Higher rates of COVID-19 infection among essential and frontline workers put a spotlight on underinsured laborers. Essential workers—those who perform a range of jobs and services that are necessary for society to function well, including but not limited to occupations in health care, food service, and public transportation—are less likely to have insurance and are more likely to be underinsured than non-essential workers. However, a 2020 Brookings report found that Black essential workers are more likely to be uninsured than white essential workers. Similarly, an Urban Institute analysis found that Black workers are more likely to be essential and frontline workers (a sub-category of essential workers comprised of people who cannot work from home), and they are more likely to be underinsured. The Urban Institute study adds that the problem of not having adequate insurance is even more acute for American Indian or Alaska Native and Latino or Hispanic workers. In order to achieve equity for the lowest paid and most essential frontline workers of color, the American health insurance and health care systems need a radical restructuring.

The concentration of Black people in essential jobs did not develop through happenstance. Racism in labor markets is revealed in racial disparities in occupational concentration, employment rates, and pay. For instance, Black people in Minneapolis, as in much of the nation, are more likely to work in jobs considered essential—transit, factories, retail, health care facilities, and childcare—which increases their exposure to COVID-19. In the state of Minnesota, Black people make up 7% of the total population, and account for approximately 25% of all COVID-19 infections as of the summer of 2020, according to a University of Minneapolis study. There is a causal relationship between wealth and quality of life outcomes, including health. Wealth is the sum of all assets owned minus debt held—a person’s net worth. Occupational discrimination factors into how much wealth a family has and the resultant degree of protection a family has to withstand inevitable economic shocks.

Medical debt among Black workers adds insult to injury. An examination of debt as a function of wealth provides insights into structural racism—the policies and practices that produce racial disparities. Therefore, we introduce evidence that by reducing the amount of medical debt held by all households, we are disproportionately helping Black people. This will signal that we are mitigating structural racism and improving conditions so that Black workers and their families can thrive. This report examines medical debt and its racial distribution with a focus on how it’s accrued, including failures in the insurance market and malign medical billing practices. Following that discussion, we review a number of policy reforms to reduce health care cost sharing that broadly would move the nation further toward universal health care.

Ways that people accrue medical debt

According to a study from the Journal of General Internal Medicine, 137 million adults experienced difficulty paying medical bills in 2017, and young uninsured adults were about twice as likely to face hardship paying for health care compared to those with some public or private insurance. Kaiser Family Foundation found that about one in four adults aged 18-64 had trouble paying a medical bill over the last 12 months.

Many workers would not stay in riskier, low wage jobs if they had better health insurance options. Workers, essential and otherwise, stay in suboptimal employment because their employment is tied to their health insurance. “Job lock” is a phrase used to describe how workers feel tied to imperfect employment. According to Gallup, one in six workers experience job lock due to their health insurance coverage. Decoupling employment and health insurance could reduce job lock, which would free up people to start businesses and would increase wages because employers could reallocate insurance costs toward employee pay.

But not all workers receive health insurance from their job to even experience job lock, especially low wage essential and frontline workers. In fact, even after the Affordable Care Act, in the first half of 2020, 30 million Americans were without health insurance entirely, and Black, Latino or Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native people are more likely to be uninsured. Living without health insurance was a cause of a great deal of stress for many Americans even before the pandemic. During the pandemic, states with higher rates of uninsured populations saw worse outcomes and uninsured Americans are half as likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine even though it’s free.

Uninsured Americans may be right in being distrustful of so-called “free” healthcare. Private nonprofit hospitals often do not treat people who are unable to pay as charitably as policymakers may hope. Studies by National Nurses United found that Johns Hopkins Hospital, a private nonprofit hospital, received over $164 million in tax exemptions in 2017. The tax exemptions were created to remove the profit motive of medical care and instead instill a motive of community and individual care. Instead, Johns Hopkins Hospital sued patients resulting in wage and property garnishments to collect a median medical debt of $1,089.

