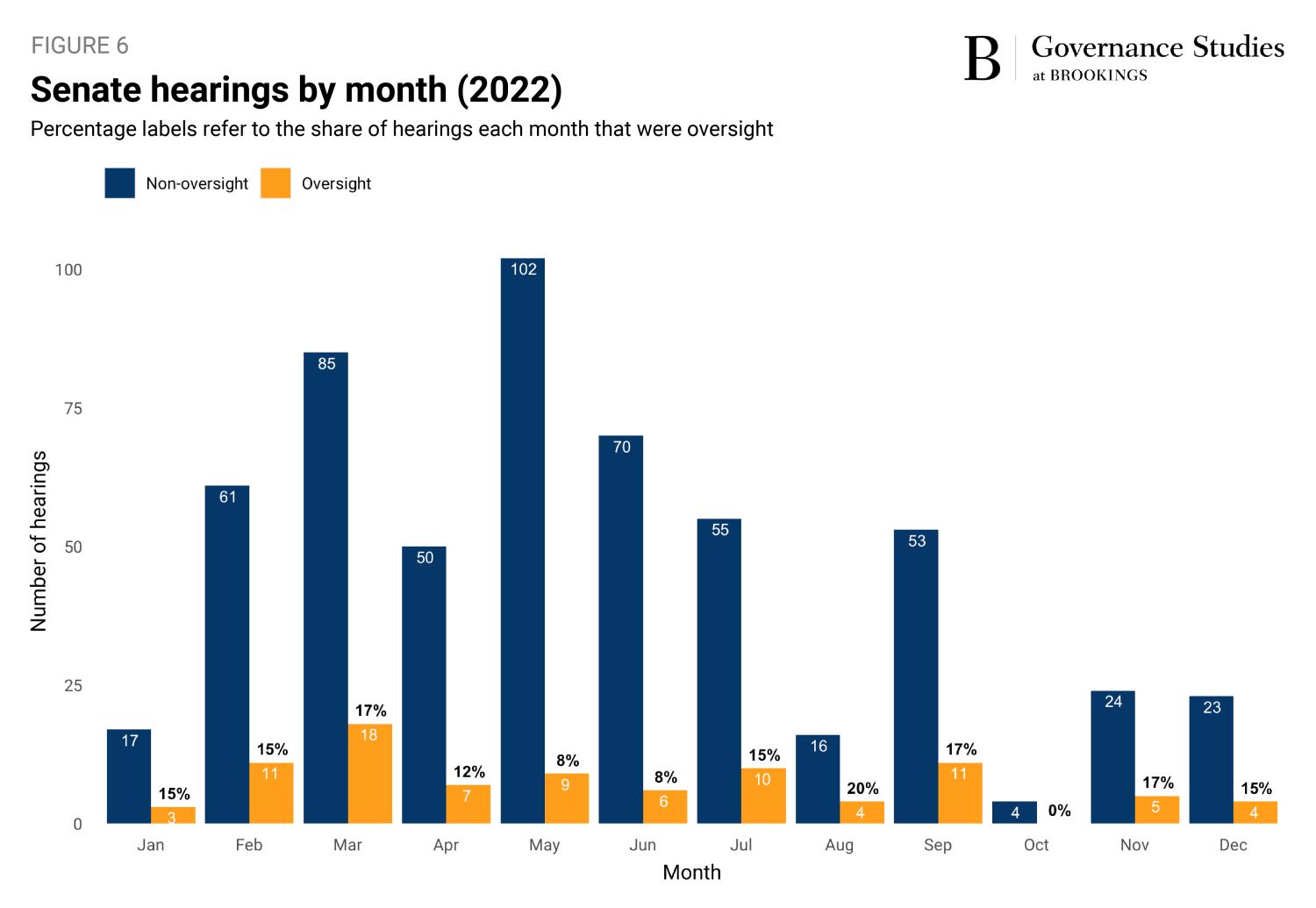

On the Senate side, 13% of hearings during the 117th Congress constituted oversight of the executive branch. Similar to the House, the first six months of the first session had the lowest average share of oversight hearings, followed by a higher, more consistent rate for the remainder of the Congress. Overall, the difference between the two sessions was slight (12% of hearings in 2021 involved executive branch oversight, as compared to 14% in 2022). In two months of the 117th Congress (January 2021 and October 2022), the Senate conducted no executive branch oversight hearings.

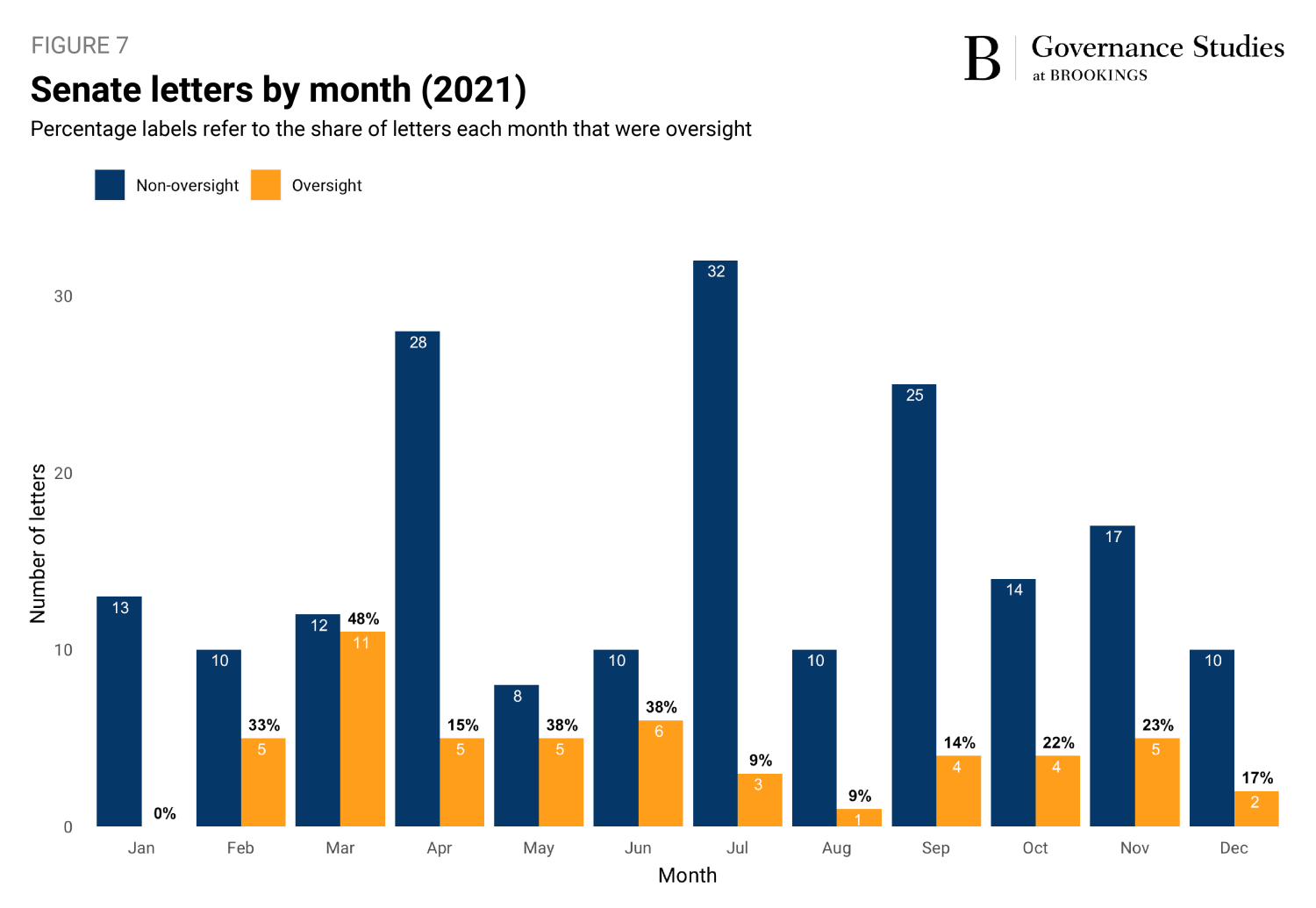

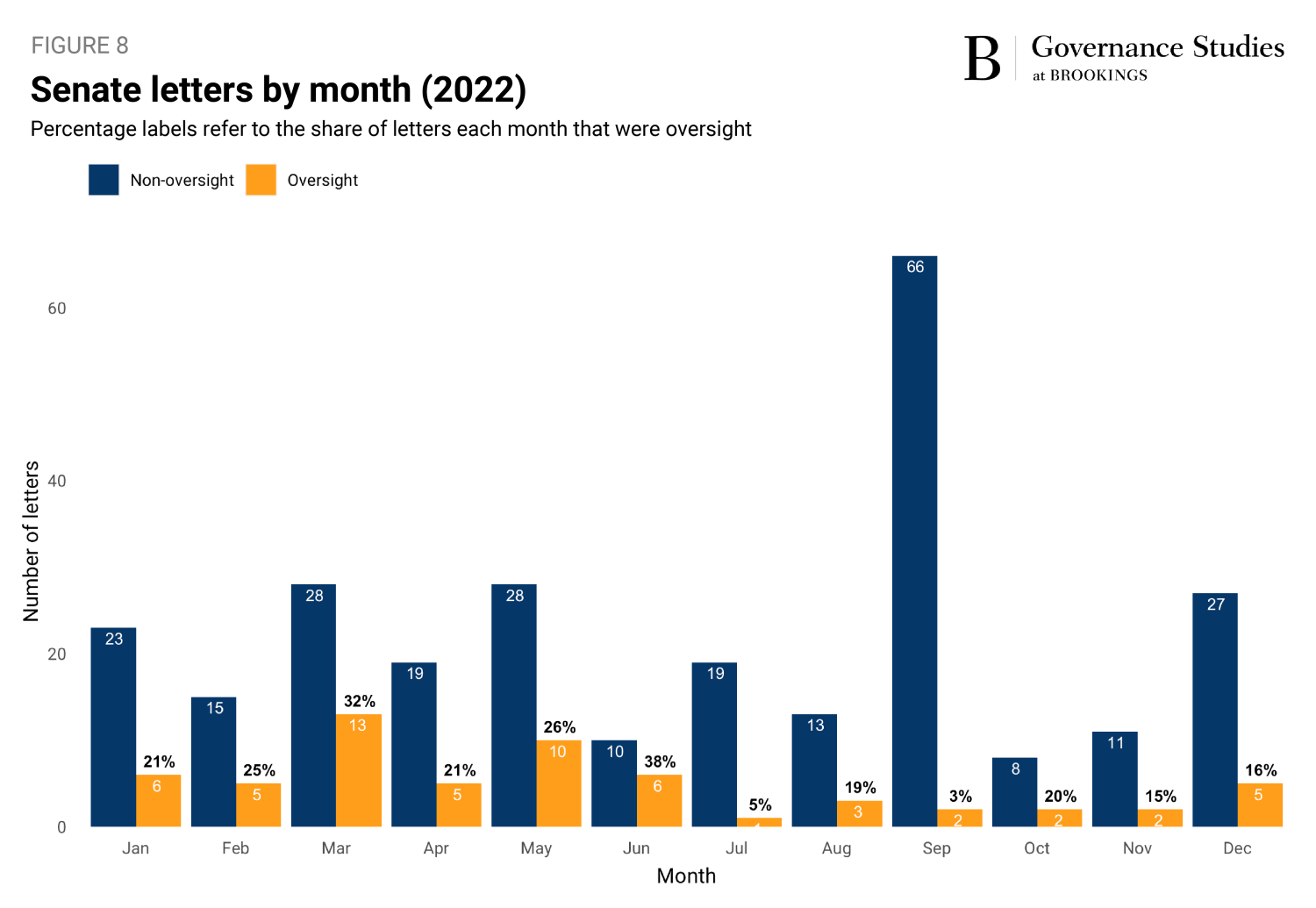

Of the letters sent by Senate committees in the 117th Congress, 20% constituted oversight of the executive branch. For both sessions of the 117th Congress, the first half of the session saw a higher average share of letters involve executive branch oversight than the second half, with the first six months of 2021 being the single highest period. Furthermore, the average share of letters that were oversight remained relatively stable between the two sessions—22% in the first session and 20% in the second.

