In 2016, nearly 1.7 million workers were directly involved in designing, constructing, operating, and governing U.S. water infrastructure. From water utilities, to specialty trade contractors, to heavy and civil engineering construction, these workers carry out specialized activities crucial to the long-term operation and maintenance of the country’s drinking water, wastewater, stormwater, and green infrastructure facilities. Read more about the report’s definitions for water workers on page 12.»

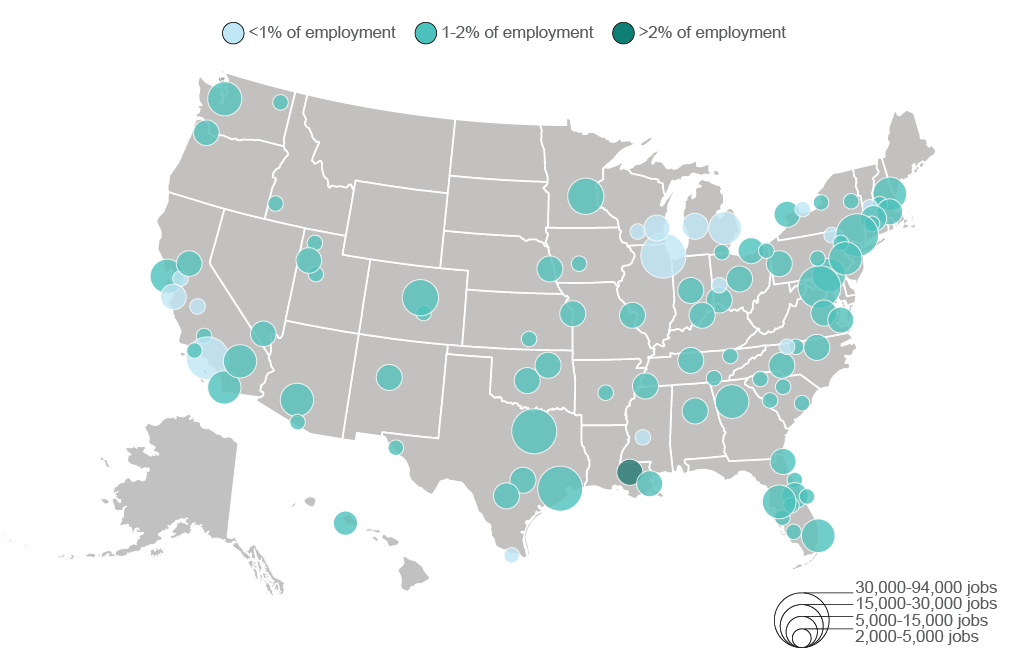

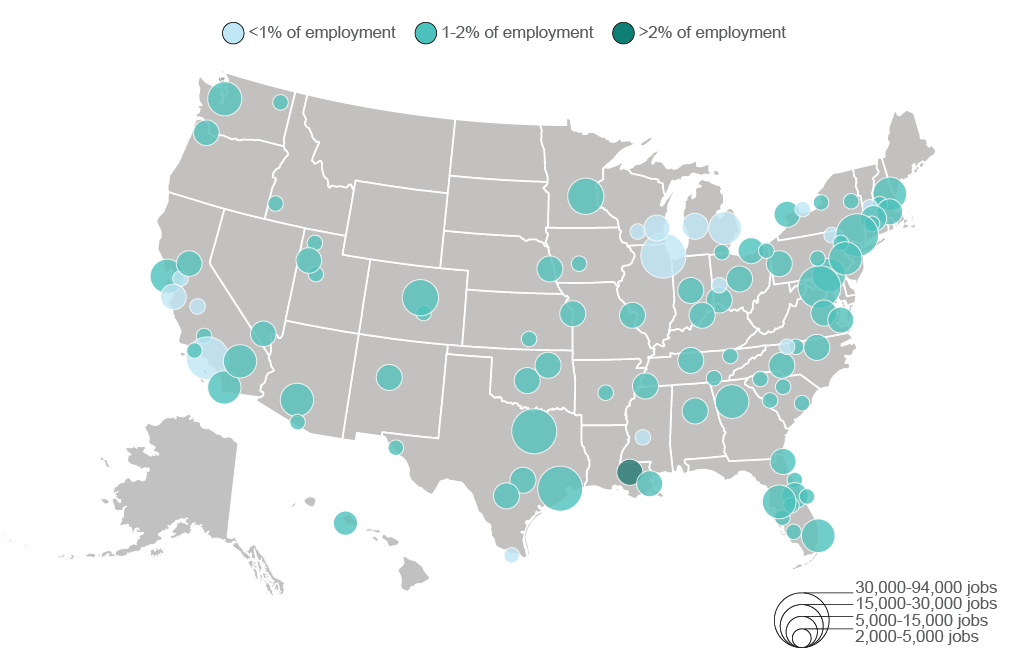

Employed across 212 different occupations, including plumbers, electricians, and instrument technicians, water workers embody many of the skilled trades. However, there are tens of thousands of other workers involved in administration, finance, and management roles. Perhaps most importantly, water workers are not isolated to only a few areas across the country, but are employed everywhere, speaking to their enormous geographic reach; they consistently represent 1 to 2 percent of total employment in the country’s metro areas and rural areas.

