This explainer was originally published in August 2017 and has been updated several times since.

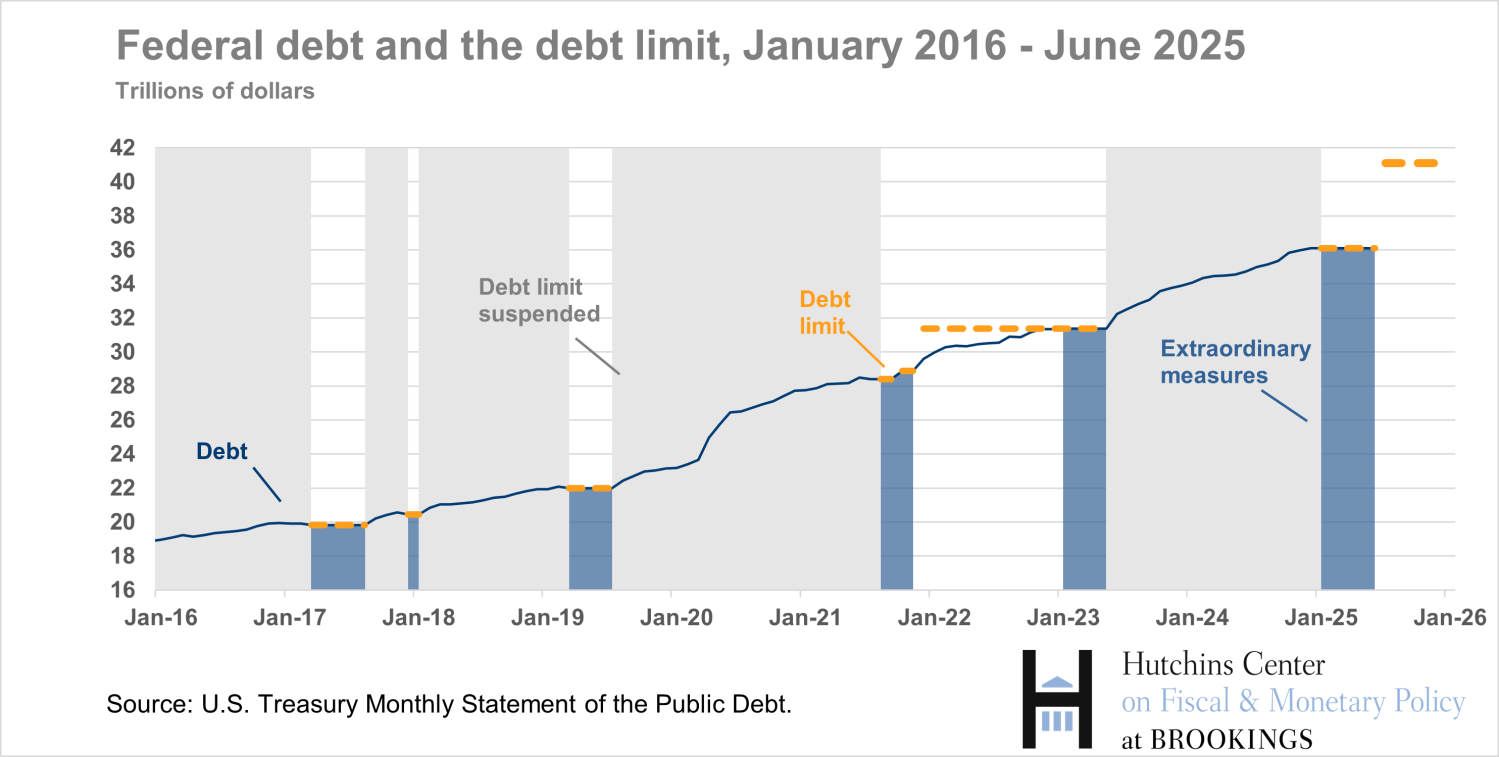

The recurring need to lift the ceiling on overall U.S. Treasury borrowing is always a political hot potato. The U.S. government’s borrowing hit the debt limit ($36.1 trillion) on January 1, 2025. The Treasury then initiated what are known as “extraordinary measures” to conserve cash. On May 9, 2025, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent told Congress that unless Congress acted, the Treasury probably wouldn’t be able to pay its bills in full and on time beginning in August. Congress did act. In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law in July 2025, Congress raised the debt ceiling by $5 trillion, to $41.1 trillion, which probably will delay another debt-ceiling showdown for a year or two. (The tax and spending provisions of that bill will add an estimated $3.4 trillion to the federal debt over the next decade before counting added interest costs, according to the Congressional Budget Office.)

