This piece is part of a series titled “Nonstate armed actors and illicit economies: What the Biden administration needs to know,” from Brookings’s Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors.

As the international system experiences a multifaceted rearrangement of power distribution and modes of governance, challenges emanating from state actors like China and Russia are not the only issues to watch. Nonstate armed actors — militants, militias, and criminal groups — are acquiring increasing power at the expense of the state. This dynamic precedes the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, but has been exacerbated by it: More people around the world depend on illicit economies for basic livelihoods, and criminal and militant actors are empowered while governments are weakened. Unable to effectively confront nonstate armed actors, many governments will feel tempted or required to accommodate them, or attempt to coopt them. Governance by nonstate actors will deepen and expand.

As my Brookings colleagues and I address in more depth in a new series, these are key issues for the incoming Biden administration to watch.

COVID-19 and state-nonstate power dynamics

The pandemic is weakening the governing capacity of governments in multifaceted ways, amplifying deep-seated trends in progress for the past two decades. It wiped out 20 years of poverty reduction efforts, with as many as 150 million people pushed into extreme poverty. These numbers may significantly underestimate the calamity, as COVID-19 persists longer and more intensely than many thought, and vaccine distribution is proving more difficult than hoped, even in economically and institutionally-advanced countries.

Around the world, those affected by the illness, lockdowns, and economic collapse are forced to drastically limit their access to healthcare, food, schooling. Many have to liquidate their means of human capital development. In one study conducted in Kenya, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), over 75% of women reported at least a partial loss of household income and food insecurity, with 62% of the surveyed households in the Kinhasa province of DRC reporting a total loss of income! Latin America has likewise seen devastating economic effects, with GDP losses already at some 10%. Economies in Africa have been hit equally hard, as have many economies in Asia, and particularly the conditions of the vulnerable.

This severely constrains budgets for public expenditures, including public safety budgets. A rise in crime and conflict, along with governments’ inability to sufficiently offset the economic devastation and destruction of people’s livelihoods, profoundly weakens the legitimacy of governments and political systems. Political instability and social strife, including violent protests and extremist mobilization, are likely to increase in many parts of the world, even as the extent of government weakness will vary.

So are authoritarian power grabs — not necessarily through outright coup d’etats, but under the guise of anti-crime measures. See, for instance, the Philippines, or the incremental weakening of accountability mechanisms and institutional capacity and delay of elections in Malaysia and Ethiopia. Authoritarian governments, for example in Hungary, have used the pandemic as an excuse to expand executive authority and squash opposition.

Concurrently, criminal and militant groups, as well as other nonstate armed actors, have become relatively stronger. More people now depend on illicit economies for basic livelihoods, and on criminal or militant groups for basic services. The political capital of nonstate armed actors, particularly those sponsoring labor-intensive illicit economies or access to jobs in legal or informal economies, has grown. Larger territorial spaces, functional domains, and populations will be governed by nonstate actors, something that will outlast the pandemic.

Assuring access to vaccines for the most marginalized populations will necessitate negotiating with nonstate armed actors, some of which may ask for political or material payoffs. But however problematic such negotiations are, laws against material support to nonstate armed actors should not hold back vaccinations and humanitarian relief — for reasons of global public health, economic recovery, and basic justice. Care needs to be taken to minimize the resulting political power of nonstate armed actors that accrues through such negotiations.

Militant groups around the world — including al-Shabab, the Taliban, and the Islamic State in West Africa Province, various nonstate armed actors in Colombia, and the Houthis in Yemen — have sought to exploit COVID-19. So have various criminal groups — mafia groups in Italy; Mexican drug trafficking organizations; gangs in Central America; and the slums of India, Kenya, or Brazil. The ways they have exploited COVID-19 varies: Some have reshaped anti-government and anti-Western propaganda, increased recruitments, intensified violence, provided socio-economic handouts and other public goods, or taken over bankrupt businesses and penetrated the legal economy. Not all nonstate armed actors are equally adroit in exploiting the pandemic, but they have used it to tighten control over local populations in a variety of ways.

The developed world has not escaped these pernicious dynamics, with new economic hardships and lockdowns boosting preexisting trends in right-wing violent mobilization. In the United States and Western Europe, right-wing armed groups — the Boogaloo Bois, neo-Nazi groups, and anti-federal government groups that espouse so-called County Supremacy — have exploited the pandemic to build political capital with disgruntled business owners, increased recruitment, targeted and intimidated law enforcement, and sought to both discredit and coopt political representatives. They have intensified networking and sharing of tactics with counterparts elsewhere in the world. They represent severe threats to rule of law and safety in the West, as was demonstrated in the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The pandemic’s fallout will last years, as will the dependence of many in the world on illicit economies. So too will the increased power of nonstate armed actors. Even in the West, the mobilization, recruitment, and political capital of armed groups and societal polarization will not rapidly disappear.

Government responses

Yet many policies that governments may be tempted to adopt — including increasing repressive tools against protesters and nonstate armed actors — exacerbate the problems. In some localities, governments are simply relegating or yielding control to criminal groups and other nonstate armed actors — long the case in Brazil, Jamaica, Central America, Bangladesh, and India, but now more prevalent. Elsewhere, they negotiate with and coopt nonstate armed groups to extort or coopt votes, obtain funding, settle scores with political or business rivals, or take on other nonstate armed actors.

Moreover, dangerous and counterproductive natural resource extraction — logging, mining, and wildlife trade and trafficking — is likely to intensify, and can be illegal or legal. Wildlife poaching has exploded worldwide, including in previously well-protected areas, as incomes for rangers and local populations dry up and some people migrate from cities to rural areas. Wildlife-based Traditional Chinese Medicine continues to be, without proof, promoted as COVID-19 cures. Deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia, meanwhile, broke records in 2020. In Asia, Latin America, and Africa, economies in natural resources will be the most available source of revenues for governments, and livelihoods for many.