Water workers in the 100 largest metro areas

By total employment and share of employment, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics

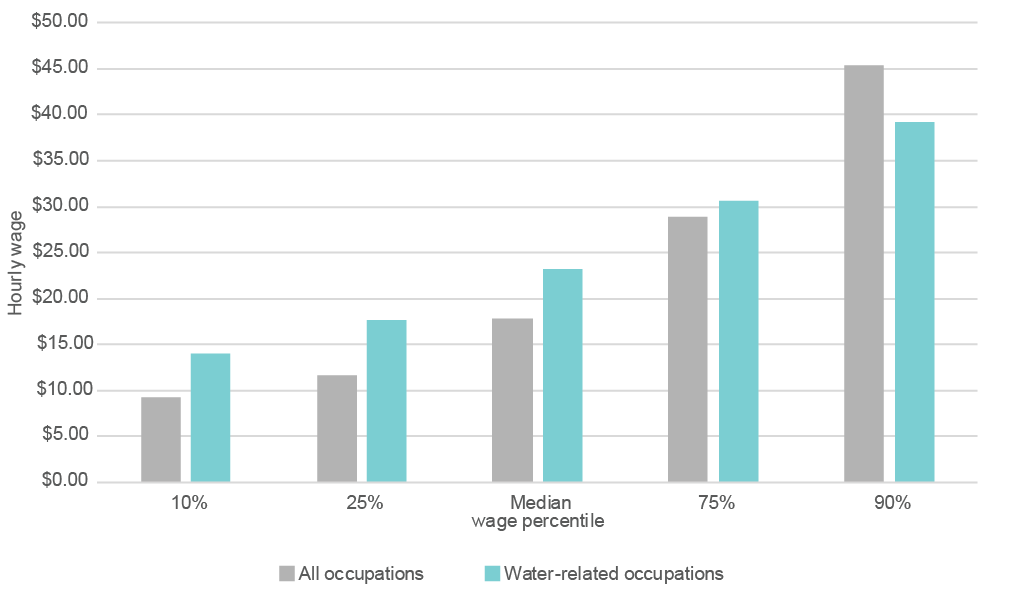

Water occupations pay well. Their average wage exceeds the national average, and their wage advantage is especially apparent at lower ends of the income scale. Water workers earn hourly wages of $14.01 and $17.67 at the 10th and 25th percentiles, respectively, compared to the hourly wages of $9.27 and $11.60 earned by all workers at these percentiles. These higher wages are also nearly ubiquitous across the water sector, with 180 of the 212 water occupations (or more than 1.5 million workers) earning higher wages at both of these percentiles. This means most water occupations earn a more livable wage in most places. Read more about wages in the water workforce on page 18.»

