Scholar Evans J.R. Revere offers another perspective on China and North Korea’s nuclear dynamics in a complementary piece.

While both Washington and Beijing are officially committed to the denuclearization of North Korea, neither country presently appears to be prioritizing denuclearization as its policy objective. Beijing and Washington are working in their own ways to restore connectivity with North Korea’s leadership. What issues in their relationship with North Korea will they prioritize? And will their respective efforts be complementary or in competition with each other? Will the sum of various efforts at outreach to Kim Jong Un by U.S. and Chinese officials increase or decrease the risk of conflict in Northeast Asia?

To assess the role China can play in addressing the North Korea nuclear challenge, the Global China project convened five scholars with unique backgrounds and expertise to weigh in on current dynamics on the Korean Peninsula: Jeffrey Feltman, Jennifer Hong Whetsell, Patricia Kim, Randall G. Schriver, and Andrew Yeo. Their written exchange focuses on four major questions:

- What is the most concerning aspect of North Korea’s nuclear program, and will China act as a stabilizer or enabler?

- Where do U.S. and Chinese interests align or diverge on the Korean Peninsula?

- How will North Korea-Russian relations impact U.S. and Chinese actions toward North Korea?

- How does the United States want China to act toward North Korea? Can the United States shape Beijing’s policies toward Pyongyang?

Their analysis offers a multidimensional look at the complex factors involved in managing the risks posed by North Korea’s nuclear program. Their responses follow below:

North Korea’s nuclear challenge and the China factor

What is the most concerning aspect of North Korea’s nuclear program today—capability development, potential proliferation, crisis instability, or something else? How does China fit into this equation? Is Beijing more likely to act as a stabilizer that helps manage these risks, or as an enabler that complicates U.S. and allied efforts?Jennifer Hong Whetsell and Randall Schriver

The most concerning aspect of North Korea’s nuclear program today is its expanding cooperation with Russia, which could significantly accelerate North Korea’s nuclear capabilities and broader technological development, including space assets. This partnership not only enhances Pyongyang’s strategic reach but also emboldens Kim Jong Un, reinforcing his perception of elevated global standing. The result is heightened risk of miscalculation and regional instability, especially as North Korea grows more confident and less constrained.

China’s role in this dynamic is nuanced. Beijing is neither a reliable stabilizer nor a direct enabler. It seeks to avoid regional chaos that could spill over its borders, yet it remains focused on limiting U.S. influence on the Korean Peninsula and across the Indo-Pacific. While China does not want a more provocative, or let alone, an emboldened North Korea, Beijing also resists actions that would inadvertently strengthen U.S. alliances or justify an increased U.S. military presence. This undermines efforts by the United States and its allies to manage growing threats by North Korea.

Patricia M. Kim

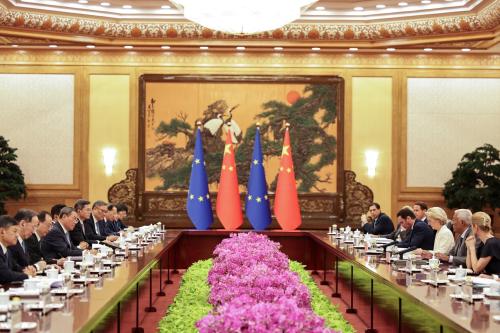

The most concerning aspect of North Korea’s nuclear program today is its unchecked expansion amid global indifference. Pyongyang appears to face no real constraints, as neither the United States nor China is taking meaningful steps to curb its nuclear buildup. Years of failed diplomacy have bred cynicism, and the absence of coordinated pressure has effectively given North Korea free rein. While Beijing continues to state that its policy of supporting the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula remains unchanged, its actions tell a different story. Xi Jinping’s recent meeting with Kim underscored this contradiction: the Chinese readout emphasized “friendship” and “practical cooperation” but made no mention of “denuclearization,” in contrast to previous readouts from the past five summits between the two leaders. China’s main concern now is balancing North Korea’s growing alignment with Russia and keeping Pyongyang within its orbit. In effect, Beijing is acting as an enabler—prioritizing influence and regional leverage over curbing a nuclear threat that undermines long-term stability.

