The 2016 Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) concluded on April 1—four days shy of the 7th anniversary of President Barack Obama’s Prague speech, in which, among other things, he announced a “new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.” The 2016 NSS was the fourth and final summit held in its current format. Obama expressed the hope that the 2016 summit would leave behind an enduring international nuclear architecture for securing highly enriched uranium (HEU) and plutonium.

What happened?

Leaders and representatives of 52 countries and four regional and international organizations attended the summit. It produced gift baskets (political commitments signed by groups of participants), five action plans for existing international bodies, new national and multilateral commitments, a contact group to oversee implementation of commitments made, and a final communiqué.

Gift baskets

A total of 13 gift baskets were presented during the summit, though many of them built upon previous commitments. Three were particularly notable:

- Twenty-seven states signed the gift basket on insider threat mitigation, committing states to establishing and implementing measures on a national level to mitigate threats from insiders.

- Twenty-nine states signed the gift basket on cybersecurity for industrial control and plant systems at nuclear facilities. These signatories agreed to participate in two international workshops to facilitate sharing of best practices and review the impact of utilizing information technology.

- Twenty-two states signed the gift basket on minimizing and eliminating the use of HEU in civilian applications. The progress made by its signatories on HEU reactor conversion or shut down; HEU stock removal, downblending, or disposition; and the development of low enriched uranium (LEU) alternatives is set to be reviewed at an international conference in 2018.

Action plans

The summit produced five action plans:

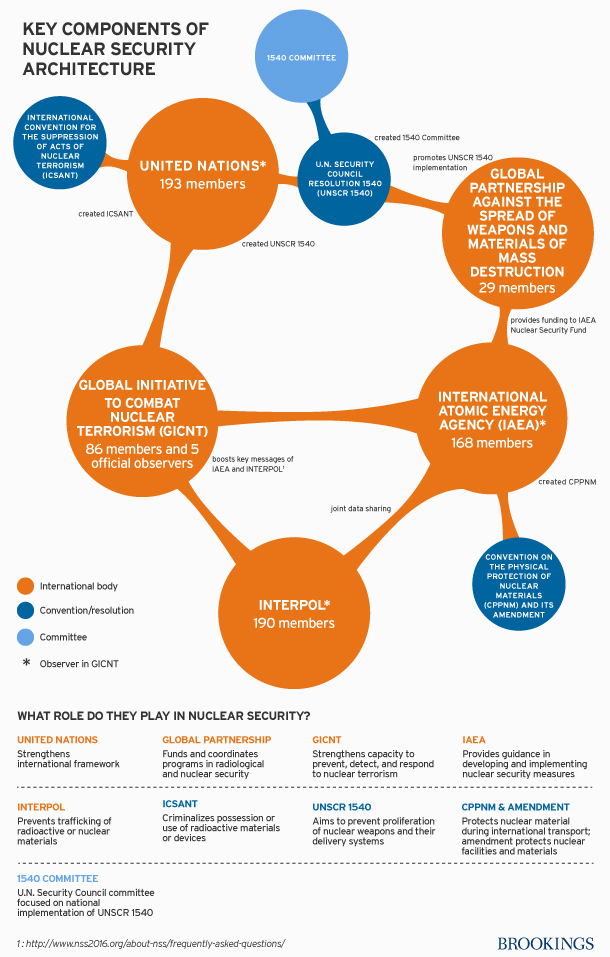

- The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) action plan called for the organization to hold ministerial meetings on nuclear security, take a stronger lead on coordination between states and international bodies, and minimize the use of HEU.

- The United Nations action plan focused heavily on deepening implementation of U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1540, which calls on states to take steps to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, and the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism.

- The INTERPOL action plan discussed increasing INTERPOL’s role in improving states’ information-sharing capabilities, enhancing Operation Fail Safe and the “Green Notice” tool (which track and alert states about individuals involved in nuclear and radioactive material trafficking), and expanding development of best practices guidelines, trainings, and courses.

- The Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT) action plan emphasized augmenting the technical capacity of GICNT partner states and conducting scenario-based discussions, and tabletop and field exercises.

- The Global Partnership against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction action plan directed the partnership to provide broader assistance to states and coordinate programs and activities, and to strengthen its role in UNSCR 1540 implementation by working with the 1540 Group of Experts to match resources with funding requests.

Other highlights

It was announced that the amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials is set to enter into force 11 years after its initial adoption. IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano said he will bring states “together to work out ways of improving the mechanisms for sharing information,” such as information on sabotage and credible threats of sabotage. Amano also discussed his “plan to host annual meetings of national points of contact for the convention, as well as periodic review conferences,” in an effort to promote comprehensive implementation of the amendment and the convention.

Additionally, the Nuclear Security Contact Group was created. This group will consist of senior expert officials from summit states (known as Sherpas) and from states outside the NSS process. The group will meet on a regular basis to “synchronize efforts to implement commitments” that were made during the NSS process.

China and Japan took significant national steps. China agreed to sign onto the 2014 gift basket “Strengthening nuclear security implementation” (which India also joined), established its first Center of Excellence on Nuclear Security, and converted an HEU research reactor so it could use LEU. Japan completed the removal of HEU and separated plutonium fuels from its Fact Critical Assembly (FCA) and committed to removing all HEU fuel from the Kyoto University Critical Assembly. The FCA removal was the largest single nuclear material removal in the NSS process.

The United States undertook several unique unilateral actions. It declassified its inventory of HEU as a transparency measure and released a statement describing the measures it has in place to secure nuclear materials used for military purposes. A statement on the directions it gave the Navy and Department of Energy to consider developing LEU fuel for use in naval reactors was also released.

Nuclear security gaps

Despite NSS successes, experts and policymakers have pointed out critical gaps in the international nuclear security architecture. Miles A. Pomper of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies identified several areas of concern: the lack of security for non-civilian use fissile materials (83 percent of these materials are classified as military and are not subject to any standards) and high-risk radiological materials, and the growing stockpiles of separated plutonium. In addition, the Nuclear Threat Initiative’s March 2016 report entitled “Global Dialogue on Nuclear Security Priorities: Building an Effective Global Nuclear Security System” discussed the uneven and inadequate security of materials that has resulted from a lack of universally-implemented international standards.

What comes next?

The NSS process has fallen short of Obama’s announced goal of securing all vulnerable nuclear materials. Still, it has drawn high-level political attention to the problem and made definitive progress toward that goal. Discussions on the topic will continue during the IAEA’s Conference on Nuclear Security in December 2016.

It is clear, however, that much remains to be done to secure dangerous nuclear materials that remain vulnerable to theft and sabotage. How the international architecture put in place by the NSS process will function without the political push of regular summits remains to be seen. The next president and his or her administration will want to monitor this and decide whether additional steps are needed to strengthen that architecture.

Graphic courtesy of Rachel Slattery.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Takeaways from Obama’s last Nuclear Security Summit

April 4, 2016