U.S. Hourly Wage Comparison: Water Occupations vs. All Occupations, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics

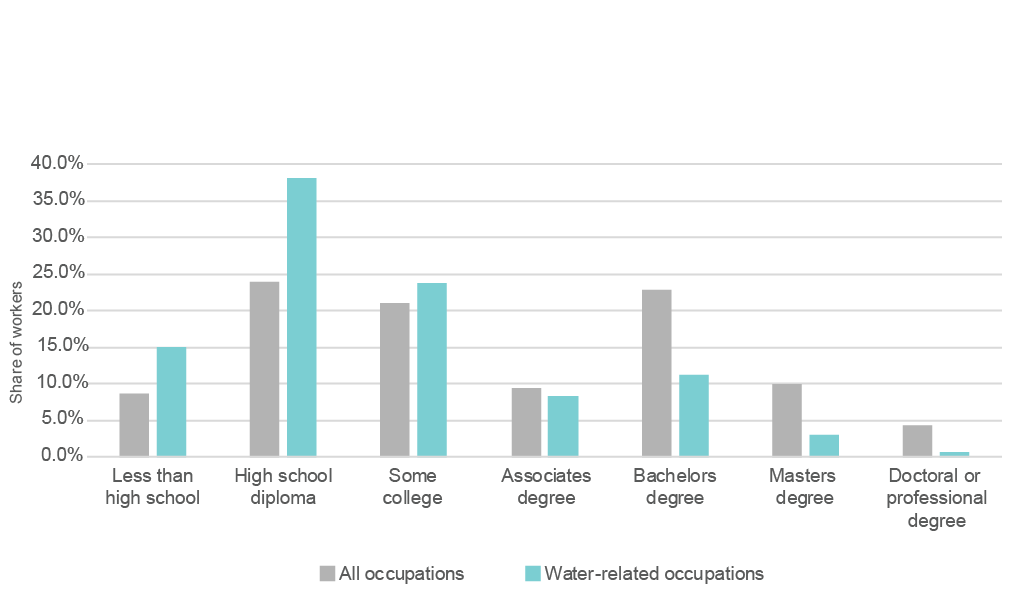

Even with higher pay, water occupations often do not demand much formal education. While 32.5 percent of workers across all occupations have a high school diploma or less, a majority of water workers (53 percent) fall into this category, including carpenters, welders, and septic tank servicers. Instead, water workers need extensive knowledge and skills developed on the job, underscoring the importance of applied learning opportunities. For example, 78.2 percent of water workers need at least one year of related work experience, and water treatment operators, plumbers, and HVAC technicians are among the many large occupations that require two to four years of related work experience. Read more about educational attainment, training requirements, and tools and technologies for water jobs on page 20.»

Educational Attainment for Workers in Water Occupations vs. All Occupations, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and Employment Projections data

