This is the first publication in a four-part series that seeks to provide local leaders across the public, private, and civic sectors with tools to advance inclusive downtown recovery in small and midsized regions.

Over the last five years, many have fretted about the risk of America’s largest downtowns falling into a “urban doom loop,”predicting that pandemic-era declines in office work, retail activity, and tax revenue would inevitably prompt a fiscal death spiral for municipalities. These concerns are only now beginning to subside for some of the nation’s largest “superstar cities” due to promising rebounds in downtown residential activity, weekend foot traffic, and tourism.

Yet the national media has given less attention to the recovery trajectory of small and midsized city (SMC) downtowns,1 even though 1 in 4 Americans live in these cities. Many of these downtowns have a long history of confronting challenges that mirror—but precede—the pandemic-era “doom loop,” including population decline, high concentrations of vacant buildings, and precarious fiscal health.

This report is the first in a four-part series seeking to fill this gap by surfacing insights from downtown recovery efforts in four small and midsized cities: Akron, Ohio; Birmingham, Ala., Cincinnati; and Richmond, Va. While SMC downtowns face barriers specific to their size and context related to inclusive economic growth and sustainability, they are also sites for policy innovation and civic collaboration that local leaders in places of all sizes can learn from to unlock a new era of downtown vitality that advances regional prosperity.

Methodology: A ‘Learning Exchange’ to advance downtown recovery

This research builds upon findings from two in-depth Brookings projects with eight of the nation’s downtowns. The first project began in the fall of 2022 and engaged downtown leaders in Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Seattle to understand the immediate impacts of the pandemic and explore the innovative ways cities were trying to build back “better” and more inclusively. The second project began in October of 2024, when we expanded our downtown research in partnership with Brookings Metro’s Regional Inclusive Growth Network (RIGN), a learning and action network designed to catalyze regional, cross-sector action to advance more racially inclusive growth in eight small and midsized regions (Akron; Birmingham; Cincinnati; Des Moines, Iowa; Kansas City, Mo.; New Orleans; St. Louis; and Richmond). Based on local interest, four SMCs—Akron, Birmingham, Cincinnati, and Richmond—opted into a peer learning exchange focused on unlocking a new era of growth for their downtowns.

To inform this learning exchange, between November 2024 and January 2025, we conducted 98 qualitative interviews with key downtown and regional stakeholders from these four cities, including public sector officials, small business owners, residents, employers, business leaders, and others. We then analyzed key indicators for downtown recovery, including foot traffic, real estate ownership, crime, homelessness, vacancy rates, and others. Based on these findings, we convened SMC leaders in monthly “peer learning” sessions between February and May 2025, organized around themes that emerged from both interviews and quantitative data. The insights provided throughout this paper—the first in a four-part series—draw from this exchange, as well as comparisons from larger cities explored in prior research.

Why small and midsized downtowns matter to regional and national prosperity

Nationwide, downtowns provide a clear example of how “hyperlocal” places drive regional economic prosperity. Brookings’ 2022 analysis of the top 110 U.S. metro areas by population, for instance, found that “activity centers”(hyperlocal areas that cluster economic, physical, social, and civic assets in close proximity, such as commercial corridors, transportation nodes, and employment hubs) form the building blocks of successful regional economies. Despite comprising only 11% of developed land in regions, activity centers concentrate 40% of private sector jobs, nearly half of commercial real estate asset value, and most major anchor institutions (e.g., museums, hospitals, and colleges).

Our research found that there is a significant positive agglomeration effect on productivity when more of a region’s jobs are concentrated in activity centers. In other words, across regions, as job concentration in activity centers such as downtowns and other hyperlocal districts increases, so does overall regional productivity.2 Activity center agglomeration also means less time spent traveling and greater access to culture, entertainment, and social cohesion.