Andrew Yeo

Among several concerns regarding North Korea’s nuclear program, one issue in particular rises to the forefront: the rapid advancement of its delivery systems. North Korea tested an array of short, medium, and long-range missiles in 2022. This included a successful test of its Hwaseong-17 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which has a range capable of hitting most parts of the mainland United States. Currently, North Korea is developing its next generation of ICBMs, including the Hwaseong-20. North Korea also unveiled a new ballistic missile submarine in 2023 and regularly tests cruise missiles to demonstrate its counter-nuclear-attack capabilities. Although China has expressed concern regarding North Korea’s nuclear program, it has been less vocal about addressing the regime’s rapidly advancing missile capabilities. This is surprising given Beijing’s alarm over U.S. theater missile defense systems aimed at reducing North Korea’s missile threat. More conversations between China and the United States (and U.S. allies) regarding North Korea’s expanded missile program and weapons delivery systems could help mitigate the risk of escalation and conflict in Northeast Asia.

Alignment and divergence of interests

How do U.S. and Chinese interests align and diverge when it comes to addressing the North Korea challenge? Are there genuine prospects for coordination on specific areas of the North Korea challenge? Where do U.S. and Chinese strategic priorities remain fundamentally at odds?Jeffrey Feltman

Neither Washington nor Beijing desires war in northeast Asia. Presumably, the United States and China have a shared interest in stability on the Korean Peninsula that, at least in theory, should encourage joint efforts on risk reduction. To manage risks and reduce the danger that miscalculations or mishaps might provoke an unintentional war on the Korean Peninsula, Pyongyang must be involved. Talks focused narrowly on risk reduction could also conveniently sidestep the sensitive issue of defining North Korea’s nuclear status.

But North Korea—which again cut off the military hotline in April 2023—has to agree. With his new bromance with Russian President Vladimir Putin and his September visit to China, Kim Jong Un has yet to show any interest in renewing dialogue with the United States. He may view unpredictability and erratic behavior as strategic assets, keeping the United States and South Korea off balance.

Traditionally, Washington and Beijing have also had overlapping interests in nuclear non-proliferation. Beijing did not want North Korea’s nuclear program to provoke South Korea and Japan into “going nuclear.” But in March 2024, China abstained while Russia vetoed the renewal of the so-called “1718 Committee,” the U.N. panel of experts monitoring the implementation of sanctions aimed at North Korea’s nuclear program. China, which has some leverage over Moscow because of the war in Ukraine, prioritized its relations with Russia over its non-proliferation concerns. This prioritization complicates the potential for U.S.-Chinese cooperation in this area.

Jennifer Hong Whetsell and Randall Schriver

U.S. and Chinese commonality aligns around shared aversions rather than around a shared interest or a shared concept of optimal end states. Both countries desire to avoid conflict or crisis on the Korean Peninsula, but they diverge sharply in most other ways. For Washington, denuclearization and regional stability reinforce the U.S. alliance with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and broader Indo-Pacific security. For Beijing, Chinese officials would prefer to see U.S. forces removed from the Korean Peninsula. Barring that, however, a second best for the Chinese Communist Party is for North Korea’s modulated and contained provocations to keep U.S. forces on the peninsula and focused on the threat from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). If forward-deployed U.S. forces remain in the ROK, Beijing certainly hopes those forces are not easily made available to participate in other activities that could confront China. In sum, both the United States and China prefer a degree of stability in North Korea; historically, they have pursued this through fundamentally different means.

There are limited prospects for coordination. The United States and China may both see value in curbing DPRK-Russia cooperation, for example, but operationalizing cooperation around this objective would surely be complicated. Neither the United States nor China wishes to see horizontal proliferation, and this may lead to complementary diplomatic efforts. However, U.S.-China cooperation on sanctions enforcement has stalled, and on counterproliferation, cooperation has veered toward antagonism.