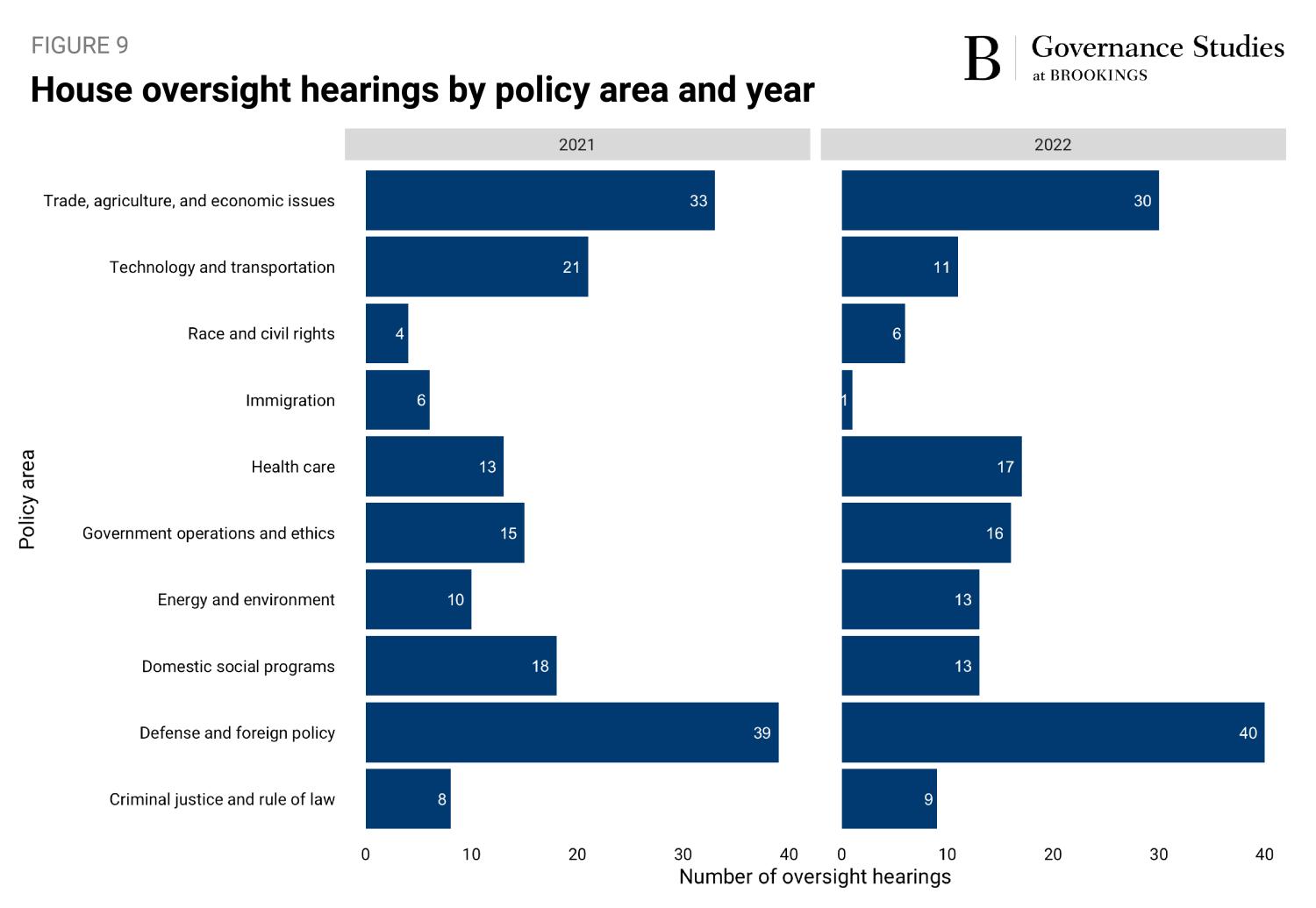

In addition to examining the allocation of committee attention to oversight of the executive branch as compared to other tasks, we also investigate the policy areas on which committees in both chambers tended to focus. For both sessions of the 117th Congress, the topic with the largest share of House oversight hearings was Defense and Foreign Policy. This level of attention was stable across the two sessions, with 39 hearings in the first and 40 held in the second. The second-most prevalent area was Trade, Agriculture, and Economics, which saw similarly consistent consideration across the two sessions (33 hearings in 2021 and 30 in 2022). At the other end of the spectrum, the topics on which House committees focused the least were also similar across the two sessions, with Immigration (six in the first, one in the second session), and Race and Civil Rights (four in the first, and six in the second session) being the least frequently examined policy areas. This shows that the issues the House focused on in its hearings remained very constant throughout the 117th Congress.

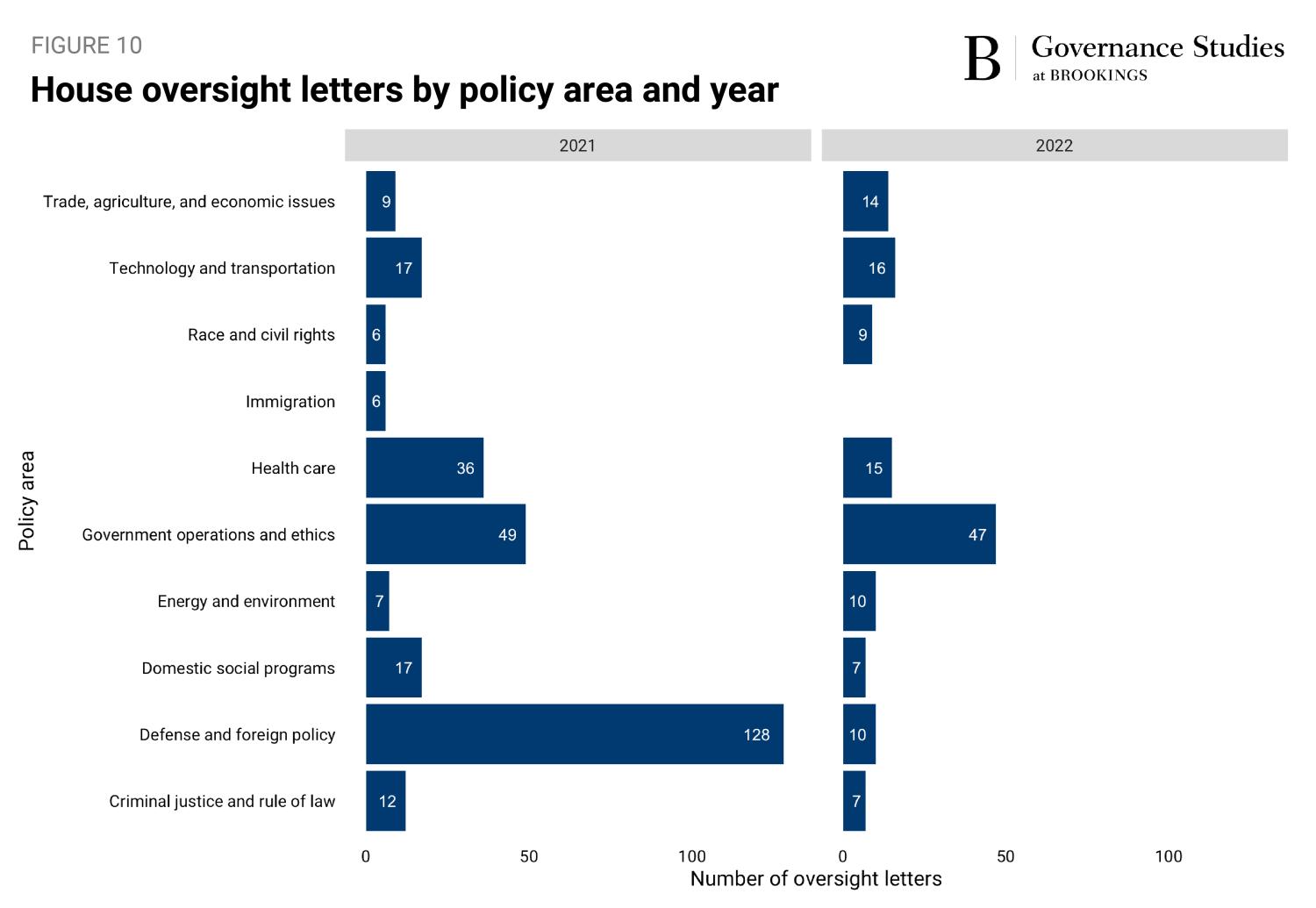

In the context of letters, Defense and Foreign Policy overwhelmingly had the most executive branch oversight letters sent in the first session of the 117th Congress, with 128 oversight letters—more than double the next-highest topic of Government Operations and Ethics, which had 49 letters. This may have been driven in part by activity from the January 6th Committee, which sent 82 letters placed in this category in the first session alone. (Our approach to classifying oversight activity by policy area puts that investigation under the heading of general domestic terrorism prevention efforts, which falls under national defense.) Leading up to its very publicized hearings presenting its findings on the events surrounding the attack, the committee sent many letters seeking information about the role of former executive branch officials and President Trump in advance of the insurrection as well as their conduct on the day itself. In 2022, Government Operations and Ethics was the most prevalent topic for oversight letters, with 47. Defense and Foreign Policy dropped significantly in this session, falling to only 10 oversight letters. The topic with the lowest number of oversight letters in both sessions was Immigration, with only six letters in the first and no letters in the second session.

For both sessions of the 117th Congress, the topic with the largest share of House oversight hearings was Defense and Foreign Policy. This level of attention was stable across the two sessions, with 39 hearings in the first and 40 held in the second.

