This blog is part of the “School Discipline in America” series. In this series, experts from Brookings and RAND explore how U.S. public schools approach student discipline and educators’ perspectives on disciplinary approaches and challenges, providing key insights into contemporary debates over student discipline practices and policies.

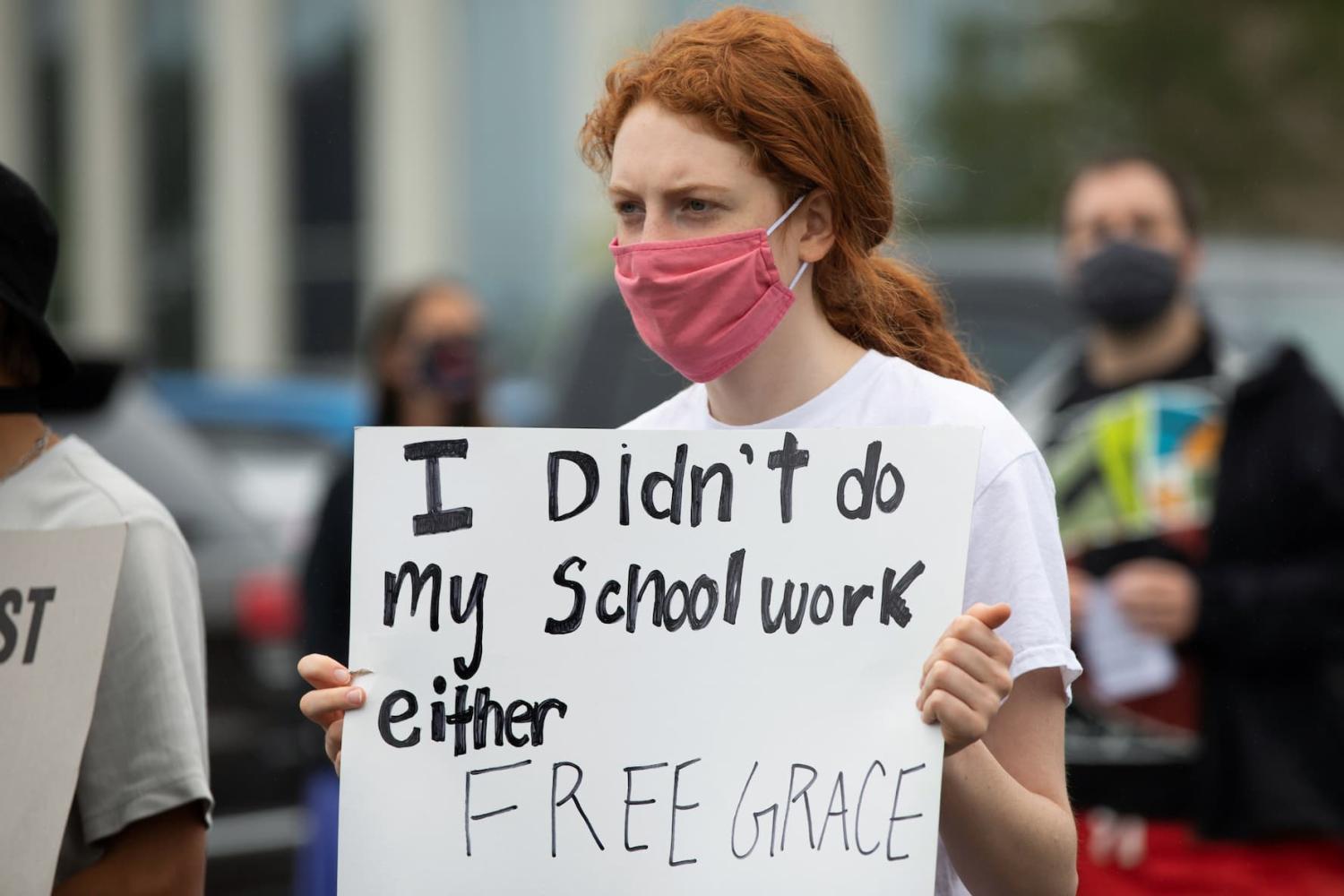

Schools across the U.S. have been reporting increased student misbehavior ever since students returned to in-person schooling following the COVID-19 pandemic-related school closures. While much about the heightened student behavioral challenges facing schools remains unknown, experts suspect students are still recovering from the trauma of the pandemic and struggling from missed social and emotional development opportunities.

In response to these concerning trends, lawmakers in at least eight states are working to make it easier for teachers and principals to remove misbehaving students from school. The policy proposals put forth by these lawmakers represent a stunning about-face after 10+ years of state- and district- led reforms to promote less-punitive approaches like restorative justice practices as alternatives to suspensions. These reforms were intended to replace the types of strict discipline policies that proliferated in the 1990s and early 2000s, which emphasized suspensions and expulsions as the solution to schools’ discipline problems. But heightened student misbehavior is now raising questions about the effectiveness of these reform efforts.

