China’s leaders have staked the country’s future on innovation. In its latest blueprint for national economic development, China has pledged to end its reliance on imported technology and to focus on domestic consumption as the primary driver of growth. At a conference in May for engineers and scientists, Chinese leader Xi Jinping urged greater self-reliance in science and technology, which would serve, he said, as “the strategic support for national development.”

China’s drive toward technological independence has raised alarm bells in the West, where a resurgent China powered by a leading technology industry is widely considered the key strategic challenge of the 21st century. But these fears all too often fail to consider the internal obstacles facing Beijing’s push toward tech supremacy. Among them is one very low-tech problem: a prevailing sense of social and professional stagnation.

The drive toward self-reliance has encountered an unlikely form of resistance in a generation of young Chinese who balk at the Party’s high-minded calls for “continued struggle” alongside an deeply engrained culture of overwork without the promise of real advancement. They opt instead for “lying flat,” or tangping (躺平). The “lying flat” movement calls on young workers and professionals, including the middle-class Chinese who are to be the engine of Xi Jinping’s domestic boom, to opt out of the struggle for workplace success, and to reject the promise of consumer fulfilment. For some, “lying flat” promises release from the crush of life and work in a fast-paced society and technology sector where competition is unrelenting. For China’s leadership, however, this movement of passive resistance to the national drive for development is a worrying trend—a threat to ambition at a time when Xi Jinping has made grand ambition the zeitgeist of his so-called “New Era.”

‘Lying flat is justice’

The “lying flat” movement was jumpstarted in April when a post on Baidu titled “Lying Flat Is Justice” went viral on the platform. A manifesto of renunciation, the post shared the author’s lessons from two years of joblessness. The extraordinary stresses of contemporary life, the author concluded, were unnecessary, the product of the old-fashioned mindset of the previous generation. It was possible, even desirable, he argued, to find independence in resignation: “I can be like Diogenes, who sleeps in his own barrel taking in the sun.” Discussions about “lying flat” picked up pace in May, as young Chinese, over-worked and over-stressed, weighed the merits of relinquishing ambition, spurning effort, and refusing to bear hardship.

On May 20, the Party-state media issued a series of simultaneous rebuttals. “The creative contribution of our youth is indispensable to achieving the goal of high-quality development,” Wang Xingyu, an official at the China University of Labor Relations wrote in the Guangming Daily. “Attending to those ‘lying flat,’ and giving them the will to struggle, is a prime necessity for our country as it faces the task of transitioning development.” Nanfang Daily, the mouthpiece of Guangdong’s CCP leadership, ran a page-four commentary expressing disgust over the notion of “lying flat,” concerned that talk of resignation might become a self-fulfilled prophecy. “At any time, no matter what stage of development, struggle is always the brightest base color of youth,” it said. “In the face of pressure, choosing to ‘lie flat’ is not only unjust, but shameful. There is no value whatsoever in this poisonous chicken soup.” In a video that made the rounds online the same day, a commentator at the official Hubei Economic Television said in an admonishing tone: “To accept misfortune is fine, but ‘lying flat’ is not.” This condescension was widely ridiculed across Chinese social media.

As state media made their position clear, the original April post on “lying flat” suddenly disappeared. The search function for “lying flat” on WeChat, where the word had still been trending, was disabled. On the Douban social networking service, a “lying flat” discussion group was also shut down. And on Taobao, the popular online shopping platform run by tech giant Alibaba, t-shirts related to “lying down” were pulled from online stores.

The social cost of innovation

Over the past decade, China’s leadership has identified innovation as the way forward for economic and social development. The promise of innovation has been epitomized by China’s tech entrepreneurs, including billionaire founders like Alibaba’s Jack Ma and Tencent’s Pony Ma. But the dream of innovation has collided with the harsh reality of overwork in a technology sector that seems sapped of opportunities for breakthrough. Jack Ma and others have advocated a severe culture of overtime work that has become known as “996”—working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week. At the technology giant Huawei, this extreme work environment has been dubbed “wolf culture,” a climate of fierce internal workplace competition in which workers must either kill or be killed. Observers have drawn a straight line from “996” culture to the “lying flat” movement. “Lying flat was spawned under the persecution of the 996 overtime culture,” one writer argued on the Zhihu platform. “We employees are too tired. We have to lie down and rest.”