What is the debt limit, and why do we have one?

When the federal government runs a deficit—that is, spends more than it collects in revenue—it borrows money to cover the difference, usually by issuing IOUs in the form of U.S. Treasury securities. The debt ceiling is a legal limit on the amount of borrowing the Treasury can do.

Before 1917, each loan issued by the Treasury required authorization from Congress. When the U.S. entered World War I, however, Congress changed the law to allow the Treasury to sell war bonds (Liberty Bonds) as needed, provided that bond sales didn’t exceed a specific amount—the debt limit.

Over the last three decades, the limit has precipitated political battles during which some legislators have used the vote on the debt ceiling to try to slow the growth of federal spending. In 2011, for instance, an impasse was resolved when President Obama and Congress agreed on the Budget Control Act, which raised the debt ceiling and set limits on future spending.

When Congress is faced with a decision about the debt ceiling, it can either choose to raise the debt ceiling by a fixed dollar amount or to suspend the debt limit for a specified period of time. When Congress raises the debt ceiling, the Treasury can continue to issue debt as needed until it reaches the new debt level. For example, in December 2021, Congress raised the debt ceiling from $28.9 trillion to $31.4 trillion, allowing borrowing to proceed until the total government borrowing reached this new limit (which finally happened on January 19, 2023). On the other hand, when a suspension period ends, the debt limit is reinstated at a level that accommodates the federal borrowing that has occurred up until then. For example, in August 2019, the debt ceiling, then at $22.0 trillion, was suspended for 24 months. During this period, the Treasury borrowed an additional $6.4 trillion. When the suspension period expired in August 2021, the debt limit was reinstated at $28.4 trillion—the sum of the previous limit and the additional borrowing.

After a debt limit is reached or a debt suspension period ends, the U.S. Treasury is no longer authorized to borrow additional funds. At that point, the Treasury can and often does take what are known as “extraordinary measures” (explained below) to keep the debt subject to the limit from rising until Congress acts.

The most recent round of extraordinary measures began in January 2025, when the debt ceiling of $31.4 trillion was reached. With mere days remaining before the projected X-date—the day that even extraordinary measures would not provide enough cash for the government’s activities—the White House and Congress cut a deal. The debt limit was suspended until January 1, 2025. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen informed Congress that a new debt limit would be set on January 2 at the level of the debt outstanding the day before. But the debt was projected to decrease temporarily on that date, so she said Treasury anticipated that it would delay implementing extraordinary measures until sometime between January 14 and January 23, 2025. In a January 17 follow-up letter to Congress, Secretary Yellen announced that extraordinary measures would begin January 21, 2025, and “will continue to be evaluated on an ongoing basis.”

Does raising the debt ceiling allow the government to spend more money?

Raising the limit does not authorize the government to increase spending beyond the level Congress has approved. Rather, it allows the government to meet its existing obligations to citizens, vendors, and bondholders.

What happens when Treasury hits the debt ceiling?

First, the Treasury employs a series of cash-saving tools known as “extraordinary measures.” These maneuvers suppress the level of intragovernmental debt (Treasury securities held by other government agencies) to create space for public debt. One way to achieve this is by suspending the daily reinvestment of certain government funds. When the federal government sets up a fund—for retirement plans, currency exchange, or other government transactions—it invests a portion of that fund in special Treasury securities that mature and are reinvested daily. Preventing that reinvestment lowers Treasury’s total amount of debt and allows it to legally issue debt to the public once again. In August 2021, for example, the Treasury reported that suspending reinvestment of the G Fund (a retirement fund for Federal employees with a portfolio of U.S. Treasury securities) could free up $270 billion in debt which the Treasury could use to raise cash and pay bills. In the ensuing period of extraordinary measures, it borrowed $262 billion from the G Fund, which was paid back in full in December 2021.

Extraordinary measures buy time but aren’t large enough to prevent the government from reaching the debt ceiling eventually. Unless Congress raises the debt limit, these extraordinary measures will generate enough cash for a limited time, at which point the U.S. government’s ability to pay its bills will be limited by the amount of revenue it collects each day. The date on which the government won’t have enough cash to meet its obligations is hard to predict precisely because it depends on the flow of revenues and spending, which depend, among other things, on the pace of economic growth.