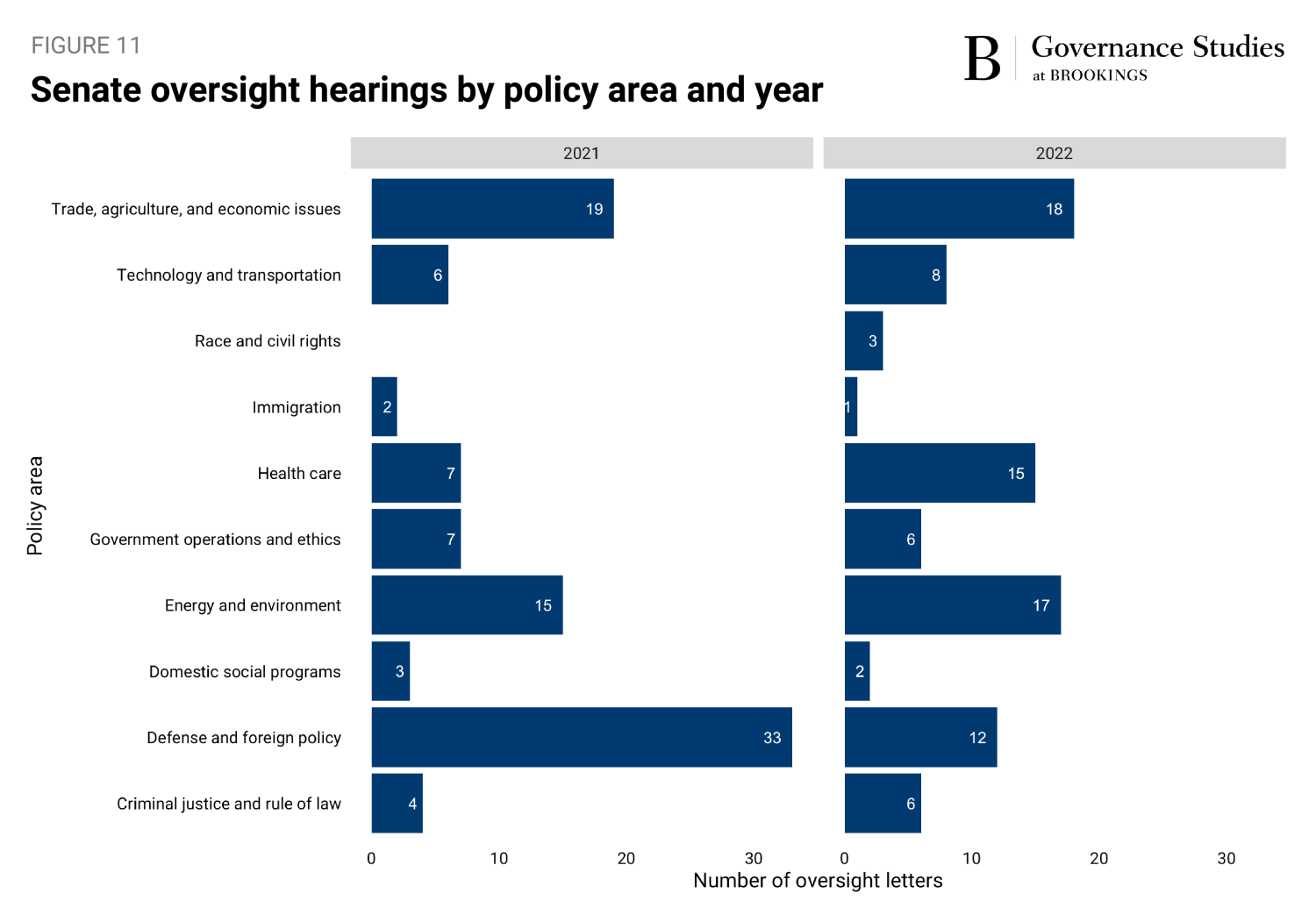

For the Senate, the policy breakdown of executive branch oversight hearings in 2021 closely reflects what we see in the House. The two topics with the most hearings during this period were Defense and Foreign Policy (33) and Trade, Agriculture, and Economic Issues (19), and two with the lowest number of hearings were Immigration (two) and Race and Civil Rights (zero). Attention shifted in the second session, where the two most prevalent topics are Trade, Agriculture, and Economic Issues with 18 hearings, and then Energy and Environment as a close second with 17. Defense and Foreign Policy remained one of the top policy issues, with 12 hearings held during this period. As for the topics on which few hearings were held, Immigration saw only one hearing held during this period while Domestic Social Programs saw two.

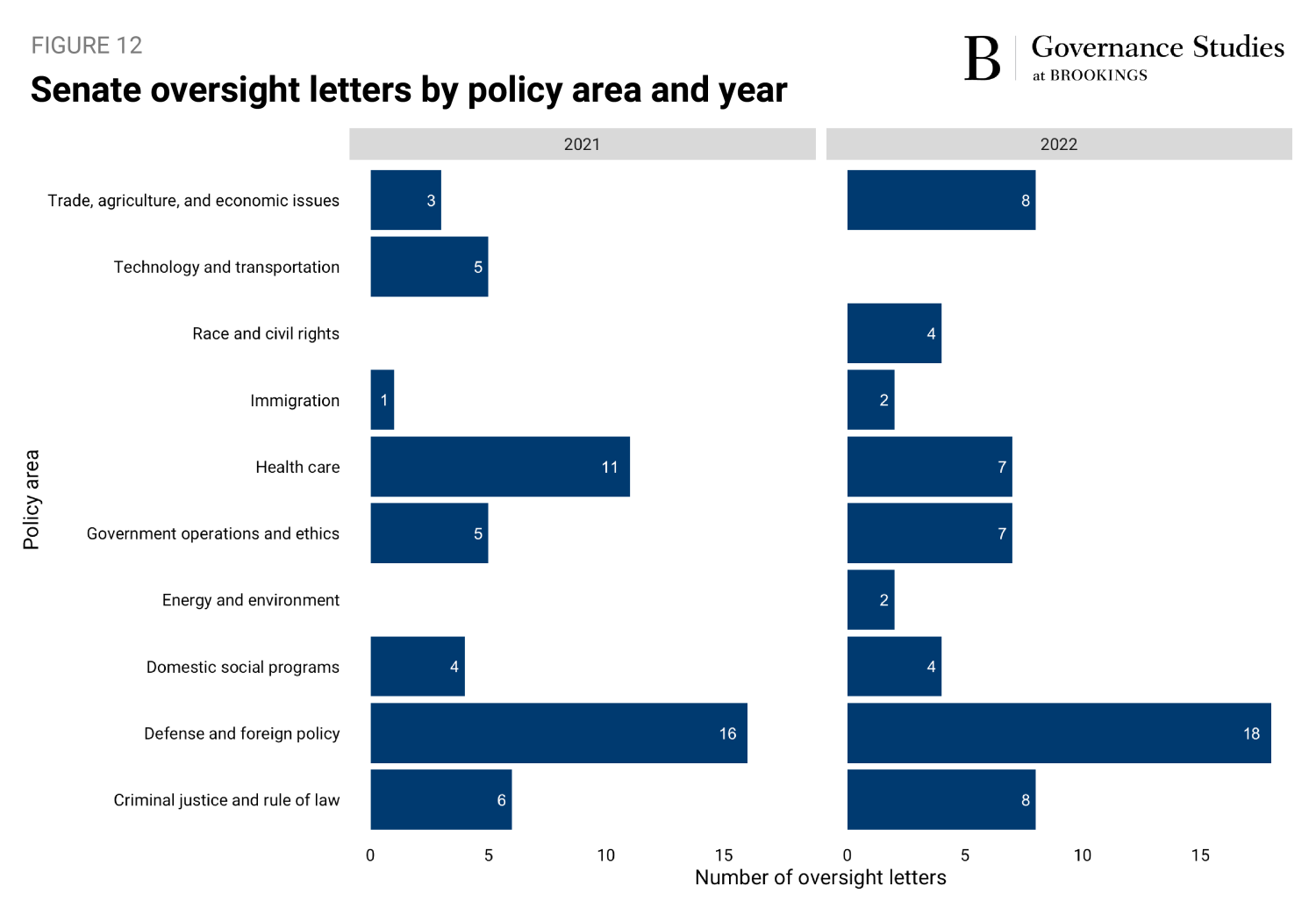

When we examine letters, we see a more significant difference between the House and Senate. While Defense and Foreign Policy was the most commonly addressed topic in the Senate in both 2021 (16 letters) and 2022 (18 letters), there was a broader diversity of policy areas that received roughly equivalent levels of attention. In the first session, the second most frequent topic was Health Care (11 letters), followed by lower but similar attention to Criminal Justice and the Rule of Law; Government Operations and Ethics; and Technology and Transportation. In the second session, meanwhile, Criminal Justice and the Rule of Law; Trade, Agriculture, and Economic Issues; Government Operations and Ethics; and Health Care were the focus of comparable levels of interest.

As outlined above, previous research suggests that we should see less oversight of the executive branch when the House of Representatives and the White House are controlled by the same party. Beyond potential alignment on issue priorities and a desire to avoid embarrassing a president of one’s own party, shifts in party control also mean changes in the committee leadership. New chairs are likely to have particular interests and relationships with groups that will shape their oversight agendas.16

Comparing the levels of oversight activity across the 116th Congress, with Democrats holding a majority in the House and a Republican in the White House, and the 117th, when both were controlled by Democrats, supports the expectation that we will see changes in oversight behavior with shifts in party control—especially in the context of letters.

In the 117th Congress, House committees held about 20% fewer hearings focused on oversight of the executive branch than in the 116th Congress (323 as compared to 405). Because the overall number of hearings held by House committees declined slightly across the two periods (by roughly 7%), the change in the share of attention committees paid to oversight via hearings was not as dramatic; 22% of hearings in 2019 and 2020 focused on executive branch oversight as compared to 19% in 2021 and 2022. If we examine the share of committee hearings that involved executive branch oversight by year, we see that the first year of the 117th Congress, 2021, saw the least attention devoted to oversight efforts, at 17% of hearings. In the other three years—2019, 2020, and 2022—the share was higher (21%, 23%, and 21% respectively). Given the dynamics of the legislative process, this is unsurprising; the first year of a new Congress under unified party control might reasonably be expected to be the period when a focus on legislation, rather than oversight, is likely to bear the most fruit.

The change in the use of letters as a tool of executive branch oversight is more dramatic. In the 116th Congress, under divided government, House committees sent roughly three times as many letters aimed at overseeing the executive branch than in the 117th Congress. Importantly, as documented in our report on oversight in the 116th Congress, the number of letters sent in the 116th Congress may have been exceptionally high, as committees shifted their attention away from hearings and to letters when the COVID-19 pandemic prevented them from gathering in person safely in 2020.17 Even considering this explanation, we still see evidence of a shift in attention under unified party control, as committees devoted 32% of their 2021 and 2022 letters to executive branch oversight versus 63% of their 2019 and 2020 letters.

