Payment reform in health care is confusing, but the goal is simple: How can health care providers change their economic incentives to encourage value over volume? If you’ve wondered about how these new payment models work, we’re here to help. And if you want to see Dr. Patrick Conway, the head of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, talk about it more in depth at our most recent MEDTalk event about oncology care reform, click here.

Where are we now?

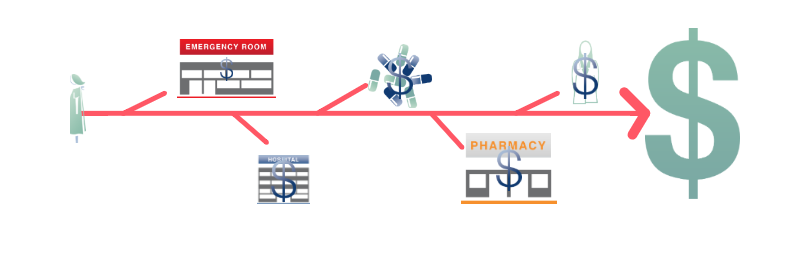

Fee-for-Service. Traditionally, health care providers are paid in a “Fee-for-Service” (FFS) model. This is exactly what it sounds like: every time you have a blood test, a doctor’s visit, a CT scan, or any other service, you (and your insurance company) pay separately for what you have received. Over the course of a long treatment or a chronic condition, that can add up to a huge expense.

The Fee-For-Service System

It is well known that FFS is draining the entire health care system. When paying for volume, a sick patient is worth more than a healthy patient , and this status quo results in uncoordinated care, duplication of services, and fragmentation. After all, the more doctors and providers do, the more they get paid.

Reformers hope to replace the traditional FFS model with something better, and they’ve come up with many different models of payment that could allow this to happen. (Note to reader: these are simplified explanations; policy enthusiasts can learn much more about them through the Engelberg Center’s Merkin Initiative).

Here are four widely proposed and increasingly popular alternative payment models:

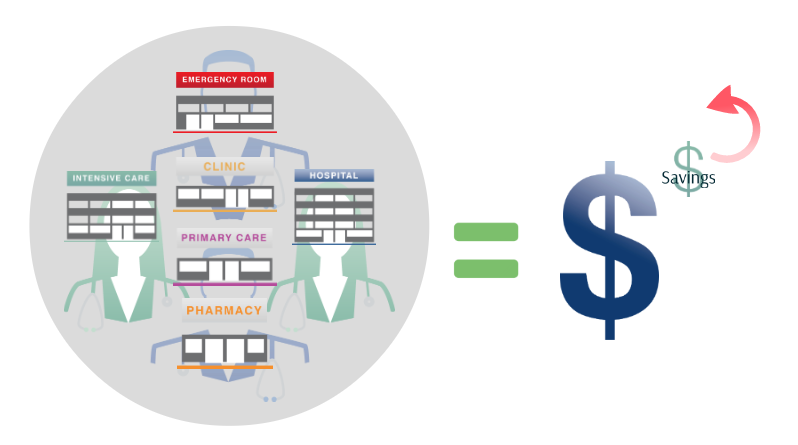

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are groups of providers across different settings– primary care, specialty physicians, hospitals, clinics, and others – who chose to come together to jointly share responsibility for overall quality, cost, and care for a large patient population. These providers recognize that poorly coordinated care from these entities can lead to increased costs from things like redundant tests and overlapping care.

Accountable Care Organization Model

Here’s how it works in basic terms: the ACO physicians bill the way they always do, but the total costs get compared to an overall target. Plus, they have to measure some of their patient outcomes, to prove that they hit certain quality benchmarks. If costs are higher than the target, the ACO may get penalized. In the end, if they are under the cost target and satisfy their quality measures, they get a share of the savings.

By bringing all of these providers under the umbrella of an ACO, caregivers can all be on the same page, and the patients ideally receive coordinated care with a focus on prevention – since providers are encouraged to keep their patients healthy and not just earn more by doing more tests and procedures.

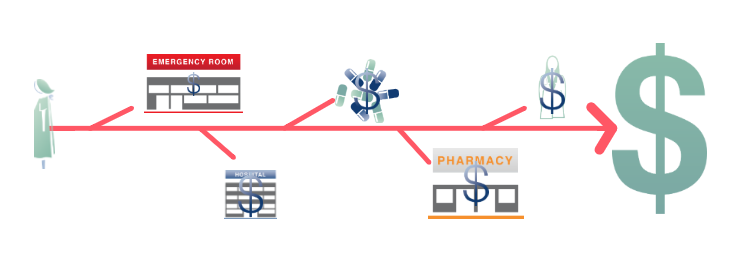

Bundles: A health care bundle estimates the total cost of all of the services a patient would receive per episode over a set time period for a certain problem, like a knee replacement or heart surgery. For example, a payer such as Medicare or an insurance company could calculate that a hypothetical 30-day bundle for a knee replacement surgery costs $10,000.

