Today’s employment report provided some optimism for job seekers, as the unemployment rate continued to edge down and expansions in employer payrolls continued to gather steam. Although still too high, the unemployment rate fell again to 8.5 percent and has now fallen 0.6 percentage point since August. Payroll employment increased by 200,000 jobs in December and by an average of 137,000 over the last three months—a bit faster than the pace of job growth over the summer. Other indicators also signaled a more positive tone, as the number of discouraged workers and number working part-time due to slack demand both declined, and employers expanded work hours for their employees.

When Congress returns and once again considers whether to extend benefits for the long-term unemployed, The Hamilton Project compares the trends in unemployment duration before and after the Great Recession. It has always been harder to find work the longer you are unemployed, but the situation facing today’s workers is exceptional. No matter how long a worker has been unemployed, the odds that they find a job are far lower than before the recession. Furthermore, the odds of experiencing long-term unemployment are highly related to losing a job in a particularly hard-hit industry, like construction or manufacturing, and are disproportionately concentrated in certain distressed states.

Overall, we find little evidence that unemployment insurance (UI) benefits are increasing the time that people remain unemployed. Rather, UI benefits remain a crucial source of support for American workers, most of whom lost their jobs as a result of the Great Recession and not because of their job performance.

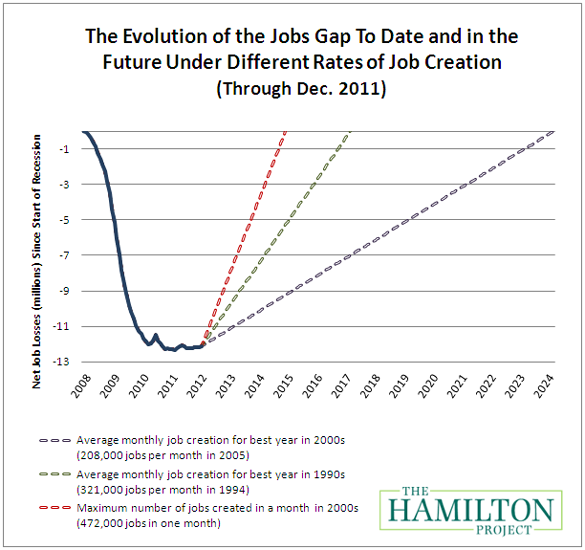

We also continue to explore the “jobs gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

Unemployment Duration and The Probability of Finding a Job

As noted above, it has always been harder to find a job the longer you are unemployed. But the situation facing American workers today goes well beyond historical norms. For all unemployed workers, the probability of finding new employment in today’s economy is considerably lower than it was prior to the Great Recession. Between 2004 and 2007, when the typical person lost his job, he or she could expect to be out of work for about two months before finding re-employment. In May 1983, six months after the end of the 1982 recession, the length of unemployment in the United States peaked at about twelve weeks, or less than three months. Indeed, the Great Recession changed the definition of historical highs and lows. Today, over two years after the official end of the recession, the typical unemployed American has been out of work for nearly twice as long as the unemployed worker in the early 1980s—twenty-two weeks, or about five months.

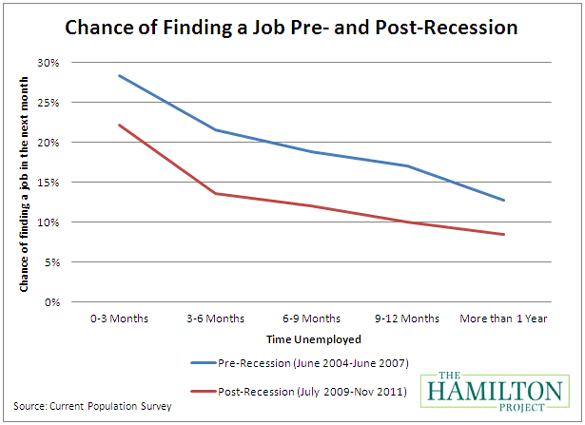

The chart below compares the probability of exiting unemployment conditional on being unemployed in the previous month, both prior to the start of the Great Recession (the blue line) and post-recession (the red line). Unemployed workers have the highest odds of finding a new job in the first three months after becoming unemployed; as more time passes it is more and more difficult for these workers to leave unemployment for a new job. For example, prior to the recession (June 2004 to June 2007), during the first three months of unemployment a worker had roughly a one in four chance of finding a job each month. The chance of finding a job declined the longer they were unemployed, falling to about 22 percent for workers unemployed three to six months, to 13 percent for workers unemployed for more than one year. This pattern is true both before the recession (the blue line) and after the recession (the red line).

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, however, all unemployed workers have had a harder time finding work. In today’s economy, America’s unemployed workers are roughly 7 percentage points less likely to find work each month during the first year of unemployment than they were prior to the recession. This means that for every one hundred individuals unemployed, seven fewer are likely to find a job at any given time in their first year of unemployment.

