We are in the middle of a presidential transition, a quadrennial process that is vastly more interesting when there is a new president and even more interesting when the new president is from a different political party. That’s because, as the inside-the-beltway saying goes, “personnel is policy.” That adage is especially apropos for President-elect Trump whose campaign was long on tweets and short on policy papers.

The core of any transition is filling what the government calls “non-competitive” positions. Only the federal government could come up with a term that has so little to do with reality. These “non-competitive positions” are, in fact, quite competitive. The competition for Cabinet positions and White House staff positions can get red hot. But they are called “non-competitive” because no one is required to take a civil service exam or to abide by civil service rules in the hiring process. These appointees serve at the pleasure of the President and his people.

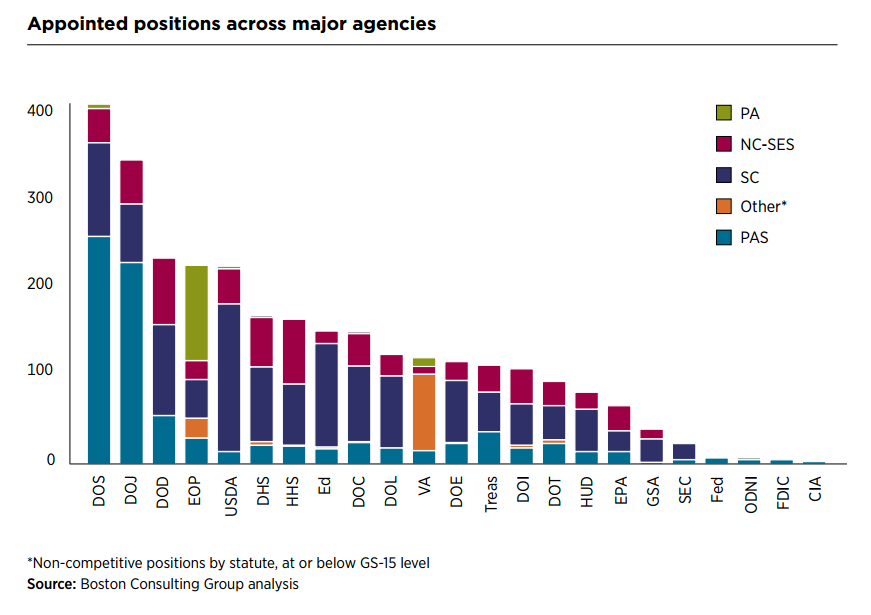

The following figure comes from the “Presidential Transition Guide” published by the Partnership for Public Service—the authority when it comes to federal government workers. All in all the president has 4,115 people who serve at his discretion. Of course he doesn’t actually appoint every single one of them. The important ones are called PAS, short for Presidential Appointment with Senate Confirmation. This number however, as Paul R. Lawrence and Mark A. Abramson point out in their must-read book “Succeeding as a Political Executive” is misleading because “…it includes part-time positions to presidentially appointed boards and commissions. A more commonly accepted figure is that there are between 700 and 800 executive-level positions to be filled.” Figure 1 shows the breakdown of presidential appointments. It may seem like a lot but these 4,115 positions (some of which are support positions only) are but a small fraction of the 4,185,000 people who work for the federal government and who are not hired and cannot be fired by the President.

Figure 1

The next figure, also from the Partnership for Public Service, shows the distribution of these different kinds of presidential appointees across the various agencies. The EOP (Executive Office of the President) mainly houses the White House staff and thus contains the largest number of presidential appointees who do not have to be confirmed by the Senate. This is where powerful actors close to the president who might have confirmation problems often end up. Think Steve Bannon, the controversial chief strategist whose background at Breitbart News has raised questions, or Mike Flynn—a controversial former General and activist—both of whom have landed important jobs that do not require Senate confirmation.

Figure 2

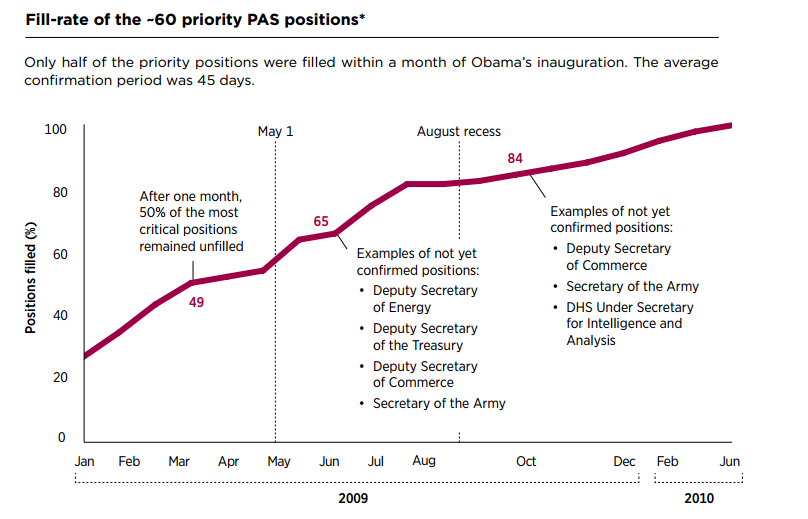

Putting together a government is a lot of work. And even successful transitions only manage to get a small amount of it done. This means that, in reality, the transition from one president to another goes on for most of the first year in office. The following chart, also from the Partnership for Public Service, shows that the 2009 Obama Administration (the last transition with a party change) filled jobs very slowly. By the summer of 2009 there were many important jobs that were still not filled. And remember, Obama had a solid Democratic Congress in his first two years, and Trump will have a solid Republican Congress for the first two years.

Figure 3

While the Trump Cabinet is shaping up on or ahead of schedule, he is slow in filling out his White House staff and Politico reports that Trump’s agency review teams are slow to visit the various government offices and get briefed on the handover.

Elaine C. Kamarck is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Why Presidents Fail And How They Can Succeed Again. She is a superdelegate to the Democratic convention.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Everything you need to know about a presidential transition in three easy charts

December 12, 2016