Examining the levels of executive branch oversight on various issues across the two congresses gives a fuller picture on how committees’ behavior changed between a period of divided party control and one of unified party control. In all but one of the 10 policy areas we examine, there were fewer combined oversight activities in the 117th Congress than in the 116th; the only exception was Defense and Foreign Policy, which, as explained above, includes the efforts to investigate the domestic terrorism involved in the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Indeed, the relative importance placed on different policy areas across the two congresses is consistent with changes in Democrats’ oversight agenda with President Trump in the White House as compared to President Biden. In some cases, there were similarities. In both congresses, for example, a relatively large share (25% in 2019 and 2020, and 17% in 2021 and 2022) of executive branch oversight involved Government Operations and Ethics; regardless of whether the White House is controlled by the same party as the House, we would expect basic agency operations and potential ethical lapses to be a focus on oversight efforts. In contrast, in the 116th Congress, roughly 10% of committee executive branch oversight activity involved Criminal Justice and the Rule of Law, which included the efforts to oversee the Mueller investigation and other investigations into the conduct of various officials in the Trump administration. In the 117th Congress, by comparison, only 5% of oversight activity fell in that category.

In both congresses, for example, a relatively large share (25% in 2019 and 2020, and 17% in 2021 and 2022) of executive branch oversight involved Government Operations and Ethics; regardless of whether the White House is controlled by the same party as the House, we would expect basic agency operations and potential ethical lapses to be a focus on oversight efforts.

Beyond issues, we might also expect to see differences in the share of witnesses in executive branch oversight hearings that come from federal agencies depending on whether the same party controls the White House and the House. Previous research suggests that Congress may be less interested in policy learning under divided government; in contrast, under unified party control, when legislators from the majority party have a greater likelihood of enacting their policy priorities, they may seek out bureaucratic witnesses who can help them craft optimal legislative solutions. As a result, this work suggests that we should see fewer bureaucratic witnesses when the president and the House majority are controlled by opposite parties.18

Beyond this general trend, we also saw several high-profile instances of executive branch officials refusing to appear before House committees in 2019 and 2020. Overall, then, we might expect that divided government would see fewer agency witnesses for reasons related to witness cooperation as well as because of the interests of committees. Indeed, when we compare the share of witnesses at executive branch oversight hearings in the House in the 116th and 117th Congress, we see that, despite engaging in more oversight of the executive branch, a smaller share of the witnesses at those hearings actually came from agencies. In 2019 and 2020, 43% of all witnesses at executive branch oversight hearings were from federal agencies. In 2021 and 2022, that figure rose to 51%. While committees may do less oversight of agencies under unified party control, that oversight appears to feature more witnesses from agencies themselves.

In our report on executive branch activity in the 116th Congress, we discussed at length the degree to which the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic shaped investigative behavior in 2020. Notably, when committees were more limited in their ability to gather in person, we saw the House transfer its oversight energy from hearings to letters; House committees held 45% fewer oversight hearings in 2020 than in 2019 but sent 44% more oversight letters. In addition, when we compare the issues on which the House conducted the most executive branch oversight across the two sessions of the 116th Congress, we see more emphasis on health care issues in 2020 than in 2019—just as one would expect in response to a once-in-a-generation global pandemic.19

The COVID-19 pandemic—both as a public health crisis that affected the ability of congressional committees to do the in-person components of their work and as an extraordinarily pressing policy question—is an especially stark example of the way in which congressional choices about how and on what issues to conduct executive branch oversight are not made in a vacuum. The decisions about what to oversee, and how to do so, are part of a broader ecosystem of committees’ work.

Each chamber can and does make choices about the level of financial resources to allocate to committees, implementing, at various points, both cuts and increases.20 But perhaps the scarcest resource available to committees is time, and committees face choices about how to allocate their effort across the various activities they could pursue. In the contemporary era of increasing amounts of legislative power being held centrally in the hands of party leaders, we see committees choose to allocate more of their hearings to oversight than to legislating, believing that their time is better spent on activities over which they have more control as opposed to work, like bill writing, that might get ignored or disregarded by party leaders.21 Other research suggests that, more generally, Congress demands more expert information when issues become salient to the public.22

What insights can our data on executive branch oversight shed on these questions about prioritization—both of executive branch oversight in comparison to other functions and of oversight across various issues? On the former, the period covered by our analysis of oversight in the Senate is especially ripe for an exploration of how Senate committees prioritize their nominations responsibilities versus their oversight ones for several reasons. First, the initial two years of a new presidential administration are ones in which we would expect committees to prioritize processing executive branch nominations. Second, the 117th Congress was only the second such period at the start of a new presidential administration where the Senate could invoke cloture on all nominations to the executive branch and all levels of the federal judiciary with only a simple majority, rather than three-fifths. (Thanks to change in the Senate’s precedents in 2013, this was also possible for all nominations below the Supreme Court at the start of the Trump administration in 2017.) Finally, the Democrats’ exceedingly narrow majority in the Senate in 2021 and 2022—when the chamber was split 50-50, with Democrats asserting a majority via the tie-breaking vote of the vice president—further incentivized a focus on nominations at the simple majority threshold, as most legislating still required cooperation with Republicans to reach the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture.23

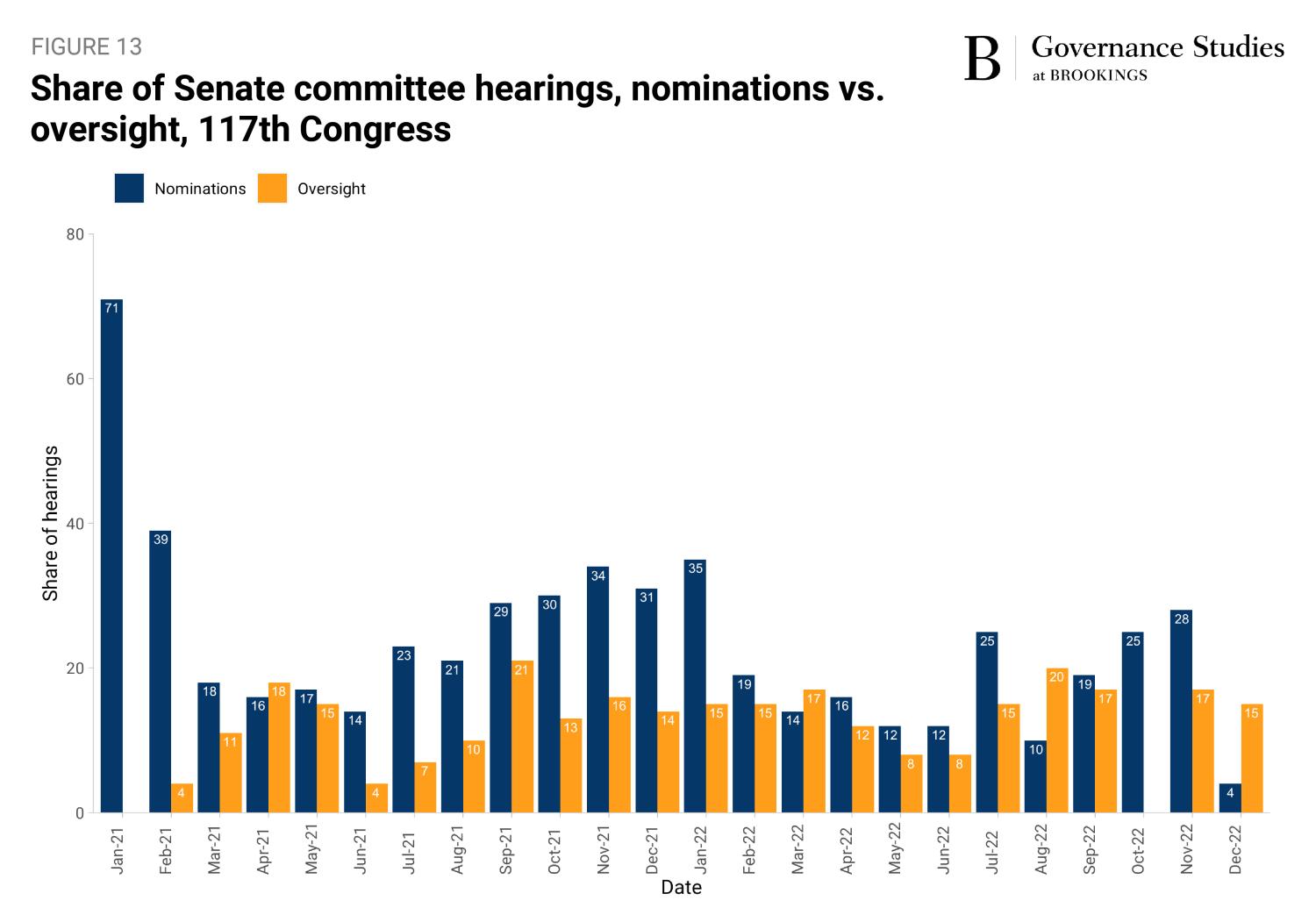

In Figure 13, we see a comparison, by month, of the share of Senate committees’ hearings that involved nominations (in blue) versus oversight of the executive branch (in orange) in 2021 and 2022. (The residual category is hearings that were neither executive branch oversight nor related to nominations.) In more than 80% of the months, the share of hearings that concerned nominations was greater than the share of executive branch oversight hearings; the former exceeded the latter by an average of 11 percentage points. As we would expect from a Senate charged with staffing up a new presidential administration, this focus on nominations over executive branch oversight was especially present in 2021, with only one month (April) where the share of hearings devoted to oversight (18%) slightly exceeded the share involving nominations (16%). Overall, in 2021, the average difference in the share of hearings that involved nominations versus executive branch oversight in a month was 18 percentage points; in 2022, it fell to five percentage points. These trends provide support for the notion that committees’ oversight choices can be constrained by other business on their agendas.