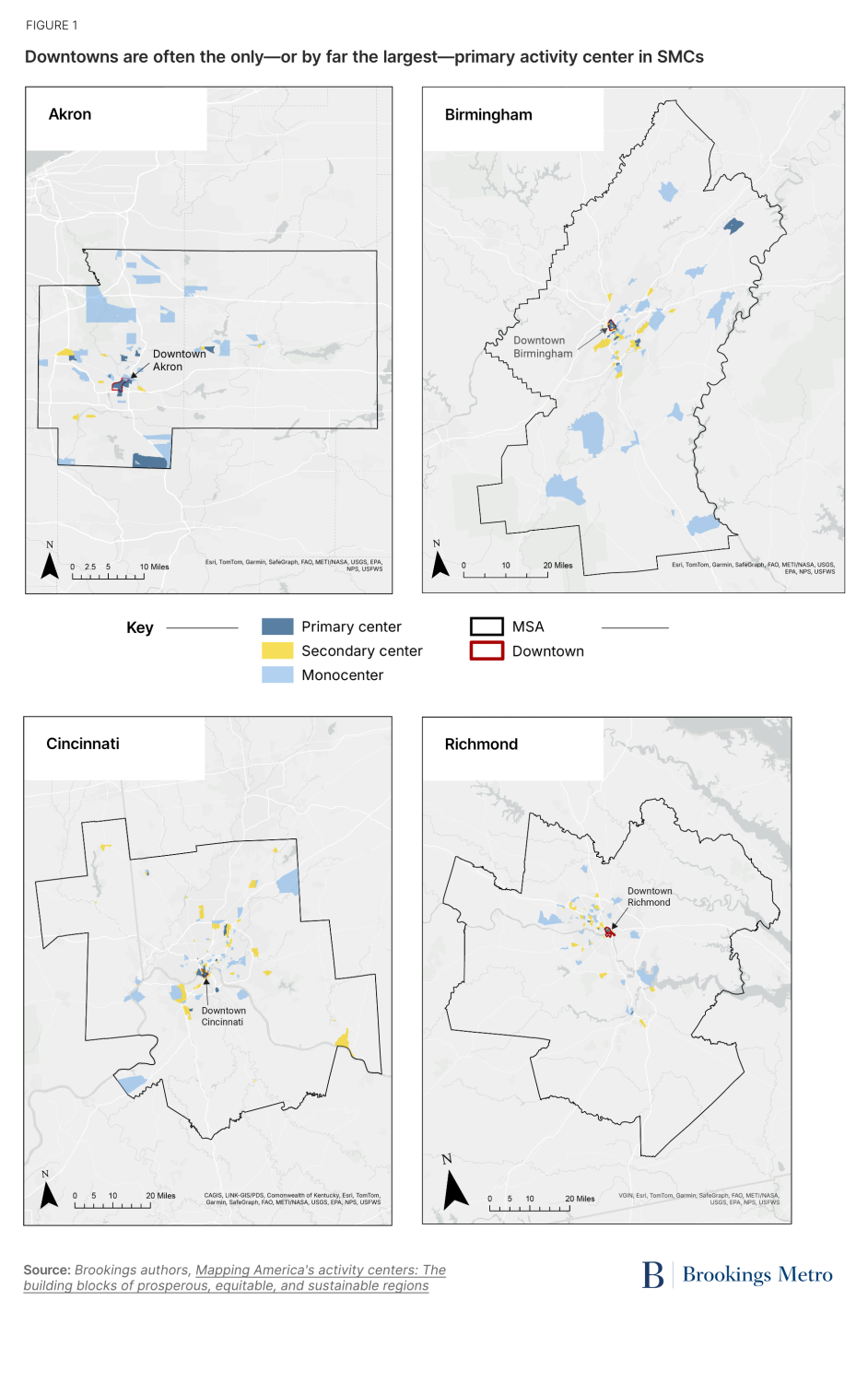

Regional economies organize activity in several geographic configurations. Downtowns are “primary” activity centers, where multiple types of assets cluster together for the longest portions of each day. In and around the largest U.S. cities, such as Seattle and New York, there are many primary centers throughout the region. In regions centered around small and midsized cities, however, downtown is the biggest of just a few primary centers (Figure 1), meaning that downtown is often one of the only major places where employers, workers, and residents can go to access the full benefits of agglomeration. This raises the stakes for SMCs’ downtown vitality in achieving broader regional economic health.

