This chapter is part of USMCA Forward 2025, which focuses on areas where deepening cooperation between the United States, Mexico, and Canada can help advance key economic and national security goals.

As the world is coming to terms with the need to electrify to address the looming climate crisis, it is also coming to understand that electrification requires a significant quantity of minerals. This chapter focuses on a subset of critical minerals—those that are needed for the clean energy transition—also known as “energy transition minerals.” Energy transition minerals such as lithium, graphite, copper, nickel, rare earth elements, and cobalt are essential building blocks for a clean energy economy; they are used in wind turbines and solar panels, electric vehicle batteries, renewable energy transmission, and more.1 China dominates the energy transition minerals markets, and the U.S., Canada, and Mexico are all focused on securing their supply chains for these same minerals. This chapter examines opportunities for North America to become more self-sufficient in terms of energy transition mineral supply while also moving toward more responsibly sourced minerals.

The drivers for increased appetite for energy transition minerals

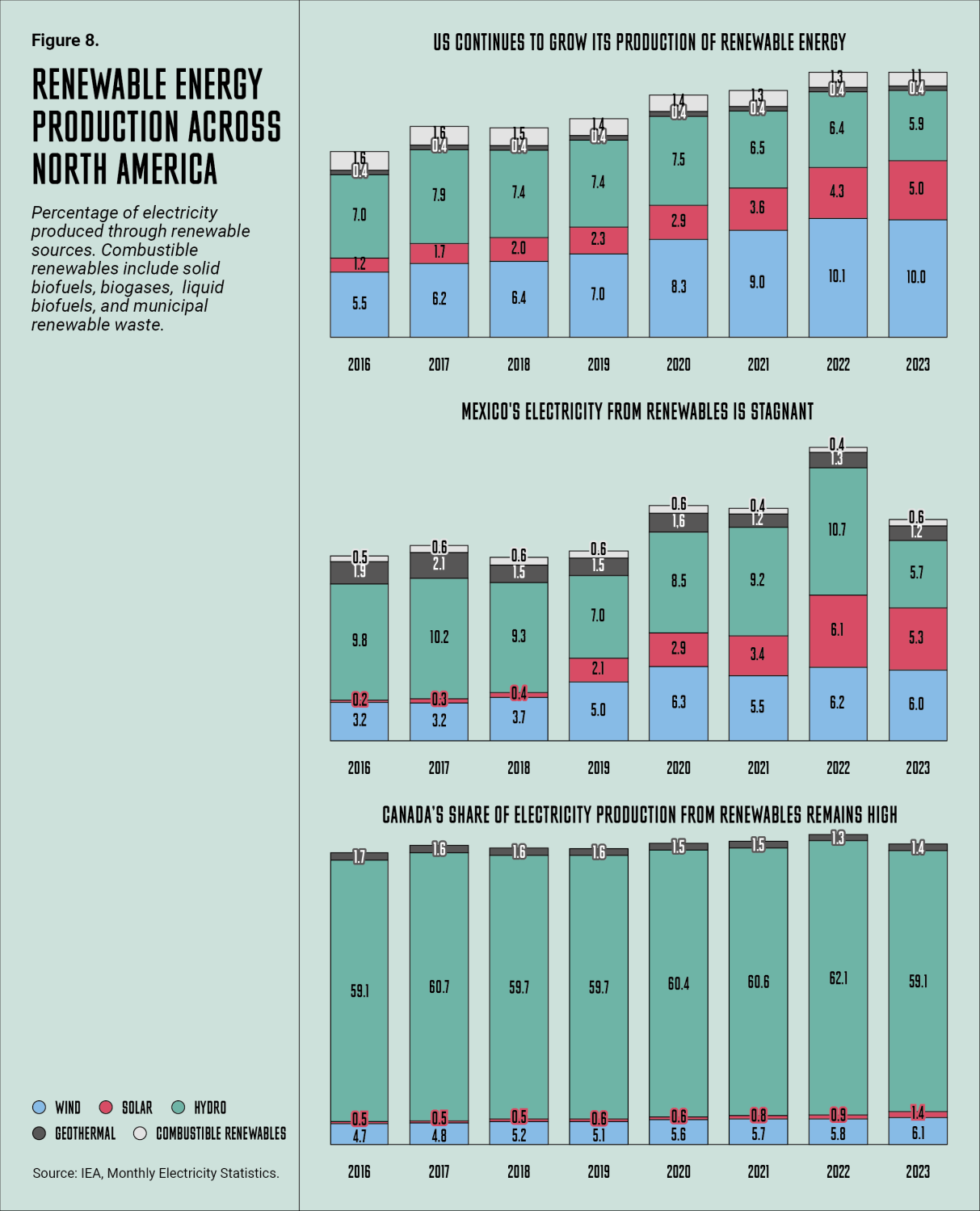

The U.S., Mexico, and Canada have each established decarbonization goals in their existing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). NDCs are documents submitted under the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that detail a country’s climate commitment over the next five years. In February 2025, an updated set of NDCs are due to be submitted. The U.S. released their new NDC in December 2024, with a target to reduce emissions by 61%-66% below 2005 levels by 2035. While the Trump administration has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, this target still serves as a guide for subnational action and could be adopted by a future U.S. president. Canada has yet to submit its new NDC, but did announce a new emissions reduction target of 45%-50% below 2005 levels by 2035. Mexico’s latest target is 35% reduction from a business-as-usual scenario by 2030. A successful and rapid energy transition is critical to meeting all three countries’ goals and will necessitate adding significant new renewable energy capacity and electric vehicle capacity, which will lead demand for transition minerals to double or even triple over the coming years.

Energy transition minerals sourcing within North America

At present, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico are neither mining nor processing significant quantities of any of the relevant critical minerals needed for decarbonization. Canada has a toehold in cobalt processing, as does the U.S. in rare earth extraction. While comparable data is not available for Canada or Mexico, according to the 2024 Mineral Commodity Summary by the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. is 100% net-import reliant for 16 critical minerals, including graphite, and more than 50% reliant on imports for another 29 critical minerals, including rare earths (>95%), zinc (77%), cobalt (67%), and nickel (57%). It is also reliant for the minerals that are used to make aluminum (>75% import reliant for bauxite and 59% reliant for alumina).