The blue line in the above chart shows the federal debt subject to the limit. Congress has suspended the debt limit five times since January 2016 (the periods shaded in gray). At the end of the suspension period, the limit is reinstated at a level that covers all borrowing during the suspension period—but the Treasury must undertake “extraordinary measures” (the periods shaded in blue) to prevent additional borrowing until Congress raises or suspends the limit once more. More recently, Congress raised the debt limit instead of suspending it: after extraordinary measures were used through mid-December 2021, Congress raised the debt limit (the dashed orange line) rather than entering another suspension period. A debt limit suspension was in place until January 1, 2025. The Treasury resorted again to extraordinary measures in January 2025.

What does it mean for the Treasury to run out of cash?

Every day, the Treasury collects revenues from taxes and pays its bills—everything from Social Security benefits to utilities in federal buildings to interest on the debt. When expenses exceed revenues, and the Treasury cannot increase its borrowing because of the debt ceiling, it can cover expenses only to the extent that there is cash coming in. There will be enough money coming into the Treasury to pay some—but not all—of the government’s bills and obligations.

Why is raising the debt ceiling so controversial?

The debt limit—although technically unrelated to the level of government spending—has become a flash point for debate about the size of the federal budget. Politicians who want to reduce deficits or restrain the size of government have used the debt limit to negotiate for spending caps or budget restrictions in the past—a tactic that has proven successful on occasion, as it was in 2011.

Some view “fiscal brinksmanship” as irresponsible and argue that raising the limit ought to be routine. Congress has already lifted, temporarily extended, or revised the definition of the limit 78 times since 1960, the Treasury says, and ought to do so again. Others, including a number of former Treasury secretaries from both parties, have argued for abolishing the limit altogether. Voices in this camp claim the limit imposes unnecessary costs on taxpayers, puts the solvency of the U.S. government at risk, and does little to rein in federal spending. Others argue that forcing Congress to vote to raise the debt limit is a useful lever to impose fiscal discipline in Washington.

What if Congress doesn’t act?

Unable to meet all its obligations, the Treasury would have to choose which bills to pay. Failure to pay Social Security or other benefits on time would have obvious political ramifications. During the 2021 round of extraordinary measures, Treasury Secretary Yellen warned that running out of cash would put “[e]very Social Security beneficiary, every family receiving a Child Tax Credit, every military family waiting for a paycheck or small business owners receiving a federal loan … at risk.” In addition, a failure to make interest or principal payments on time—a default—is likely to damage the way the markets view U.S. government debt, perhaps increasing the interest rates that investors demand when they buy Treasury bonds. But Congress has never failed to act in time, so no one knows with certainty what the consequences would be.

Transcripts from an August 2011 Federal Open Market Committee meeting reveal that officials at Treasury and the Federal Reserve had planned to prioritize interest payments on the debt over other government bills if Congress didn’t raise the ceiling. Their objective was to discourage investors from fleeing Treasuries and inciting volatility in capital markets. Even with the promise of interest payments, however, Fed officials noted that a debt breach could make rolling over matured debt—a crucial part of cash flow—difficult. Rollover occurs when short-term securities mature, but the proceeds are either reinvested by the original owner or other investors put their money into Treasury securities. If investors react poorly enough to a debt breach, the Treasury could have a hard time finding buyers for those short-term securities, and in turn, would suddenly have to make payments on a portion of its debt. In short, the debt situation could escalate very quickly depending on how investors reacted to the first breach.

For more on what might happen if the debt ceiling isn’t lifted before the Treasury runs out of cash, see “How worried should we be if the debt ceiling isn’t lifted?”.

As long as Congress acts, even at the last minute, is everything OK?

No. There’s evidence from a 2013 debt ceiling impasse—when Congress waited until the last minute to raise the debt ceiling— that investors dumped Treasury securities that had maturity dates around the projected limit date. In turn, rates on those securities rose sharply, and liquidity in the Treasury securities market dropped. In fall 2017, yields on short-term Treasury bills spiked leading up to the projected limit date, as investors signaled they were worried about the possibility of default. Because many financial transactions rely on Treasuries for collateral and for low-risk investment, those effects ripple throughout financial markets. Beyond that, higher yields on Treasuries have a direct cost on taxpayers because they make federal debt more expensive. A Government Accountability Office study estimated that the 2011 debt limit showdown raised Treasury borrowing costs for debt that matured in 2011 by $1.3 billion.

To learn more, see:

March 2019 Hutchins Center slides on debt ceiling (PowerPoint download)

The Bipartisan Policy Center’s interactive on the debt limit through the years

The fiscal fights of the Obama administration

The Bipartisan Policy Center’s 2022 analysis of the debt limit

The Congressional Research Service’s brief report on federal debt and the debt limit in 2022

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What is the federal debt ceiling?

July 7, 2025