In our previous research, we analyzed the 45 largest American downtowns,3 which consist of 32 major cities and 13 SMCs.4 For major cities, we found that the average share of regional jobs located downtown was 11.4%, while the average residential market share downtown was 1.8%. Table 1 presents updated numbers with more recent data for the 13 SMCs in the original sample, plus Akron. Interestingly, the SMC downtowns have higher average job market share than their major city counterparts. For example, downtown New Orleans has 18.7% of its region’s jobs and downtown Birmingham has 14% of its region’s jobs, compared to the average of 11.4% in larger regions.

While job concentration is a measure of strength and a predictor of regional productivity, this does not mean SMC downtowns are without challenges. In recent macroeconomic history, small and midsized cities have been “on the wrong end of global cities’ gravitational pull,” due to deindustrialization and globalization. Across sectors, leaders in SMC downtowns are working to build on strengths—including walkability, historic core assets, higher social capital, and dense civic networks—to stabilize their communities and regional economies after decades of disruption. As cities across the nation confront the doom loop, there is an opportunity for them to learn from lessons in SMC downtowns. The remainder of this paper is devoted to unpacking some of these findings.

Finding #1: SMC downtowns should lean into their uniqueness rather than paving over it

Within SMC regions, downtowns are relatively unique in their land use mix, density, and urban form. But what makes them special can also make them seem strange, since the economic geography of the rest of the region is more drivable activity centers, such as suburban malls. For SMC downtowns, the context is one where rates of car dependence tend to be high, and thus residents want to access downtown via car (their typical form of transportation). This undermines downtown’s unique value (walkability) with demand for parking, and increases the challenge of cultivating a transit culture.

We are still very much a car-centric community, so naturally many visitors drive down Broad Street as opposed to walking down Broad Street. But I heard from more than one person yesterday say, ‘I am so glad that I'm walking down here, because it's different when you do.’ There is real power in that.

A Richmond stakeholder

We have challenges with our built design, which are a bit hard to overcome…One-third of our surface area downtown is dedicated to parking, and no one realizes that until you tell them. We’re exploring what can be done around zoning and design standards to help solve some of those problems, because what everyone still says is, ‘I want parking’.