Over the past several years, the U.S. has initiated a broad effort to increase critical minerals mining and processing domestically through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,2 and the Trump administration appears committed to even stronger action to prioritize domestic mining and processing. Canada has made efforts to increase domestic mining, including investing to improve access for critical minerals projects and reform the permitting system for mining and other major projects. In 2022, Mexico’s domestic mining value was $3.3 billion. Mexico has an opportunity under President Claudia Sheinbaum to expand its mining sector by reopening to increased private investment in the sector.

North American trade in minerals is already important to all USMCA countries. The U.S. is the primary source of ore and metal imports to Canada and Mexico, at 56% and 65%, respectively. In fact, Canada imported more critical minerals from the U.S. than from other countries. In 2022, the U.S. exported $2.28 billion worth of minerals to Mexico—47% of Mexico’s mineral imports come from the United States. The U.S. was a dominant source for all Canadian and Mexican mineral imports and Mexico was a dominant source of graphite for Canada, but Canada was not a dominant source for Mexican imports. Fifty-two percent of Canada’s mineral exports went to the U.S. in 2022. Between 2019 and 2022, Canada was the United States’ primary import source for magnesium, nickel, tellurium, vanadium, and zinc–all listed critical minerals for which there is limited domestic mining in the U.S. In addition, during that same period, the U.S. imported about 20% of its refined copper from Canada. During the period from 2019-2022, Mexico was the United States’ primary import source for fluorspar and a significant import source for graphite and copper.

While Mexico has significant reserves of lithium, it faces challenges to integrating its resources with the U.S. and Canada. These impediments are due to organized crime and civil unrest. A ban by the former Lopez-Obrador administration on private lithium mining and processing activities also significantly curtailed investment. It is possible that President Sheinbaum will reverse this nationalist, anti-private sector approach.

China is another key exporter of critical minerals to North America. China supplied a greater number of nonfuel minerals to the U.S., 24 compared with 23 from Canada, and eight from Mexico. Data from 2014 shows that countries outside North America accounted for more than half of imports for the U.S., with Canada contributing 33% and Mexico only 10% of U.S. imports of critical minerals. North America’s share of global mining production has dropped from around 11% in 2016 to about 4% in 2023. Although it maintains about a 10% share of production of copper and rare earth elements specifically.