Health debt is associated with decreased use of medical services. According to NORC at the University of Chicago, Americans are more afraid of the cost of the medical coverage than the underlying illness. Due to cost sharing, low-income individuals are particularly averse to using health services, and, if and when they do, their symptoms and diagnoses have worsened, increasing health expenditures. According to our analysis, 4.4% of all households and 6.2% of Black households have high medical debt (defined as medical debt of over 20% of yearly household income). These households with high medical debt are at acute risk of decreased medical usage. Seniors, and particularly low-income seniors with chronic diseases, are more likely to become nonadherent to medical and medication prescriptions due to costs.

For those who are insured, medical bills, particularly through surprise billing, may also keep many from getting the care they need, including getting vaccinated. Surprise billing—when insured people unknowingly get care (and bills) from providers that are outside of their health plan’s network for emergency care—was common until the passage of the No Surprises Act at the end of 2020. A study from Health Affairs found that, while insurance companies will pay for larger medical expenditures, “the more modest amounts—for which patients are responsible, under common forms of coinsurance—may still be unaffordable to many people.” According to our analysis, 17.4% of households with insurance have medical debt compared to 27.9% of households without insurance. Conditional on having medical debt, households with health insurance have an average of $18,827.25, while households without health insurance have an average of $31,947.87. Clearly, having health insurance lowers the likelihood of medical debt and lowers the amount owed, but even households with health insurance are at risk of becoming indebted due to an illness or injury.

The extent of the medical debt problem is not well known nationally because there is not a centralized location where medical debt is held. The easiest place to look is collection tradelines—when hospitals and other medical providers send unpaid bills to debt collectors. According to the CFPB, roughly half of all collections tradelines are due to medical bills, affecting nearly one in five consumers in the credit reporting system. Medical debt is a leading cause of consumer bankruptcy. In 2007, at least 62% of bankruptcies were, at least partially, attributable to medical debt. Even after the advent of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, that number has not decreased significantly.

An article published in JAMA, looking only at these collections tradelines, found that in 2020 the average medical debt in collections was only $429. Not included in researchers’ calculations are medical bills that patients owe directly to providers, long-term payment plans, debts paid with credit cards, and arrears in litigation. In general, healthcare services researchers rely heavily on these collections claims data, which as stated earlier, offer an incomplete picture of the total medical debt held by households. So, the extent of the problem is significantly underestimated in the JAMA study as well as in most studies using collections tradelines. Therefore, more robust data collection methods for patient billing, expenditures, and payments are critical to understanding the barriers to achieving quality public health.

For this analysis, we use survey data to estimate the amount of medical debt held by American households. Summary statistics from the Census Bureau, whose data we use in our analysis, show that nearly one in five households have medical debt. And most estimates put the number between $81 and $140 billion, although some put it as high as $1 trillion. According to our analysis, 18.5% of households have medical debt. Conditional on having medical debt, the average amount of medical debt is approximately $20,500 and the median amount of medical debt is about $2,000. This suggests that while most households with medical debt have a relatively small amounts of medical debt, some households carry significantly higher liabilities. The consequences often lead to seeking less medical attention in the future. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals not getting the care they need can have societal implications. The extent of the problem may not be fully understood, but the consequences can be devasting to individuals and society.