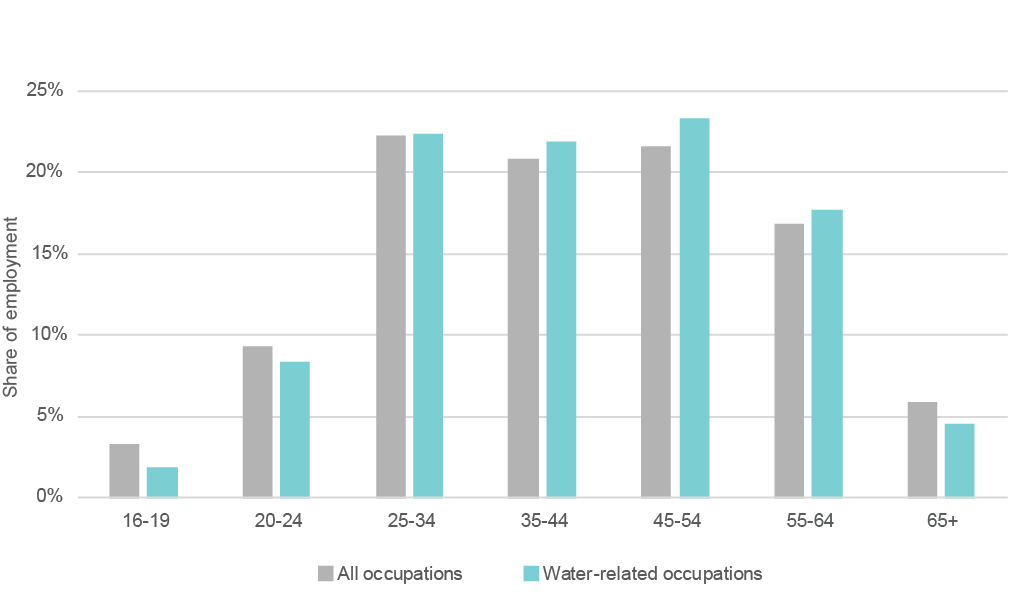

4Water workers tend to be older and lack gender and racial diversity in certain occupations, pointing to the need for younger, more diverse talent

Back to menu ↑ Next section →

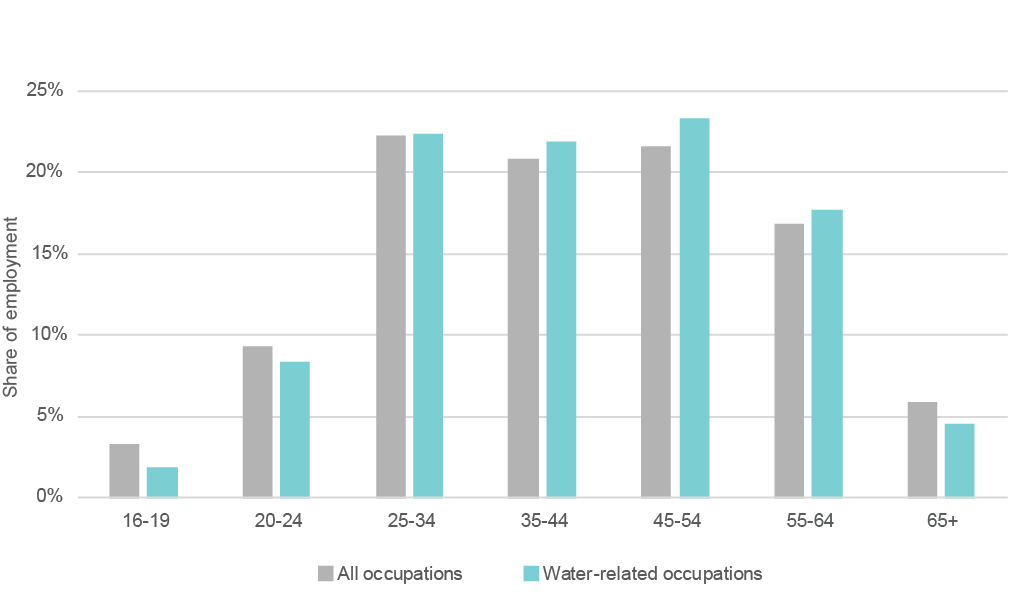

Thousands of water workers are aging and expected to retire from their positions in coming years, leading to a huge gap to fill for utilities and other water employers. Some water occupations are significantly older than the national median (42.2 years old), including water treatment operators (46.4 years old).

Age Range of Workers in Water Occupations vs. All Occupations, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and CPS data

