This November marked the annual Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week—aptly timed to coincide with the season of giving, celebrations of harvest plenty, and, in much of the country, the arrival of the cold, cruel weather that makes homelessness perhaps ever so slightly more in the conscience of those who don’t personally have to worry about it.

This might be particularly true this year, given the “devastating” recent national surge in people experiencing homelessness who are occupying public spaces (also known as “unsheltered”). As downtowns struggle to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, the “tent cities” and “encampments” that have filled spaces once busy with office workers have become tangible symbols of the virus’s crushing effects. Americans and foreign visitors alike have been shocked by the scale of unsheltered homelessness in our cities, and the limits of our current structures of governance—at all scales—to solve it.

Given the fractured nature of the American landscape, we shouldn’t be so surprised. While the roots of—and ideally the remedies for—homelessness are expansive across both systems (e.g., health care, housing, workforce) and geography, the visibility of—and hence the unspoken responsibility for—unsheltered individuals is largely confined to the parks and plazas where they congregate and the organizations that manage those spaces. This mismatch perfectly illustrates the perils of the country’s entrenched patterns of segregation—and why reimagining governance is key to dismantling it.

Segregation has blinded many Americans to the homelessness crisis

In the nearly seven decades since the Brown v. Board of Education decision struck down the farcical notion that Black and white Americans could be “separate but equal” in the eyes of law and society, segregation in the U.S. has increased in spatial scale and expanded to include separation by income and land use type. Thus, even as the country has become more racially diverse, it is still mostly segregated by race at the neighborhood level, and even as overall poverty declined, concentrated poverty has gotten worse. Meanwhile, different land uses such as houses, apartments, stores, and offices are farther apart than ever.

This segregation inevitably produces unequal outcomes and has helped create the ongoing homelessness crisis. Wealth and opportunity are hoarded in some neighborhoods while poverty is concentrated in others. Between neighborhoods, low wages and high costs produce a shortage of affordable housing, while inadequate social systems—including unemployment insurance, mental health treatment, and the criminal justice system—let many people fall through the cracks. But across the huge land areas required to segregate a growing population by race, income, and land use, most people are safely distant from having to actually see any manifestation of this inequality, much less feel accountability for it.

Simply put, the near invisibility of the unsheltered for many Americans is due to the fact that not every place sees homelessness to the same degree. Because people experiencing homelessness are drawn to the most highly accessible locations to meet their needs (to public spaces where they retain some rights and to visible hubs that may provide some sense of security), most places have no homeless people and a few have a lot. The upshot of these distributional issues is that there is tremendous pressure on only a small number of people and places to “solve” homelessness, even when the causes are systemic.

This status quo is not inevitable and does not have to remain permanent. As Brookings’s Hanna Love and Jennifer S. Vey note, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the limits of quarantine, isolation, and separation policies painfully obvious. Instead, we need to reform, invest in, and break down silos between federal, state, and local governance systems—from housing to health care—that can help prevent homelessness. But we also need to evolve a new generation of hyperlocal place governance organizations that are often already working in the spaces and communities where people experiencing homelessness gather—and who can more intimately see, understand, and help respond to the crisis.

Place governance is key to addressing homelessness

Historians and sociologists have long noted that the end of state-enforced de jure segregation in the civil rights era was replaced by a new reality of de facto segregation enforced by privatization and markets. This privatization includes entire geographic areas smaller than any public general purpose government (such as a county or most municipalities). Neighborhoods and places are increasingly governed by structures like private homeowners associations, quasi-private business improvement districts (BIDs), or even technically public suburban micro-municipalities created through defensive incorporation—places like Highland Park, Texas (which is completely surrounded by Dallas) or Beverly Hills, Calif. (surrounded by Los Angeles).