An Akron stakeholder

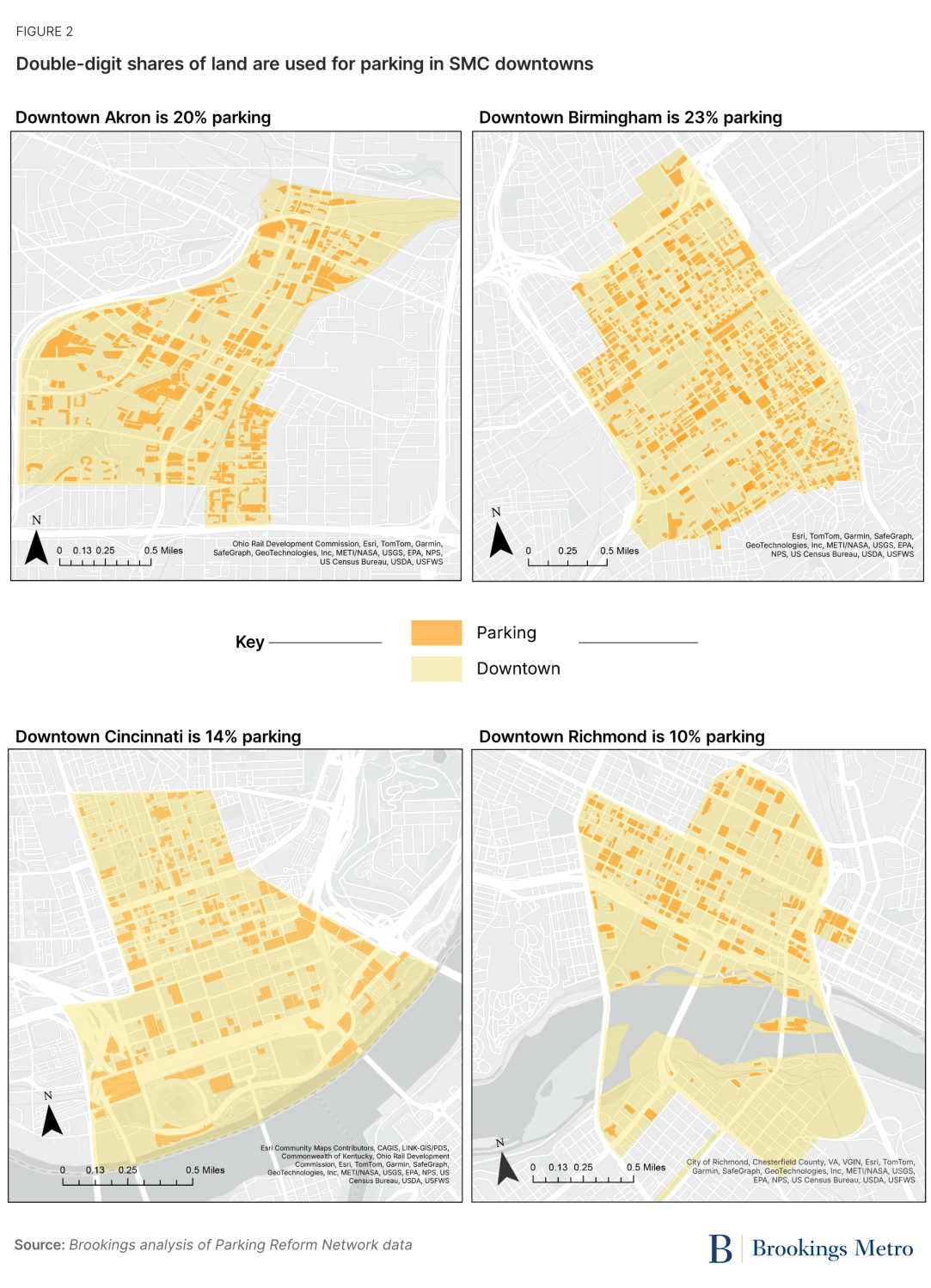

To cater to car commuters, SMC downtowns often have double-digit shares of land devoted to off-street parking (Figure 2). However, even within SMCs, our research with the four learning exchange cities shows that it is possible to use less than 15% of downtown land for parking. Richmond and Cincinnati, for example, have less land devoted to parking and more mature transit systems—a well-established relationship.

Moreover, reduced parking does not necessarily mean more land devoted to offices or housing. Both Richmond and Cincinnati have large pieces of downtown land devoted to public spaces and riverside parks. Akron has invested heavily in Lock 3 park and the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath. Most creatively, Birmingham has challenged the land coverage metric by building 30 acres of high-quality public space under two interstate highways at the edge of downtown. These signature downtown spaces satisfy the enduring surge in demand for outdoor activities that began during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across the four cities, stakeholders spoke of the land use challenges reflected in the data analysis above. They recognized that surface parking overly (and at times unproductively) dominated downtown land use, but these leaders face barriers in cooperating with surface lot parking owners and overcoming public perceptions among residents and visitors that there still is not enough parking. In addition, they described the fiscal challenges associated with other dominant land uses such as high concentrations of public and non-taxable institutions, and discussed the difficulty of getting out-of-state and negligent property owners to maintain and improve their properties, particularly those that have long been vacant.