Patricia M. Kim

In theory, the United States and China share an interest in maintaining peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula, which fundamentally requires freezing and ultimately dismantling North Korea’s nuclear buildup. An emboldened, heavily armed Pyongyang increases the risk of regional instability. It pushes Japan and South Korea to contemplate nuclear options—developments that not only run counter to China’s strategic interests but also risk undermining the global non-proliferation regime. These shared concerns should, in principle, create opportunities for coordination. In practice, Beijing continues to frame the North Korean nuclear challenge as a problem caused by U.S. policy, insisting that Washington take the lead. As a result, coordination has stalled, and both powers appear content to let the problem persist rather than take on the challenge. This inertia allows North Korea’s capabilities to grow unchecked, raising the risks of crisis instability and nuclear proliferation.

Andrew Yeo

I do believe the United States and China both remain committed to the denuclearization of North Korea. However, the two countries have different priorities for the region. Regime stability in North Korea is still a top priority for Beijing. Hence, Beijing remains reluctant to press Pyongyang too hard over denuclearization, even though Kim appears more confident, and his rule appears more stable than ever. China is disinclined to use pressure tactics, such as tightening sanctions or exercising economic leverage over North Korea as its largest trading partner. Meanwhile, Washington sees North Korea as largely a security problem and therefore remains much more committed to reducing the threat of North Korean weapons. U.S. policymakers are less concerned about regime stability. In the early 2000s, regime collapse was even seen as a desirable policy goal.

With U.S. President Donald Trump now seeking (re)engagement with Kim, China and the United States might be able to find some middle ground. Demanding denuclearization upfront is a non-starter for Kim, so the Trump administration may be less wedded to the idea of asking the North Koreans to “go big” on denuclearization and instead focus initially on risk reduction measures. The Trump administration would also rather invest in North Korea than see its collapse. These are goals Beijing could work with to encourage North Korea to restart diplomacy with the United States.

The Russia factor

How does Russia’s support for North Korea affect U.S.-China coordination on North Korea? How do relations between Moscow and Pyongyang impact Beijing’s calculus on the Korean Peninsula?Jeffrey Feltman

Moscow’s support of Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, Washington’s championing of Israel, and China’s protection of North Korea have something in common: the weaker client state has the ability, at times, to vex the stronger patron. Russian diplomats who publicly defended Assad’s butchery would privately note concern about Syria’s intentional starvation of opposition strongholds. U.S. policymakers expressed exasperation over Israeli settlement policies and escalating civilian casualties in Gaza. And Beijing has demonstrated alarm at North Korean moves that could risk an American military response. (At the peak of U.S.-North Korean tensions in 2017, Chinese officials, alarmed by North Korea’s sixth nuclear test and ICBM launch, provided me with extensive briefings—more comprehensive than those from any other government—on North Korea before I led a U.N. delegation to Pyongyang that December.)

Yet despite these clients’ reliance on their respective patrons, those same patrons often prove unwilling or unable to influence the clients on key issues. Domestic politics may come into play (as with Israel and the United States) or capitals may not want to push an issue for fear of being exposed as impotent (as may have been the case with Moscow and Assad’s starvation policies). In practice, the leverage over clients is less powerful—or at least less exercised—than common sense would assume.

What leverage Beijing was willing to exercise over Pyongyang is seriously undermined by the rapprochement between the Russian Federation and the DPRK. Kim’s enhanced relationship with Russia doesn’t replace his dependence on China, but it does give him options. It’s similar to how Assad played Moscow and Tehran off each other.

Patricia M. Kim

Russia’s expanding partnership with North Korea since the signing of their mutual defense pact, forged in the aftermath of the Ukraine war, has significantly altered the regional balance of power. Moscow’s support—including growing military and technological cooperation—has bolstered Pyongyang’s position, reduced its isolation, and weakened both U.S. and Chinese leverage. For Beijing, this trend is unsettling. China is uneasy about North Korea’s deepening reliance on Russia, which diminishes Beijing’s traditional influence over Pyongyang and introduces unpredictable dynamics along its northeastern border. Yet, China is unwilling to risk its strategic relationship with Moscow by pressing it to scale back cooperation with North Korea. Chinese leaders view Russia as a vital partner in countering U.S. pressure. This leaves Beijing in a delicate balancing act: it wants to reassert its influence over Pyongyang without straining ties with Moscow. Consequently, China has little incentive to coordinate with Washington on managing North Korea—or on addressing the growing Russia-North Korea partnership.

