This blog is part of the “School Discipline in America” series. In this series, experts from Brookings and RAND explore how U.S. public schools approach student discipline and educators’ perspectives on disciplinary approaches and challenges, providing key insights into contemporary debates over student discipline practices and policies.

Principals and their school leadership teams are often the final arbiters of discipline decisions in schools. When a student is written up for an infraction—in response to incidents ranging from talking back to a teacher to more extreme cases like fighting or bringing a weapon to school—principals typically decide both whether and how severely to punish the student. Disciplinary actions can range from sending a note home to the student’s parents to an after-school detention all the way up to a suspension or expulsion.

How do principals make decisions about how to address student misconduct? Sometimes their hands are tied: six in ten schools have zero-tolerance policies that dictate how principals should respond to certain infractions. However, these policies generally apply only to serious offenses like bringing a gun to school. For low-level offenses—which represent most disciplinary incidents in U.S. public schools—principals typically have a lot of autonomy to discipline students as they see fit. Unsurprisingly given this autonomy, research shows that principals vary significantly in how punitive they are and how much racial bias they exhibit in disciplining students.

Efforts to encourage principals to limit their use of excessively punitive disciplinary practices have been underway for more than a decade. These efforts are motivated by concerns that removing students from the classroom harms students’ educational trajectories and that the most severe punishments are disproportionately borne by students of color. Accordingly, schools’ use of suspensions and expulsions—commonly referred to as exclusionary discipline practices—have been steadily declining since peaking around 2010. And yet suspension rates remain high, especially for students of color.

So, why do principals continue to suspend and expel students? And for what purpose?

Given the central role that principals play in school discipline and the potential success of reform efforts, we sought to learn more about principals’ beliefs about school discipline. With colleagues at the RAND Corporation, we surveyed 1,080 public school principals across the United States in November 2021 using RAND’s nationally representative American School Leader Panel. Given that suspension rates are typically much higher in secondary schools (that is, middle and high schools) and in schools serving higher shares of racially minoritized students, we examined whether principals’ beliefs about school discipline vary by grade level and the racial/ethnic makeup of the school.[1] Here’s what we found.

Principals believe that the purpose of discipline is educational. Yet, few think suspensions achieve this goal.

Most principals (82%) agree or strongly agree that the primary purpose of discipline is to teach appropriate skills to students who misbehave. We interpret “teach appropriate skills” as teaching misbehaving students the skills necessary to avoid repeating those behaviors in the future. Exclusionary practices rely in part on the assumption that removing misbehaving students from school teaches them that their behavior was inappropriate and incentivizes them to avoid future disciplinary incidents. And yet, principals by and large do not believe exclusionary discipline achieves this goal: only 12% of principals agree or strongly agree that suspensions and expulsions allow students time away from school to reflect on—and presumably learn from—their behavior.