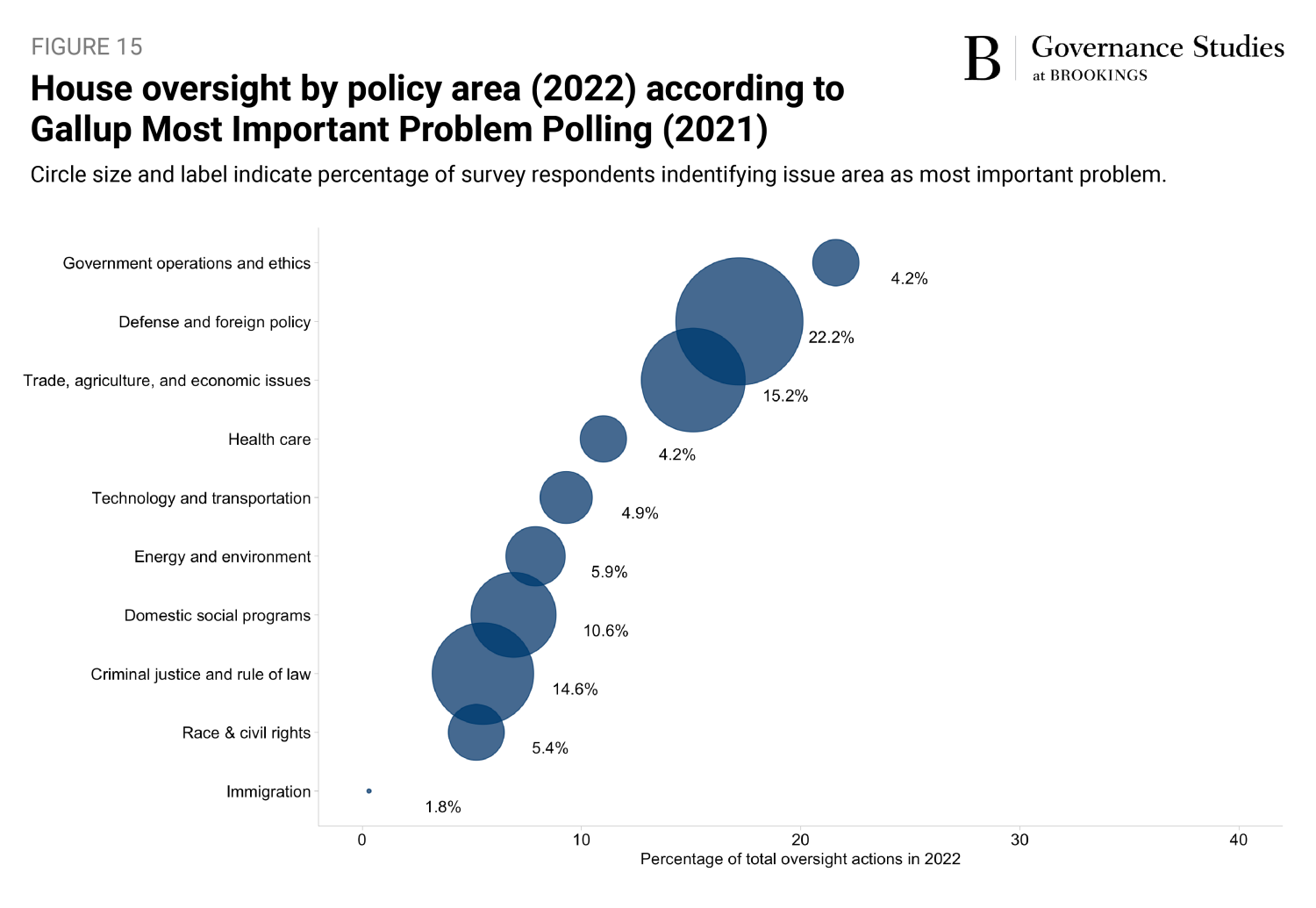

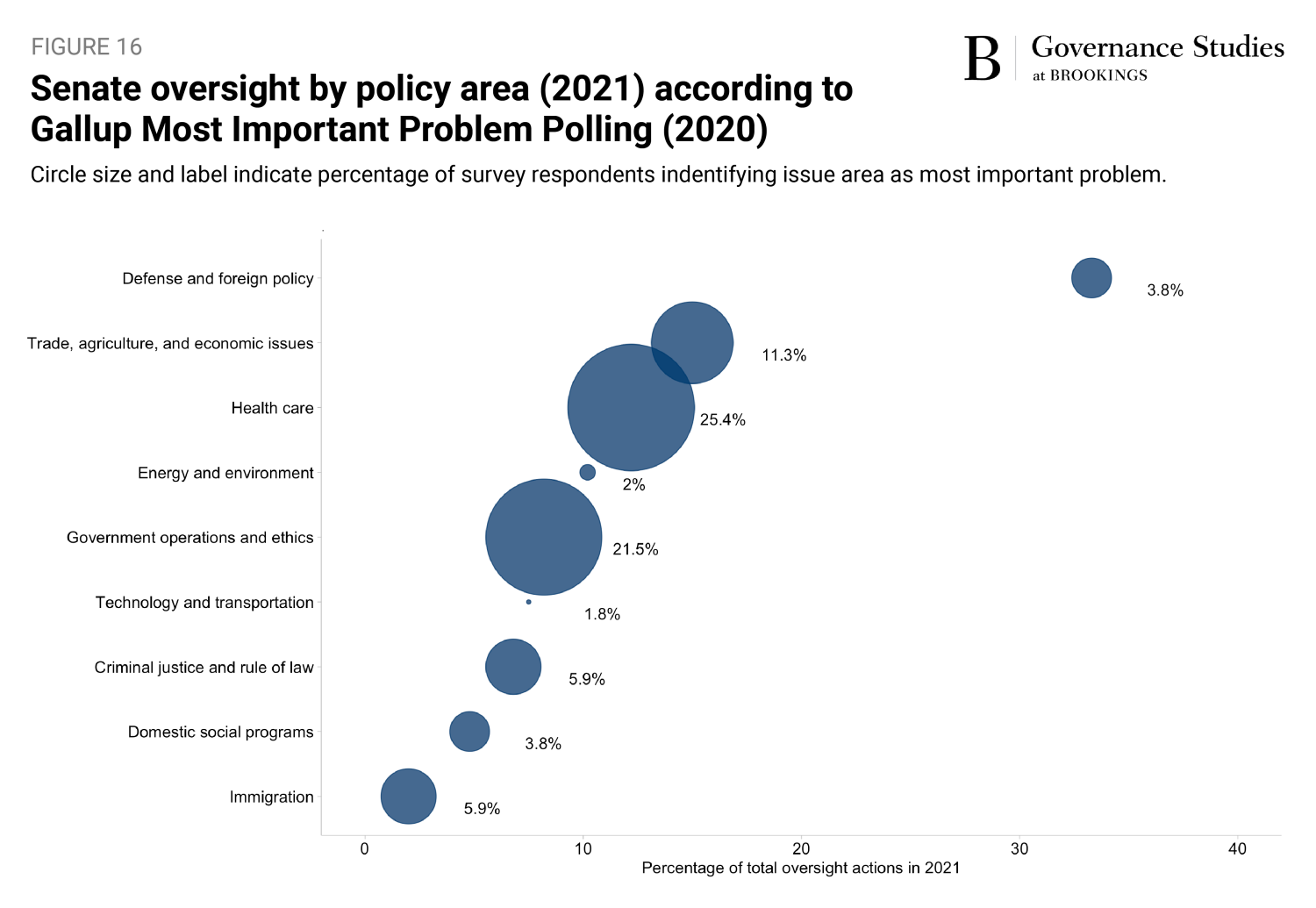

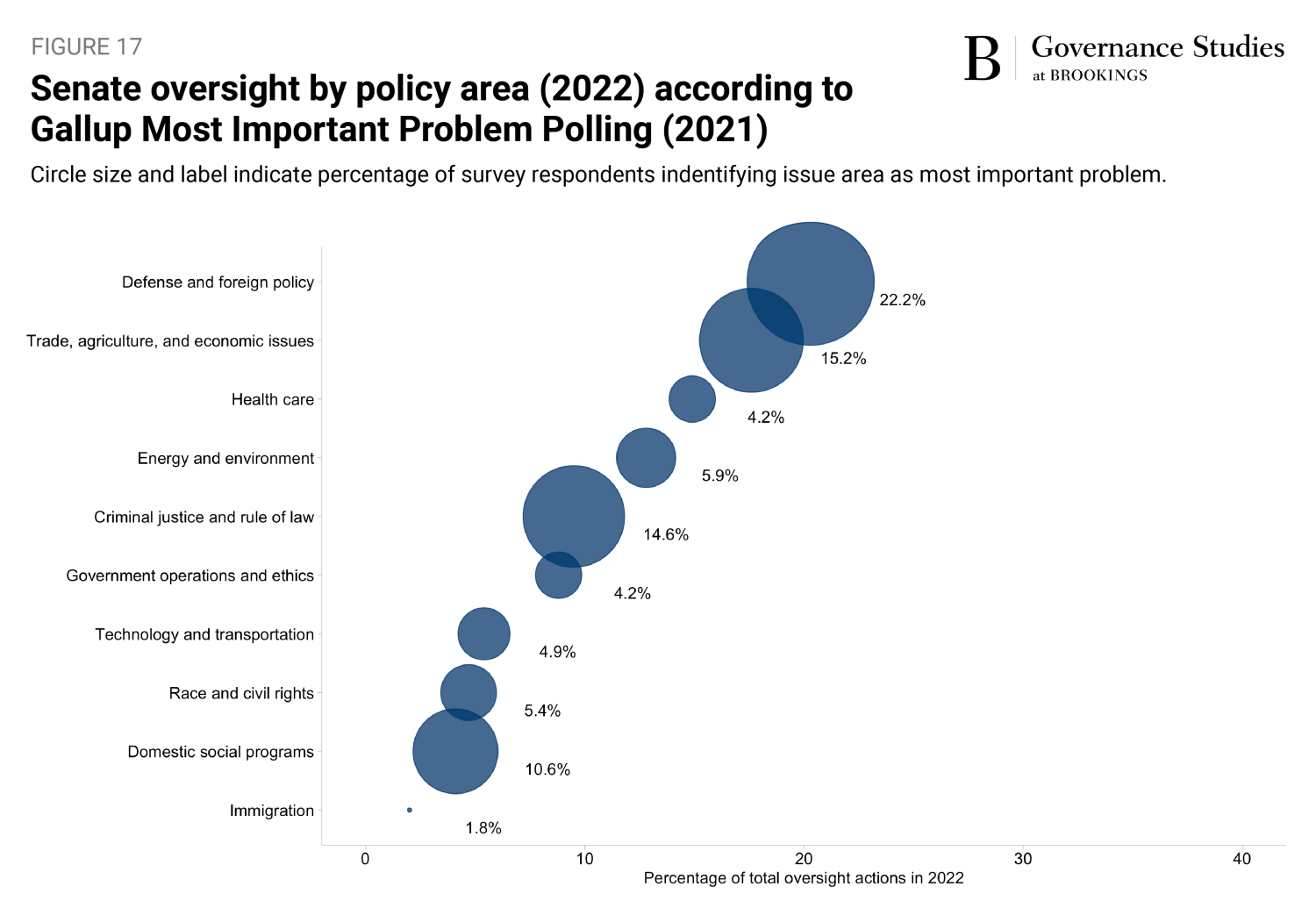

In addition to prioritizing among different types of tasks—such as processing nominations versus conducting oversight hearings—committees must also make choices about which issues on which to focus. While evaluating the quality of oversight is difficult, one useful measure is the degree to which Congress is focusing its oversight energy on the topics that are most important to the public.24 To investigate this, we use data from the Gallup Poll, collected and coded by the Policy Agendas Project using the same policy topic codes that we use to categorize oversight, on the share of survey respondents identifying a given issue as the “most important problem” facing the country; to allow Congress time to respond, we compare data on the public perceptions in a given year to oversight activity in the following year.