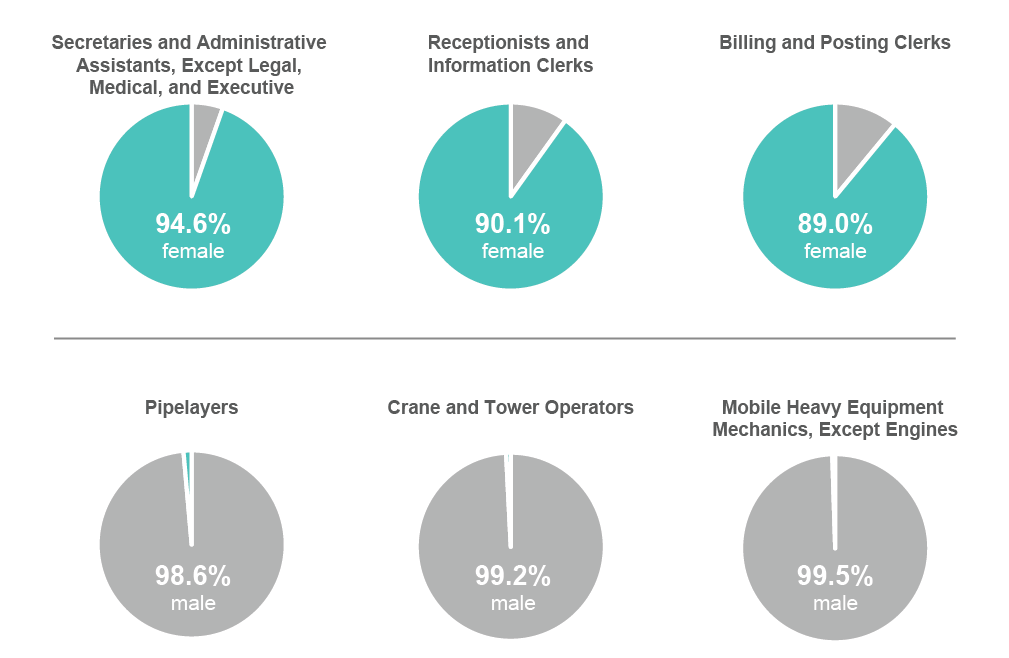

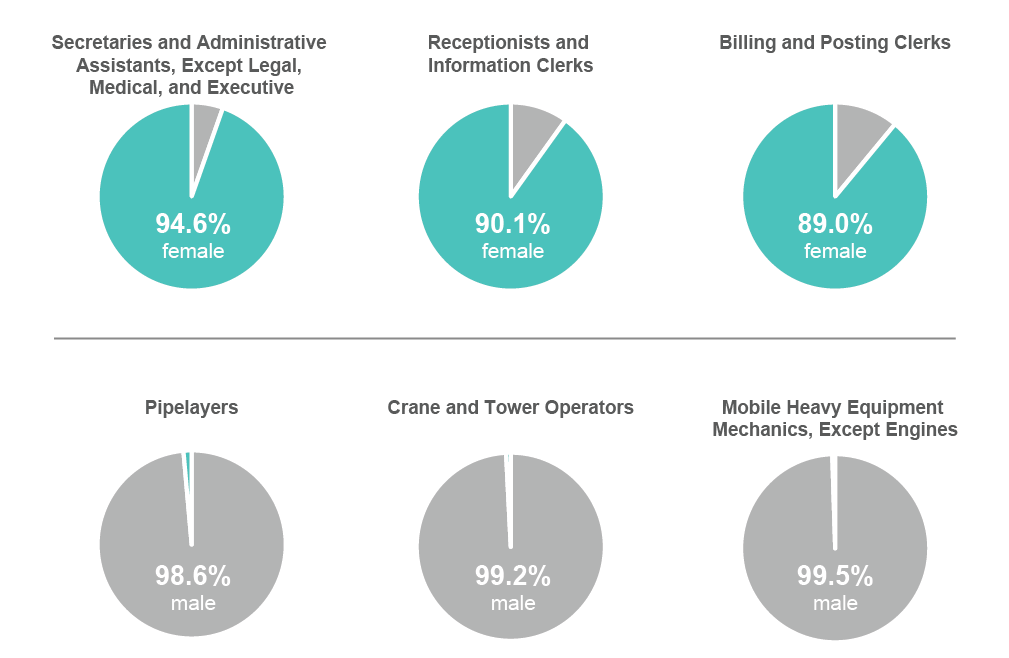

Water workers are predominantly male as well, particularly among positions in the skilled trades. Although women make up 46.8 percent of workers across all occupations nationally, they account for only 14.9 percent of the water workforce.

