A version of this article originally appeared in MarketWatch on May 27, 2019 and the Wall Street Journal on June 3, 2019.

“Eventually, I’ll stop working.” Most of us think that and know it will happen, but millions of us worry whether we’re saving enough to live on once we do. We want to know: How much of my earnings should I set aside? What’s the magic number? 3%? 5%? 10%? More?

What your financial adviser won’t tell you:

Unfortunately, the retirement industry has spent decades largely avoiding the magic-number question. “There’s no magic number for everyone,” some say. “It’s complicated,” say others. And then they offer, sometimes for a fee and sometimes for “free,” to take our money and invest it for us — often without telling us whether it’ll be enough when the time comes.

Why will no one give us a magic number? They don’t want to be legally responsible when the number turns out to be too low, which, for some of us — especially those whose pay is low or whose investments are poor or who live long and need a nursing home for years — it will. The legal jitters are understandable, but they leave us in the dark about how much to save.

Don’t give up hope. There’s research that can help — from institutions that don’t have a conflict of interest because they don’t invest or give advice. My favorite is the Employee Benefits Research Institute in Washington, D.C. EBRI, as it’s called, gathered anonymous information on tens of millions of people and how they actually save. It won’t tell people what to do, but – for millennials – there’s a pretty useful rule of thumb from its research: Count on your fingers and …

Save 10% — now

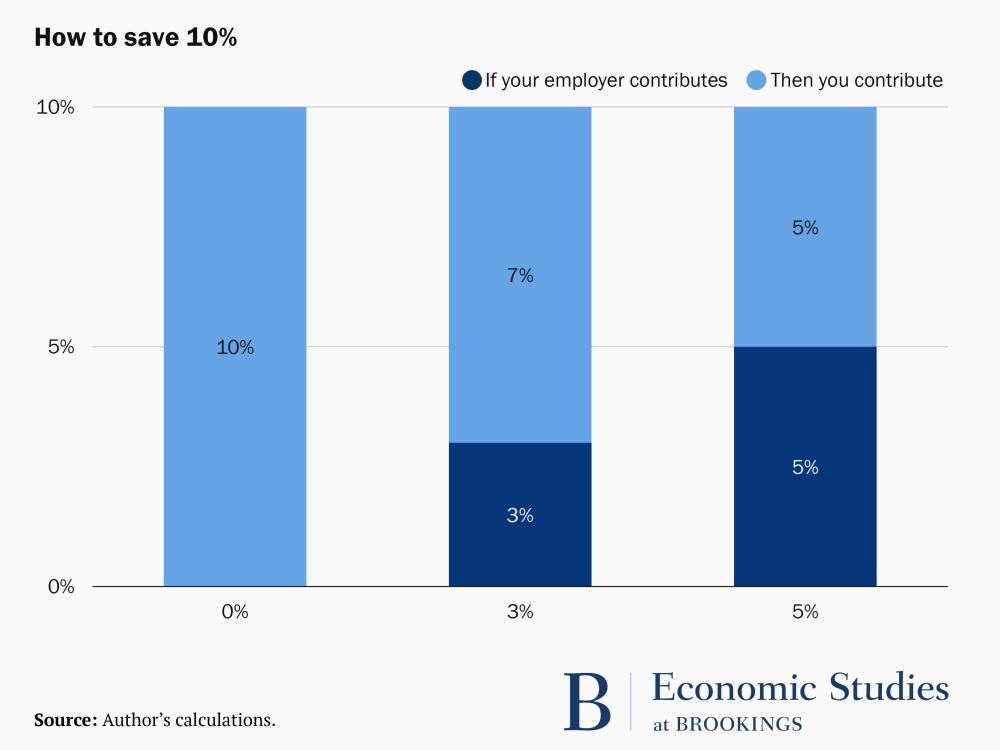

Between you and your employer, set aside at least 10% of your paycheck. If your employer contributes 3%, then your share is at least 7%. If the company kicks in 5%, then you save at least 5%. If your employer does nothing, set aside at least 10% of each paycheck on your own. (If you are older and haven’t started retirement saving, then 10% will be too low: start thinking at least 15%-20%.)