Findings

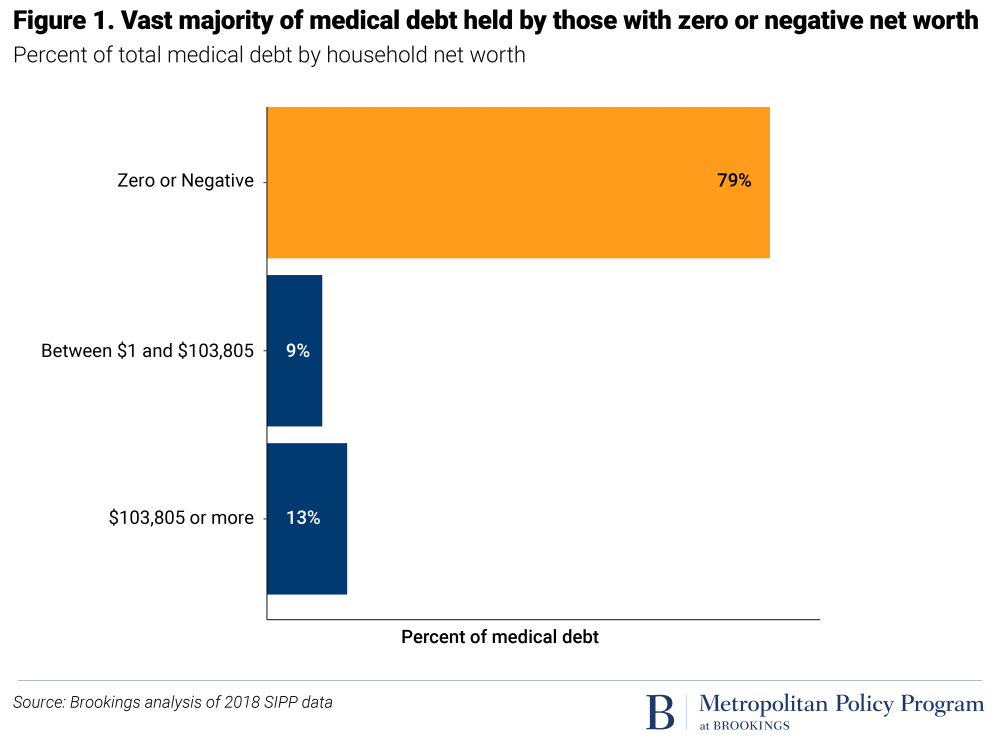

Nearly 80% of medical debt is held by households with zero or negative net worth. The blame for a lack of health care coverage should not be rigidly characterized as a class issue. Black households are more likely to hold medical debt. Twenty-seven percent of Black households hold medical debt compared to 16.8% of non-Black households. These findings corroborate a 2020 Urban Institute report that found medical debt was also higher and more concentrated in communities of color than in white communities.

As we have said, having health insurance does not mean that households are able to pay their medical bills. Non-Black households without health insurance are only slightly more likely to have medical debt than Black households with health insurance.

Black households are much less likely to have private health insurance. Conditional on having private health insurance, Black households are about as likely as non-Black households to receive their insurance through work. On average, employers pay 82% of workers’ health insurance premiums and 70% of workers’ families’ health insurance premiums. But Black employees are more than 70% more likely (11.5% vs. 6.7%) to work for employers that do not contribute to their insurance premiums.

Households with medical debt are significantly less wealthy than households without medical debt. Non-Black households with a positive net worth, regardless of medical debt status, have a higher net worth than Black households. This disparity reflects how the vast majority of medical debt is held by households with negative net worth.

Black households are more likely to have medical debt at every age, but this debt disparity is particularly acute for Black households past retirement age, when households have access to Medicare. Black households past retirement age still holding medical debt reflects how Black seniors have been denied the ability to build wealth.

Eliminating medical debt has a small ameliorating effect on the racial wealth gap, benefiting Black people the most. Here, we repeat the methodology from our analysis of student debt. Cancelling medical debt shifts wealth up more for Black households than non-Black households, possibly revealing the impact of anti-Black racism on health outcomes, but certainly revealing the impact of anti-Black racism on access and coverage.

Eliminating medical debt decreases the numerical racial wealth gap most for low and negative wealth households. There is little difference for households above the 25th percentile.

To really understand the racial wealth gap, the relevant metric is the wealth ratio—for example, when our colleagues wrote that “the median white household has a net worth 10 times that of the median Black household.” We plotted the ratio of the racial wealth gap at every wealth percentile to examine the relative effects of eliminating medical debt and find that the elimination of medical debt does decrease the racial wealth gap, albeit much less than the elimination of student loans. Again, this relative reduction in the racial wealth gap was most pronounced for low-wealth households.

