On March 15, as the Russia-Ukraine war neared the three-week mark, Brookings experts held a discussion on developments in the conflict so far and what might be coming.

Steven Pifer (@steven_pifer)

Steven Pifer (@steven_pifer)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology and Center on the United States and Europe

President [Volodymyr] Zelenskyy, his government, but also the Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, continue to defiantly work in Kyiv, and they’re showing the determination that you’ve seen over the last two and a half weeks by the Ukrainians to resist the Russian attack. I think for many Ukrainians, this is almost an existential threat in that they see losing meaning an end to Ukrainian democracy and, particularly for younger people, meaning an end to the vision of Ukraine’s future as a normal European state. You have seen over the past week or so a couple of indications from President Zelenskyy of a readiness to be flexible. A couple of times he’s raised the question of neutrality and perhaps even suggested that Ukraine might alter its position with regards to NATO membership. But I don’t think he’s seen anything serious from Moscow unless something is taking place in discussions between Ukrainians and Russians that has not yet been disclosed. There also, though, is a sense of frustration, which is very clear in Kyiv that they really are fighting a war that they believe is not just against Ukraine, but perhaps is more broadly against Europe. They feel that they are fighting it alone. While they appreciate the arms supplies from the West, they do want to see something more, and they continue, for example, to repeat requests for a no-fly zone, which NATO has pretty much ruled out.

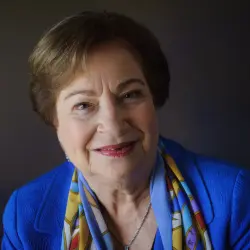

Angela Stent (@AngelaStent)

Angela Stent (@AngelaStent)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

We do have to ask how accurate is the information [Russian President Vladimir Putin is] getting? He apparently thought or was told by the people who are advising him that this operation would take about 72 hours, that Russian troops would march in, they would take Kyiv, the Ukrainians would welcome them as liberators, and they could accomplish regime change with a pro-Russian government that would eschew ties with the European Union, ties with NATO. That obviously didn’t happen. And I suppose it’s dawned on him and his closest advisers that there’s no easy capture of Kyiv, that Ukrainians are resisting as Steve Pifer has said quite valiantly, and that NATO was in fact being very restrained because President [Joe] Biden and Secretary General [Jens] Stoltenberg, have said, we are not going to get directly involved in a conflict with Russia. So one has to assume… that Russia’s war aims have changed, that the Kremlin realizes that probably regime change isn’t on the cards because if they were to put in power a puppet government, they’d have to occupy Ukraine with hundreds of thousands of troops. No puppet government could last when Russian troops withdrew. It’s not clear that they can take Kyiv, or that they think that they will. But on the other hand, they have been successful in terms of the southeastern part of Ukraine. One wonders whether they are going to be moving on Odesa at some point in the near future. They’ve leveled Mariupol, you’ve all seen the terrible scenes of destruction, the rubble in that city, the humanitarian catastrophe there. But they have taken territory and they have destroyed already much of Ukraine’s industrial base. So if they wanted to weaken Ukraine, they’ve clearly done that. If they wanted to endear themselves to the Ukrainians, they’ve done the exact opposite. I mean, everything that Putin and the Kremlin have done in the past year is to further alienate Ukrainians and to create a stronger sense of Ukrainian national identity.

James Goldgeier (@JimGoldgeier)

James Goldgeier (@JimGoldgeier)

Robert Bosch Senior Visiting Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

It’s clear that [Putin] doesn’t care about killing civilians. And so I think we can expect that to continue. And if it does, I think they’ll just be increasing pressure on NATO to do more. But at this point, if the goal is to send equipment to help Ukrainians defend themselves without having NATO member states have troops that are directly engaging with Russian forces, there are going to be limits to what NATO can do. It’s also important to note, NATO, the U.S., and its allies, have been very clear about defending every inch of NATO territory should Putin decide to escalate this war beyond Ukraine, and the reassurance of countries like Poland and the Baltics that NATO will be there to defend them is extremely important for NATO to do. Question is whether something occurs that’s sort of less than clear what it is, that does involve NATO’s territory, and then how NATO would respond. I think there are a lot of situations that could be quite murky that would put NATO in a very difficult position in terms of standing up for itself, defending itself, defending a member state, supporting Ukraine, but not getting into a war with Russia.

Célia Belin (@celiabelin)

Célia Belin (@celiabelin)

Visiting Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

I think what we’ve seen over the [last] few weeks is overwhelming unity coming out of Europe, not only at the EU level with European leaders all coming together, including those that were viewed as closer to Russia. An overwhelming unity in answering forcefully with very strong sanctions… The idea that this unity of purpose, this unity of action should continue not only during the moments of the conflict, but go forward in the future in achieving a greater sovereignty for Europe, greater independence from this toxic relationship with Russia… However, I am also mindful that what we are seeing in Europe is also quite of an emotional difference from what we can observe in the U.S. People who travel back and forth report that, you know, war feels much closer to home in Europe… It’s extremely close to home for Poland — Russia just attacked a military base in Ukraine two days ago that was only 11 miles from the Polish borders. But also because of the wave of almost three million refugees… There are scenes that are now happening on European territory that are unbearable to observe and even more given the proximity to home, including the destruction of private residential areas, people in basements. All the images that come out from the Ukraine war zone, the terrible situation of Mariupol residents, the flight of Jewish communities, flashbacks to the worst moments of European history. For all of these reasons, I believe we are still in a moment of high emotions that are represented by protests, by unity. But… because it’s so emotional, you will start to see a polarizing debate on what to do next. Because at the heart of the emotion is fear. And when you have fear, you start polarizing between those who are willing to tackle the threat and those who maybe want to do anything possible to avoid that the danger would get closer to home.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Russia’s ambitions, Ukraine’s resistance, and the West’s response

March 28, 2022