Andrew Yeo

Prior to Xi’s encounter with Kim and Putin in Beijing last month, I argued that Russian support for North Korea offered the United States and China an opportunity to work together to ensure that North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities remain in check. Underlying this assumption was the belief that Xi had become sidelined as Kim and Putin’s relationship blossomed, thereby reducing China’s influence over its ally.

However, Xi reinserted himself back into the fray by staging a show of autocratic solidarity between China, Russia, and North Korea at last month’s Victory Day military parade in Beijing. Beijing should still be wary of Russia-DPRK relations to the extent that Moscow and Pyongyang are driven by their own self-interested motives rather than any ideological affinity. But the United States will find it more challenging to work with China if its goal is to peel North Korea away from Russia. Even if China decides to play a constructive role by supporting U.S.-North Korea diplomacy, Beijing may demur when it comes to the Russia-North Korea relationship and offer its usual line that the two countries are free to choose who they work with as partners.

China’s role and U.S. leverage

What role should Washington want Beijing to play in addressing the North Korea challenge? To what extent does the United States have the ability to shape China’s policies toward Pyongyang, and what incentives or disincentives might expand U.S. influence over Beijing’s approach?Jennifer Hong Whetsell and Randall Schriver

Rather than framing the issue as one where the United States might shape China’s policies through carrots and sticks to land Beijing in a more constructive posture, we should understand China’s fundamental interests and priorities and its likely approaches based on over three decades of experience. In sum, shaping China’s policies even on the margins is, unfortunately, highly unlikely.

The United States is best positioned vis-à-vis China (and the DPRK for that matter) when its regional alliances are strong, its messaging is synced, and its alliance activities are well-coordinated and fit for purpose. This is particularly the case when the United States achieves harmonized policies and actions across its trilateral relationship with the ROK and Japan. In such a geopolitical environment, Beijing’s calculations surely become more complicated, and it is forced to weigh broader equities beyond just its relationship with Pyongyang. The net result may be that the prospects for China conducting useful bilateral engagements with the DPRK, and even the possibility of Beijing joining collective diplomatic action aimed at the DPRK, are increased.

Patricia M. Kim

Washington should want Beijing to play a proactive role in constraining North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, using its considerable economic and political leverage as Pyongyang’s main trade partner and economic lifeline. China’s cooperation is essential for signaling that North Korea’s pursuit of recognition as a nuclear power will never be accepted. Ideally, Washington, Beijing, and other major powers would work together to reinforce this message. However, Beijing tends to demonstrate initiative on North Korea issues only when it (a) fears instability on the Korean Peninsula, (b) worries about being excluded from diplomatic processes that shape regional outcomes, and/or (c) sees a direct link between its actions on North Korea and immediate Chinese interests. To that end, Washington might consider elevating coordination on North Korea to the bilateral agenda, just as issues like trade and fentanyl have been prioritized. However, given how much trade issues subsume the bilateral relationship today, such linkage appears unlikely in the near term. Absent U.S. pressure and deliberate prioritization of the North Korea issue, China’s approach will remain passive, reactive, and self-interested.

Andrew Yeo

Chinese officials have reiterated Beijing’s ultimate desire for denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula, which is what U.S. officials want to hear. However, since 2019, China has done little to press the North Koreans to reengage the international community on denuclearization efforts or dial back their missile program. Instead, Beijing has “excused” Pyongyang’s behavior by casting blame on the United States and its allies for escalating tensions. China, along with Russia, has also offered Kim political cover at the United Nations by vetoing any resolutions or additional sanctions condemning North Korea’s actions.

The United States may not have much leverage to dictate how Beijing engages with Pyongyang. But with the prospect of a Trump-Xi meeting taking place on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in October, followed by a potential bilateral meeting at a later date, Xi may want to make a deal with Trump (and vice versa) to place U.S.-China relations on a more stable footing. The desire to improve relations with Washington may make Beijing more amenable to supporting U.S. diplomatic engagement with North Korea in hopes of reducing tensions on the Korean Peninsula and getting back on a path toward a process of denuclearization.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Stabilizer or spoiler? The China factor in the North Korea nuclear dilemma

October 20, 2025