Figures 14, 15, 16, and 17 display this relationship for the House and Senate, respectively. If there was a perfect correlation between the amount of attention committees and subcommittees in each chamber devoted to various issues in the context of executive branch oversight and the degree to which the public assesses those same policy areas as the most important problems facing the country, the smallest circles would be in the lower left-hand corner of each graph. Proceeding across the x-axis from left to right and moving up the y-axis, the circles would get increasingly larger, with the largest, ultimately, in the upper right-hand corner.

In our study of executive branch oversight in the House in the 116th Congress, we found weak, but positive, correlations between the public’s assessment of the most important problem facing the country in one year and the level of oversight in the following year (0.43 for 2019 and 0.32 for 2020).25 Examining the 117th Congress across both chambers, the picture is more mixed. In the first year of the Congress (2021), in both chambers, the policy area to receive the most oversight attention was Defense and Foreign Policy—a topic that was assessed as the most important problem by relatively few survey respondents in 2020. In contrast, the issue rated as the most important problem by the largest share of respondents in 2020—health care—ranked third in terms of oversight attention, but with less than half of the focus given to defense issues. In 2022, by contrast, we see a relationship in the House similar to that of the 116th Congress (a correlation coefficient of 0.35) and a stronger, positive association in the Senate (a correlation coefficient of 0.66). Combining these data with that from the 116th Congress, we find that Congress does tend, at least at times, to pay attention to the same issues in its oversight efforts as the public reports caring about most.

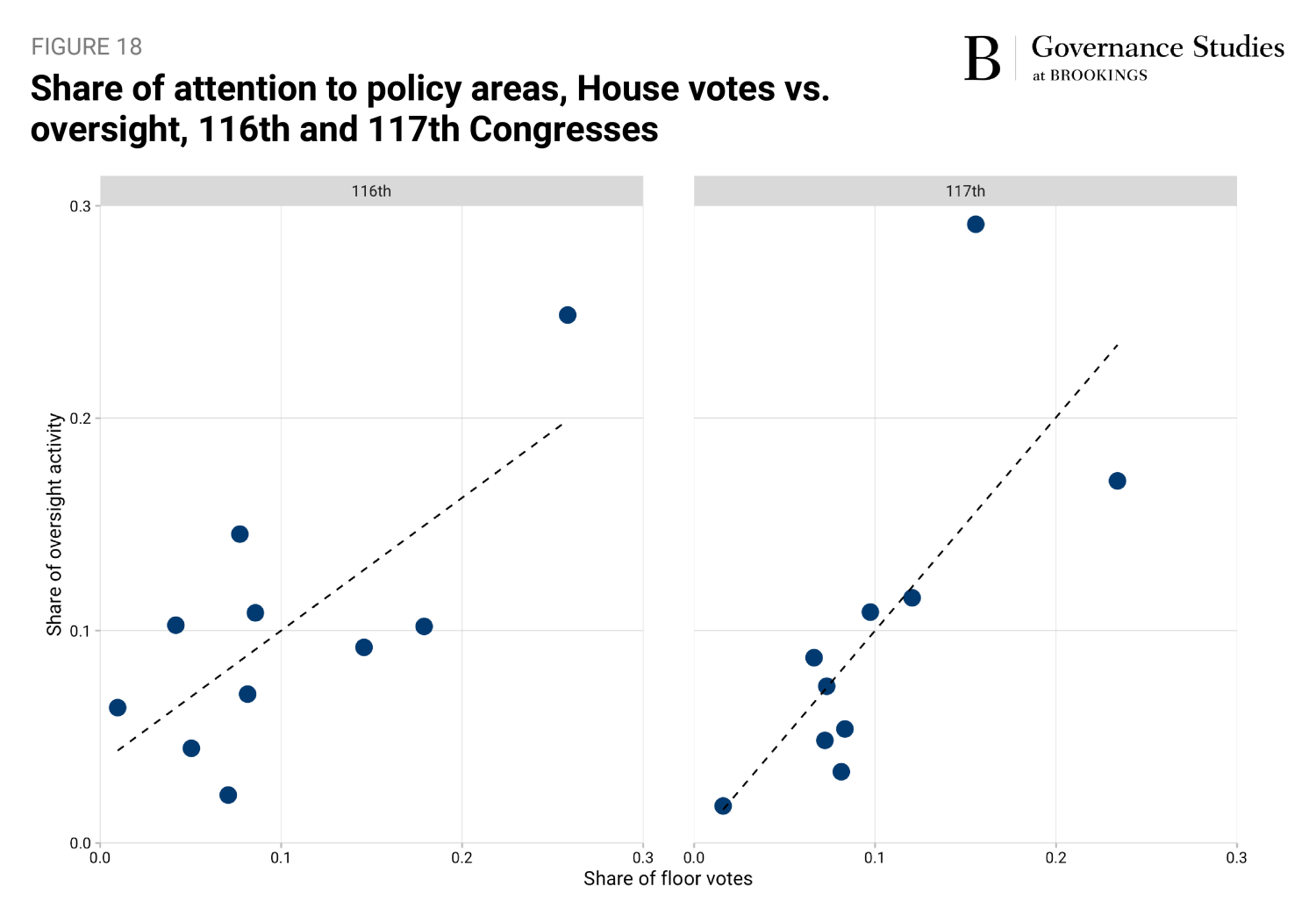

Choices about the areas in which to exercise executive branch oversight authority are affected by dynamics beyond considerations about the public’s priorities. Research suggests that, as the floor agenda—especially in the House—is being increasingly set by party leaders, committees are more likely to try to exercise their power through oversight.26 What we see in the 116th and 117th Congresses, however, is that in the House, committee leaders often devote their oversight energy, at least as related to the executive branch, to the same issues on which their leaders are choosing to hold votes. In Figure 18, we see that issues that represent a larger share of the votes taken in the House (depicted on the x-axis) also tend to be the same issues on which committees devote more of their executive branch oversight activity. Data for the House in the 116th Congress is on the left, while data for the 117th Congress is on the right; a linear trend line displays the relationship between the two measures. The most significant outlier—the data point for which the share of oversight activity in the issue area is nearly twice the share of floor votes on the topic—involves defense and foreign policy in the 117th and is the result of the amount of activity related to the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 (discussed both above and below). Otherwise, however, it appears that committee chairs, collectively, were prioritizing various issue areas for executive branch oversight in generally the same ways their party leaders were focusing on issues for floor votes. Our data cannot address whether chairs were choosing which issues to examine because they were ones on which they were getting messages directing them to focus on them from their party leaders—but that is one possible explanation for the trend.

What we see in the 116th and 117th Congresses, however, is that in the House, committee leaders often devote their oversight energy, at least as related to the executive branch, to the same issues on which their leaders are choosing to hold votes.

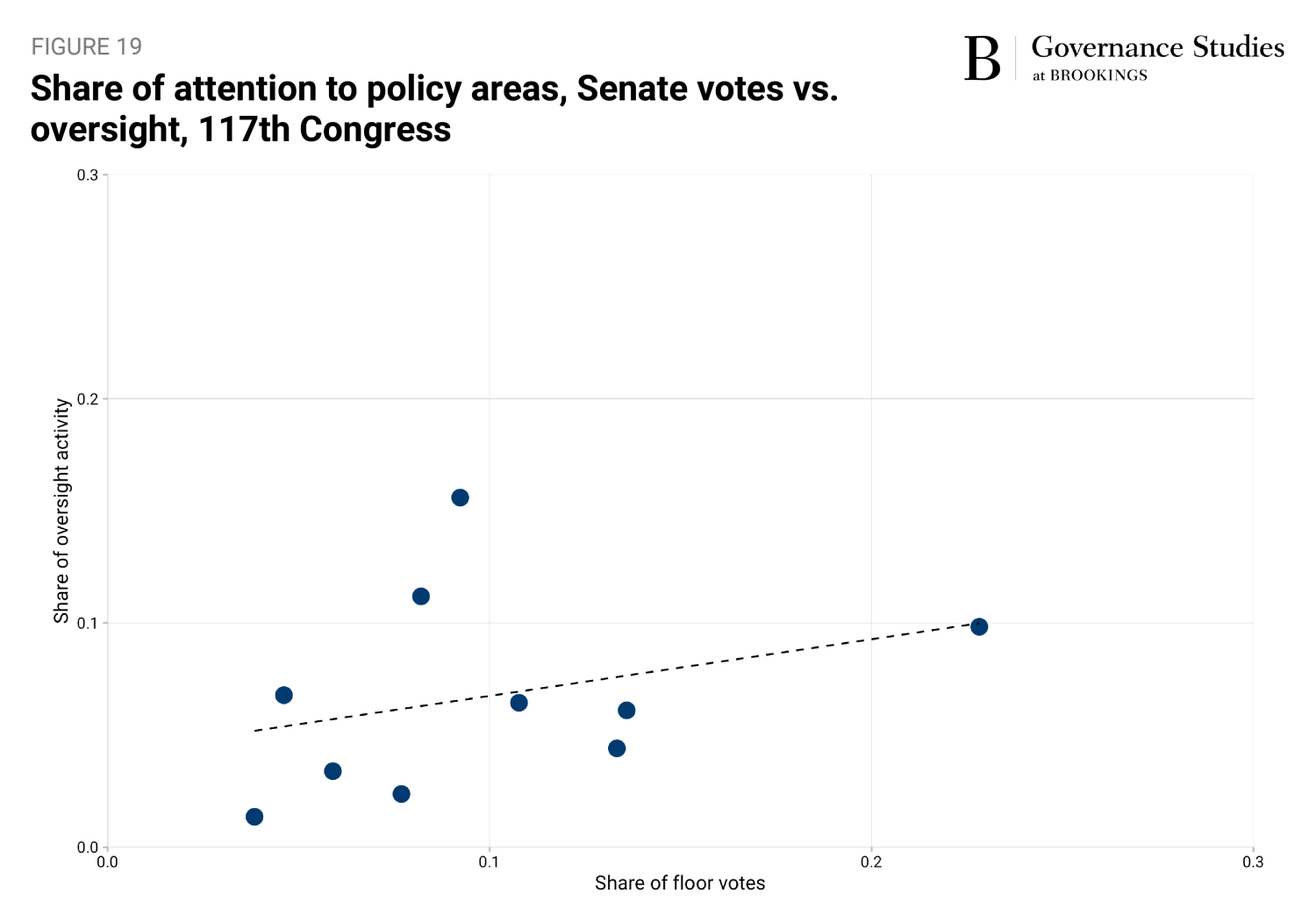

In Figure 19, we see the relationship between the share of non-nomination floor votes and the share of executive branch oversight activity in the Senate in the 117th Congress.27 While we see some policy topics for which more attention via oversight corresponds to more floor activity, the correlation is not as robust as in the House.28 Again, we cannot draw any clear conclusions about what is driving this difference, but one notable difference across the chambers in the 117th Congress is that, when the Senate devotes significant floor time to a given topic area, it tends to do by casting a large number of votes on a few bills addressing that policy. In comparison, the House tends to spread its attention out across a larger number of measures. In 2021 and 2022, the Senate devoted approximately 23% of its non-nomination floor attention to trade, agricultural, and economic issues, and more than 70% of those votes occurred on just three measures: the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021; the concurrent resolutions on the budget for fiscal year 2021 and 2022; and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. In the House, by comparison, government operations, as the policy area with the most floor attention, saw 123 separate measures receive votes in 2021 and 2022. As a result, the correspondence between areas of policy emphasis in the Senate may be more sensitive to leader choices about which specific pieces of legislation to bring to the floor than in the House.