The opportunity to expand sources of energy transition minerals extraction in North America also requires a better understanding of their availability. The Critical Minerals Mapping Initiative (CMMI) is working to improve the knowledge base. The CMMI is a partnership between the geological surveys in the U.S., Canada, and Australia. As Mexico is not part of the CMMI, the U.S. and Canada ought to consider having Mexico join this partnership. Additionally, the U.S. began the Earth MRI program in 2019, focused on mapping the U.S. surface and subsurface, to Canada and Mexico.

The path to responsibly sourced minerals

Understanding the risks associated with mineral extraction

The extraction of critical minerals often causes significant negative impacts to both the environment and surrounding communities. Mining often has localized impacts (e.g., surface or groundwater pollution, air pollution, water consumption, waste management) and can also have global impacts (e.g., mercury pollution, greenhouse gas emissions) and system impacts (e.g., the sudden influx of mine workers contributing to social instability and increased crime rates).

Environmental challenges associated with mining value chain activities can negatively impact ecosystem services from which workers, communities, and regions derive benefit. One study estimates that the overall ecosystem services cost caused by mining four commodities globally—aluminum, copper, gold, and iron ore—is estimated at about $5.4 billion per year, with about two-thirds in forested areas. This has implications for livelihoods, health, well-being, and agency.

Social challenges associated with mining value chain activities writ large (i.e., not exclusive to energy transition minerals) include hazardous working conditions and labor abuses (e.g., child and forced labor, especially in artisanal and small-scale mining), displacement of local communities, disregard for land rights and Indigenous peoples’ rights, violations of the right to health, and threats to environmental defenders.3

Mining is also associated with challenges around the governance of the critical minerals value chain—from mining and processing to disposal and recycling. These challenges are not new, and the rapid increase in demand for critical minerals, along with the potential for significant economic gains to be realized in this push, makes the sector especially vulnerable to corruption risks. About 40% of the mineral production needed is expected to occur in countries with weak, poor, and failing resource governance.

While no country or its companies are immune from irresponsible operations and mining disasters at home and abroad, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico have relatively strong laws and regulations that support responsible mining. In the U.S., almost all new mines must be reviewed pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act and are subject to a network of strong environmental laws—including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act—which govern every aspect of a mine’s operation, require permits to be granted, and provide for state regulator oversight of operations. In Canada, there is a requirement to consult with and accommodate Indigenous groups.4 In Mexico, reforms to its mining laws in 2023 now allow concessions to be cancelled for ecological concerns, no longer allow concessions in natural protected areas, require free prior and informed consent from indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities, and establish permanent, nontransferable liability for waste generated through mining activities.5

In contrast, mining in China, the dominant source of transition minerals currently, has poor safety records and has caused significant domestic environmental degradation.

Demand-side management and circularity

North America cannot and should not rely solely on mining to avoid supply chain challenges; the U.S., Canada, and Mexico should focus on demand management and minerals circularity to minimize the need for the creation of new mining operations. Since primary minerals must be mined, the goal for sourcing is responsible mining. Secondary minerals, which are recycled, provide an opportunity to move beyond responsible sourcing to sustainable sourcing, meaning that minerals can be recovered at products’ end-of-life as inputs for another production cycle, rather than extracting virgin resources. Sometimes called “above-ground mines,” more recycling can minimize the need to develop new mines while also reducing solid and hazardous waste. According to the International Energy Agency’s global analysis, a successful scale-up of recycling can lower the need for new mining activity by 25%-40% by 2050.

Given the expected increase in electric vehicles (EVs) on the road, recycling capacity for EV batteries has been rapidly expanding. In 2023, the U.S. had over 100,000 tons of EV battery recycling capacity, with an additional 500,000 metric tons of capacity set to come online in the coming years. Canada is also making strides in EV battery recycling. Not only does it currently have six battery recycling plants, but some of North America’s biggest recycling companies, such as Lithion, are Canadian. While there has been Chinese company interest, and the Mexican government has evaluated developing EV battery recycling plants, there is a dearth of projects underway. Further, regional level battery recovery and recycling programs are expected to increase recycling rates.