Policy recommendation

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Sen. Bernie Sanders proposed eliminating medical debt. While congressional action to eliminate medical debt would be welcome, and the authors would support such action, unlike student debt, which is held mainly by the federal government, it is much more difficult to assess the size of the medical debt problem, where such debt is held, and how cancelling medical debt would work in practice. We argued for student debt cancellation because the vast majority of student debt is held by the federal government, and Congress has already given the Secretary of the Department of Education the authority to cancel student debt unilaterally. Similar action for medical debt would require that the government purchase medical debt held by hospitals, colleciton agencies, credit card companies, and banks. Nevertheless, there are more realistic and achievable policy solutions that prevent families from acquiring the medical debt that has such deleterious affects on their health and lives. We’ve been thankful for essential workers for the last 18 months, but we have not demonstrated our appreciation to them. Providing universal health care that does not require significant cost-sharing, as we will outline, will be a first step in thanking these workers.

Separate health insurance from employment

Employer-sponsored health insurance ties health to labor, reinforcing the centrality of profit over well-being. Incentivizing employers to sponsor health insurance has only served to widen racial, ethnic, and income inequities in access to health care—a direct result of systemic racism. Low-wage essential and frontline workers are chronically underinsured, often because they work in low-wage jobs that do not provide fringe benefits such as health insurance or paid sick leave. As a result, high out-of-pocket medical costs such as co-payments, insurance premiums, and deductibles disproportionately affect these communities. Additionally, the drawbacks of employer-sponsored health plans often supersede their advantages—disadvantaging not only employees but also employers. In particular, employer-sponsored plans tend to be buried in bureaucracy and red tape, given that they are often complex and require administrators to oversee and define employees’ coverage.

The current system of employer provided health insurance shields households from paying taxes on their earned health insurance benefit. Employer provided premiums are shielded from income taxes, reducing workers taxable income. According to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, “The ESI exclusion will cost the federal government an estimated $273 billion in income and payroll taxes in 2019, making it the single largest tax expenditure.” This tax deduction is worth significantly more to workers in higher-income [and thus higher tax] brackets than workers in lower-income [and correspondingly lower tax] brackets. Further, according to a study in the National Tax Journal, “five-sixths of the benefits [flow] to the top half of the income distribution.”

In order to separate health insurance from employment, Congress should continue to improve the online health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act, empowering consumers—rather than employers—to choose their health care coverage. By design, online health insurance marketplaces are able to provide the same benefits to all who need coverage, which can substantially reduce inequities in access to care and job lock. Improvements in health insurance marketplaces can make them an even more viable option for coverage, rather than a last resort. Making health insurance marketplaces more viable, providing a subsidized public option, and expanding existing health insurance subsidies will both protect and empower consumers as they seek health care.

Other OECD countries have helpful models of universal health care coverage. Germany’s Bismarck health coverage model of insurance nonprofits has similarities to the United States’ system, yet it places less financial burden on consumers. The Bismarck model is a multi-payer system in which employers and employees finance health insurance. However, the government controls much of the cost-sharing. Further, the Bismarck model must cover everyone, and does not make a profit on offering coverage. In turn, the Bismarck model takes steps toward providing universal health care without financially burdening the consumer.

The United Kingdom’s National Health System (NHS) has publicly run hospitals that function essentially as a Veterans Administration (VA) for all. Right now public hospitals exist only as safety net providers such as community clinics and health centers that meet critical gaps in health care coverage for uninsured and underinsured people, even if they are not able to pay for the service. Yet these safety net providers tend to have fewer resources and capacity to serve people. If we were to transition to a public hospital system like the NHS, Congress must ensure that these public institutions have enough resources and capacity to ensure access to quality health care for uninsured and underinsured people.