Without Bundled Payment…

The payer reduces the total cost of the episode by 2-3%, and hands the bundle over to the provider – in the knee surgery example, that becomes $10,000 minus 2%, so $9,800. The provider is then responsible for all costs of treatment – whether or not it exceeds the amount of money they were originally given. This encourages the provider (collaborating with the entire care team) to help the patient avoid preventable complications like a hospital readmission by better managing a patient’s care.

With a Bundled Payment…

If the provider keeps costs low, they can keep the margin on the bundle, while the insurance company already saved by reducing the cost of the episode by a small percentage when they created the bundle. So, in our example, if the provider was able to meet quality benchmarks and the total cost of the 30-day episode was $9,000, they get to keep the extra $800.

Patient-Centered Medical Homes set themselves apart by providing set monthly payments on top of existing funding models, in order to fund a highly coordinated team of primary care professionals, which may include, depending on the patient’s needs, physicians, nurse practitioners, medical assistants, nutritionists, psychologists, and possibly even specialists. The team works closely to build a strong relationship with each other,with their patients and their caregivers.

Patient-Centered Medical Home Model…

This extra money can be used to hire nurses or agencies to give special care and attention (by phone or home visits, for example) to high-risk patients, with the goals of reducing emergency room visits and other preventable problems in the long run. Other enhancements might include email communication with patients, more time to call and coordinate care between primary care doctors and specialists, and so on. In the end, the savings from better coordinated care make the extra monthly payments worthwhile.

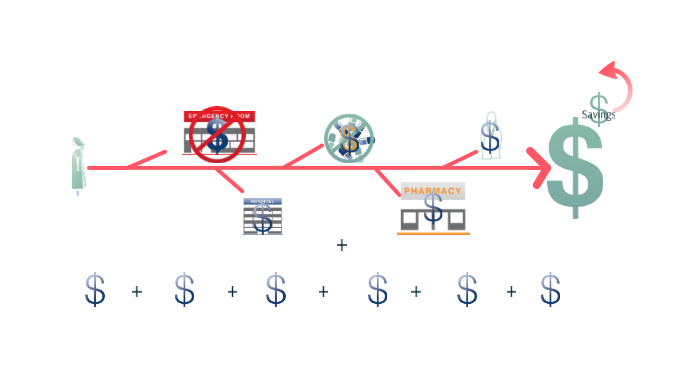

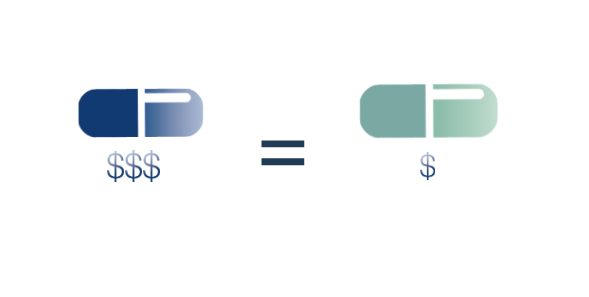

Pathways, an idea which has gained traction in oncology care, provides a system of choices and decision making tools for providers and patients in order to prescribe the most effective and least costly treatment. For example, let’s say there are two cancer drugs proven to have the same effectiveness, with no differentiation in side effects, but one of them costs less than the other.

Same Effectiveness, Different Cost…

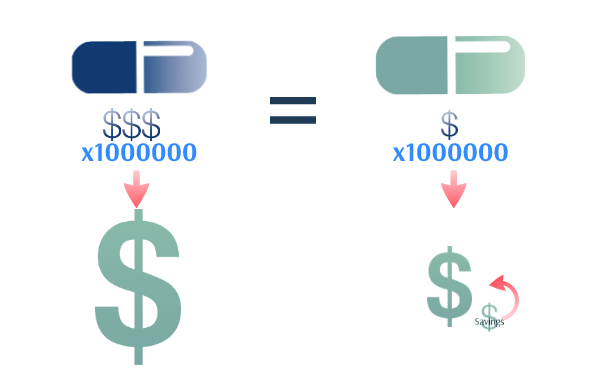

Like the medical home, the pathways model uses a “per-patient” add on fee (often much larger than for medical homes focused on primary care, since cancer patients need intensive treatment) that might encourage the provider to prescribe the less expensive of two equally effective treatments.

How Pathways Creat Savings…

When this is implemented on a broad scale, the savings could add up for payers, and defray the cost of the add-on fees.

Please feel free to use any of these images in your own work, presentations, or educational efforts, and to view and download the interactive versions here. The images should be attributed to The Merkin Initiative on Clinical Leadership and Payment Reform at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The beginner’s guide to new health care payment models

July 23, 2014