It is one thing to lament the lack of opportunity in America, quite another to act to improve it. Solutions are complex and slow to take effect, and national politics are deeply divided. But at the local level, there has been an upsurge of new experiments, solutions, and metrics. This week, for instance, saw the launch of Santa Monica’s index of community well-being.

Santa Monica: California dreaming?

The Santa Monica team turned to the new science of well-being to assess the state of the city’s progress and prosperity, reaching out to academic experts (including me) for advice. Why well-being rather than standard income measures? In order to:

- Understand the factors that matter most in people’s lives;

- Manage trade-offs between different objectives, such as the environment and the economy;

- Identify virtuous circles, such as between health, wealth, and well-being.

Five dimensions of well-being were selected: community, place, learning, health, and economic opportunity. The city has an image as an idyllic ocean-side community; and on average, the results support this. Most survey respondents report good health, are engaged in their communities, and feel happy most of the time. Residents have above average educational attainment and incomes and vote and volunteer at higher rates than other Californians and Americans.

Not all skateboards and sunshine

But Santa Monica also suffers from substantial inequalities across neighborhoods, races, and age groups — a microcosm of some of our national distributional challenges. The city also has some of the highest housing costs in the country: 53% of survey respondents report that it is unlikely that their children will be able to afford staying in Santa Monica, and 37% of residents aged 18-34 are concerned about missing rent or mortgage payments.

Generation gaps in well-being

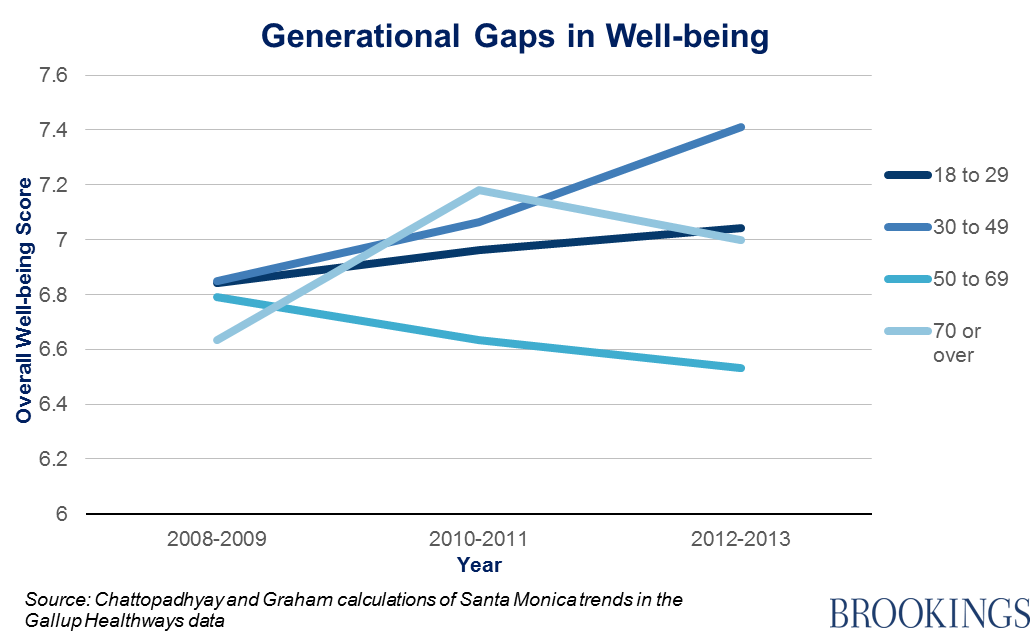

The financial crisis had a deep impact on the employment prospects of American youth, even those with college educations, and Santa Monica is no exception. The youngest age groups report the lowest well-being in many dimensions. More than a third (35%) of 18-34 year olds report feeling stressed all or most of the time (compared to less than 10% of the oldest residents). Younger residents also have higher levels of economic worry — more than a third (37%), compared to less than 30% for the general population. In contrast, the middle aged (30 to 49) and the oldest (70+) age groups generally score highest on overall well-being:

Latino well-being

Latinos comprise 14% of Santa Monica’s population and consistently scored lowest across multiple dimensions of well-being. For example, 13% reported being very worried about paying their housing costs, compared to 6% of non-Latinos. Latino residents tend to be concentrated in parts of the city have higher levels of crime, noise, and poor housing quality. In short, they lead very different lives from the residents of wealthy Santa Monica zip codes.

Local action, local metrics

None of these findings are particularly surprising: the important departure is that Santa Monica is taking on the problems and recognizing that good policies cannot be made without adequate assessments. Metrics matter for policy design and for focusing public energy and attention on the problems at hand. Santa Monica joins a growing list of communities and cities around the world showing that when it comes to opportunity and well-being, it makes sense to think local.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tackling opportunity and well-being, Santa Monica-style

April 30, 2015