Supporters of these more punitive proposals argue that recent reforms have made schools too lenient and that less-punitive approaches aren’t effectively curbing disruptions. Opponents argue that reform efforts were stymied by a variety of factors—inadequate resources for implementation, educator buy-in, and ultimately pandemic disruptions—and that a return to strict discipline policies will wrongly punish kids who are dealing with lingering mental health issues and struggling to readjust to the norms of in-person schooling.

Have schools become too lenient when it comes to student misbehavior? Can less-punitive approaches to student discipline work, especially in the context of pandemic recovery?

Over the last year, we’ve used survey data from principals to understand the current landscape of school discipline policies and practices, principals’ perspectives on suspensions, and what principals say they need to reduce student misbehavior. In this post—the final installment in this series—we use findings from this work and a review of student discipline research to reflect on school discipline in the context of pandemic recovery. We also discuss what else state and district leaders can do to reduce student misbehavior and improve school climate.

More than a half dozen states are considering a return to stricter student discipline policies, including four that have already done so

In 2023 state legislative sessions, at least eight states introduced policy proposals related to school discipline, including four states (Arizona, Kentucky, Nevada, and West Virginia) where the bills have already become law. Although the specifics differ (see Table 1), these bills broadly aim to give educators more discretion to suspend and expel misbehaving students. This includes more discretion over which types of misbehaviors can be punished (e.g., a North Carolina bill would allow suspensions for cursing and dress code violations); the conditions under which schools can suspend students and for how long (e.g., Nevada’s new law removes a requirement that schools first attempt restorative justice practices); and which students can be suspended (e.g., a new Arizona law lowers the minimum suspension grade from 5th grade to kindergarten). Two states (Florida and Nebraska) would also loosen rules guiding when educators are allowed to physically restrain students.

Table 1. State legislation related to student discipline introduced in 2023

|

State |

Proposed Legislation |

Signed into law? |

|

Arizona |

House Bill 2460: Allows K-4 students (who are at least seven years old) to be suspended for up to two days (for no more than 10 days total in a school year). K-4 students can be suspended if their behavior is “determined to qualify as aggravating circumstances and the pupil’s behavior is persistent and unresponsive to targeted interventions.” | |

|

Florida |

Senate Bill 244: Would allow teachers to remove “disobedient, disrespectful, violent, abusive, uncontrollable, or disruptive” students from their classrooms, and to use “reasonable force” to protect themselves or others from injury. |

No |

|

Kentucky |

House Bill 538 : Students removed from the same classroom three times in a 30-day period may be suspended for being “chronically disruptive.” Principals have the discretion to determine whether the student should remain in the classroom. Principals can permanently remove students from a classroom if they determine that their presence would “chronically disrupt the education process for other students.” | |

|

Nebraska |

Legislature Bill 811: Would allow teachers to use “reasonable physical intervention to safely manage the behavior of a student.” Would protect school personnel who engage in physical restraint from administrative or professional discipline if such physical intervention was “reasonable.” Requires school staff to receive behavioral awareness and intervention training. |

No |

|

Nevada |

Assembly Bill 285 and Assembly Bill 330: Reverses a 2019 law requiring school districts to adopt a restorative justice plan. Removes requirements that schools have individual behavioral plans in place before a student can be suspended or expelled. Lowers the age schools may suspend students from 11 to six. Requires a “plan of reinstatement” after students are suspended or expelled, and a “progressive discipline plan.” | |

|

North Carolina |

House Bill 188: Would allow students to receive long-term suspensions for “inappropriate or disrespectful language, noncompliance with a staff directive, dress code violations, and minor fights that do not involve weapons or injuries.” |

No |

|

Texas |

Senate Bill 245: Would allow teachers to remove students if a student is “unruly, disruptive, and abusive” and their behavior is impeding the teacher’s ability to teach. Teachers can remove a student after a single “disruptive” incident. |

No |

|

West Virginia |

House Bill 2890: Allows teachers to remove students from the classroom for disorderly conduct, willful disobedience, or cursing at a school employee. Students exhibiting persistently disruptive behavior may be transferred to alternative educational settings. Middle and high school teachers may remove disruptive students for the day; students removed three or more times in a month for disruptive behaviors may be suspended. |

What does the research say about these policy ideas?

Based on our review of the research, we believe a return to stricter discipline policies (such as those described in detail in Table 1) would sacrifice the learning, development, and well-being of one group of kids for the potential benefit of another. And the groups most likely to bear the burden of a return to stricter discipline policies are the same groups who were most harmed by similar policies the last time around—Black students and other students of color, as well as students with disabilities. Making matters worse, these groups are still recovering from being among those most negatively affected by the pandemic and pandemic-related disruptions to schooling.

Here’s how we came to this conclusion:

An abundance of research indicates that strict discipline policies that promote the use of suspensions as punishment—like the types of discipline policies that proliferated in the 1990s/2000s and the ones proposed in the 2023 legislative sessions—do not reduce student misbehavior, nor do they make schools safer. What’s more, suspension-promoting policies often led to sharp increases in suspension rates, especially for students of color. In fact, research on the ineffectiveness of strict discipline policies and the resulting over-suspension of Black, Native American, and Latino students was used as motivation for the discipline reform efforts that these new policy proposals aim to reverse.

