In 2012, 149 countries around the world received more than $125 billion of Official Development Assistance (ODA). Keeping track of those disbursements is no small feat. Measuring the effectiveness of the aid requires even greater legwork.

Fortunately, data on ODA—unlike data on aid from many philanthropic organizations around the world—is systematically collected and monitored by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). This allows researchers to not only measure aid effectiveness from DAC countries and agencies, but to also monitor improvement over time and develop best practices for improving impact.

In total, 31 DAC member countries and agencies reported on their aid disbursements in 2012. In their latest report, Brookings’s Homi Kharas and Nancy Birdsall of the Center for Global Development look at that data to analyze the quality of ODA from those 31 DAC member countries and agencies based on four main elements: (1) maximizing efficiency, (2) fostering institutions, (3) reducing burden, and (4) transparency and learning.

The new report is the third edition of the Quality Official Development Assistance (QuODA) assessment. For the first time, it also examines non-DAC donors that have reported data about their ODA.

What’s Improved—and What Hasn’t

When it comes to improvements in the quality of foreign aid from 2008 to 2012, Kharas and Birdsall find that the results are mixed. While some progress has been made with ODA, many elements haven’t improved. Here are a few takeaways from the study’s examination of ODA based on the four main elements:

Maximizing Efficiency: Few Improvements Have Been Made

Few donors have shifted their aid allocations to poor countries. Of course, given that developing countries themselves have been growing rapidly, donors would automatically be giving more funds to less poor countries. But that simply reinforces the need for more active management of strategic country allocations.

In the same vein, donors have not shifted resources toward better governed economies, but have actually done the opposite. Long lags between donor allocations and shifts in country governance rankings caused donors to see the governance of the recipient countries deteriorate on average. Exceptions include Portugal, Norway, and EU institutions, which seem to have taken governance most seriously.

Fostering Institutions: A Bright Spot in Aid Quality Improvements

Donors have made progress on giving countries a greater say in their own development. The share of aid going to countries that recipient country respondents identified in polls as their primary concern has doubled, with Sweden, the UK, Ireland, Luxembourg, and EU and UN institutions recording the largest percentage increases.

The “missing aid” between what donors reported and what governments said they received has almost disappeared. UN agencies, Australia, New Zealand and Spain saw extraordinary improvements. But Italy had an issue: recipients reported receipt of less than 85 percent of what Italy reported giving.

Reducing Burden: More Work Is Needed

Some countries, like India, have encouraged very small donors to exit. The burden of sustaining the relationship is simply not worth the amounts of aid involved.

With more donors, however, the significance of each donor-partner relationship (scored to reflect the relative concentration of aid), is diminishing. For example, the U.S., Sweden, and France have seen sharp decreases in the significance of their aid relationships.

Transparency and Learning: Substantial Progress Has Been Made

Many donors are members of the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), with the U.S., Canada, and several large multilateral agencies having joined since 2008.

Donors have also become far more meticulous in the way they record their activities, with very good compliance on major categories.

Ranking Donor Countries and Agencies

This year’s report ranks each of the 31 members of the DAC according to the four elements outlined above. Kharas and Birdsall’s analysis uncovers no clear winner in terms of who is providing the most effective ODA and almost no correlation across the rankings of the four categories.

Here are a few of the many interesting takeaways from the rankings:

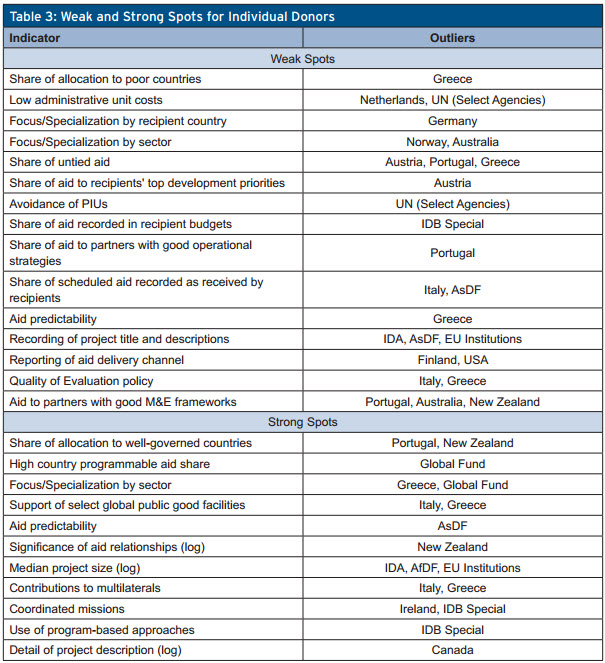

Most donors have strengths and weaknesses. Out of the 31 donors and major agencies assessed, 22 have a top 10 ranking in at least one quality dimension, while twenty-two of the donors and major agencies also have a ranking in the bottom 10 in at least one dimension.

Italy and Greece have small aid programs, but they are strong supporters of global public goods, as well as contributing a high share of their aid to multilateral agencies. By doing this, they significantly reduce the burden on recipients of having to deal with multiple small aid programs.

Canada provides the greatest detail in its description of aid activities, bringing transparency to its program and allowing others to avoid waste by identifying where there may be overlap with Canadian activities.

The UN agencies continue to use parallel project implementation units, far more than other donors.

Both Australia and New Zealand have long provided significant amounts of aid to small neighboring island economies. These economies, however, still appear to have a far worse than normal framework for monitoring and evaluating their development activities.

Ireland ranks in the top four in every category.

Here’s a full table of weak spots and strong spots for individual donor countries and agencies:

Who Else Reports on Official Development Assistance?

Systematic reporting by these 31 DAC member countries and agencies allows researchers to analyze, over time, improvements to the quality of international development assistance. This speaks to the benefits of aid transparency. With more data, we can learn more and improve impact.

The good news is that some non-DAC donors are starting to report on their aid activities to the OECD. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has become the first non-governmental agency to do so. The Gates Foundation disbursed $2.13 billion in 2012, making it the 15th largest donor agency in the world. Kharas and Birdsall write that “the addition of non-state actors like the Gates Foundation…represents a significant step towards the overall goal of improving the transparency and comprehensiveness of aid activities around the world.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Evolution of Foreign Aid Research: Measuring the Strengths and Weaknesses of Donors

July 11, 2014