But their extraction, and the resulting degradation and increased trade in wildlife, may speed up the arrival of another zoonotic pandemic. China, in particular, remains a problematic actor: Its imports of beef, soy, and timber are significant sources of deforestation. The modus operandi of China, Russia, and also India in resource extraction in Africa, Asia, and Latin America has fueled corruption, and weakened rule-of-law and good governance. COVID-19 has diminished governments’ capacities to resist such deleterious practices and avoid debt traps. Conditioned, monitored, and sequenced debt relief for habitat and biodiversity preservation is an important countermeasure.

Geopolitics and nonstate armed actors

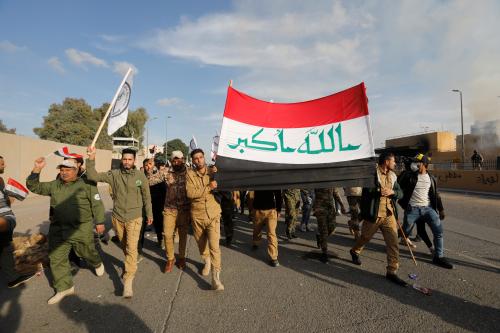

Some states — for instance Iran, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar will seek to exploit this instability via proxy proxy actors. In the Middle East and Africa, Russia has already inserted proxy actors (such as the Wagner Group) and security advisers into various unstable or conflict-ridden countries; Russia may also seek to exacerbate instability even without cultivating a particular local political proxy, as it did during the 2019 social protests in Latin America. But with its readiness to embrace and deploy nonstate armed actors for hybrid warfare and asymmetric purposes, Russia may also cultivate criminal groups and other nonstate armed actors to undermine U.S. partners, like in Ukraine.

China, so far, has mostly made accommodations with nonstate armed actors in Myanmar and Afghanistan. In Myanmar, it has cultivated strong relations with a set of ethnic militias and sometimes even their rivals, while maintaining strong influence over the government even under Aung San Suu Kyi. Chinese actors, including state ones, participate in illicit economies in Myanmar and around the world, particularly in wildlife and timber, but sometimes also drugs. In Afghanistan, China prefers a coalition government to emerge and constrain the Taliban, but it has worked out a détente with the group. China does not as yet have a known record of cultivating criminal groups and proxy militias for geopolitical purposes far away from its borders, but that time may come.

China is far more likely to seek to cultivate governments — such as by selling them anti-crime software (like Smart and Safe Cities), which China extensively promotes in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. To governments with tight budgets and ineffective law enforcement, that face violent crime and powerful criminal groups, such technologies may seem like silver bullets. But they can serve as backdoors for China to engage in spying and industrial espionage. Governments can also exploit them for authoritarian purposes.

In a perpetual cat-and-mouse game with states, nonstate armed actors too have long embraced advanced technologies for nefarious purposes — including, lately, drones for reconnaissance, smuggling, and armed warfare; semi-submersibles for long-distance maritime smuggling; closed-circuit TVs for population control; cryptocurrencies for money laundering; synthetic drugs for enrichment; and a variety of cybercrime and cyber tools to create mayhem, inflict pain, steal money, and extort. In some cases, the COVID-19 disruptions to legal trade have forced criminal groups to accelerate their expansion into these high-tech and cutting-edge domains, such as the use of drones for drug trafficking and retail, and other innovations.

What this means for policy

The return to geopolitical competition does not negate the growing influence of nonstate armed actors. Nor should geopolitical competition obscure the focus of U.S. national security and foreign policy on nonstate armed actors. COVID-19 has significantly amplified the power and impact of such actors around the world. Geopolitics has added complicated layers to their role and power, in some ways entrenching them further.

This new power landscape also raises important questions about the tools the United States has deployed to counter nonstate armed actors. The post-9/11 reliance on direct U.S. military intervention may be over, even if the U.S. proclivity to stand up proxy militias persists.

This new shape of the power and reach of nonstate armed actors reinforces the imperative for the United States to review its response, including vis-à-vis rival powers. Key issues the Biden administration will need to address include:

- Which types of nonstate armed actors, under what circumstances, should be countered —and with what types of military power — to minimize the violence they can inflict on the United States, allies and partners, and local populations, while avoiding counterproductive side effects;

- How to improve and intensify law enforcement operations against nonstate armed actors, including in the United States, such as through operations and prosecution, while preserving civil liberties, as well as diffuse their overall threat by reducing recruitment and disrupting organizational capacities;

- How to better limit the counterproductive and destabilizing effects of the militia groups the United States supports, and eventually wind them down and integrate them;

- How to enhance the effectiveness of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration processes for nonstate armed actors;

- When and how to use specific non-military tools — such as socio-economic measures and foreign assistance focused on strengthening governance — to create stronger bonds between people and governments, mitigate mis-governance, and wean local populations off dependence on illegal economies and nonstate armed actors;

- How to encourage politicians, political systems, and governments to stop using nonstate armed actors for their purposes;

- How to work with allies and partners to counter nonstate armed actors, without reinforcing authoritarian tendencies and other bad governance that give nonstate armed actors the capacity to entrench themselves;

- When and how to negotiate with nonstate armed actors, including criminal groups; and

- Most controversially, but also very importantly, how to shape nonstate armed actors to advance U.S. interests and separate them from U.S. geopolitical rivals — without losing sight of promoting greater accountability and inclusiveness in the behavior of nonstate armed actors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The key trends to watch this year on nonstate armed actors

January 15, 2021