Across the country, the push to rapidly deploy renewable energy infrastructure—especially in the form of big “utility-scale” projects—is colliding with local concerns and, in some cases, creating fierce battles in court. While the need to reform and accelerate permitting for these projects has garnered most of the attention, that need obscures an underlying problem: The conventional approach to developing energy infrastructure won’t be good enough.

In California, the stakes, the meaning of “good enough,” and the possible choices are starkly on display in the far north of the state, in the Redwood Region, centered on Humboldt County. What’s set to unfold there is a microcosm of what it will take to navigate the net-zero transition fairly and effectively in communities nationwide.

This low-income, mostly rural coastal region is home to nine federally recognized tribal nations and possesses vast amounts of potential offshore wind energy. The public-private effort to harness and transmit that energy is now in full swing, thanks to a federal auction of the leases to produce power offshore and ambitious commitments the governor of California articulated last May in an executive order to coordinate the use of major federal funding to achieve both climate and economic development goals.

Now, the practicalities. This is not one but three taxpayer-subsidized mega-projects, each with budgets in the billions: 1) creating and installing the offshore wind farm itself; 2) major expansion and upgrades to the port in Humboldt Bay to serve that construction and facility operation; and 3) the same required for power transmission, aka, “the grid.”

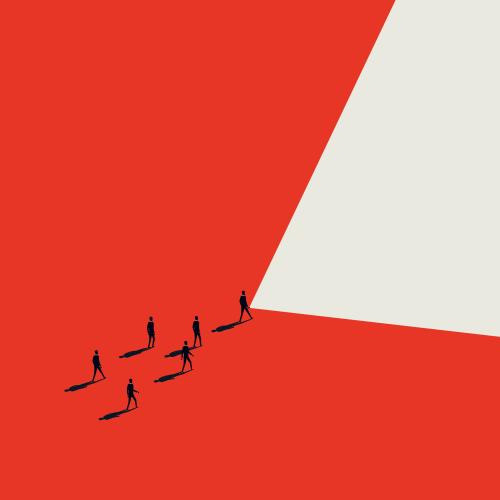

Though that effort will take decades, the right choices about the electric grid are especially critical at this point. These choices will tell us whether we are on a business-as-usual “low-road” path or a sustainable and inclusive “high-road” one that benefits the local energy-producing community that will host this massive new offshore wind complex. Taking the high road is not only the right moral choice—it’s also critical to garnering local support.

The business-as-usual approach is primarily an engineering and financing puzzle, and all of us, as energy users, should understand it: figuring out how to produce and move power from Point A—often in a rural region—to Point B in an urban one, where there’s a concentration of industries and households. In the Redwood Region, that means producing wind power—enough to supply about 6% of the state’s current energy demand, or the equivalent of 1.7 million homes, mainly for customers in the Bay Area.

Under business-as-usual, local needs, harms, and hopes are often secondary, if they are considered at all—even though operating large facilities often generates a range of local burdens, from strains on underinvested local services and infrastructure to disrupting fisheries and threatening Indigenous cultural sites.

The offshore wind farms will generate far more power than local people and industry need. Yet much of the region, especially its tribal communities, still lacks access to affordable, reliable, or clean power. As a matter of basic fairness—and also to redress the extractive policies of the past—the region should benefit from the renewable energy it will produce. The decision about whether to upgrade and connect the local grid to offshore wind power is expected shortly. Based on past projects, the cost to do so would be modest as a share of the larger transmission investment.

Beyond that step, an inclusive energy strategy could encourage more microgrids and other solutions to improve affordability as well as resilience to the growing impacts of a changing climate. It could dramatically accelerate the region’s transition away from its current reliance on a local power plant fueled by natural gas. And placing some transmission lines underground would reduce the risk of wildfires and other hazards.

History matters as the path forward gets defined. Analysis by the Schatz Energy Research Center (based at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt) shows that no large-scale investment in transmission has happened in this low-income rural region since the mid-20th century, when it enabled the rapid expansion of timber extraction, including enormous quantities of old-growth redwood. The logging boom followed the pattern of the Gold Rush a century earlier: extracting wealth for investors outside the region while generating serious social and environmental harms, including contamination, and few lasting local benefits. Following a longer history of land grabs and violence against tribal nations, industrial-scale logging also added to a basic mistrust of outside agendas and promises.

Today, the critical upcoming connection decision sits with the California Independent System Operator (CAISO), a nonprofit public benefit corporation that is one of seven regional transmission authorities in the U.S. In California, two other organizations are also involved in transmission planning: the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulates the investor-owned utilities in CAISO’s area of authority, and the California Energy Commission, which forecasts electricity demand and espouses “a clean energy future for all.” If a decision is made to develop transmission infrastructure, CAISO solicits bids from prospective developers through a competitive process.

It’s not just energy hardware that could use an upgrade, but also our institutions. State procurement of transmission lines, led by CAISO, generally involves limited pathways for public input. These authorities do little tribal or community outreach, and their meetings—suited to industry professionals—are highly technical. Laws written long ago to make the regulators in this picture as technically competent and insulated from partisan politics as possible also place them far from public view—and far from the pressure to ensure accountability, not just to state or nationwide priorities but to the underserved and often economically distressed communities now on the front lines of climate action.

We have a long history with mega-projects in this country, and it is a very mixed one for the communities that host them for the sake of some “greater good.” In California’s Redwood Country, the Klamath River dam system is a powerful reminder of this. Once a major hydropower source, it is now the largest dam removal and river restoration site in history. The tribal communities that stewarded the river for millennia were promised the benefit of power. A century later, Klamath Basin Tribes still suffer weeks of power outages during inclement weather, and some parts of their reservations lack electrification altogether.

It’s time to end mega-project malpractice once and for all. The high-road approach that does just that is now in plain view. It is the more resilient path in multiple senses of the word. Thanks to historic federal funding, it is also affordable—and absolutely essential to the broader climate agenda.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The clean energy revolution is headed through rural and tribal communities. It’s time to choose the right path.

March 27, 2024