The research identifies at least three reasons why strict discipline policies don’t work for misbehaving students:

- The theory of change is deeply flawed. These policies are based on a model of deterrence that assumes that students are rational decisionmakers who will take into account the known harsh consequences associated with breaking school rules (like getting suspended or expelled) before taking an action in violation of school rules. But kids’ brains aren’t capable of the type of reasoned thinking that a deterrence model of discipline requires. Experts also stress that “behavior is skill, not will,” meaning that relying on punishment to improve student behavior wrongly assumes that students have the skills (e.g., frustration tolerance and emotional regulation) to meet school’s behavioral expectations in the first place.

- Increased discretion over who to remove from the classroom, for what reason, and how to punish them only leaves more room for conscious and unconscious biases to factor into educators’ decision-making. Discipline reforms of the 2010s sought to limit the impact of biases by defining, in law or policy, when students could not be suspended or expelled. They did so amid research documenting the prevalence of racial discrimination in educators’ disciplinary decision-making, and other work showing that racial disparities are larger for infractions that rely on subjective assessments (e.g., infractions like disruption, disobedience, and willful defiance). For example, in 2011, North Carolina lawmakers formalized guidance outlining the types of infractions that could merit long-term suspensions that explicitly excluded subjective, nonviolent infractions like inappropriate or disrespectful language and “noncompliance” with staff directions.

- Suspensions harm students academically, in both the short and long run. Suspensions are associated with lower subsequent test scores, and lower rates of high school and college graduation. And research suggests that the more students struggle academically, the more likely they are to act out, creating a vicious cycle that won’t end until the student is pushed out of school altogether.

How strict discipline policies benefit non-misbehaving students—if at all—is far less clear. Proponents of recent bills (including local teachers’ unions in some states) argue that increased suspensions for misbehaving students are necessary to preserve the learning environment for non-misbehaving students. Some studies have found that non-misbehaving students’ outcomes improve when their misbehaving peers are removed. However, if suspensions do not improve the behavior of suspended students over the long run, this benefit to the learning environment could be short-lived. Indeed, other research finds a negative relationship between non-misbehaving students’ test scores and peers’ suspensions. Still others find no effect. All told, the question of how suspension-promoting policies affect non-misbehaving students remains unsettled in the research literature.

What can policymakers do to support schools in their efforts to address heightened student misbehavior instead of returning to strict discipline policies?

Principals have consistently said they need two things to reduce student misbehavior: better training for teachers and more funding. In a November 2021 survey, for example, only one-third of a nationally representative sample of principals said their teachers had been adequately trained by their teacher preparation programs to deal with student misbehavior and discipline. Similarly, when asked in a May 2022 federal survey what their schools need to better support student behavior and socioemotional development, trainings on supporting students’ socioemotional development (70%) and classroom management strategies (51%) were among principals’ top answers.

Beyond teacher training, principals also say they need more support for student and staff mental health (79%) and to hire more teachers and/or other staff (60%) to better support student behavior. More funding for mental health supports, in particular, stands out as an area where policymakers could offer schools support. Schools needed more mental health supports before the COVID-19 pandemic—and that need has only intensified since then.

Inadequate training and resources are also likely why reform efforts, including those aimed at promoting alternative practices like restorative justice (RJ) programs or Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), have stalled in some places. Research on the effectiveness of these two popular approaches—which our work shows became widespread in U.S. public schools over the last decade—suggests both are promising alternatives. A large body of research suggests that PBIS (a schoolwide program and set of practices that aim to make behavioral expectations clear and positively rewards students for following behavioral norms) reduce behavioral incidents and suspensions and improves school climate. While the literature on RJ programs—which aim to promote conflict resolution skills in lieu of punishment—is more nascent, early studies suggest similar positive effects on behavior and school climate. This is especially true in places where sufficient time and resources were dedicated to implementing either PBIS or RJ.

When proponents of stricter discipline policies argue that schools have become too lenient on student misbehavior, it’s possible they’re describing a real dynamic driven by inadequate implementation of alternative approaches. Put another way, if these programs haven’t been implemented well (or at all) and schools have done away with traditional forms of consequences, then students’ misbehaviors may in fact be going unchecked.

Students need more caring and supportive schooling environments, not more punitive ones

Figuring out how to prevent student misbehavior and improve school climate should be a top priority for state lawmakers. Instead of falling back on old approaches to student discipline that research has largely shown to be ineffective, policymakers should listen to what the vast majority of school leaders say they need: more resources for teacher-trainings, hiring of additional teachers and staff, and mental health supports. And given the promising track record of alternative approaches like PBIS and restorative justice—and the fact that implementation of these programs is already underway in a large share of K–12 public schools—policymakers should invest more resources to ensure their success.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Ayanna Platt for excellent research assistance for this blog post.

Rachel M. Perera is an alumna of the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a past employee of the RAND Corporation during which time she completed the majority of her contribution to this project. Perera remains an adjunct policy researcher with the RAND Corporation and received financial support from RAND to complete this project. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of the authors and do not represent positions or policies of the RAND Corporation, Brookings Institution, its officers, employees, or other donors. Brookings is committed to quality, independence, and impact in all its work.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).