Of course, there will be times when you’re between jobs or you need your money for a pre-retirement-age emergency. In those cases, you can put your money in a Roth individual retirement account (IRA) account. That way, you can take your contributions out without penalty. (There are also Roth 401(k) accounts, though they have more complicated withdrawal rules.) Don’t let the fact that you might need money someday keep you from saving for retirement now.

It’s perfectly OK to consult a financial adviser and get more personalized recommendations, but if you can’t or don’t want to — or while you’re waiting to “get around to it” — set aside enough so that, together with your employer match, you’re putting aside at least 10%.

America’s No. 1 fear: golden years minus the gold

People are living longer. That’s both good news and bad: We hear about baby boomers moving into posh “active adult” communities, but we also hear about disabled and bedridden elderly requiring years’ worth of health aides and the constant help of their children. Either way, longer lives seem expensive.

And our capacity to lay the groundwork for retirement can feel pinched from all directions. Life can be expensive even in our earning years, with college tuition, housing and medical costs in the stratosphere. Student loans and credit-card debt intrude. Social Security, we’re told, is at risk. Lifetime pensions are, for most, a thing of the mythical past. All that most of us feel we can count on is a retirement account that’s at the mercy of the markets and, we suspect, doesn’t have enough in it. Many, of course, don’t even have that.

Experts often tell us how complicated this is to figure out — and why we should hire them to do it for us. And it is easy to make it complicated: We can try to decide — now, decades before we’re ready to even think about retiring — what our future earnings will be and how long we’ll work, what lifestyle we’d prefer in retirement, how much health care will cost decades down the road, how long we’ll live after retirement (with a margin for error, of course), how our money should be invested and what our investment returns will be (with, again, a margin for error). Not complicated enough? Add whether or not we’ll need funds at hand to support children or parents or other family members.

The result is confusion. Some people get financial advice. Others turn to online retirement calculators. Many, sadly, do nothing at all, falling back on a vow of resignation: “I’ll just keep working.” (Spoiler: Almost no one who says they’ll work until they die ends up doing so.) For still others, it means saving too little.