The “lying flat” movement isn’t the first time China’s tech workers have rebelled. In 2019, thousands of tech workers, including programmers and beta testers for major technology firms, responded to China’s extreme working conditions by launching an online campaign called “996.ICU”—a mashup of “996 culture” and “intensive care unit” referencing instances of programmers seeking emergency medical treatment for work-related health crises. “996.ICU” began compiling a list of Chinese companies with extreme work cultures and advocated an industry consensus on reasonable hours.

While the campaign managed to focus some attention on the issue of extreme overwork, it could not shake the predominant culture in China’s tech industry. Company bosses merely shrugged it off. Confronted with questions about “996” at a meeting that year, Jack Ma said, “In this world, all of us want to be successful, all of us want a good life, and all of us want to be respected. I ask you, ‘How can you achieve the success you want if you don’t put in more effort and time than others?’” In a post to Alibaba’s WeChat account, Ma called the company’s work culture a “huge blessing.”

Chinese tech executives’ embrace of extreme work culture find justification in the official Party narrative of tireless struggle in the service of China’s global rise. But try as it might to drown out the growing despair among millennials and Generation Z, China’s government will have to grapple with the social costs of breakneck competition in an environment of dwindling returns. And it will have to do more than repeat slogans of struggle and self-sacrifice to inspire the next generation of workers and innovators.

Consumer remorse

For China’s young workers, the pressure to forge ahead and innovate is compounded by the pressure to consume. Before the new millennium, Chinese were culturally savers, and consuming on credit was exceptionally rare. It was generally supposed that conspicuous consumption was something unsuited to China’s national conditions. Over the past decade, however, these assumptions have been turned upside-down. Chinese can now be counted among the world’s most conspicuous consumers.

The consumer boom has been fueled by government policies to encourage domestic consumption. Just eight years ago, in 2013, the government introduced consumer finance pilot programs that encouraged easy credit. These programs came alongside a tech-driven revolution in consumer payment, including the launch in 2013 of WeChat Pay, a digital wallet service connected to the all-purpose social media super-app that enabled users not just to make mobile payments but to transfer money to their contacts. By 2016 in China, barcode payment had been completely normalized, transforming mobile phones into virtual wallets. By 2019, the new trend was to link payment with facial recognition technology.

Fueled by technology and cheap credit, online shopping has exploded in China in recent years. During last year’s Single’s Day shopping event, e-commerce giants including Alibaba and JD.com made $115 billion in sales. Alibaba’s sales alone doubled over the previous year. During the recent “618” online shopping event, total sales turnover on major Chinese e-commerce platforms reached nearly $90 billion, up more than 26% over 2020. (By comparison, independent sellers on Amazon took in $4.8 billion between Black Friday and Cyber Monday last year.)

Along with innovation, consumption is the second leg on which China’s economic future is to stand. It was a telling fact last year when China’s Premier, Li Keqiang, refrained from talking about GDP in his annual government work report, focusing instead on consumption. In a press conference after the release of the report, Li said that “consumption is now the primary engine driving growth” and indicated that the bulk of government stimulus funds would be applied “to support the increase in people’s income through direct or relatively direct means in order to spur consumption and energize the market.”

But as consumption has become a perceived necessity, a form of psychological reprieve from the pressures of work, and even a patriotic duty, some young Chinese have buckled under the immense pressure to keep up. Consumer debt has grown dramatically in China during Xi Jinping’s “New Era,” in what one business analyst has called “an unfolding debt crisis.” The problems facing young borrowers, who have increasingly turned to online consumer finance providers, prompted Chinese regulators to issue a ban in March on new consumer loans to college students, who have frequently been targeted by providers with loans at interest rates sometimes nearly double the 24% allowed by regulations. Skyrocketing living costs in China’s cities have also meant that many young Chinese, even with elite college degrees, find it difficult to cover the basics, much less afford a life of conspicuous consumption.

