This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

Nothing in this article relates to the COVID-19 pandemic. Why? It’s not because new federal agency rules won’t be part of the solution. It’s because this article is about improving the notice-and-comment rulemaking process whereas, in emergencies like this, federal agencies are empowered to issue emergency regulations that by-pass the usual prior notice and public comment process, yet still have the force of law. Specifically, where agencies find “good cause” deem the normal waiting period and public comment to be “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest,” they are empowered to regulate directly, effective immediately.

Courts employ a balancing test to decide whether this narrow exception is available. Anyone who’s looked at the impact of government interventions on morbidity and mortality projections thirty or ninety days out knows immediately where that balance must be struck: hundreds of thousands of lives are at stake! The Families First Coronavirus Response Act directs agencies to issue a number of “good cause” regulations, but agencies are free under the circumstances to find good cause for other actions on their own. In normal times, agencies haven’t been shy about using “good cause” to launch end runs around the notice and comment process, particularly when their litigation risk is low. In the case of COVID, unilateral, immediate agency action is a cornerstone of the new normal.

For those of us who aren’t yet sick ourselves, or directly involved in the care of those who are, Week Three of working from home may be a time to consider how the post-pandemic world might be improved. Here are some thoughts about how public participation in normal notice-and-comment agency rulemaking can be improved.

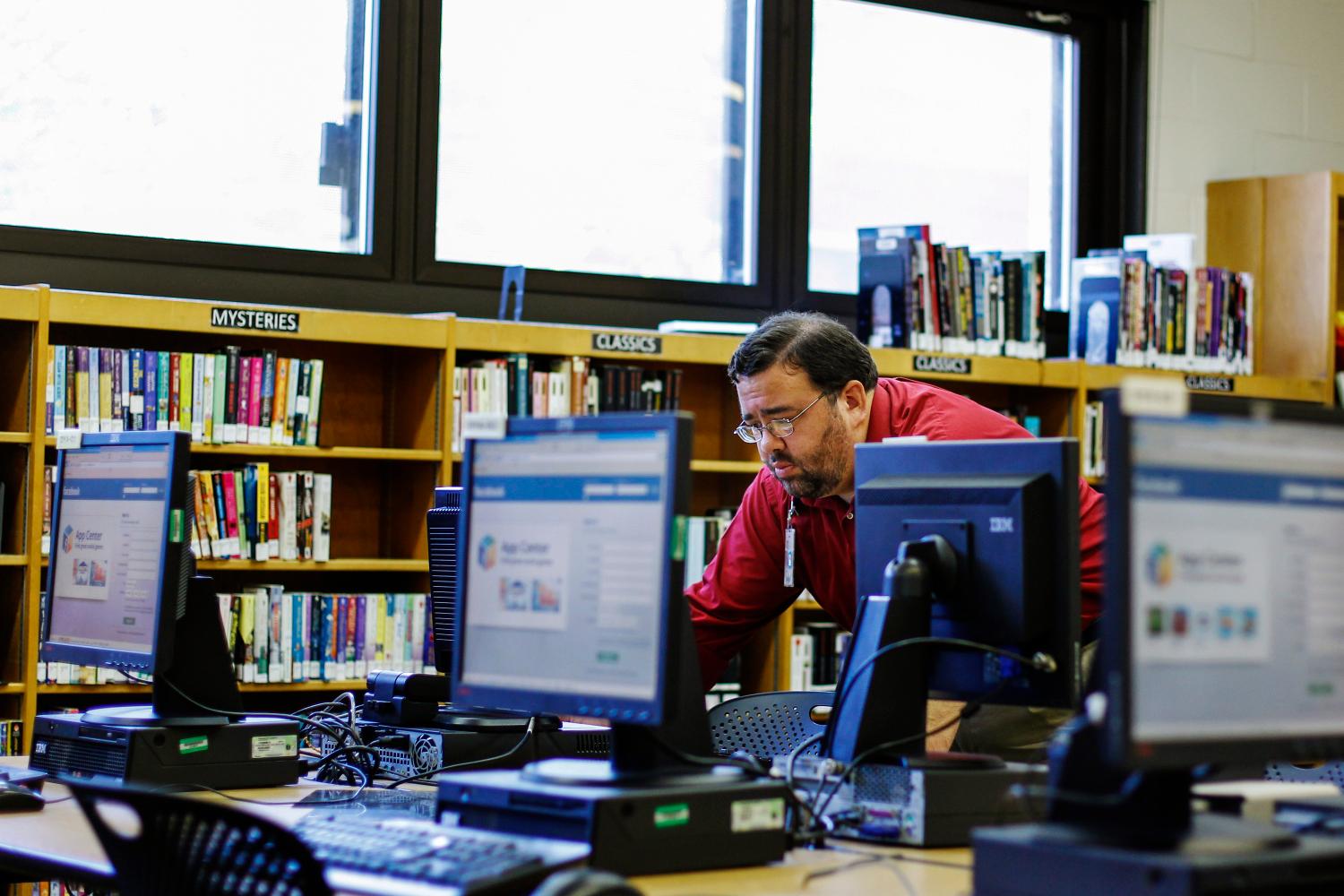

Before the Internet, someone seeking to comment on a proposed rule would mail a paper letter to the relevant federal agency. Such a commenter could only see comments from others by going into the agency’s office and viewing the hard copies—a steep hurdle. While the advent of e-rulemaking has improved the situation, much more could be done to make rulemaking more interactive and inclusive.