We not only have a small land mass in the city so we can't tax many things, but we're also the state capital and home of the state university. So what little land the city does have cannot be taxed. That is a huge problem. Not only are our needs greater, but the budget is also smaller.

A Richmond stakeholder

Leaders in the four cities are well aware of these challenges, and are in the process of partnering on new strategic initiatives to activate and develop underutilized land, including by developing new downtown development corporations, exploring financing for community ownership models, spearheading pedestrianization of key corridors through nonprofit developers, and working with partners and developers to address other underutilized assets.

Finding #2: Downtown value in SMCs is closely tied to the diversity, quantity, and quality of assets rather than regional accessibility

In very large metro areas, downtowns bring a high regional accessibility premium due to their central location and transit access. By being the physical center of a vast metro area with greater traffic congestion, large-city downtowns are often some of the most accessible activity centers from elsewhere in the region, especially when hub-and-spoke fixed rail mass transit systems function reliably.

In small and midsized cities, however, if it only takes 30 minutes to drive across the whole region, the relative accessibility premium of a central downtown location is less pronounced, particularly when traffic is less of a problem. We compared the spatial distribution of commercial real estate in four major regions compared to four small and midsized regions. Across all eight regions, suburbs have similar shares of office and multifamily rental inventory. In four SMCs, however, downtown market share is lower and the rest of the city’s market share is higher (Figure 3).

These data points, juxtaposed with higher SMC downtown total job shares, suggest that in SMC regions, downtown’s unique value proposition may be more heavily weighted to the diversity, quantity, and quality of assets beyond office-using jobs. Indeed, in the years since the pandemic, many have mused about the role of placemaking, arts, cultural, and entertainment assets as being the “future” of downtown recovery. Creative placemaking efforts in SMC downtowns have involved a wide and atypical range of participants, from chambers of commerce to transit authorities.

The Civil Rights District is the single best economic development opportunity we have. Not only will it tell our story to our own citizens, but to the outside world…There is also just so much practical short-term possibility from selling hotel rooms and supporting businesses.

A Birmingham stakeholder

Three things would be instrumental to increasing foot traffic and the overall vibe downtown. The easiest would be a temporary art program—art installations that could last anywhere from a month to a year that engage the [bus rapid transit] stations and the facades of buildings…Then, there’s a new building owned by the [Virginia Commonwealth University] real estate foundation that could be a perfect landing point in the Arts District to get information on all the galleries, where to go to eat, and places to congregate…And the third strategy is revitalizing vacant storefronts to become temporary or semi-permanent artist studios or art spaces.

A Richmond stakeholder

Finding #3: Sub-areas within SMC downtowns share big-city problems related to perceptions of safety and reduced foot traffic, while providing small-town solutions