It is worth noting that these figures measure how long a person is unemployed if they are in the labor force—that is, they are actively seeking work or are expecting to be recalled to a previous employer. On the one hand, they may overstate the chance of finding a job because they do not include the growing number of workers who have given up looking for work altogether. On the other hand, it is possible that unemployment benefits keep more people in the labor force through its requirement that beneficiaries seek work.

Variations in Unemployment Duration Across States

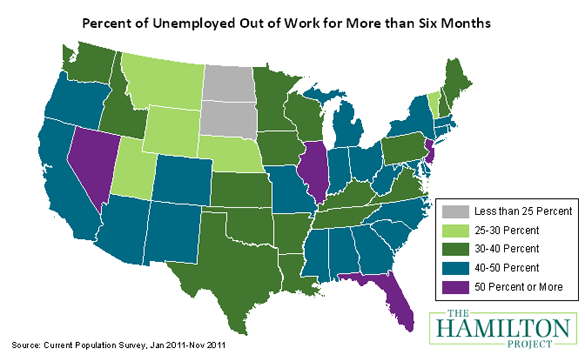

While the nation as a whole was dealt a strong blow from the Great Recession, unemployment has not been evenly distributed among the states. The figure below reports the share of people who lost their jobs and remained unemployed for at least six months (the six month cut-off is relevant because typically this is the maximum length of eligibility for UI benefits).

The figure reveals that the longest durations of unemployment are on the West Coast and the Deep South, and certain states in the mid-west. In four states, at least half of the unemployed were out of work for more than six months over 2011.

[Click here for share of unemployed out of work for more than six months by state]

The highest durations of unemployment were concentrated in occupation and industries hardest hit by the Great Recession, which helps to explain the geographic distribution. People who formerly worked in manufacturing industries have some of the toughest times finding jobs—the typical worker in manufacturing is out of work for approximately thirty weeks. Construction and the public administration industries have also been hard hit, as have certain services, in particular installation, maintenance, and repair occupations, and workers in office and administrative support occupations. As of November 2011, these workers were typically out of work for six months or more and their industries are disproportionately concentrated in the darkest colored states in the figure.

The Importance of Unemployment Insurance for the Long-Term Unemployed

Unemployment insurance benefits are intended to provide a safety net against job loss for reasons beyond one’s control. Because it is hardest to find a job during tough economic times, extending UI benefits helps workers and their families when they need it the most. Beginning in 2008, Congress authorized emergency unemployment compensation (EUC) benefits, extending benefits up to ninety-nine weeks. In December, Congress acted to continue the current program through February 2012 and will debate a longer extension when members return to D.C. After that date, over a million Americans will be at risk of losing UI in the following month if benefits are not extended.

There are some economists who argue that the increase in the duration of unemployment could partially be an unintended consequence of extended UI benefits. These economists argue that workers can be more selective with the types of jobs they accept than they would otherwise be in the absence of unemployment benefits. While this may be true in good economic times, it hardly rings true in tough economic times when employers are not hiring and there is no opportunity for unemployed workers to be selective.

On the whole, there is little evidence that extended UI benefits have contributed to today’s high unemployment rate. For one, as already discussed, the probability of finding a job has declined overall for today’s unemployed workers—whether in the first three months of unemployment of after a full year. Further, research has shown that few workers wait until benefits run out to find a job (Card and Levine 2000; Card, Chetty and Weber 2007) and that the job searching process is ongoing. Data collected on workers who became unemployed during the Great Recession finds that any impacts of benefits on the length of unemployment are, if any, extremely small. Rothstein (2011) finds that extended benefits may have increased the unemployment rate by only about 0.2 percentage points and the long-term share of unemployment by 1.6 percentage points.

The December Jobs Gap

As of December, our nation continues to face a “jobs gap” of 12.1 million jobs, down by 67,000 jobs from November.

The chart below shows how the jobs gap has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, and how long it will take to close under different assumptions for job growth. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the jobs gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until March 2024—over 12 years—to close the jobs gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by February 2017—not for another five years.

Conclusion

The challenges facing today’s unemployed workers are the worst we have experienced since the Great Depression. The probability of finding a job has fallen for workers unemployed for short durations of time, as well as long-durations. Even as the economy begins to recover, it is still harder for unemployed workers to find a job, and it will take them a longer period of time.

Unemployment insurance continues to be an important part of the safety net aiding American workers and their families as they seek new work. Event after they are re-employed, however, many workers will experience reduced earnings in their new jobs. Few resources are available to address the difficulties these workers face, despite evidence that the lifetime earnings losses they experience are significant.

As explored in a recent Hamilton Project event, one option to address the needs of these workers is to facilitate training help develop new job-specific skills. Certain training programs, particularly those that bring together training providers and employers and industry groups, have proven successful in helping people get back to work. For workers who lost jobs that are not likely to come back, sizeable grants for longer-term training, along with the use of our nation’s network of One-Stop Career Centers, have been shown to have high returns.

As many Americans continue to face significant challenges in the labor market, The Hamilton Project will continue to explore their causes and the policy options in the year ahead.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Shrinking Job Opportunities: The Challenge of Putting Americans Back to Work

January 6, 2012