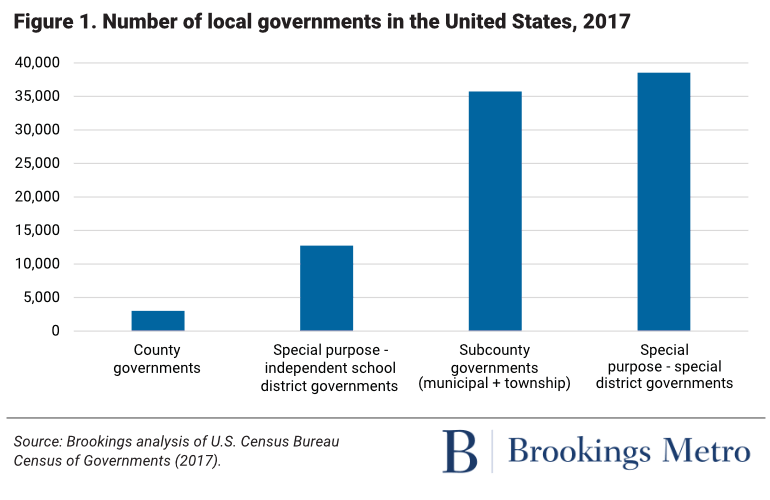

There has clearly been significant demand for expanding this sort of hyperlocal governance capacity. In addition to the massive proliferation of homeowners associations, special districts like BIDs have rapidly expanded to the point where they are now almost as common as general purpose local governments (Figure 1). While these organizations typically engage in important community functions the public sector won’t or can’t take on—from maintaining and programming public spaces to small business assistance and beyond—many have also faced widespread challenges to their legitimacy, transparency, accountability, fairness, and capacity, particularly when it comes to the homeless or other marginalized populations. For example, some BIDs have been criticized for displacing people experiencing homelessness under the guise of claiming to help. Others have been criticized for not intervening enough. In the name of defending public space for shared use by all rather than occupancy by a few, place governance organizations have often failed to strike a balance that allows public spaces to work for everyone.

While sometimes framed as incompetence or even malice, the fact is that there is a wide gap between the outsized responsibility many of these organizations bear to address homelessness (given the hyper-segregation of those experiencing it) and the capacity of these entities to do so given the scale and complexity of the challenge. Yet they are also uniquely positioned to help bridge that divide—to reach across, rather than exist within, boundaries typically erected by sector (e.g., real estate or service provision) and geography (e.g., neighborhood, tax district) to create a more integrated and inclusive service system that meets individuals who are unsheltered where they are. Some organizations are already taking this approach. For example, in 2018, Central Atlanta Progress and the Atlanta Downtown Improvement District hired a dedicated case manager focused on addressing the holistic needs of the unsheltered in and around Woodruff Park, building on other efforts to address homelessness in the area. And in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Urban Alchemy employs people with their own lived experience related to homelessness to engage and assist the unsheltered to improve safety and maintenance of public spaces for them and for other users. Still, most regions lack a comprehensive strategy to address homelessness that coordinates social service providers, housing agencies, healthcare and other city agencies with place-based organizations and public space managers—strategies that could help facilitate the transition of unsheltered individuals in public spaces into an appropriate Continuum of Care, and ultimately, into stable housing. Big metropolitan areas can contain a dozen or more Continuums of Care, and most do not include public space managers.

Elena Madison (Project for Public Spaces) and Joy Moses (National Alliance to End Homelessness) will discuss these issues in depth in their forthcoming chapter of “Hyperlocal: Place Governance in a Fragmented World,” to published by Brookings Press this spring. Through seven additional chapters written by authors from around the country, the book examines both the tensions and benefits associated with governing places in an increasingly fragmented—and inequitable—economic landscape. It provides nuanced insight into the role place governance plays in both contributing to and combating place-based socioeconomic inequities. Finally, it highlights how we can create and sustain more effective and inclusive place governance structures that support all members of a community—to not simply survive, but to thrive.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

To address homelessness, place governance must evolve

December 1, 2021