Selected Occupations with High and Low Shares of Female Workers, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and CPS data

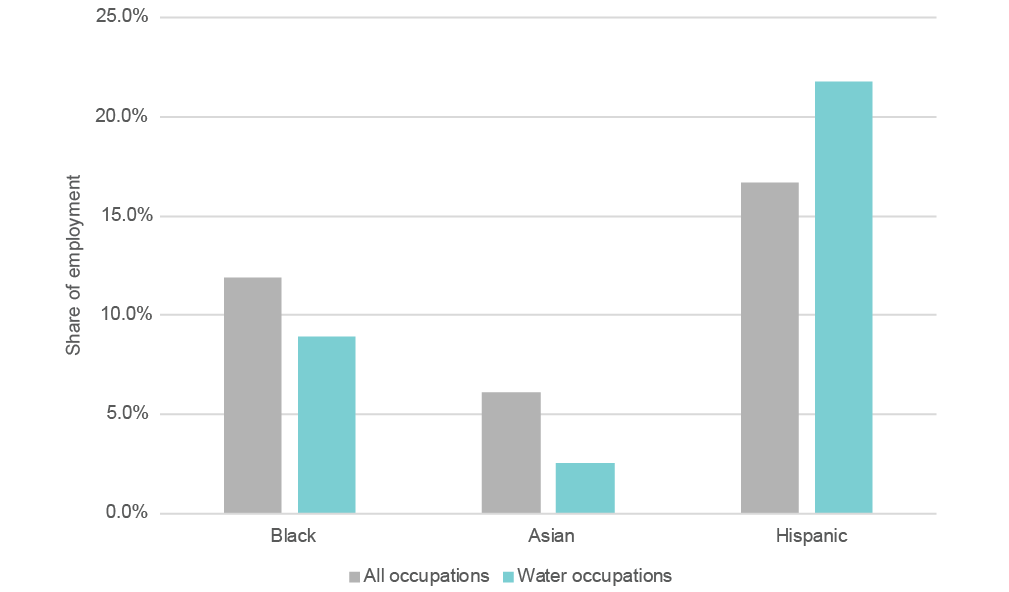

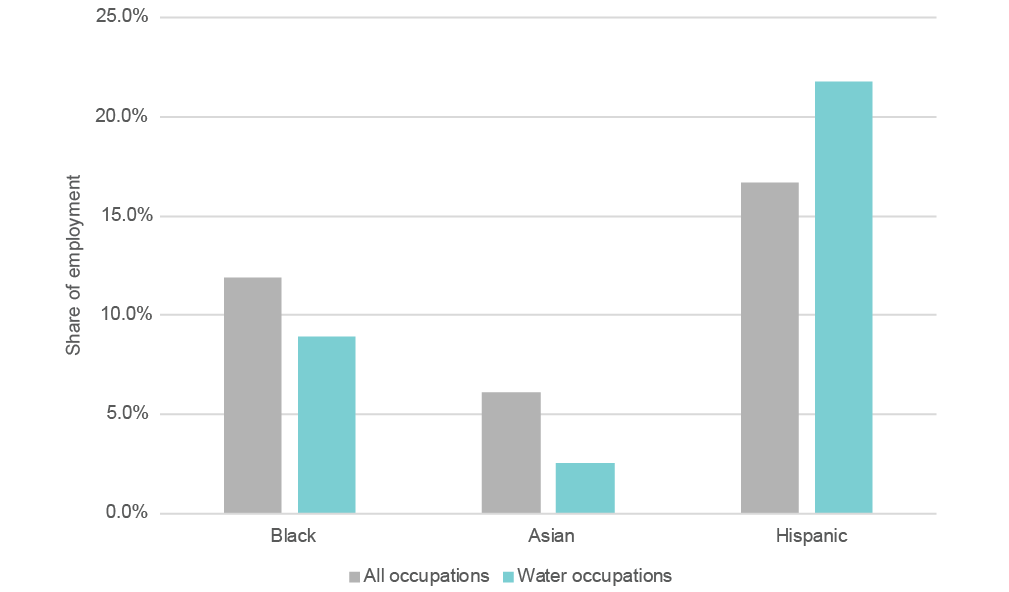

There is a notable lack of diversity in certain water occupations. While nearly two-thirds of the water workforce is white, similar to the ratio found across all occupations nationally (65.3 percent), black and Asian workers only make up 11.5 percent of the water workforce, compared to 18 percent of those employed in all occupations nationally. While the Hispanic share of the water workforce (21.8 percent) actually exceeds the national average across all occupations (16.7 percent), this is primarily due to their concentration in construction jobs. People of color, in particular, tend to be underrepresented in higher-level, higher-paying occupations involved in engineering or management. Read more about water workforce demographics on page 25.»

