Across the African continent, the relentless spread of networks, sensors, artificial intelligence, and automation is driving a revolution to an unknown destination. Emerging technologies such as CCTV cameras with facial recognition systems, drones, robots, and “smart cities” are proliferating. Digitization is improving government revenue collection and curbing corruption. Cameras and facial recognition technologies are helping authorities respond to terrorist attacks. Drones are delivering life-saving medical supplies. Yet with each advance there is a cost. Sophisticated malware enables novel forms of criminality, surveillance technology powers new tactics of repression, drones unleash the prospect of an autonomous weapons arms race.

Emerging technology is having a powerful impact on the security and stability of African states. Yet the digital revolution’s ultimate legacy will be determined not by technology, but by how it is used. African countries that take advantage of the opportunities and limit the risks inherent in emerging technology may achieve greater peace and prosperity. Yet many countries could be left behind. As the continent recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, its leaders face a choice between harnessing emerging technology to improve government effectiveness, increase transparency and foster inclusion, or as a tool of repression, division, and conflict.

Internet penetration

The rapid spread of the internet across the African continent has been heralded as a key driver of prosperity and a sign of the continent’s technological coming of age. Today, at least a quarter of the population has internet access, a nearly fifty-fold increase in internet usage since the turn of the millennium. By 2030, the continent could achieve rough parity with the rest of the world when three quarters of Africans are projected to become internet users. The economic potential is enormous: Mobile technologies alone have already generated 1.7 million jobs and contribute $144 billion to the continent’s economy, or roughly 8.5% of GDP.

Some African countries have taken advantage of rapid increases in internet penetration to make concrete improvements in the lives of citizens. Led by the rise of platforms such as Kenya’s M-PESA, Africa has leapt ahead of other regions to become a center of mobile, peer-to-peer finance. The continent registers close to half of the world’s mobile money accounts. Sierra Leone, one of the world’s poorest countries, recently established a Directorate of Science, Innovation and Technology (DST). Its initiatives include a “national financial data architecture with embedded automated financial tools” intended to improve service delivery and reduce corruption. These are just two examples of how digitization can provide a cheap, secure source of finance to populations in need and improve government transparency in countries where official graft is a universal concern.

Nevertheless, the rapid spread of the internet across Africa has downsides. For one, without affordable internet and reliable power, broadband internet access will remain out of reach for many low-income Africans living in rural areas. The relationship between internet access and household welfare in Africa is strong: One study from Senegal associated 3G internet coverage with a 14 percent increase in consumption and a 10 percent decline in poverty. Thus, countries that do not address internet access issues risk limiting the opportunities of their citizens, exacerbating already-substantial inequality, and inflaming regional, political, and ethnic divides.

More broadly, digitization brings with it vulnerabilities that expose countries to cyber espionage, critical infrastructure sabotage, and crime. Until recently, Africa was responsible for such a negligible portion of overall internet traffic that its systems were not particularly vulnerable to sophisticated cyberattacks. That could change in the coming decade, as African states, criminal enterprises, and threat groups become increasingly prominent cyber actors. Four African states with comparatively high levels of internet penetration—Algeria, Morocco, Kenya, and Nigeria—already rank among the top ten countries by share of users attacked by mobile malware.

Technological innovation and diffusion

Just as influential as expanding internet penetration will be the development and diffusion of emerging technology. Because most African countries are low income and tend not to rank among the world’s major technological powers, it is often assumed that the terms and conditions under which African states access and use new technology is beyond their control. This has always been a questionable assumption, and it is even more questionable now, when many critical emerging technologies are cheap and widely available. Numerous African countries are already harnessing two critical emerging technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) and drones, in ways that are at once innovative and disruptive.

According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 15 African countries use AI-enabled surveillance technologies, such as algorithmic analysis and CCTV camera-assisted facial recognition to monitor and respond to crime. During a 2019 assault by the insurgent group Al-Shabaab on an upscale hotel in Nairobi, Kenya, these technologies helped authorities respond quickly and decisively. Yet surveillance technology’s overall efficacy as a crime-fighting tool is unclear. Alone, it cannot address crime’s underlying political, economic, and social causes. Reported crime in Nairobi declined between 2014 and 2015, the year after AI surveillance technology was installed, but quickly crept back up to even higher levels.

The spread of drones and other autonomous systems highlight similar opportunities and risks. In 2016, Rwanda became the world’s first country to offer commercial drone delivery, partnering with the U.S.-based Zipline to deliver life-saving medical supplies to remote rural areas. That same year, Nigeria became the first African country to publicly confirm the use of a drone in combat against a terrorist group.