The latest proposal to further this goal comes from the General Services Administration, which recently became a managing partner of the federal e-rulemaking program. The proposal asks the public for feedback on a number of questions, including how to improve Regulations.gov, the portal that most federal agencies use to receive public comments on proposed rules.

In our view, the GSA reform initiative presents an opportunity to build a notice-and-comment process that is more deliberative and delivers higher quality feedback to the agency. The ideal, at least for rules that spark public interest, would be for the agency comment file to become a temporary community with its own dynamics that encourages deliberation and even self-correcting. Encouraging interaction between commenters would improve the dynamics of commenting, possibly helping to generate consensus and put the real issues into focus. More broadly, the goal of our proposal is to encourage public participation, which would make notice-and-comment rulemaking more democratic and perhaps less slanted in favor of professional commenters with major knowledge and resource advantages.

This is no easy task. Agencies currently contend with an overwhelming volume of electronic comments—many of them duplicative, and some of them totally fake. But some other websites have done better in encouraging informed dialogue among commenters. Can the same happen for public comments on rules? Is there a simple fix for the notice-and-comment process? Can we respect the public’s right to make comments anonymously but also incentivize accountable self-identification?

Upvoting: A Way to Make Rulemaking Commenting More Interactive

The first step is to stop treating electronic comments like snail mail letters and make rulemaking more interactive. The happy result would bring us closer to the deliberative “national town meeting” than the framers of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) could have dreamt possible in the 1940s. The APA’s framework for public participation has always contemplated oral presentations. But in practice, the process quickly became a one-way street, with bags of snail mail from the public dumped on the agency’s doorstep. At a town hall meeting, by contrast, everyone who attends is listening to what you have to say, not just the officials in the front of the room. One comment might be greeted with murmurs of approval, while another might encounter jeers and sneers. Isn’t that a better model for electronic commenting?

To that end, we propose to allow commenters to “upvote” and “downvote” other people’s comments. For each rule, the Regulations.gov website would display the vote totals and display the most popular comments first. Commenters whose point has already been made well might content themselves with giving the most cogent comments a thumbs-up. A commenter with something new to add could limit her submission to that incremental point. We hope that hundreds and thousands of similar or identical comments would be replaced with a round of electronic applause.

Upvoting could encourage more people to participate in the rulemaking process. Users engage more with platforms that provide feedback on their submissions (examples include Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, which enable users to “like” and “comment” on posts). This desire for positive feedback could induce more people to submit accessible and compelling comments, at least at the margins (we recognize that Regulations.gov will never be as compelling for most people as a visual platform like Instagram).

Upvoting might also encourage more genuine deliberation between commenters. Given the polarization of United States politics generally, and the professionalization of much of the comment process, this may seem unlikely. But, it would be encouraging to find individuals agreeing with comments on both sides of an issue: it would signal a genuinely hard issue, where both sides have a point.

Our hope is that all this would have the effect of improving the quality and reducing the number of comments from the general public. The professional commenter community would probably like it, too, because it gives them more work. We think professional commenters would probably put comments in both early and late, hoping to get their early comments upvoted, and also arrange to upvote the comments agreeing with their position. And we think all that is fair game, and good information—at least once a certification mechanism is in place to prevent outright manipulation (more on this below).

Successful upvoting may also give agencies feedback on which issues incite strong public views. Today, form letters partially serve this function. Rulemaking is not a plebiscite, but comment form letters can signal to the agency public interest in an issue. But form letters are archaic and we can do better in 2020. A million “likes” of one comment makes more sense than the current situation, with a million identical comments on some rules. Reducing duplicative comments will also help the public work through the comment file more quickly. Lastly, it may help the agency work through comments more quickly, although software programs and contractors already do much of this work on the back-end.

Rules for Upvoting

Upvoting requires rules and oversight to work well. For policy and perhaps Constitutional reasons, agencies should continue to allow both anonymous and pseudonymous comments. These categories should be tallied separately, so that the agency and the public can count them for what they’re worth. Agencies should also give commenters the option to sign in as Certified Commenters, if they so choose. Certified Commenters would have to give their real names, which would be posted on the site, and their snail mail and email addresses, which would not be posted. They would certify that that their personal information is genuine, and that they believe in good faith that the facts they are asserting are true. They could also be required to disclose relevant affiliations with organized corporate and public interest groups. Agencies should remind certified commenters that intentionally providing false information (as opposed to a good faith error) is subject to prosecution as a felony for making a false statement to the government. The threat that a news reporter or advocacy group would expose such a false statement may be enough to deter many would-be fraudulent registrations, particularly since news coverage could attract the interest of the FBI and DOJ.