Modeling for millennials

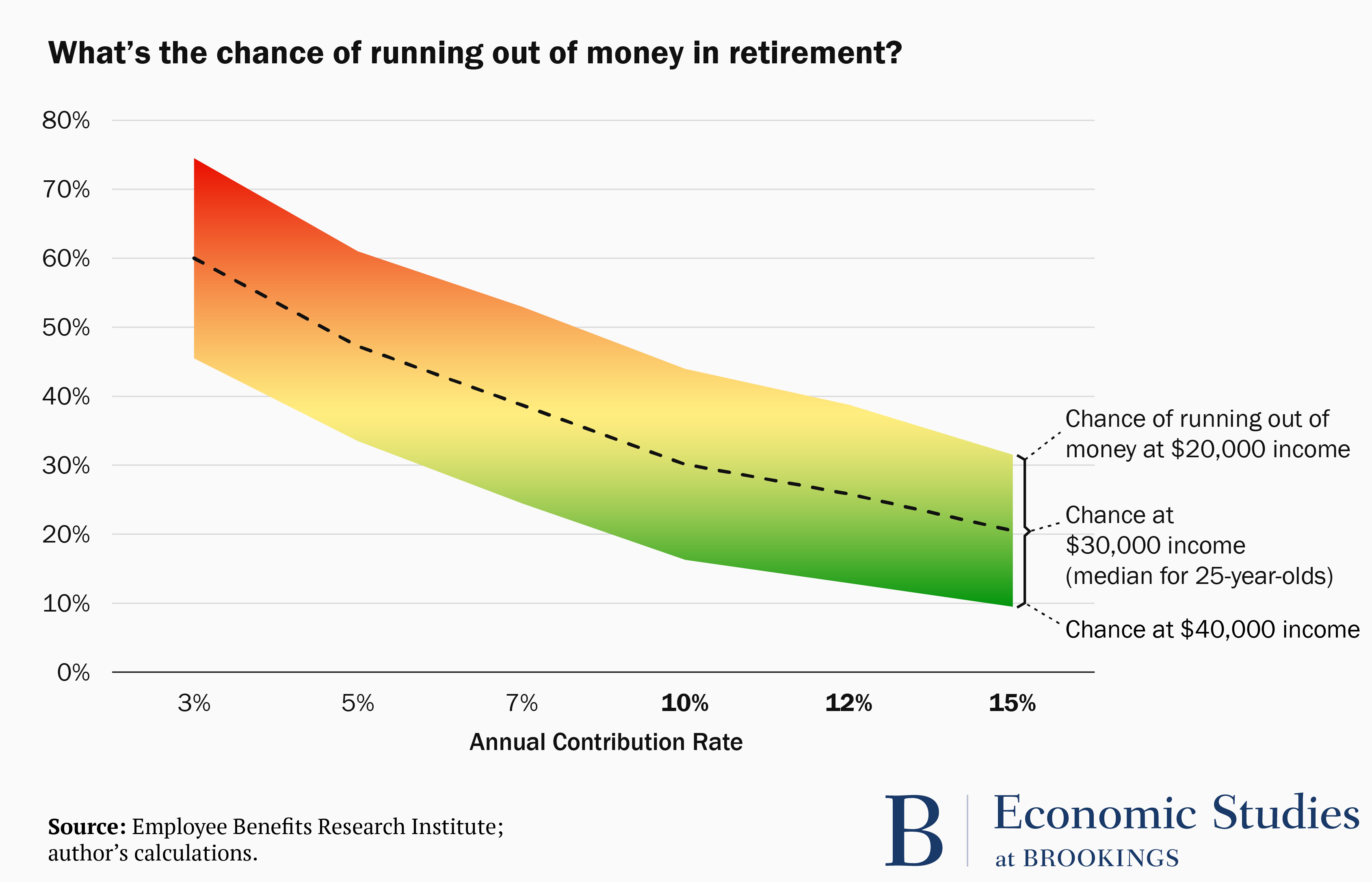

How can EBRI’s model help? It estimates the risk of running out of money after retirement by taking into account many more factors than the usual online calculator: contributions, market changes, Social Security benefits and salary growth, as well as a range of health outcomes and longevity prospects. It can then estimate the risk that — for particular savings rates and income levels — a person’s expenses in retirement will overwhelm their savings plus Social Security benefits.

For this article, EBRI provided projections for today’s 25-year-olds at multiple income levels; we’ll interpolate the results to reflect the median income of today’s 25-year-olds, which is $30,000. (The projections assume that people will earn more as they get older.)