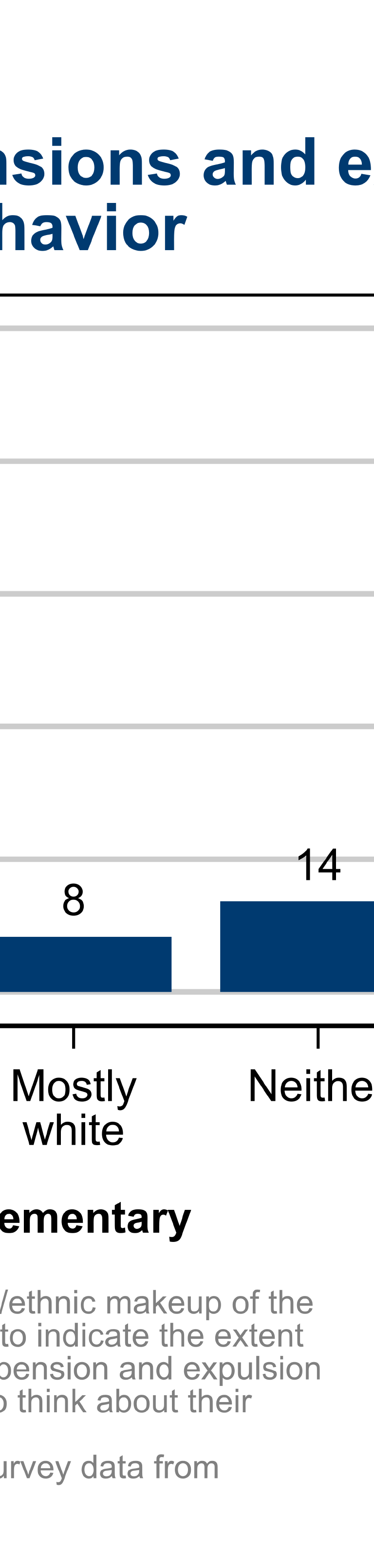

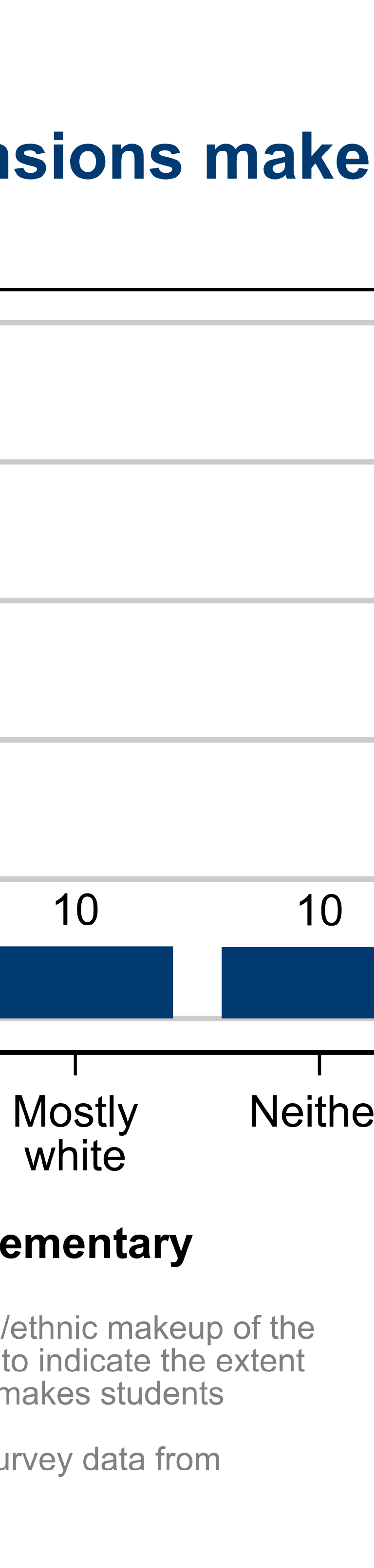

Principals’ skepticism that exclusionary discipline practices offer needed time for reflection holds regardless of school context (see Figure 1). In all school settings, fewer than one-third of principals hold this belief about the utility of exclusionary discipline. However, principals in majority-Black elementary schools are more likely than their counterparts in majority-White elementary schools to agree that suspensions and expulsions can encourage this type of skill building.

Few principals think suspensions accomplish other goals, such as preventing future misbehavior or preserving the learning environment for other students.

Exclusionary discipline practices may also serve purposes other than giving students time for reflection. Some researchers argue that exclusionary practices have a useful deterrent function. Others argue that the utility of these practices extends beyond simply limiting student misbehavior in that exclusionary discipline can be used to improve the learning environment for non-disciplined students by removing disruptive peers.

Principals’ responses to our survey suggest they don’t believe exclusionary discipline accomplishes either of these goals. A majority of principals (69%) agree or strongly agree suspensions and expulsions do not really solve discipline problems. Only 13% of principals feel they do, and the remaining 18% have mixed feelings. Moreover, only 13% agree or strongly agree suspensions make students less likely to misbehave in the future (see Figure 2). In fact, regardless of school context, few principals believe suspensions prevent future misbehavior.

Meanwhile, few principals (19%) believe that suspensions and expulsions for disruptive students can be justified by the fact that removing those students may improve the learning environment for their peers. And again, this was true across school contexts.

“Results from our nationally representative survey show that while public school principals believe that the primary purpose of discipline is to teach students appropriate skills, most do not believe suspensions and expulsions effectively serve this purpose.”

Despite not viewing suspensions and expulsions as achieving key goals, principals continue to see these forms of discipline as necessary tools.

Results from our nationally representative survey show that while public school principals believe that the primary purpose of discipline is to teach students appropriate skills, most do not believe suspensions and expulsions effectively serve this purpose. And yet, few principals in our study went so far as to say suspensions are entirely unnecessary. When we asked principals if they thought suspensions would be unnecessary if schools provide positive climates and challenging instructional environments, only 43% agreed.

So, we’re left with a puzzle: most principals don’t believe that suspensions and expulsions serve the purposes proponents claim they do, but many principals continue to use these practices—especially with students of color—and appear reluctant to give them up entirely. Why is that?

We can only offer a few hypotheses. First, zero-tolerance policies may limit principals’ options. It’s possible principals feel compelled by district policies to suspend students more often than they would like to do so. Second, as one former teacher points out, high-suspending schools may be insufficiently resourced to adopt non-punitive alternatives to suspensions. For example, effectively implementing a restorative justice program or restorative practices often requires significant school resources, including more time and engagement from teachers and counselors relative to exclusionary practices. Third, it could be that exclusionary practices remain prevalent simply because they are what educators are accustomed to. Reform efforts to limit exclusionary practices can represent a significant paradigm shift for some schools and educators—and this type of change can be frustratingly slow.

(For more details on the survey and the complete set of survey results, click here.)

Footnotes

- In addition to the questions about school discipline that we discuss in this post, our survey also included potentially sensitive questions about respondents’ racial attitudes. To ensure that individuals could not be identified in our survey data, we obtained only limited information about schools’ student demographics and contexts. Therefore, we report our results by school racial/ethnic composition using a categorical variable with three groups: “Mostly Black,” “Mostly White”, and “Neither” (where the “Neither” category represents schools that are neither majority Black nor majority white). Because “Mostly Black” schools represent a small share of U.S. public schools, we note that our sample sizes for this subgroup—at both the elementary and secondary levels—are smaller than for the other subgroups. Thus, we encourage readers to interpret these results with some caution. While we do not know the specific racial/ethnic breakdown among students in the schools categorized as “Neither,” we estimate this group is comprised of roughly half schools that are majority Latino and half schools in which none of these racial/ethnic groups comprise a majority based on patterns we observe among the national population of U.S. public schools. (Back to top)

Conflict of Interest Statement

Rachel M. Perera is an alumna of the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a past employee of the RAND corporation during which time she completed the majority of her contribution to this project. Perera remains an adjunct policy researcher with the RAND Corporation and received financial support from RAND to complete this project. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of the authors and do not represent positions or policies of the RAND Corporation, Brookings Institution, its officers, employees or other donors. Brookings is committed to quality, independence, and impact in all of its work.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support for this project from RAND’s sponsored research program; funding for this research was provided by gifts from RAND supporters and income from RAND operations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).