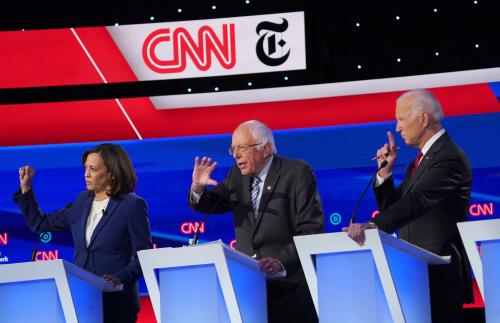

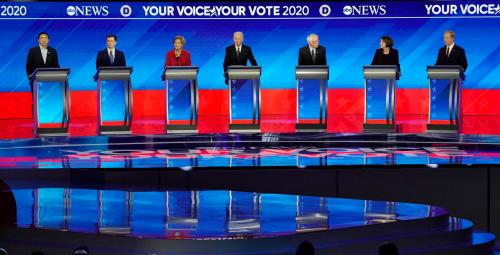

Seven Democratic candidates convened in California tonight for the latest Democratic presidential debate. With the Iowa caucuses looming in just 46 days, each faced a different strategic task. As the debate proceeded, how well did they measure up to their challenges?

For the two frontrunners, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, not much has changed during the past 12 months. One year ago, Biden was at 29 percent and Sanders at 17.7 percent in the Realclearpolitics average of polls. This December, Biden is at 27.8 percent and Sanders is at 19 percent. Because of this remarkable stability, they had the easiest job. Each is well known, with a clear political identity, and each has much-discussed flaws. Sanders strikes some observers as humorless, repetitive, and too far to the left. While his call for political revolution excites some voters, it scares others. During the debate he refrained from calling for a revolution or even saying the word until his closing statement. But other than that, he was the candidate he has been since 2016.

Joe Biden is well liked, but his campaign has been devoid of vision and energy, giving rise to fears that he no longer has what it will take to run an effective campaign against President Trump. But the debate illustrated why he remains in the front of the pack. There is an old-fashioned common sense about Biden. For instance, one of the questioners expressed skepticism that America after Trump could return to normal and Biden said, “I refuse to accept the notion that we can never get cooperation again. If that’s the case we’re dead as a country.” The two frontrunners went at it about Medicare for All—the most regularly debated issue in all these debates. And then Senator Amy Klobuchar stepped in with another bit of solid common sense “I think you can be progressive and practical at the same time.”

Biden’s closing statement was especially powerful in light of his heated argument with Sanders over Medicare for All. “Level with the American people,” said Biden. “Don’t’ play games.”

After Biden and Sanders we saw a three way scramble between Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, and Pete Buttigieg. After a meteoric rise through the summer and early fall, Warren’s campaign stumbled on the issue of Medicare for All. By releasing a detailed funding plan, she publicly embraced a level of new taxation that gave many of her supporters pause. When she modified her plan to allow for a phase-in period through the public option, she raised doubts about the level of her commitment to what began as Senator Sanders’ proposal. These shifts appear to have fueled concerns about her electability that have increased markedly since September.

When Warren’s campaign was surging, she was gaining support from both left-leaning voters who identified Sanders as their second choice and from upscale professionals who put Pete Buttigieg second. As Warren’s campaign has lost altitude, she has bled support to both Sanders and Buttigieg. Her challenge in the debate was to wage a two-front war to regain lost territory. This explains why she went after Mayor Pete for holding a fundraiser in a rich man’s wine cellar and drinking $900 bottles of wine. Mayor Pete was obviously ready for the attack. He could lay claim to being the only candidate on the stage who was not a millionaire or billionaire. “This is the problem,” he said to Warren, “with issuing a purity test you can’t pass.”

Pete Buttigieg has been the surprise of the campaign. Beginning as a little-known mayor of a mid-size city in Indiana, he has impressed Democrats with his intelligence, eloquence, and sure-footedness. In polls taken during the past month, he has led the field in Iowa. But doubts remain. Can Buttigieg broaden his appeal beyond his core supporters—educated, upscale voters—to include African Americans, with whom he has had a rocky relationship at home and across the nation? Can a 37-year-old never elected to statewide, let alone national office attain the stature needed to be an effective presidential candidate? Right after Senator Warren hit him (figuratively) with the $900 bottle of wine, the other woman on the stage, Senator Amy Klobuchar, compared his “talking points” to the extensive amount of government experience and accomplishments represented on the stage by all the other candidates (minus Andrew Yang and Tom Steyer). “We should have someone heading up this ticket who can actually win,” she said, referring to the fact that Buttigieg had lost a statewide election. “I think winning matters, I think a track record of getting things done matters.”

Amy Klobuchar is the new wild card in the race. For months she patiently presented herself, without much success, as an experienced moderate candidate with broad-based support at home and solid roots in the Midwest—the kind of candidate who could deliver those crucial midwestern states that Hillary Clinton lost so narrowly. It was only in the October and November debates that she began to break through with performances that melded humor and firmness. A recent survey showed her breaking into double digits in Iowa, just two points behind Warren. Klobuchar’s task in the debate was to build on the momentum of her previous debates and underscore her credentials as a practical reformer who can compete more effectively for rural and small-town votes than can anyone else in the field. On that point, tonight was perhaps her best performance of the election cycle. She was forceful, pragmatic, and was the only other candidate on the stage besides Biden who made a compelling case for her electability.

At the other end of the political continuum, Andrew Yang and Tom Steyer faced the same challenge going into the night that they have faced in previous campaigns: persuading voters that they were more than niche candidates and had plausible paths to the nomination. There was a lot of discussion about billionaires—after which Steyer came into the conversation and changed the topic to Trump and the economy. The billionaire bashing doesn’t bode well for Steyer and yet no one attacked him directly—for good reason. Anyone who wins the nomination hopes that Steyer will open up his checkbook for the November election.

Of course, there are Democratic candidates out there still campaigning and it is possible, but not likely, that one of them can break through. The most intriguing is former New York City Mayor and billionaire Mike Bloomberg, who will test the proposition (based on considerable evidence) that skipping the early contests is a ticket to nowhere. Bloomberg’s narrow path rests on the hope that three or even four candidates could each win one of the contests in February, leaving the party without a clear front-runner and heightening the importance of Super Tuesday, when Bloomberg will be on the ballot for the first time.

The final Democratic debate of the year ended with the race pretty much where it began—two white men in their late 70s and a group of younger, more diverse candidates seeking to break through. It’s not clear that Warren reversed her slide, nor is it clear that Buttigieg helped himself. However, the star of the night would appear to be Amy Klobuchar.

The next debate, however, will be in Iowa, only a few weeks before the Iowa caucus when we will see who has connected with real voters and who has not.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Democratic Debate: Sens. Klobuchar, Warren take on Mayor Pete

December 20, 2019