Given the share of oversight activity related to the executive branch—especially in the House—that focused on investigating the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, it is worth reviewing some of the broader lessons of the inquiry conducted by the January 6th Committee for congressional oversight going forward.

The first and perhaps most obvious involved what the committee was able to accomplish. As Levin and Bean argue, in addition to focusing on issues of importance to the public, the quality of an investigation can also be measured by whether it “made use of appropriate investigative techniques, uncovered useful information, and was able to produce a consensus on the facts.”29 The committee certainly left questions insufficiently answered—including ones related to the broad failure of the intelligence community to prepare others for the possibility of extensive violence and of social media companies to address content that help mobilized individuals who participated in the attack.30 But despite these shortcomings, the panel undoubtedly used a broad range of investigative approaches to surface an extensive record of information about the insurrection. In conjunction with the release of its final report, which came in at more than 800 pages, the panel also released the transcripts of 271 witness interviews and more than 400 documents on file with the committee.31 The material released publicly was a subset of what one former staffer called “a tremendous volume of documents”;32 additional items obtained by the committee and not released to the public were shared with the Department of Justice.33 Though the investigation certainly did not “produce a consensus on the facts,” it served as the most comprehensive public inquiry to date into the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

The committee’s work also revealed important ways in which bipartisan buy-in can be important to the success of oversight efforts. The Select Committee was originally slated to have 13 members, five of whom were to be selected by the Speaker “after consultation with the minority leader.”34 Then-House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) initially proposed Reps. Jim Banks (R-Ind.), Rodney Davis (R-Ill.), Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), Kelly Armstrong (R-N.D.), and Troy Nehls (R-Tex.) as the GOP members of the panel.35 When Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) refused to seat Banks and Jordan, McCarthy responded by pulling all five of his picks.36 Pelosi, who had already selected Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) to join the committee, subsequently added Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) to the panel, bringing its makeup to seven Democrats and two Republicans.37

Though the investigation certainly did not “produce a consensus on the facts,” it served as the most comprehensive public inquiry to date into the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

Reporting at the conclusion of the committee’s work suggests that the inclusion of these two Republicans—especially Cheney—was an important ingredient in its success. The cooperation of several key witnesses, including former White House aides Cassidy Hutchinson and Sarah Matthews and former Speaker of the Arizona House of Representatives Rusty Bowers, was eased by Cheney’s participation in the investigation. As one senior staff member put it, “‘She was the reason they felt comfortable. They weren’t going to do it for Adam Schiff.’”38 While bipartisanship in oversight is often thought of as important for its ability to build credibility, the role of the Select Committee’s Republicans also reminds us that involvement of members from both parties can facilitate participation from a broader range of actors.39

Another lesson to be learned from the experience of the Select Committee is that resources matter. The panel was extremely well-resourced; data on disbursements made by House committees indicates that the January 6th Committee reported on roughly $11.8 million in spending in 2022. This compares to an average of approximately $8.3 million for spending reported on by all other House committees for the same year.40 Indeed, one staffer on the panel, interviewed after the conclusion of the committee’s work, described the situation as one where “the committee was constantly hiring.” As he put it, “it seemed like there was a new communications consultant every single day…you know, one day, there was one guy at a conference table with a laptop, and he just multiplied into, like, 12 people by the time I left.” The committee was, he argued, constrained by the time available to it to do its work but “money was no object.” The time limitation was significant, but within its fixed calendar, “the last six months” of the committee’s time was “dedicated…90% to hearings, report, writing, and making sure those findings reach the public.”41

We should not reasonably expect, however, that all the factors that made the committee effective are transferrable to other panels. Indeed, several are connected to its existence as a select, rather than a standing, committee. In addition to Speaker Pelosi’s ability to influence the committee’s membership to maximize its chances of achieving a certain set of goals, the panel’s entire purpose was to focus on a single investigation. Other congressional committees—even if they had similar resources—are unlikely to share the ability to devote all of their attention to one specific end.

Along the same lines, we should not reasonably expect re-election minded members of Congress from different political parties to consistently cede the spotlight to one another—as the January 6th Committee often did. Each member, Democrat and Republican, had the opportunity to lead or co-lead one of the panel’s hearings with reduced participation from their colleagues. This division of labor is highly unusual for a congressional committee, especially in the context of providing a member of the minority party the chance to lead a hearing—let alone one that appears on national television. There are certainly opportunities for committees to experiment with alternative hearing formats in order to encourage deep fact-finding; the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress piloted such an approach beginning in 2021 and recommended that other panels do the same.42 But our expectations about how broadly these changes could apply should be modest.43

Similarly, it is important to consider what the underlying goal of January 6th Committee’s oversight was. The committee certainly spent noticeable time and space—in hearings, floor speeches, and court filings alike—articulating what it saw as its “legislative purpose.” But there is reason to believe that emphasis was, at least in part, to steel itself against legal challenges to its work that relied on the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in Trump v. Mazars; in that case, the Court established a four-factor test for determining the appropriateness of a congressional subpoena for private information regarding a sitting president. Importantly, the case was not the first one in which the Supreme Court held that a subpoena must serve a valid legislative purpose, and the litigation related to the January 6th Committee largely involved different kinds of information than what was at stake in Mazars. But litigants used the decision as “more spaghetti to throw at the courtroom wall” in their efforts to challenge the committee’s legitimacy, and the panel repeatedly articulated a legislative purpose as it did its work.44

This division of labor is highly unusual for a congressional committee, especially in the context of providing a member of the minority party the chance to lead a hearing—let alone one that appears on national television.

This repeated emphasis on its legislative purpose notwithstanding, the committee’s primary objective was not, ultimately, to generate legislative solutions to the various policy problems that contributed to the insurrection at the Capitol. The panel itself could not report out legislation on its own, and the most significant measure passed in the 117th Congress connected to the committee’s work—reforms to the Electoral Count Act—was driven primarily by the Senate.45 As discussed above, however, other congressional committees are balancing their oversight responsibilities with legislative ones and face tradeoffs between devoting attention and resources across their functions.

A final lesson to be drawn from the January 6th Committee involves the limits of using litigation to backstop congressional oversight efforts. The 116th Congress provided several high-profile examples of attempts by House committees to obtain information, only to have their requests lead to protracted legal battles that were left unresolved at the end of the Trump administration.46 This included, for example, the fight over the House Ways and Means Committee’s ability to obtain President Trump’s tax returns, which began with a request from the committee’s chair, Rep. Richard Neal (D-Mass.), in April 2019 and did not conclude until more than three years later, when the panel voted to release the records in the closing days of the 117th Congress in December 2022.47

The January 6th Committee’s efforts were not immune from these forces. In September 2021, for example, the committee subpoenaed former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. After an initial period of cooperation, Meadows ceased working with the panel and instead sued the committee, its members, and Speaker Pelosi, claiming, among other assertions, that the committee did not have the power to seek information from him.48 The case was dismissed by District Court Judge Carl Nichols almost 11 months later without resolving all of the legal questions regarding Meadows’ cooperation and essentially too late for the committee to pursue additional legal avenues for forcing his compliance.49

In the contemporary era, majority control of the House and Senate switches more frequently than in earlier periods.50 As a result, committees should expect that, if their investigative priorities aren’t shared by the other party, they will have a single Congress to complete their oversight work; this is especially likely to be true of inquiries, like the one into the Jan. 6 insurrection, where high-profile members of the other party are the subject of the probe. Given these dynamics, relying on federal courts to backstop the investigative powers of Congress is likely to be a continued challenge.

The effective time limits imposed on many investigations by shifts in party control of the House and Senate is not the only way in which partisan dynamics shape congressional oversight. As we see in the data presented above, congressional committees tend to focus less of their attention on overseeing the executive branch when the chambers are controlled by the same party as the White House. To be sure, this is not a new finding, but the data we analyze here serves as a contribution to a growing body of evidence documenting this pattern. This tendency to focus less on overseeing an executive branch headed by a president of the same party as congressional majorities is certainly, at least in part, due to a desire to engage in partisan “team play” and to avoid embarrassing the highest-profile member of one’s party.

Partisan dynamics also filter, at least to some degree, into the issues on which Congress appears to devote its attention in the context of executive branch oversight. In the House, in both the 116th and 117th Congresses, we saw that the policy areas on which committees focused their oversight activities were often the same ones on which their party leaders chose to hold votes on the floor. And while the January 6th Committee was, as discussed above, a bipartisan endeavor, devoting significant resources to a deep inquiry into the events of that day was clearly a high priority of the House’s Democratic leadership.

Exploring congressional oversight of the executive branch is not only important because it demonstrates some of the various ways that partisanship shapes the behavior of the legislature but because congressional committees have limited resources—not just financial, but also in terms of time. Assessing how much attention they devote to oversight versus other responsibilities helps us understand how panels prioritize their various functions. Senate committees choosing to focus on processing nominees, especially in 2021, both reminds us of the chamber’s particular responsibilities as part of the advice and consent process and illustrates the importance of confirmation politics in a highly polarized period. Oversight is but one piece of Congress’s duties, but understanding it is vital to a full picture of the health of the legislative branch in our separation of powers system.

While an overview of our approach to data collection is provided above, interested readers may find additional details useful.

For hearings in the House, we used the hearings calendar available in the House of Representatives Committee Repository to obtain information about the title of each hearing, the committee or subcommittee holding the hearing, and the identities and affiliations of all witnesses appearing at the hearing. For letters, we compiled a list of the web pages on which House committees post press releases and additionally, in some instances, a specific list of the letters the panel has sent. (While committees are not required to make the letters that they send public, on relatively few occasions we were made aware of the existence of a letter that was not captured through our data collection strategy.) The Senate lacks a single source for all hearings, so a web page-based strategy was used for both hearings and letters for that chamber.

For each available letter, we recorded information about the sending committee or committees, the individual members of Congress who signed the letter, the topic of the letter, and the identity and affiliation of the recipient. Importantly, we only collected letters sent on behalf of a committee or subcommittee and that were signed by the chair of the panel in question. When a letter was also signed by other members of either party, we recorded that information. But we do not include letters sent by only members of the minority party. As oversight expert Morton Rosenberg explains, “…no ranking minority members or individual members can start official committee investigations, hold hearings, issue subpoenas, or attend informal briefings or interviews held prior to the institution of a formal investigation…Individual members may also seek the voluntary cooperation of agency officials or private persons. But no judicial precedent has recognized the right of an individual member, other than the chair of a committee, to exercise the authority of a committee in the oversight context.”