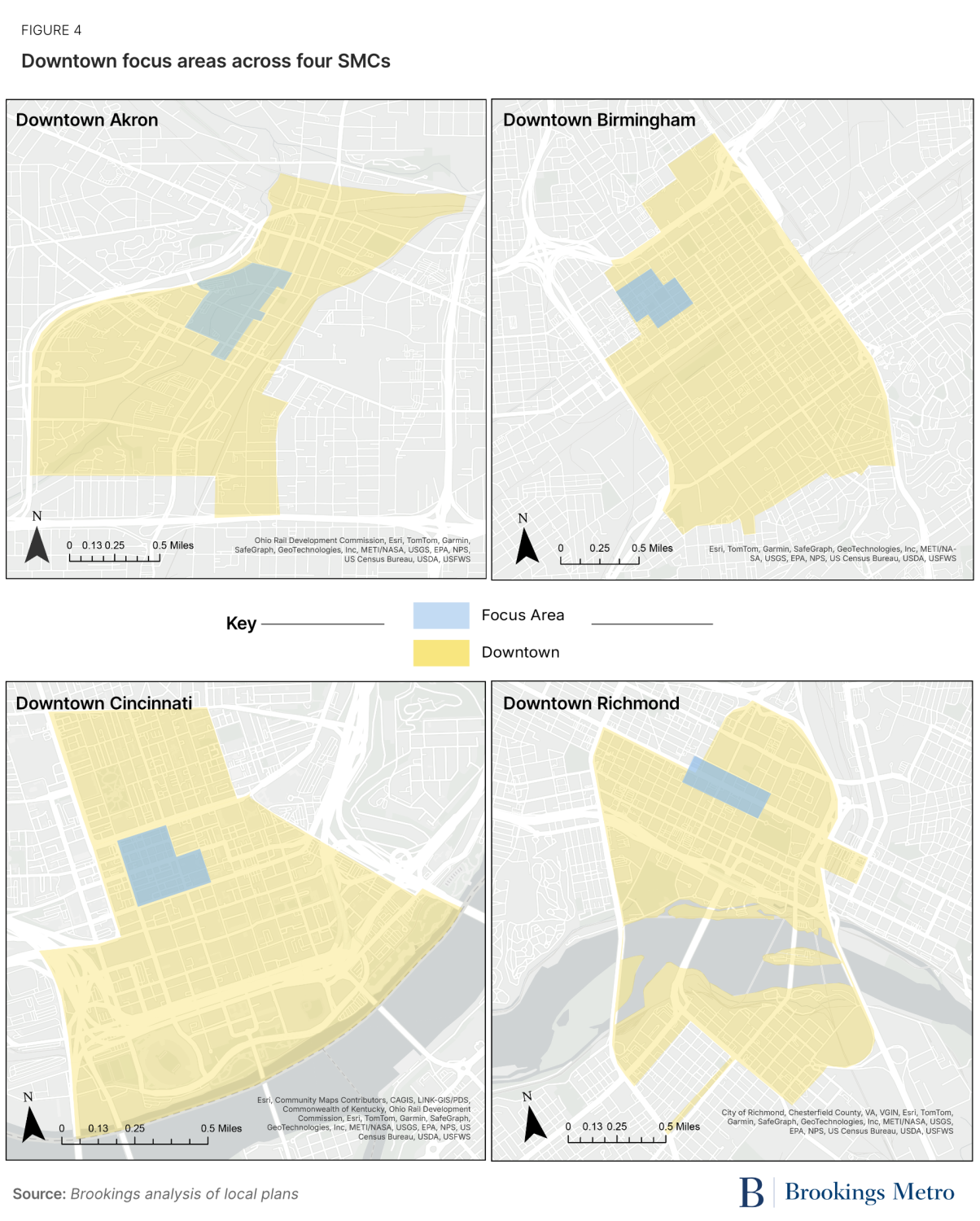

Local leaders in Akron, Birmingham, Cincinnati, and Richmond identified specific “sub-geographies” within their downtown footprint that exemplified more stark challenges than their broader downtown commercial cores—challenges that more closely mirror the barriers in larger cities facing a “doom loop” (Figure 4). These focus areas included the Civil Rights District in Birmingham, the East Broad Street Corridor in Richmond, the Piatt Park area in Cincinnati, and core blocks of the central business district in Akron.

Across the four cities, major employers, property owners, small business owners, and other stakeholders consistently reported rising fear of crime and public disorder to be a key challenge in their downtown focus area. Many of them, however, had reached an awareness that such perceptions are largely tied to decreases in downtown foot traffic and changes in either the quantity, location, or condition of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness.

With the decrease in foot traffic and the actual increase in individuals experiencing homelessness, the two issues together have impacted the perception of safety…Not only are you one of the only 10 people on the street, and now two people are experiencing a mental health crisis.

A Richmond stakeholder.