In a single-payer system, one public or semi-public entity would finance health care for all. For instance, Canada’s federal government and the country’s 13 provinces and territories co-fund the country’s health system, known as Canadian Medicare. Each government in Canada’s 13 provinces and territories is responsible for administering insurance plans, health services and supervising health care providers in their respective areas. Under the Canada Health Act, each province and territories’ health insurance plans must be “publicly administered, comprehensive in coverage conditions, universal, portable across provinces, and accessible.” These regulations ensure that there is equity among local insurance plans. Further, there is no cost-sharing in the Canadian Medicare system, as physicians cannot charge patients above the government’s negotiated fee schedule. Despite its largely universal coverage, Canadian Medicare coverage excludes oral and vision care, prescription medication, and rehabilitation services. Employer-based insurance, which about two-thirds of Canadians hold, helps supplement these services. Nonetheless, all Canadian citizens and permanent residents have free access to medically necessary health care services upon the time of use.

Public hospitals, universal single-payer health insurance, or a German-style Bismarck system of insurance nonprofits are all feasible options that take first steps toward universal low-cost health care in the United States. We call on Congress to empower and protect consumers seeking health care coverage by continuing to work toward universal health care regardless of the model.

As we have shown, having health insurance does not guarantee access to quality health care if it goes unused due to fear of costs. Correspondingly, health insurance, private or public, does not insulate households from medical debt. The American health system has made two choices that ought to be rethought.

First, American health care system uses a fee for service model. Writing for Brookings, scholars at Duke University and the World Economic Forum said that “variation in quality and access across systems shows that paying providers for traditional service delivery is not sufficient for meeting [universal health care] goals.” Our former Brookings colleagues suggested several models for rethinking payment schemes. Whatever choice that policymakers make has consequences and trade offs, but it is vital to understand that retaining the status quo is a choice with trade offs as well.

Second, American health care shares costs. Cost sharing impacts equitable access to care. Different health systems have different methodologies for cost sharing, but one thing in common amongst most other OECD countries is that the cost at point of service is either free, very low, or a percentage of household income. Financial incentives for health services are not standardized among health care providers, and providers tend to use expensive services or items when they are not medically necessary. As a result, patients may receive care that they do not need or want. Cost sharing hurts patients, again centering profit over well-being.

As we contemplate universal health care, which President Joe Biden has said is a basic right, we should also consider how our cost sharing methods push low-wealth households further into debt and bankruptcy. Within this new system, consumers could have less financial burden as they access health care.

Hold nonprofit hospitals accountable for providing community benefit services

Congress should ensure that there is greater federal oversight around community benefit services, which are intended to offer funding to nonprofit hospitals that provide free or reduced cost health services to low-income and medically indigent people. Congress should work toward establishing measures that increase hospital transparency around using community benefits. Congress should also require that providers discuss hospital financial assistance options as well as billing and collection policies with patients receiving care under community benefits. Federal policymakers should also ensure that nonprofit hospitals are using precise accounting standards for community benefit services and have a minimum threshold for community benefit spending. Further, nonprofit hospitals should be required to spend community benefit dollars on identified community needs and provide detailed explanations of the types of activities that qualify for community benefit spending. These measures can ensure that nonprofit hospitals are held accountable for providing care to the communities that will not be able to access it elsewhere.

Further, we recommend that states offer a similar level of oversight to the federal government in nonprofit hospitals. For instance, states can enact audits to determine how community benefit spending has impacted communities, require hospitals to contribute to community service efforts, require transparent reporting on community benefit uses, and count community investments in housing, economic development, child care, and mentoring as community benefits. States can include community benefit requirements in their hospital licensing programs and consider requiring minimum community spending thresholds for hospitals. These strategies, along with clear reporting requirements, can encourage hospitals to truly invest in the communities they serve.

