Ever since the 2018 election, the storyline around the Democratic Party has been at odds with the facts. The Democratic Party is, as it has been for many decades now, a center-left party and not a left-wing party in the style of European political parties. In the first Democratic debates in June, many of the candidates fell blindly into far-left ideological traps, causing panic among Democrats concerned about beating Trump.

But by round two of the Democratic debates, it was clear that some of the candidates had done a little homework and learned a little history.

With some exceptions, the American electorate changes slowly. For nearly four decades, the ideological composition of the electorate in presidential elections has remained more or less the same. As the following table (updated from a paper I published with my colleague William A. Galston in 2011) shows, there is no possibility of a purely liberal or purely conservative governing coalition: “To win, each party needs to form a coalition with moderate voters. But the structure of those coalitions is very different.”

Although the number of self-identified liberals has increased in recent presidential elections, they are still out-numbered by self-identified conservatives.

Table 1: The composition of the electorate in presidential election years

| 1980 | 1984 | 1988 | 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | |

| Liberal | 18 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 22 | 21 | 22 | 25 | 26 |

| Moderate | 51 | 44 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 49 | 45 | 44 | 41 | 39 |

| Conservative | 31 | 35 | 33 | 31 | 34 | 30 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 35 |

Source: CNN National Exit Poll

Playing only base politics is a dangerous game. For instance, President Trump may be making a big political mistake in spending so much attention on fueling his racist, immigrant-hating, xenophobic base. It cost him the votes of moderate suburban women (and other groups) in 2018, and Democrats and some Republicans think it will cost him in 2020. But if base politics is bad for Republicans, playing only to your base is even more dangerous for Democrats because of the simple fact that the Democratic base is smaller. While neither party can write off moderate voters, Democrats need them more than Republicans do. Table 2 shows that in the years when Democrats have won the presidency, they’ve done so by winning more than 55% of the moderate vote.

Table 2: Democratic share of the major party moderate vote

| 1980 | 1984 | 1988 | 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2012 | 2016 |

| 46 | 47 | 51 | 61 | 62 | 53 | 54 | 60 | 56 | 52 |

Source: Author’s calculation based on CNN National Exit Poll. In the bolded years, Democrats won the presidency.

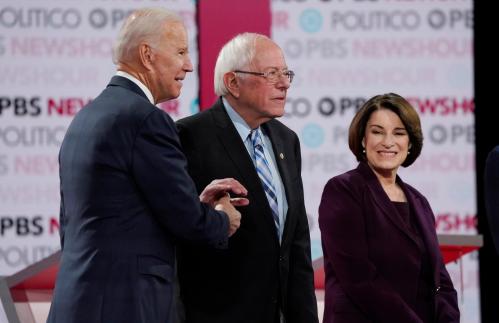

This week, the Democratic race moved into a new and more realistic phase. Clearly some of the contenders got the message about the dangers of moving too far left. Early on in the first night’s debate, former Congressman John Delaney (Md.) called for “real solutions, not impossible promises.” Sen. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) said her bold ideas were “grounded in reality.” For 45 minutes, they attacked Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) on Medicare-for-All—especially the provision that would take away private insurance. Congressman Tim Ryan (Ohio) contended that union members who have fought so hard for good health care coverage would be unhappy to learn that Sanders’ plan would take it away from them. He also pointed out that the problem with giving illegal immigrants free health insurance is that “everyone else in America is paying for health insurance.” Warren held her ground as did Sanders, but the attack of the centrists never let up.

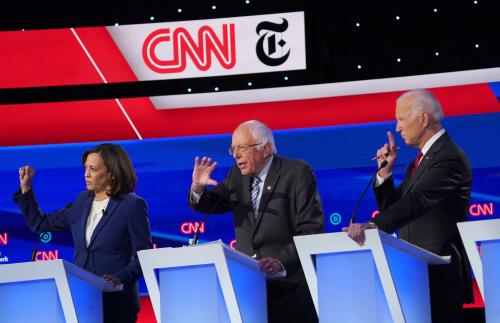

Night two of the Democratic debate was not very different, but this time former Vice President Joe Biden, the leading centrist, was the punching bag. Nonetheless, the fault lines were similar. The fight over Medicare-for-All centered, once again, on whether Americans would be allowed to keep private insurance. Biden defended the centrist option—Obamacare plus a public option—and contrasted with another dimension: the $32 trillion in taxes he said Sanders’ bill would cost. The debate moved on to immigration, where several candidates attacked Biden and Obama for the deportations that happened in the Obama administration. They also attacked Biden on crime, but Booker, Harris, and de Blasio turned out to have clay feet on that issue, since each one of them had been in positions where their pursuit of justice was less than perfect and open to criticism.

Unlike the first debate, Biden was more energetic and ready for the attacks against him. He reminded everyone of his work with President Obama, something that will probably help him hold onto his support among African Americans and other mainstream liberals who happily voted for the 44th president. Biden’s performance was just good enough to stop the bleeding, and he probably disappointed the other centrists hoping to step into that lane. But in contrast to the first debate, it is now clear that at least there is a centrist lane in the Democratic primary which, as history tells us, is not a bad place to be. It may well be the path to the nomination.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The second Democratic debate: Opening up the centrist lane

August 1, 2019