Better recycling will require designing batteries for recyclability, more effective collection, developing high-standard recycling infrastructure, growing the domestic market for recycled content, and establishing enabling policies, regulations, and standards, including extended producer responsibility. The U.S., Canada, and Mexico should seek opportunities to develop regional recycling centers where feasible. Different collection protocols and facilities across North America are obstacles, from consumer electronics to EV batteries.

In addition to end-of-life products containing desirable minerals, mine wastes, and industry wastes also hold valuable stores of transition minerals. There are various efforts underway to obtain the necessary critical minerals without mining in greenfields, including recovery of rare earth elements from coal byproducts and from legacy and active mine wastes. As these early-stage projects are proven, they can not only provide important minerals, they can also serve as a driver to clean up orphaned and abandoned mines and create new revenue streams at operating mines.

The challenge of traceability

One significant challenge to ensuring that supplies of energy transition minerals are responsibly sourced within North America and other trusted countries is the ability to trace mineral products from their extraction site, through processing and refining, and as they are incorporated into final products such as EVs or photovoltaics that are imported into or built in North America.

Progress is being made on traceability: The EU Battery Regulation and IRA tax credits require supply chain tracing of critical minerals.

Voluntary assurance protocols including the Global Battery Alliance’s Battery Passport, as well as IRMA’s and Copper Mark’s Chain of Custody standards also support traceability. Blockchain technology is also being employed to support traceability. To further the development of traceability requirements, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico should build traceability requirements into their government procurement policies, and require supply chain tracing of critical minerals.

Voluntary assurance protocols including the Global Battery Alliance’s Battery Passport, as well as IRMA’s and Copper Mark’s chain of custody standards also support traceability. Blockchain technology is also being employed to support traceability. To further the development of traceability requirements, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico should build traceability requirements into their government procurement policies.

Regulations and voluntary standards

Various voluntary standards exist or are being developed to allow miners to show that they are operating responsibly.6 Voluntary approaches however need to be followed by mandatory standards in order to ensure that critical minerals are being extracted and refined consistent with preventing environmental degradation and addressing the social risks associated with mining—including providing local communities with a forum to have a voice in the process.

A range of efforts are also underway by governments and intergovernmental agencies to formalize responsible mining standards. These include the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) and the U.N. Secretary General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals. The MSP is a transnational association that aims to bolster global critical minerals supply. While this is a Biden administration initiative, President Trump has also committed to securing U.S. critical minerals supplies. The MSP comprises 15 members including the U.S. and Canada and in September 2024, the MSP Forum announced that Mexico would join. The work of the MSP Forum has two focal areas. First, it aims to develop projects that support and accelerate the implementation of sustainable critical minerals production. Second, the MSP Forum will host a policy dialogue that will identify policies for boosting sustainable production and local capacities, facilitate regulatory cooperation to foster fair competition, transparency, and predictability, and promote high environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards in critical mineral supply chains.

In September 2024, The U.N. Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals released a set of seven high-level voluntary principles to address challenges often linked to mining. These principles focus on human rights; environment and biodiversity; justice and equity; development (through benefit sharing, value addition, and economic diversification); fair investments, finance, and trade; good governance (through transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption measures); and multilateral and international cooperation. The Panel has also proposed establishing a high-level expert advisory group housed in the United Nations to accelerate greater benefit-sharing, value addition, and economic diversification in energy transition mineral value chains, as well as responsible and fair trade, investment, finance, and taxation. Other proposed initiatives focus on global traceability and transparency, mining legacy issues, and financial assurance, artisanal and small-scale mining, and implementation of material efficiency and circularity approaches.

While both the MSP and the U.N. effort hold significant promise, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico cannot wait for a complete set of protocols to emerge through either of these processes. Enforcement of existing laws in each country and enhancement of those laws as needed is the most valuable way to drive responsible production of energy transition minerals.

Where there are not sufficient strong, widespread, and well-enforced regulatory and legal regimes, high-bar voluntary schemes that implement credible assurance processes can be useful tools. The main voluntary initiatives used in North America that provide purchasers with information on performance are RMI, IRMA, the ICMM principles, Copper Mark, and Toward Sustainable Mining. While differences among these initiatives exist, they are increasingly comparable in terms of the underlying standards, and tools are available to compare them.