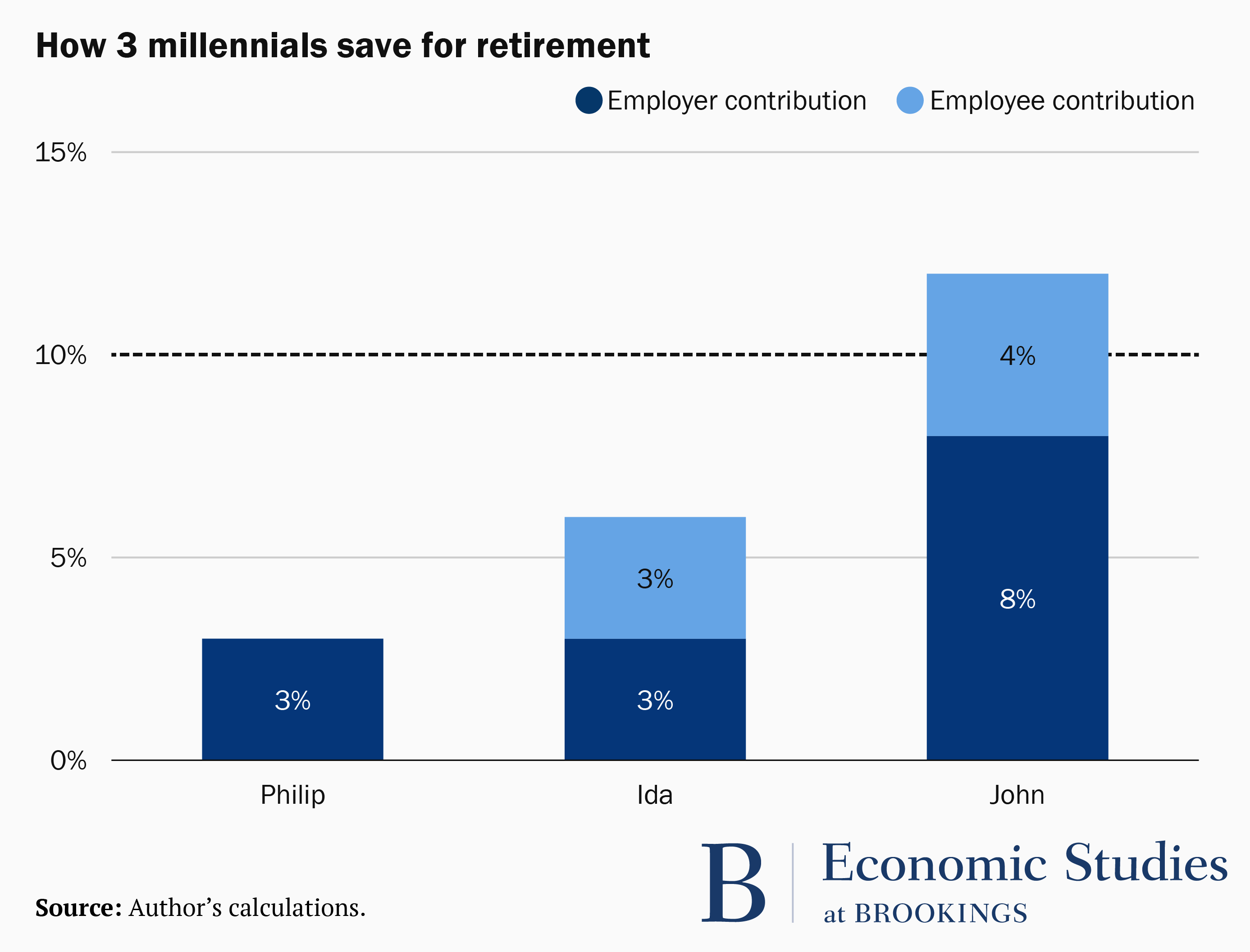

We then applied EBRI’s projections to three millennials. Their names have been changed, but they are all in their mid-20s. We’ll assume they’re average earners:

- Phillip, working in a startup, contributes 3% of pay to a retirement account. His employer contributes nothing.

- Ida, an office worker, contributes 3%, which her employer matches, for a total of 6%.

- John, working for a financial firm, contributes 8%. His employer contributes 4%, for a total of 12%.

Are they contributing enough, too much or too little? Here’s how, based on EBRI’s model, our millennials and their different savings practices would end up at retirement:

- If Phillip, from a current salary of $30,000, continues to contribute just 3%, he has a 56% chance of running through both his retirement savings and Social Security in his lifetime. (If he were earning $40,000 now, the odds improve, but his chance of running out of money still exceeds 40%.) Clearly, then, 3% isn’t enough.

- Ida, being a woman, will likely live longer, so her 6% total contribution will have to last longer, and the probability that neither it nor Social Security will be enough is 47%. Sounds like 6% is too low, as well.

- John, contributing 12% of pay, has less than one chance in four (23%) of running out of money.

Overall, the EBRI simulation model suggests that, in the income ranges of most millennials, a contribution rate of 10% starting in a worker’s mid-20s cuts the risk of running out of money in retirement to about 30%, less than one chance in three. Contributing more than 10% when you can will give you a better cushion.

Of course, everyone’s situation is and will be different, so 10% is a guideline, not a guarantee. (Furthermore, if you start later in life, 10% won’t be nearly enough.)

Digital piggy banks

By now you’re probably thinking, “This is easier said than done.” And you’re right. Saving for retirement is like dieting in that we’re better at making resolutions and excuses than making progress.

But technology makes the savings part easier, too. More and more employer plans will sign you up automatically. If your employer doesn’t have a plan, you can set up a Roth IRA with a bank or an investment company and have a portion of each paycheck deposited automatically. Some states, including Oregon, Illinois, California and Maryland (whose program I chair), are setting up IRA programs for small businesses that don’t offer retirement plans.

The good news is that, in one respect, retirement saving is easier than dieting: If you fall off the wagon, you can start again and feel better immediately.

Yes, life is complicated. Retirement plans don’t always turn out as planned. But if, while worrying about everything else, we each adhered to the 10% rule as much as we are able, there would be a lot less retirement insecurity and a lot more gold in the golden years.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edThe new math of saving for retirement may boil down to this one, absurdly simple rule

June 5, 2019