In addition, the Affordable Care Act requires nonprofit hospitals to conduct community health needs assessments, which allows hospitals to identify organizations to which they can provide community benefit funding. We recommend that hospitals with community benefits provide unrestricted funding to community-based organizations led by people of color, as they tend to be more established in the community and offer a variety of health, social, and behavioral health services to community members. Such an approach allows for hospitals to collaborate with the communities they serve and engage in trust-based giving. Finally, there should be oversight at the state and federal level to ensure that there is adequate funding for safety net providers, such as community health workers and Federally Qualified Health Centers. Further, policymakers should put measures in place to ensure that safety net providers are not able to sue underserved or low-income patients for not being able to pay their medical bills.

Remedies for surprise billing

Congress should ensure that health care providers and insurers prioritize patient health and well-being over individual profit. Prioritizing individual profit over health and well-being has resulted in the consumer bearing the burden of health care costs—rather than addressing the ways that insurance companies, provider billing policies, and the federal government have impacted access to affordable care.

Congress has made strides toward centering patient well-being by enacting policy to protect patients from unanticipated medical costs. The No Surprises Act, which became law as a part of last year’s omnibus spending bill, includes critical protections to protect consumers from unexpected out-of-network health care bills. Effective January 2022, health plans will be required to cover surprise bills using in-network, rather than out-of-network, rates. Further, out-of-network providers for emergency services will not be allowed to balance bill, which refers to billing patients the difference between the provider’s charge and the allowable service fee, beyond the applicable in-network cost sharing amount for surprise bills. Among other provisions, providers who are out-of-network will not be able to send patient bills for extra charges. Further, out-of-network providers cannot send patients bills for excess charges.

Policymakers should continue to ensure that there are measures in place to maintain oversight on consumer protections. Such measures should include ensuring that hospitals are transparent in their reporting, requiring hospital audits, and carefully reviewing any complaints of health care providers or issuers violating surprise billing protections.

Build more robust data collection systems

As noted earlier, it is challenging to uncover the extent of the nation’s medical debt problem, because, unlike student debt, there is no centralized system or database where debt is held. Health care data are similarly decentralized. Typically, research on access to health care services uses administrative claims data, which is notoriously complex, incomplete, and unstandardized. Further, health data exists in many different formats, including images, videos, text, and scans, again making centralizing information challenging. In order to better understand the nation’s medical debt, stronger, more transparent, and centralized data collection methods are critical to protecting patients’ health.

We call on Congress to take steps toward standardizing assessment and quality improvement measures, requiring data collection and disaggregation by race and ethnicity, and increasing surveillance and research on health outcomes. Policymakers should ensure that hospital providers collect patient data by directly asking patients, rather than only gathering information through observation alone. Further, steps should be taken to standardize billing codes across health providers and health insurers—which can prevent creative coding, a method of medical billing which often results in health providers receiving increased or exaggerated profits rather than a fair rate for their service.

Finally, policymakers should support efforts toward establishing a centralized, streamlined data-sharing system that houses hospital and health care plan data within an entity such as the National Institutes of Health. Such a system would allow for analysts and policymakers to better uncover the extent of medical debt in the nation along with gaps in health care coverage. The National Institutes of Health launched the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) during the pandemic to help advance research on the virus. Members of the N3C collaborative are currently building a data enclave that will allow for rapid data collection from hospitals and health care plans. N3C illustrates that centralizing health care data sharing is possible. Congress should work toward expanding funding to support such efforts, not only for research on COVID-19, but also for all health outcomes data.

Conclusion

President Joe Biden has stated, “Health care is a right … not a privilege”—a theme that was repeated on the campaign trail and during his presidency. However, maintaining a health care system that ensures that many take on debt while others don’t ensures that it will be a privilege. Employer-based health care facilitates unequal treatment. As with many issues, the pandemic simply exacerbated existing inequalities. Essential and frontline workers, mothers and others knew too well, long before the pandemic, that their work is significantly underappreciated. Providing universal health care that does not require significant cost-sharing would be a first step in thanking these workers as well as others who deserve more than our applause.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).