Our two-tiered “keyword/key witness” approach was applied as follows. Primary keywords included “oversight,” “investigate,” “examine,” “review,” “supervision,” “inefficiency/efficiency,” “abuse,” “transparency,” “accountability,” “waste,” “fraud,” “abuse,” “mismanagement,” and “implementation,” as well as variants of these words. (If a hearing involved an agency budget review, we did not consider it to be oversight.) GAO officials and officials in agency Offices of the Inspector General were primary witnesses or letter recipients.

We also compiled secondary keywords and key witness/recipients, which signaled possible inclusion as oversight but warranted more scrutiny. These included “update,” “effects,” “preparation,” “improve,” and agency “actions,” as well as, for witnesses/recipients, current and former heads of agencies or agency subunits; individuals affected by program mismanagement; and individuals or organizations with knowledge of White House or executive branch operations. To apply this definition consistently and carefully, each piece of potential oversight material was reviewed by two coders working independently; a third coder adjudicated any disputes.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The development and maintenance of the database analyzed in this paper would not have been possible without outstanding assistance from a number of individuals. Cary Lynne Thigpen assisted with background research and conceptual development, and Rachel Orey provided invaluable assistance with developing our data collection workflow. Jackson Gode coordinated and supervised data collection, coding, and analysis for the 116th Congress and the early months of the 117th. DeKiah Baxter, Gavin Downing, Isabella Gelfand, Lily Gong, Emily Larson, Mohammed Memfis, Shruti Nayak, Scarlett Neely, Christian Potter, David Ton, Kennedy Teel, and Grace Zandi collected and coded data. We also benefitted, in the development of the Oversight Tracker for the 116th Congress, from conversations with Dan Diller and Jamie Spitz at the Lugar Center and, in preparation of this report, from feedback from Maya Kornberg.

Support for this publication was generously provided by the Democracy Fund and the Hewlett Foundation.

-

Footnotes

- Douglas L. Kriner and Eric Schicker, Investigating the President: Congressional Checks on Presidential Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017).

- Frances E. Lee, “Presidents and Party Teams: The Politics of Debt Limits and Executive Oversight, 2001-2013,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 43.4 (December 2013): 775-791.

- Maya L. Kornberg, Inside Congressional Committees: Function and Dysfunction in the Legislative Process (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023), 147.

- Alexander Bolton and Sharece Thrower, Checks in the Balance: Legislative Capacity and the Dynamics of Executive Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022).

- See, for example, Victoria Bassetti, “How to Fix Congressional Oversight,” Brennan Center for Justice, January 2015 <https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-fix-congressional-oversight>.

- Nicholas G. Napolio and Janna King Rezaee, “Extremists and Participation in Congressional Oversight Hearings,” Center for the Study of the Administrative State Working Paper 20-20, George Mason University, October 2020 <https://administrativestate.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Napolio-Rezaee-Extremists-and-Participation-in-Congressional-Oversight-Hearings.pdf>.

- Jason MacDonald, “Partisan Trends in Congressional Oversight, 1987-2016,” Extensions: A Journal of the Carl Albert Center, Winter 2019.

- Kornberg 2023.

- Ayse Eldes, Christian Fong, and Kenneth Lowande, “Information and Confrontation in Legislative Oversight,” Working Paper, July 2022 <https://lowande.polisci.lsa.umich.edu/fle-qualities.pdf>.

- Jonathan Lewallen, Committees and the Decline of Lawmaking in Congress (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020).

- For analyses of the data from the first year of the 116th Congress, Molly E. Reynolds and Jackson Gode, “Tracking Oversight in the House in the 116th Congress,” Wayne Law Review, 66.1 (2020): 237–258. For an analysis of the full 116th Congress, see Molly E. Reynolds and Jackson Gode, “Divided Government, Disruptive President: Congressional Oversight of the Executive Branch in the 116th Congress,” The Brookings Institution, July 2021.

- “Congressional Oversight Index.” Interactive, The Lugar Center <oversight-index.thelugarcenter.org/hearings>; Brian D. Feinstein, “Who Conducts Oversight? Bill-Writers, Lifers, and Nailbiters,” Wayne Law Review, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 127–48. Robert J. McGrath, “Congressional Oversight Hearings and Policy Control,” Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 349–376.

- For oversight activity in the 116th House, we also required that the conduct being investigated have occurred since Nov. 8, 2016, and concern executive branch conduct, rather than campaign activity involving President Trump. For the 117th Congress, we retained the exclusion for campaign activity but included actions that examined executive branch activity during the prior administration. As a result, investigative work related to the involvement of President Trump and other executive branch-affiliated individuals in the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, are included in our definition of executive branch oversight here.

- The Policy Agendas Project at the University of Texas at Austin, 2017. www.comparativeagendas.net.

- “Tracking House oversight in the Trump era: Methodology,” March 2019 <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/gs_20190321_tracking_oversight_trump_era_methodology.pdf>.

- Kornberg 2023; Kevin M. Leyden, “Interest Group Resources and Testimony at Congressional Hearings,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20.3 (August 1995): 431-439.

- Reynolds and Gode 2021.

- Pamela Ban, Ju Yeon Park, and Hye Young You, “How Are Politicians Informed? Witnesses and Information Provision in Congress,” American Political Science Review 117.1 (February 2023): 122-139.

- Reynolds and Gode 2021.

- Annie Karni and Catie Edmondson, “House Committee Budgets Swell as Republicans Plan Road Shows,” New York Times, March 6, 2023, p. A16; William T. Egar, “House Committee Funding: Description of Process and Analysis of Disbursements,” Congressional Research Service, November 8, 2018.

- Lewallen 2020.

- E.J. Fagan and Zachary A. McGee, “Problem Solving and the Demand for Expert Information in Congress,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 47.1 (February 2022): 53-77.

- A notable exception to this need to build a 60-vote coalition was, of course, the budget reconciliation process; Democrats used that set of filibuster-proof procedures twice in the 117th Congress to pass significant legislation (the American Rescue Plan Act and the Inflation Reduction Act).

- Carl Levin and Elise J. Bean, “Defining Congressional Oversight and Measuring Its Effectiveness,” Wayne Law Review, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 1–22.

- Reynolds and Gode 2021.

- Lewallen 2020.

- All nominations are categorized as “government operations” votes, and the need to fill many vacant appointee positions at the start of a new administration, as in 2021, biases the roll call record in favor of that specific issue.

- Mathematically, the correlation coefficient for both the 116th and 117th Houses (approximately 0.74 in both cases) is roughly twice the size of the correlation coefficient for the 117th Senate (0.32).

- Levin and Bean 2018, p. 18.

- For more on the omissions from the Committee’s final report, see, for example, Quinta Jurecic, “The Dangerous Omission in the Jan. 6 Committee’s Report Summary,” Lawfare, December 20, 2022. <https://www.lawfareblog.com/dangerous-omission-jan-6-committees-report-summary> and Cat Zakrzewski, Cristiano Lima, and Drew Harwell, “What the Jan. 6 Probe Found Out About Social Media, But Didn’t Report,” Washington Post, January 17, 2023.

- The final report, interview transcripts, and other materials released by the committee are available as part of the Select January 6th Committee Final Report and Supporting Materials Collection, U.S. Government Publishing Office, December 2022 <https://www.govinfo.gov/collection/january-6th-committee-final-report?path=/gpo/January%206th%20Committee%20Final%20Report%20and%20Supporting%20Materials%20Collection/Supporting%20Materials%20-%20Documents%20on%20File%20with%20the%20Select%20Committee>

- Dean Jackson, interview with Quinta Jurecic, Lawfare Podcast, podcast audio, February 8. 2023, <https://www.lawfareblog.com/lawfare-podcast-jan-6-committee-staffer-social-media-and-insurrection>.

- Kyle Cheney, “Justice Department reveals it has Jan. 6 select committee files that the panel opted not to release to the public,” Politico January 12, 2023 <https://www.politico.com/minutes/congress/01-12-2023/jan6-panel-withholds-some-evidence/>.

- H. Res. 503, 117th Congress, 1st session.

- Chris Marquette, “McCarthy Names Five Choices for Jan. 6 Select Committee,” Roll Call July 19, 2021.

- Marianna Sotomayor, Jacqueline Alemany, and Karoun Demirjian, “Bipartisan House Probe of Jan. 6 Insurrection Falls Apart after Pelosi Blocks Two GOP Members,” Washington Post, July 21, 2021.

- Jesse Naranjo and Olivia Beavers, “Pelosi Taps Kinzinger to Serve on Jan. 6 Select Panel,” Politico, July 25, 2021.

- Robert Draper and Luke Broadwater, “Inside the Jan. 6 Committee,” New York Times Magazine, January 1, 2023, p. 31.

- Levin and Bean 2018.

- Because some spending for 2022 by the Select Committee was not reported on until 2023, this does not represent a full accounting of its spending for the year; it also does not include spending for 2021, as the committee was not constituted until July of that year. For data cited here, see “Statement of Disbursements of the House, as Compiled by the Chief Administrative Officer, October 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022,” H. Doc. 118-5, January 4, 2023.

- Dean Jackson interview.

- “Final Report,” Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, H. Rpt. 117-646, 117th Congress, 2nd sess., December 2022.

- Quinta Jurecic and Molly E. Reynolds, “The Lessons—and Limits—of the Jan. 6 Committee,” Lawfare, August 5, 2022 <https://www.lawfareblog.com/lessons%E2%80%94and-limits%E2%80%94-jan-6-committee>.

- Quinta Jurecic and Molly E. Reynolds, “Mazars Creep and the Jan. 6 Committee,” Lawfare, February 24, 2022 <https://www.lawfareblog.com/mazars-creep-and-jan-6-committee>.

- Carl Hulse, “Voting Flaw Exposed by Jan. 6 Spurred Senators,” New York Times, December 23, 2022, p. A1.

- Reynolds and Gode 2021.

- Jim Tankersley, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner, “6 Years’ Worth Of Trump Taxes Show Big Losses,” New York Times, December 31, 2022, p. A1.

- Caitlyn Kim, “Mark Meadows Will Stop Cooperating with the Jan. 6 Panel,” NPR, December 7, 2021 <https://www.npr.org/2021/12/07/1062098646/mark-meadows-stop-cooperating-jan-6-panel-capitol>; Betsy Woodruff Swan, Kyle Cheney, and Josh Gerstein, “Meadows Sues Pelosi, Jan. 6 Panel and its Members,” Politico, December 8, 2021.

- Luke Broadwater, “Suit by Meadows Seeking to Block Jan. 6 Panel’s Subpoenas Is Dismissed,” New York Times, October 31, 2022.

- Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).