Indeed, when analyzing foot traffic patterns in focus areas compared to the surrounding downtown, we found that most regions’ focus areas had lagged behind the rest of downtown in foot traffic recovery (Table 2). And when analyzing rates of violent crime in the downtown focus areas, we found significant declines in Birmingham (-80%) and Cincinnati (-45%), with modest declines in Richmond (-1%).5

To address these challenges, downtown stakeholders and their partners are forming new cross-sectoral initiatives to bolster perceptions and realities of safety in their focus areas and beyond. These initiatives include creating new positions for direct homeless outreach within downtown organizations; launching citywide alternative crisis response units that pair social workers with police; convening new downtown safety working groups comprised of business owners, university and police stakeholders, and homelessness providers; and forming new commissions aimed at engaging the business community in addressing crime. Importantly, across all four cities, stakeholders had reached a growing consensus and alignment that “arresting people out of homelessness” was not an effective strategy for downtown safety, and that fostering true public safety requires a holistic set of tools that combines intervention, prevention, and deterrence, with a focus on the most at-risk individuals.

What benefit do we get for putting handcuffs on that homeless person and sending them to the jail? That doesn’t solve anything—they’ll be back there in 10 hours…So now we have all kinds of different resources. We have civilian staff working full time with the police department as social workers…When I first came on in the department, I was asked to be a homeless counselor, substance abuse counselor, marriage counselor, all these things. I only got an eight-hour day of training on these…Now, if we have an issue like that, we won't even dispatch the police. It's goes through our dispatch, but they'll dispatch the civilian specialist, and it’s been a huge success

A Cincinnati stakeholder.

We’ve been looking at how to support the police department with new data to identify high-risk individuals and to provide them with services and pathways to a different life. We’re trying to treat gun violence like you would drug or alcohol addiction. Our first step is to engage without law enforcement and connect them with targeted services and intervention.

A Birmingham stakeholder.

Conclusion

Even with their strong commitment, civic leaders identified challenges with governance and cross-sectoral collaboration, largely related to their limited infrastructure for advancing a cohesive vision for their sub-geographies or limited alignment among district stakeholders. Nevertheless, promising efforts were underway across each downtown to address these collaboration challenges, including land use and zoning reforms, anchor institution partnerships, new funding mechanisms, community ownership models, and efforts to preserve the history and legacy of the district, as well as to invest in entertainment and arts activation.

Collaboration isn't a static achievement. It's a constant, iterative exercise. We constantly have to work on being a collaborative and what it means to be a collaborative.

An Akron stakeholder

Taken together, these findings demonstrate the innovation and nimbleness of small and midsized cities to act boldly and inclusively to advance downtown vitality, even as sub-areas of their downtowns face significant challenges. In particular, the experiences of our four study cities reveal the strong potential for broad, multisectoral coalitions of stakeholders—including business improvement districts, major employers, real estate developers, residents, placemakers, service providers, people with lived experience of homelessness, and multidisciplinary experts—to advance win-win solutions that maximize the potential of regions’ most productive places.

In the coming months, we will publish a series of three reports that dive deeper into each finding from the Learning Exchange with the four SMCs, and offer case studies and actionable policy recommendations to provide tools for such coalitions across the country to help small and midsized cities maximize their potential by connecting downtown prosperity to more neighborhoods and more people.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors extend their deepest appreciation to the participants of the Downtown Learning Exchange and their local partners working to advance economic inclusion and downtown vitality in Akron, Birmingham, Cincinnati, and Richmond, as well as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for supporting this work. Thanks also to Bethany Krupicka and Mary Elizabeth Campbell for research assistance, and Joe Parilla for reviewing an earlier version of this draft. Any remaining errors or omissions are those of the authors.

-

Footnotes

- Defined as cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000.

- Measured as gross regional product per job (R2 = 0.415)

- These statistics rely on commercial core/downtown boundaries defined using a consistent methodology across regions.

- Downtown size is a function of the size of the entire metropolitan area, not just the primary city. Therefore, we refine the SMC definition (cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000) to restrict SMC downtowns to those within regions of 3 million people or less.

- Comparative data from Akron were unavailable during these years due to changes in reporting methodologies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).