Racial Diversity in Water Occupations vs. All Occupations, 2016

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and CPS data

Together, water utilities, other water employers, community partners, and federal and state leaders have a long list of “to-do’s” to further elevate and expand the country’s water workforce opportunity. Not all places are equally equipped to accelerate their workforce development efforts, even if they have an appetite to test out new ideas. Read more about specific barriers to water workforce hiring, training, and retention on page 31.»

Ultimately, locally-driven actions are crucial to develop new strategies and target new investments, but the scale of the issue demands broader regional collaborations and national support to build additional financial, technical, and programmatic capacity. The country needs a water workforce playbook to accelerate thinking, action, and investment. Informed by site visits across three different regions (California’s Bay Area ; Louisville, Kentucky ; and Camden, New Jersey ), an expert roundtable in Washington, D.C., and multiple other conversations with industry leaders, this playbook calls for several actions:

1. Utilities and other water employers need to empower staff, adjust existing procedures, and pilot new efforts in support of the water workforce

2. A broad range of employers and community partners need to hold consistent dialogues, pool resources, and develop platforms focused on water workers

3. National and state leaders need to provide clearer technical guidance, more robust programmatic support, and targeted investments in water workforce development

1. Utilities and other water employers need to empower staff, adjust existing procedures, and pilot new efforts in support of the water workforce

- Hire and train dedicated staff to meet with younger students, connect with more diverse prospective workers, and explore alternative recruitment strategies

- Create a new branding strategy to more effectively market the utility or organization to younger students and a broader pool of prospective workers

- Account for workforce needs as part of the budget and capital planning process, while creating more detailed and consistent labor metrics

- Update or create new job categories to provide greater flexibility for potential applicants

- Develop competency models—or customize existing models—to promote continued learning and skills development among staff

- Design and launch new bridge programs, including “water bootcamps,” to provide ways for younger workers and other nontraditional workers to explore water careers and gain needed experience

- Implement a formalized mentorship program to provide interns and younger workers a clear point of contact and better monitor their career progression

2. A broad range of employers and community partners need to hold consistent dialogues, pool resources, and develop platforms focused on water workers

- Identify a common regional “point person”—or organization—to schedule and steward consistent meetings among a broad range of community partners

- Hold an annual water summit/meet-and-greet where prospective workers, employers, and community partners can connect with one another regionally

- Out of these dialogues, develop a comprehensive water workforce plan, highlighting regional training needs and avenues for additional collaboration

- Develop a more predictable, durable channel of funding to support these efforts, driven by public fees and private sector support

- Strengthen local hiring preferences in support of more minority and women business enterprises

- Create a new web platform to connect water workers and employers, serving as a simple, consolidated site for regional job postings

- Launch a new regional academy—designed and run by employers and community partners—in support of more portable infrastructure education, training, and credentials

3. National and state leaders need to provide clearer technical guidance, more robust programmatic support, and targeted investments in water workforce development

- Hire or assign specific program staff to serve as common points of contact across relevant federal agencies, with a focus on water workforce development

- Supported by federal agencies or other national organizations, conduct a series of dialogues and learning sessions in a broad range of markets to assess water workforce needs and priorities

- Develop a common landing page, or repository, that highlights regional best practices and other innovative water workforce development strategies

- At a national level, form a “water workforce council” among leading groups to serve as an advisory body, with an eye toward future priorities

- With guidance from employers, industry associations, and other stakeholders, establish more versatile and streamlined water certifications nationally

- Expand federal and state funding via existing workforce development programs and educational initiatives, including apprenticeships

- Expand federal and state funding via newly targeted and competitive grant programs, in support of alternative bridge programs and other innovative training programs

Read more about recommendations to revamp the water workforce on page 39.»

6Metro area data

This dashboard provides data on the water workforce in the country’s 100 largest metro areas, including employment totals, wages, and occupations. See the downloads section at the top of the page for additional data.

Back to menu ↑