Using purchasing power to drive improved performance

The U.S., Mexico, and Canada could form a buyers’ club—setting minimum standards for responsible procurement. In doing so, they should engage the voices of non-buyer stakeholders, such as government regulators, civil society, and communities directly affected by mining activities. Decisions about what constitutes “good enough” standards should not be determined solely by the governments as buyers; rather, they should be decided with, or at least incorporate perspectives from, those impacted by mining. Decision-making processes should include carefully planned mechanisms to collect and incorporate these perspectives. Without this inclusive engagement, minimum standards could inadequately address local concerns and priorities, potentially undermining trust and leading to opposition or conflict.

Recommendations

As the U.S., Canada, and Mexico seek to shore up their supply chains of energy transition minerals:

- All three countries should take steps to encourage domestic mining and processing without loosening protections for the environment and nearby communities including Indigenous peoples. This can be done through a range of incentives such as the ones being offered in the U.S. via the IRA and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Canada through its Critical Minerals Strategy and Clean Technology Manufacturing investment tax credits.

- All three countries should encourage and favor investment from North American allies in mining and processing projects in country. Mexico, in particular, should reverse decisions by the past administration that were unfriendly to private investment in lithium mining and processing.

- The U.S. and Canada should include Mexico as a member of the Critical Minerals Mapping Initiative to support increased discoveries of valuable energy transition minerals.

Further, to ensure that their energy transition mineral supply chains are responsibly sourced, all three countries should take the following actions in order of priority:

- First, they should ensure that they are working on demand reduction by designing systems and products with lower demand for critical minerals (e.g., smaller batteries), and driving circularity in their minerals supply chains (e.g., reusing by extending the use life of products and components and recycling or bringing materials from waste streams back into the economy).

- Second, they should ensure that their domestic regulatory systems drive responsible sourcing from both an environmental and social perspective and they should look for opportunities to exploit domestic resources and to work collaboratively to support one another’s supply chains, including through increased efforts around primary processing and recycling. This could include the U.S., Canada, and Mexico working through existing schemes such as the MSP to agree to seek minerals that meet accepted ESG standards as a basis for sourcing critical minerals. The USMCA commitments on technical standards can ensure these standards become basis for domestic regulation.

- Third, they should establish a range of options to ensure that imports are responsibly sourced. This can include common approaches to tracing imports of critical minerals to understand their environmental and human rights impacts and restricting imports of critical minerals that fail to meet North American standards.

- Fourth, the U.S., Mexico, and Canada should use government procurement to drive standards for responsible sourcing of critical minerals, including requirement of traceability across the critical minerals supply chain. Under the USMCA Government Procurement chapter this could include giving suppliers from each country preferential access.

- Finally, they should look to voluntary assurance protocols to obtain minerals from projects that have provided assurance on their practices coupled with best-in-class tracing of the minerals from the mine site to the products being purchased in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

-

Footnotes

- It is worth noting that these clean energy products compete with other uses for minerals including aerospace, defense, high-tech manufacturing, consumer electronics, and medical devices.

- It has invested directly in projects at all stages of the minerals supply chain through Department of Energy Loans, IRA production tax credits, and by supporting a range of R&D efforts.

- The mining sector has consistently been the most dangerous sector for environmental human rights defenders with 495 documented allegations of human rights abuses between 2010 and 2021 associated with energy transition minerals. Mexico alone accounted for 47 of the documented attacks on defenders and was cited as the second most dangerous country. The U.S. and Canada together had 27 documented attacks on defenders. The mining industry is particularly at risk for human rights violations as operations are often located in remote areas and in regions marked by political instability, economic disparities, conflict, and weak governance.

- The requirement is encoded both in the Constitution Act, 1982 and through Canada’s framework for the Act (UNDRIP). UNDRIP includes commitments to free, prior, and informed consent and requires that the laws of Canada are consistent with this commitment.

- Reforms included amendments to the National Waters Law, the General Law of Ecological Equilibrium and Environmental Protection, and the General Law for the Prevention and Integral Handling of Wastes.

- This is another area of differentiation between North American and Chinese companies with North American companies applying standards at the site level and reporting against site-level compliance and Chinese companies applying these only at the corporate level. Further, North American companies’ voluntary standards focus on upstream performance to address technical requirements for responsible mining. The Chinese instruments are adopted mainly to reassure customers of good practices throughout complex supply chains.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).