We thought about allowing only Certified Commenters to up- or down-vote other people’s comments, or to take part in the Reply threads. But perhaps we can incentivize certification by less radical means: simply do not count uncertified comments towards promoting comments as popular. And break down the vote count as, say, 35 certified likes, 2000 uncertified likes, 200 certified “thumbs down” and 20 uncertified “thumbs down.” We would also put uncertified comments into a different font and color, as a reminder to the Agency and other readers of the file that there’s a heightened possibility they may not reflect genuine input. Together, these rules would create a soft incentive to register.

To prevent manipulation, each individual Certified Commenter should be limited to one upvote per comment. This limit will make the upvote more meaningful while preventing individuals from distorting the process by casting many upvotes. Both the agency and the public should be able to click on a certified commenter’s name and see all of their comments, first on the rule at issue, and then, on all the others. And, importantly, users should be able to do the same for pseudonymous commenters. There should therefore be a strict rule of one-pseudonym-per-commenter. This is the keystone of the rules that make Wikipedia function as well as it does. Bad actors can be tracked and dealt with by their peers, because all their (pseudonymous) Wikipedia work is visible to the rest of the community.

What Else Do We Need to Make Upvoting Work?

Using existing agency tools, commenters can now read all previous comments. However, this has serious challenges. Some rules receive many long and complicated comments, requiring a significant time to work through. To reduce this burden, commenters should be able to do a full-text search of all previous comments, to help them see quickly if their points have been made before. Commenters should also be able to cross-reference the comments of others via hyperlink. These tools will make it more feasible for people to make sense of what other commenters have said.

Agency comment websites should also enable and encourage direct replies to comments, and replies to replies. It would be great if, when Commenter A puts in a false or misleading “fact,” a reply could correct it right then and there, citing reliable sources. Lines of argument channeled into on-topic threads would make for a more focused and coherent debate.

Rule-writers should generally resist the temptation to reply to commenters in real time during the comment period itself. Since the agency has both the first and the last word, it seems a bit much to intrude on the middle ground as well. Doing so would also consume limited agency resources. Still, judicious factual corrections (“The issue that troubles you is in the statute; a mere regulation can’t do anything about this”) might be permissible and salutary, if used sparingly.

The upvoting system could be undermined if overwhelmed by comments from bots that attempt to replicate human comments. Technology to sniff out such bots will be essential to maintaining the integrity of the upvoting system. This need not be costly, as agencies could use a free filter system such as Google’s ReCAPTCHA. None of this is to deter mass participation. If the auto dealer lobby (to take one example) gets a bunch of auto dealers to “like” their comment on some rule, then the process is working as intended.

Conclusions

The current e-rulemaking system leaves much room for improvement. Thoughtfully designed prior attempts at making the system more accessible and more deliberative have not taken off. Thus, it is time to try something new. Still, we know that some will object.

Our objective is to enhance the amount and quality of deliberation by adopting technology that has done so in other contexts.

One potential objection to counting upvotes is that it would change rulemaking from a process in which ideas are presented and debated into a plebiscite over the rule. This is not our objective, and we appreciate that rulemaking is a deliberative rather than aggregative process. Instead, our objective is to enhance the amount and quality of deliberation by adopting technology that has done so in other contexts. Moreover, our research is consistent with those who argue in favor of agencies gleaning as much feedback as possible from mass comments.

A second potential objection is that upvoting can be influenced by path-dependency. Because the most popular comments appear first, they often attract more votes, which can keeps them on top. This problem is real but limited by the fact that a well-done comment could always take off. In any case, we think the benefits of upvoting outweigh this risk.

A final possible objection is that excessive focus on engagement metrics can lead to low-quality content dominating the Internet. But this is less of a concern in the rulemaking context. The agency sets the contours of the debate and decides what matters. There is no reward such as advertising dollars for getting more clicks. Thus, the worry about click-bait is reduced.

On balance, any potential downside risk is limited. Agencies would not be not bound by anything that would come out of upvoting. Indeed, their current obligations under the APA to weigh all evidence and to explain their decisions would remain. Unlike some other proposals aimed at a similar goal, our proposal does not require the agency to spend resources to engage with individuals who may comment. It does not require the agency to do outreach. These are real deterrents to encouraging agency participation.

Rulemaking has long been skewed in favor of the sophisticated and well resourced. Upvoting is one small effort to make it a little less so.

The authors did not receive any financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

The SEC disclaims responsibility for any private publication or statement of any SEC employee or Commissioner. The article expresses the authors’ views and does not necessarily reflect those of the Commission or other members of the staff.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).