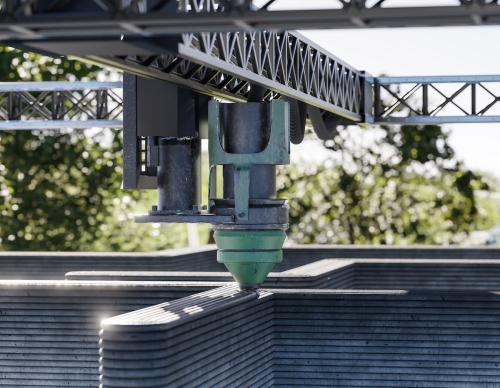

This is only the beginning. Drones are being incorporated into the arsenals of state and non-state actors across Africa and have been decisive in shaping battlefield outcomes in conflict theaters such as Libya. With the rise of additive manufacturing, drones and other technologies such as AI sensors, robots, and rockets are becoming cheaper. The prospect of affordable, widely available cutting-edge technology may allow some African states to build their own defense industries. A firm in South Africa, which has been manufacturing drones since the 1970s, recently announced its intention to build drone swarms “designed for technology transfer and portable manufacturing with partner countries.”

The ultimate impact of emerging technologies will depend largely on how governments choose to use them. Due to their low costs and rapid proliferation, AI and drones offer many African countries the opportunity to reap economic, political, and security benefits through early adoption. However, the impact of emerging technology could be destabilizing if used to enhance corporate profits and regime security without regard to the lives and livelihoods of ordinary citizens. While it is too early to tell where things are headed, the continent’s general trajectory, if there is one to be had, will be clearer in the aftermath of COVID-19.

COVID-19 and its aftermath

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to act as an accelerant for the spread of emerging technology. The pandemic has already led to remarkable innovation. According to a study by the World Health Organization, 13% of all new or modified technology developed to respond to COVID-19 is African. In Ghana, authorities launched a COVID-19 tracker app, citizens invented solar-powered hand-washing stations, and private sector Zipline drones delivered tests. In Tunisia, the Interior Ministry deployed a robot to help enforce a lockdown. When confronted by a man attempting to buy cigarettes, the robot relents: “OK buy your tobacco, but be quick and go home.”

But as life has moved increasingly online, opportunities for malicious actors to exploit digital technology have grown. Cyberattacks in countries across Africa have risen, with threat actors adopting techniques designed to exploit shifts to less secure home office work environments and other COVID-related fears. In Zimbabwe, cyberattacks increased by as much as fivefold during the pandemic, driven by phishing attacks that impersonate organizations working on pandemic response or use COVID as a lure to get unwitting individuals to download malicious software.

Moreover, Africa’s economies are expected to take significant time to recover from a pandemic-induced shock, leading to increases in poverty and declines in GDP that stand in sharp contrast to the first two decades of the twentieth century. As connectivity continues to rise, increases in poverty and inequality could herald an increase in the growth of cybercrime, as tech-savvy and college-educated Africans find opportunities for licit forms of employment limited. For example, SilverTerrier, a major cybercriminal actor based in Nigeria, is made up of individuals in their late teens through early forties, based in urban areas, and possess some level of post-secondary education, according to a study of the group.

The economic, political and technological shocks of COVID-19 could also accelerate unsettling trends of digital repression and conflict. Prior to the pandemic, conflict in Africa was already on the rise and democracy in retreat. Facing declining revenues and rising social unrest, it is probable that regimes will double down on surveillance, censorship, and disinformation rather than compromise or address the grievances of disaffected groups. In Uganda’s recent election, authorities hacked the encrypted communications of opposition leader Bobi Wine, ran a sophisticated online influence operation, and shut down the internet, efforts that helped to elect the strongman incumbent Yoweri Museveni to a sixth term.

A protean legacy

Most likely, African governments will continue to exhibit tremendous variation in their ability to adapt to this period of geopolitical uncertainty and technological change. Some of the more innovative countries may surf the spread of digital technology to prosperity and stability. Mauritius, Rwanda, and Kenya, for example, possess dynamic, tech-driven economies and are the only African countries to rank in the top 50 of the International Telecommunication’s Unions global cybersecurity commitment index.

More countries, however, risk being destabilized or limited in their ability to harvest the fruits of the digital revolution. Nigeria has more tech hubs than any other country in Africa, but has also become a global center for cybercrime. Libya’s information environment experienced a brief renaissance in the aftermath of the fall of Muammar Ghaddafi in 2011, but has since become a “fragmented vacuum,” controlled largely by armed groups and foreign actors. Internet connectivity is a basic prerequisite for technology-driven growth and innovation, yet in fifteen countries, penetration rates are ten percent or less.

For Africa’s digital revolution to yield peace and prosperity, it is not enough for African countries to focus on the rapid, and often reactive, adoption of emerging technology. It is equally crucial to consider risks and externalities. Increasing internet connectivity should be prioritized, but so should affordability, cybersecurity, and equitable access. Drones and artificial intelligence offer African countries profound opportunities to innovate, but could be destabilizing without strategies, policies and legal frameworks to govern their use. And, driven in part by the pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic, the question of what African governments should do to respond to the proliferation of emerging technology is no longer a theoretical one. It is urgent.

The signs of Africa’s digital revolution are impossible to miss. The destination? Impossible to know.

Nathaniel Allen is an assistant professor with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies at National Defense University and a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author.

Commentary

The promises and perils of Africa’s digital revolution

March 11, 2021