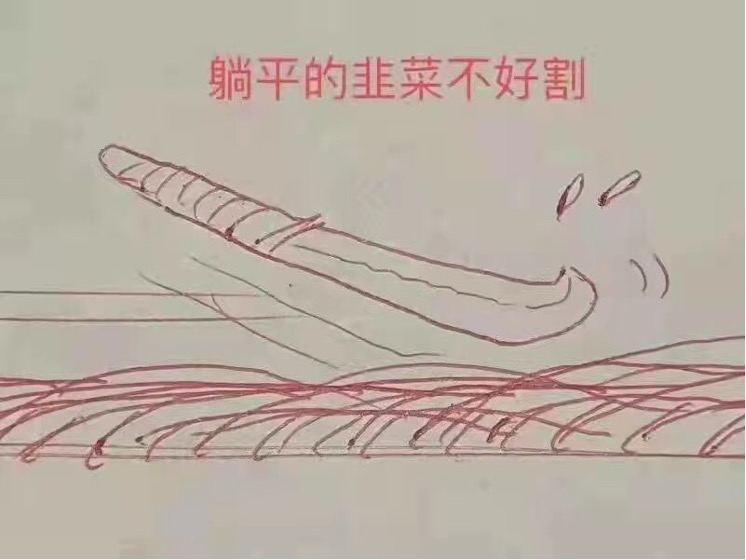

For young people struggling under the weight of both extreme competition and its would-be reward, the empty promise of consumerism, it can seem that there is no escape from exploitation. And in a society where more open forms of protest, such as labor activism, are quickly suppressed, they have found release, if not relief, in online expression. The “lying flat” movement, whose forums have drawn upwards of 200,000 members, is one example of this, and a slew of popular online terms have emerged to describe the sense of hopelessness. These include “leek people” and “harvesting leeks,” phrases that liken those caught in the struggle of work and consumption to leeks that are constantly harvested under the blade. “Lying flat-ism,” one Chinese journalist wrote on the Weibo platform, “is a non-violent movement of non-cooperation by the leek people, and the most silent and helpless of actions.” When one opts out of the cycle, or so the reasoning goes, it is no longer possible to be cut down, as the illustration below, appearing on Chinese social media in May, expresses. A harvest knife slashes vainly in the air as the plants below fold themselves down toward the earth. “Leeks that lie down cannot be harvested so easily,” the caption reads.

“Lying flat-ism” is seen by some as the only possible form of resistance to this cycle of exploitation. One of the dominant slogans of the “lying flat” movement has been, “Don’t buy property; don’t buy a car; don’t get married; don’t have children; and don’t consume.” For this reason, calls to “lie flat” have doubly concerned China’s leadership, as they threaten both to sap the country of the ambition to innovate and to knock down the second leg of the country’s long-term development strategy—the drive to consume.

Rejuvenation, great and small

One lesson to emerge from the recent wave of attention to “lying flat” is that there are societal limits to the power of the Party-state to generate economic vibrancy and technological innovation through campaign-style approaches. These limitations can be overlooked or underestimated by the policy community in the West, as the dominance of the Party and the weakness of civil society encourages the perception of a monolithic command state capable of fulfilling its own policy wishes.

But even if they cannot be expressed openly as constraints on policy, the wishes of the Chinese people remain an important factor—and the “lying flat” movement makes this clear. More Chinese hunger for basic dignity. In China’s current political climate, however, dignity is something abstract, imagined only for the “Chinese nation” as it rises above the indignities of the 19th and 20th centuries to regain its rightful place in the 21st. In an April speech delivered shortly before the “Lying Flat Is Justice” post went viral, Xi Jinping encouraged the youth of China to “constantly strive for the Chinese dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

For many of China’s young workers, struggling through a twelve-hour workday and bracing for the next loan payment, such sloganeering about rejuvenation may sound detached from the personal hope for renewal—for better pay, better working conditions and protections, and for more security. With or without anti-slogans like “lying flat,” the attitudes of China’s white-collar workers seem to be changing. A recent survey by Zhao pin, a leading career platform in China, found that more than 80% of white-collar respondents cited fair treatment and respect by companies as the most important factor in company cultures. Workers generally rejected “996” and “wolf culture,” hoping instead for more balance and humanity.

In Xi’s China, however, where the Party and the state reign supreme, it has become virtually impossible to stand up for one’s own rights and interests—to assert one’s personal needs and desires over the grandiose ambitions of the national self. “Lying flat” is an answer, passive and desperate, to the dehumanizing nature of the struggle, both national and personal. Why should one stand for self-reliance, only to be cut down and harvested?

David Bandurski is the co-director of the China Media Project, a research program in partnership with the Journalism & Media Studies Center at the University of Hong Kong.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The ‘lying flat’ movement standing in the way of China’s innovation drive

July 8, 2021