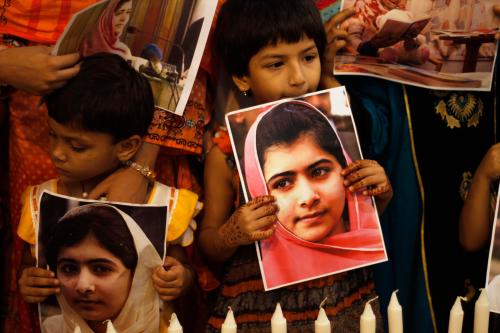

Within the education community, we often lament that we do not have the equivalent of a malaria net or polio vaccine that can rapidly focus policymakers on the task of getting all children into school and learning well. Yet, we may have finally found our answer in a 16-year-old Pakistani girl.

Malala Yousafzai has catapulted education onto the international stage. Since her brutal attack last October, she has spoken twice on the floor of the United Nations alongside U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, was featured on the cover of Time Magazine as one of the “The 100 Most Influential People in the World,” and was the recipient of Pakistan’s first National Youth Peace Prize and the 2013 Sakharov Prize. She has come to symbolize the reprehensible injustice that millions of children—and girls in particular—face in merely trying to exercise their basic human right to go to school. She represents the determination that so many children and young people demonstrate each and every day to overcome enormous barriers to attend school. In short, her eloquence and influence is a reminder to all of us of the transformative power of education.

In Pakistan, and in Malala’s home province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, attacks on girls are commonplace. Just last month, a bomb exploded near a girls’ school in northwestern Pakistan. Girls’ participation in school—along with learning levels for many who are able to participate– is still appallingly low, with 57 percent of children grade 5 or higher who still cannot read a grade 2 Urdu or Pashto story. However, since the global attention given to Malala’s plight, she has met with her own president (both after her attack and at the United Nations on “Malala Day”) to further the cause of girls’ education and advocate for improved conditions in Pakistan and for girls globally. In order to leverage the attention she has received and foster concrete support for girls’ education, Malala and her family have set up the Malala Fund, which aims to empower 600 million girls in developing countries with gender-focused approaches to education.

Today, however, the Nobel Peace Prize was not awarded to Malala. Regardless, this should not discourage us given the progress Malala has inspired and the work that still remains. In a year following her attack, Malala has not only garnered international attention and support for education but also gained popular support as a contender for the world’s highest honor for promoting peace among nations. Her recognition for this prestigious award signifies her impact and shows that the fight for girls’ education is nowhere near complete.

Malala’s work has just begun and, in many ways, demonstrates the potential for the international community to come together. Let us truly honor Malala, as well as the millions of other girls around the world who take enormous risks each day to get an education, by moving from words to action. We must ensure that all children—regardless of their sex, location or socio-economic status—are able to go to school, stay in school and learn something of value while there.

The global community faces a window of opportunity to translate the well-deserved attention bestowed upon Malala into real improvements in girls’ lives. We must seize the momentum created by Malala and take bold action to get more girls into primary and secondary school and ensure that they are learning.

[1] We owe it to Malala and the more than 65 million girls who remain out of primary and lower secondary school. Malala joins a host of established leaders (including Hillary Clinton, among others) who have championed this message and urged us to promote opportunity for girls globally. To move from celebrating Malala’s achievements to affecting real change in girls’ lives, there are three specific areas that we must focus on:

Ensure that girls get an early start on learning.

In those countries that are the furthest from achieving gender parity in primary school, the main obstacle for girls is that they are not entering school in the first place; this is a key reason for lower enrollment of girls. [2] Changing this reality will require that we ensure the availability of safe, quality early childhood programs that prepare young girls for school. Despite the fact that evidence shows that early childhood education increases overall retention, reduces drop outs and raises completion rates in primary school, less than half of all children in developing countries attend any pre-primary school—with this number dropping to 15 percent in low-income countries. [3]

Ensure that girls not only go to school, but stay in school and learn while there.

While an increasing number of girls are now starting primary school, a much smaller number are able to complete a full cycle. In low-income countries, slightly more than one-half of girls who enter primary school make it to the last grade. [4] Investments must be made to ensure that girls not only have access to primary school, but complete a full cycle of good quality schooling that builds foundational academic skills in reading, writing and math, as well as non-cognitive skills such as critical thinking, communications and negotiation skills.

Ensure that girls transition to—and complete—relevant secondary education.

Finally, it is imperative that girls’ education does not end after primary school. Rather, they must be able to make the transition to (and complete) secondary schooling that teaches them the relevant academic, vocational and transferable skills needed to thrive in the 21st century. This is particularly crucial for poor girls, given the high social and economic returns of secondary education for these girls and their families. In Malala’s home country of Pakistan, 26 percent of girls still fail to continue on to secondary school. While there is a lot that we already know about effective strategies for helping girls continue onto and remain in secondary school, critical knowledge gaps remain. We must build upon the evidence base at the secondary level, specifically around how to reach the most marginalized children and young people; how teaching practices affect learning outcomes for children of both genders; and how to scale up and sustain effective interventions to reach many more girls and boys.

[1] UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). 2013. Database. Montreal.

[2] UNESCO, EFA Global Monitoring Report 2012: Youth and Skills: Putting Education to Work.

[3] UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). 2012. Database. Montreal. Enrolment ratios in the table are based on the United Nations Population Division estimates, revision 2010 (United Nations, 2011), median variant.

[4] UNESCO, EFA Global Monitoring Report 2012: Youth and Skills: Putting Education to Work. Table 6 in Annex. Statistics in table taken from: UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics). 2012. Database. Montreal.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Nobel Peace Prize Announcement: Why the Education Community Should Not be Discouraged

October 11, 2013