The APEC Leaders’ summit meeting, which took place last week in Danang, Vietnam, crystallized the new geopolitics of trade in Asia. The leaders of the three largest economies in the world—the United States, China, and Japan—each redefined the roles their nation will play in sustaining, torpedoing, or adjusting the postwar trading order. Little is assured on how free trade and multilateral undertakings will fare as the three giants reposition themselves in their leadership bid. The only certainty ahead for us is that it will be a bumpy ride.

“America First” FLounders

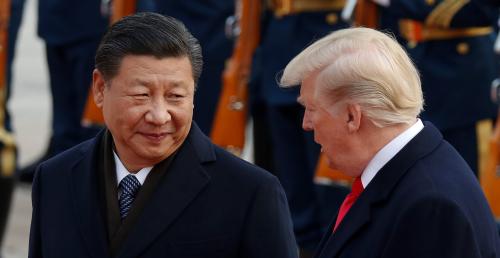

Trade figured prominently in all of President Trump’s stops during his first official visit to Asia. But the full-throated articulation of his “America First” trade policy was delivered in his speech for APEC’s (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) CEO summit. To a forum whose mission is to promote closer economic links among 21 member economies, President Trump confirmed that under his watch, the United States will not ink any regional or multi-party trade agreement because—he argued—these agreements unduly tie the hands of the United States. The president roundly criticized the World Trade Organization, stating it treats the United States unfairly, and warned that rampant cheating by others (reflected in U.S. trade deficits) will no longer be tolerated. Jaws surely dropped when Trump placed the blame not on the cheaters (who, after all, the president noted, were just looking after their citizens in taking advantage of the United States on trade) but on all previous U.S. governments.

In the more evocative part of his speech, the president spoke of an Indo-Pacific dream built upon a series of bilateral trade agreements that the United States stands ready to negotiate with nations willing to embrace fair and reciprocal trade. By and large, this is a dream of one: No Indo-Pacific nation (with the potential exemption of Philippines) has accepted the entreaty to negotiate bilaterally. Two powerful deterrents to countries signing on to Trump’s proposal are at work here: 1) countries see through the faulty proposition that trade deficits driven by macroeconomic forces can be wiped out quickly with trade negotiations, and 2) widespread understanding that multilateral deals promise larger economic gains by turbocharging global supply chains.

President Xi moved once again to occupy, rhetorically, the space the United States vacated as champion of multilateralism and free trade.

President Xi moved once again to occupy, rhetorically, the space the United States vacated as champion of multilateralism and free trade. Addressing the same audience right after President Trump, he delivered a starkly different message. He defended the value of international trade as a win-win proposition and tool for development, and portrayed globalization as an unstoppable yet moldable force that could be more inclusive and balanced. Without question, China’s economic and political influence has expanded significantly with the successful launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative. Through these initiatives, China is recycling capital surpluses to finance infrastructure in developing Asia with improvements to regional connectivity. But leadership in free trade may be China’s last frontier because it hinges on the supply of a commodity in short supply in Xi’s vision for China: liberalization. The 19th Party Congress did not set China on a path to become a free trader. On the contrary, it confirmed that the impetus for meaningful domestic reform has waned and the state’s role in the economy is the North Star.

TPP, back from the dead?

The high drama at APEC’s meeting came not courtesy of dueling American and Chinese scorecards on globalization but of the ups-and-downs in efforts led by Japan to resurrect the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade pact. Tensions were high when Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada did not attend the TPP 11 summit meeting, where leaders had already gathered to give their seal of approval to a broad agreement. A frenzy of last-minute negotiations ensued, and it was ultimately possible to reach an agreement on the core elements of a newly baptized Comprehensive and Progressive TPP (aka TPP 2.0).

In so doing, the 11 remaining nations achieved a remarkable feat: They maintained market access commitments intact with tariff liberalization to proceed as originally scheduled, and they limited the disciplines to be suspended (until and if the United States returns) to a list of 20. The thrust of these suspensions is to narrow down the operation of investor-state dispute settlement (by extracting investment agreements and investment authorizations) and to freeze the intellectual property rules the United States had advocated (on data protection for biologics, copyright extension, and the scope of patentability, for example). No sledgehammer was used to scrap entire chapters; on the contrary, the outcomes reveal a surgical approach to keep the agreement whole and maintain the level of ambition.

The TPP 2.0 is far from a done deal. The ministerial statement listed four pending issues: a cultural reservation for Canada, Malaysia’s schedule on state-owned enterprises, a coal non-conforming measure for Brunei, and one article on trade sanctions for Vietnam. None of these appear to be insurmountable obstacles, but, although not listed in the ministerial statement, Canada has insisted on renegotiating auto rules of origin. In this way, Canada has emerged as the wild card in the final stretch for this trade deal.

Shifts among the heavy hitters

The geopolitics of trade in Asia are in flux as the three major powers transition to new roles. A United States critical of multilateral and regional undertakings, unable to gain traction in bilateral trade negotiations, and eager to resort to unilateral enforcement as the main thrust of trade policy. A China that is knitting the region together through infrastructure finance and has vied for the title of champion of multilateralism, but comes woefully short in the supply of liberalization. And a Japan that is cutting its teeth in trade leadership by rescuing the TPP project, not out of a desire to displace the United States from its traditional role in regional economic diplomacy but instead to encourage its return.

Japan’s leadership credentials will be greatly enhanced if it is able to successfully conclude negotiations among the diverse set of TPP nations to keep the highly ambitious trade agreement intact, even though the original magnet (the U.S. economic and security heft) is not at play for the foreseeable future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The new geopolitics of trade in Asia

November 15, 2017